Identifying Barriers to Empowerment Initiatives in a Fire Service Command Structure: an International Comparison of the Issues of Empowerment in Four Fire Brigades

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Players Register A-Z 1895-2016

WAKEFIELD TRINITY RLFC PLAYERS REGISTER A-Z 1895-2016 HERITAGE NUMBERS … The Story Initial Ideas Our initial ideas for the heritage numbers came about a couple of years ago (approx. 2012), after seeing the success of Queensland in Australia, with Warrington being the first English club to follow suit. Next Step Tremendous work had been carried out by a group of rugby league historians in the 1970s (RL Record Keepers’ Club) who pooled their knowledge, and attempted to record every game in the first one hundred years of rugby league (1895-1994). Trinity’s were completed and fortunately we acquired the records to every Trinity game, and players, since 1895 The First 100 Years The teams for the first one hundred years of Trinity’s rugby league days (1895-1994) were recorded and each new player to make his debut noted. On the very first game there were fifteen (numbers 1-15) and each debutant after this was given the subsequent number, in position order (full back, winger, centre etc.). This was checked, double-checked and triple checked. By 1994 we had found 1,060 names. The Next 20 Years … Part 1 The next twenty years, to the modern day, were a little more difficult but we researched the Trinity playing records through the excellent ‘Rothman’s Year Books’ written by the late Raymond Fletcher and David Howes. These books started in 1981 and finished in 1999. Again, each debutant was given the next heritage number The Next 20 Years … Part 2 After the ‘Rothmans’ books ceased publication we used the yearbooks published by ‘League Weekly’, which also noted every new player, signed throughout the season. -

"Counterpoint"

MAY 25 and 26, 1968 Next Week's Fixtures MACQUARIE UNITED v. WARATAH-MAYFIELD WESTERN SUBURBS v. CESSNOCK SOUTH NEWCASTLE v. LAKES UNITED KURRI KURR! v. MAITLAND NORTHERN SUBURBS v. CENTRAL-CHARLESTOWN Now Showing- Charlton Heston, Maximilian Schell in "COUNTERPOINT" HUNTER STREET Technicolor (A) .f Phone: 2 1977 - Plus - COLOUR FEATURETTES Bookings at Theatre Sessions 11, 2, 5 and 8 Around the Clubs West First Grade captain-coach John Phillip Radford didn't take long to Hobby had an outstanding game against hit top form after a cartilege operation. Macquarie. This player showed that he "Raddish" will put plenty of pressure is still one of the best footballers to on our First Graders in the Lakes for play in the Newcastle area since the war. wards to keep him out. Good on you John, keep it up with another such game against Waratah All at Lakes are upset over Brahma's today. omission from the World Cup side. This last slap in the face to Newcastle's two Allan's must surely be the worst treat Kurri Injured Players Lncky No., ment ever handed out to sportsmen in Kurri v Cessnock was won by Mr. our area. Skinner, Edward Street, Kurri. To Noel McNamara and Warren Small playing their initial 1st Grade To our Senior Vice-President's wife, match with Lakes, go all our best wish Mrs. George Johns, a speedy recovery. es. Both, only youngsters, have a big future in Rugby League. A correction for last week's pro gramme; it was South Newcastle Congratulations to Cessnock captain Leagues Club that so generously gave ·Brian Slade, and his good wife Sue, on the two nights entertainment for three the birth of a baby girl. -

