ACPA Guide to Pain Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Associations of Regular Glucosamine Use with All-Cause and Cause

Epidemiology Ann Rheum Dis: first published as 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217176 on 6 April 2020. Downloaded from EPIDEMIOLOGICAL SCIENCE Associations of regular glucosamine use with all- cause and cause- specific mortality: a large prospective cohort study Zhi- Hao Li,1 Xiang Gao,2 Vincent CH Chung,3 Wen- Fang Zhong,1 Qi Fu,3 Yue- Bin Lv,4 Zheng- He Wang,1 Dong Shen,1 Xi- Ru Zhang,1 Pei-Dong Zhang,1 Fu- Rong Li,1 Qing- Mei Huang,1 Qing Chen,1 Wei- Qi Song,1 Xian- Bo Wu,1 Xiao-Ming Shi,4 Virginia Byers Kraus,5 Xingfen Yang,6 Chen Mao 1 Handling editor Josef S ABSTRact Key messages Smolen Objectives To evaluate the associations of regular glucosamine use with all-cause and cause-specific ► Additional material is What is already known about this subject? published online only. To view mortality in a large prospective cohort. ► Although several epidemiological investigations please visit the journal online Methods This population- based prospective cohort indicated that glucosamine use might play a (http:// dx. doi. org/ 10. 1136/ study included 495 077 women and men (mean (SD) role in prevention of cancer, cardiovascular annrheumdis- 2020- 217176). age, 56.6 (8.1) years) from the UK Biobank study. disease (CVD), and other diseases, only a Participants were recruited from 2006 to 2010 and For numbered affiliations see few studies have evaluated the associations were followed up through 2018. We evaluated all-cause end of article. between glucosamine use and mortality mortality and mortality due to cardiovascular disease outcomes, especially for cause- specific Correspondence to (CVD), cancer, respiratory and digestive disease. -

Could Mycolactone Inspire New Potent Analgesics? Perspectives and Pitfalls

toxins Review Could Mycolactone Inspire New Potent Analgesics? Perspectives and Pitfalls 1 2 3, 4, , Marie-Line Reynaert , Denis Dupoiron , Edouard Yeramian y, Laurent Marsollier * y and 1, , Priscille Brodin * y 1 France Univ. Lille, CNRS, Inserm, CHU Lille, Institut Pasteur de Lille, U1019-UMR8204-CIIL-Center for Infection and Immunity of Lille, F-59000 Lille, France 2 Institut de Cancérologie de l’Ouest Paul Papin, 15 rue André Boquel-49055 Angers, France 3 Unité de Microbiologie Structurale, Institut Pasteur, CNRS, Univ. Paris, F-75015 Paris, France 4 Equipe ATIP AVENIR, CRCINA, INSERM, Univ. Nantes, Univ. Angers, 4 rue Larrey, F-49933 Angers, France * Correspondence: [email protected] (L.M.); [email protected] (P.B.) These three authors contribute equally to this work. y Received: 29 June 2019; Accepted: 3 September 2019; Published: 4 September 2019 Abstract: Pain currently represents the most common symptom for which medical attention is sought by patients. The available treatments have limited effectiveness and significant side-effects. In addition, most often, the duration of analgesia is short. Today, the handling of pain remains a major challenge. One promising alternative for the discovery of novel potent analgesics is to take inspiration from Mother Nature; in this context, the detailed investigation of the intriguing analgesia implemented in Buruli ulcer, an infectious disease caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium ulcerans and characterized by painless ulcerative lesions, seems particularly promising. More precisely, in this disease, the painless skin ulcers are caused by mycolactone, a polyketide lactone exotoxin. In fact, mycolactone exerts a wide range of effects on the host, besides being responsible for analgesia, as it has been shown notably to modulate the immune response or to provoke apoptosis. -