P1 2/7/10 08:46 Page 1

p1 2/7/10 08:46 Page 1 2010 p2 1/7/10 15:26 Page 1 What does the Carnegie Challenge Cup mean to you? CARNEGIE CHALLENGE CUP FINAL Saturday 28th August, kick off 2.30pm, Wembley TICKETS £21 - £76. SPECIAL FAMILY TICKET OFFER*: £55 & £79 BOOK NOW, Call 0844 856 1113 or visit www.rugbyleaguetickets.co.uk For Hospitality call 0844 856 1114. For Disabled enquiries call 0844 856 1113 or e-mail [email protected] *2 adults & 2 children. Offer on £21 & £31 tickets p3 1/7/10 15:27 Page 1 Welcome to the Carnegie Champion Schools Finals ON behalf of the RFL, I would like to welcome you all to the finals of the 2010 Carnegie Champion Schools. The tournament has enjoyed another successful year and the competition which is open to all High Schools across Great Britain remains the largest Rugby League knock-out competition in the world. The Carnegie Champion Schools tournament is a great way to introduce young people to Rugby League and creates exciting opportunities for them to play alongside their school friends and enjoy a fantastically beneficial sporting experience. We have seen in previous years that many players involved in these finals have gone on to have very successful careers within the sport and some have even reached a professional playing level. In recent years, Sam Tomkins, Joe have been a part of the Carnegie Champion Westerman and Richie Myler have all Schools in 2010. The tournament would not featured in the Carnegie Champion Schools be such a success without your input and Tournament and gone on to forge high dedication. -

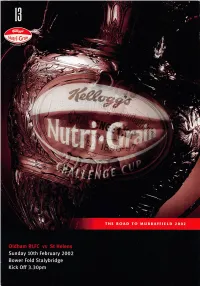

Sunday 10Th February 2002 Bower Fold Stalybridge Kick Off 3.30Pm OLDHAM

I .\ V. THE ROAD TO MURRAYFIELD 2002 O l d h a m R L F C v s S t H e l e n s Sunday 10th February 2002 Bower Fold Stalybridge Kick Off 3.30pm OLDHAM at the very heart of the North kJest Oldham continues to take significant strides to be THE desirable place to live, work or visit at the heart of the North West. Massive investment in regeneration and renewal continues apace and Oldham has the region's largest town centre based indoor shopping area. Businesses are benefiting from the new M60 motorway which now puts Oldham less than 25 minutes away from Manchester Airport. Anew bus station and the anticipation of the Metrolink tram system coming to Oldham soon further strengthen the appeal of the town for investment and new opportunities. Add to this superb opportunities for education and training, including anew Business Management School, exciting developments in tourism and the arts like the newly opened Huddersfield Narrow Canal and the soon-to-be opened Art Gallery and the desirability of Oldham becomes even clearer. Enquiries to the Marketing and Communications Unit, PO Box 160, Civic Centre, West Street, Oldham, OL1 1UG. Telephone 0161 911 4707, Fax 0161 911 4936. E-mail [email protected], or visit our website at www.oldham.gov.uk Oldham Rugby League Football HotSeat Club (1997) Limited 64 Union Street O l d h a m 0 L 1 1 D J with Telephone: 0161 628 3677 Fax: 0161 627 5700 Christopher Hamiiton Club Shop: 0161 627 2141 CHAIRMAN WELCOME to our latest ‘Home’ Stalybridge Celtic. -

Heritage Numbers

WAKEFIELD TRINITY RLFC HERITAGE NUMBERS 1895-2016 HERITAGE NUMBERS … The Story Initial Ideas Our initial ideas for the heritage numbers came about a couple of years ago (approx. 2012), after seeing the success of Queensland in Australia, with Warrington being the first English club to follow suit. Next Step Tremendous work had been carried out by a group of rugby league historians in the 1970s (RL Record Keepers’ Club) who pooled their knowledge, and attempted to record every game in the first one hundred years of rugby league (1895-1994). Trinity’s were completed and fortunately we acquired the records to every Trinity game, and players, since 1895 The First 100 Years The teams for the first one hundred years of Trinity’s rugby league days (1895-1994) were recorded and each new player to make his debut noted. On the very first game there were fifteen (numbers 1-15) and each debutant after this was given the subsequent number, in position order (full back, winger, centre etc.). This was checked, double-checked and triple checked. By 1994 we had found 1,060 names. The Next 20 Years … Part 1 The next twenty years, to the modern day, were a little more difficult but we researched the Trinity playing records through the excellent ‘Rothman’s Year Books’ written by the late Raymond Fletcher and David Howes. These books started in 1981 and finished in 1999. Again, each debutant was given the next heritage number The Next 20 Years … Part 2 After the ‘Rothmans’ books ceased publication we used the yearbooks published by ‘League Express’, which also noted every new player, signed throughout the season.