Osteoarthritis (OA) Is a Pain

R OBE 201 CT 1 O Managing Osteoarthritis With Nutritional Supplements Containing Glucosamine, Chondroitin Sulfate, and Avocado/Soybean Unsaponifiables steoarthritis (OA) is a pain- successfully recommending OJHSs treatment algorithm exists for man- ful, progressive degeneration containing a combination of glu- aging patients with OA, acetamin- O of the joint characterized by cosamine, chondroitin sulfate (CS), ophen is a first-line drug recom- progressive cartilage loss, subchon- and avocado/soybean unsaponifi- mended to help control pain and dral bone remodeling, formation of ables (ASU) for the management increase mobility. Acetaminophen periarticular osteophytes, and mild of OA. It will briefly review the is associated with both hepatic and to moderate synovitis accompanied available pharmacokinetics/phar- renal damage, particularly in patients by an increase in pro-inflammatory macodynamics and safety profile who exceed the recommended daily cytokines, chemokines, and a vari- of OJHSs containing a mixture of dose or use it in combination with ety of inflammatory mediators.1 glucosamine, CS, and ASU, outline moderate amounts of alcohol. 6 There is no cure for OA; therefore, strategies to identify appropriate Worsening pain, disease progression, once an individual is diagnosed, patients for OJHSs containing these and inefficacy of acetaminophen managing OA becomes a lifelong ingredients, and provide web-based often necessitate initiating prescrip- process. Although a physician ini- resources (TABLE 1) that will assist tion NSAIDs (such as COX-2 tially diagnoses OA, pharmacists are pharmacists in educating and coun- inhibitors), which carry the risk of the most accessible health care pro- seling patients. gastrointestinal effects (e.g., gas- fessional and play an integral role tropathy), renal toxicities, and seri- in managing each patient’s joint CURRENT RECOMMENDATIONS ous cardiovascular events. -

Ketamine: an Update for Its Use in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome

xperim & E en l ta a l ic P in h Bentley et al., Clin Exp Pharmacol 2015, 5:2 l a C r m f Journal of DOI: 10.4172/2161-1459.1000169 o a l c a o n l o r g u y o J ISSN: 2161-1459 Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology Commentry Open Access Ketamine: An Update for Its Use in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome and Major Depressive Disorder William E Bentley*, Michael Sabia, Michael E Goldberg and Irving W Wainer Cooper University Hospital, Camden, New Jersey, United States of America Abstract In recent years, there has been significant research in regard to the efficacy of ketamine in regards to treating Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) and Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). Many patients have had substantial symptomatic relief; however, not all patients have had positive results. This has prompted current research with evidence to suggest certain biomarkers exist that would infer which patients will/will not respond to ketamine treatment. Current biomarkers of interest include D-Serine (D-Ser) and magnesium, which will be discussed. Whether or not D-Ser and/or magnesium levels should be checked and possibly dictate therapy is an area of future research. It is also possible that downstream metabolites of ketamine are the key to successful therapy. Keywords: Complex regional pain syndrome; Major Depressive thoughts; and slowing of speech and action. These changes must last a Disorder(MDD); Ketamine minimum of 2 weeks and interfere considerably with work and family relations” [6]. Treatment options include antidepressant medications, Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) and Major Depressive cognitive behavioral therapy, and interpersonal therapy. -

Identification of Glucosamine Hydrochloride Diclofenac Sodium Interaction Products by Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry

Available online www.jocpr.com Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Research, 2014, 6(5):761-767 ISSN : 0975-7384 Research Article CODEN(USA) : JCPRC5 Identification of glucosamine hydrochloride diclofenac sodium interaction products by chromatography-mass spectrometry А. А. Sichkar Industrial Pharmacy Department, National University of Pharmacy, Kharkiv, Ukraine _____________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT Researches of chemical transformation products of diclofenac sodium and glucosamine hydrochloride at their joint presence have been carried out by means of the gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Mechanical mixes of substances were investigated before and after technological operations of humidifying and drying. It has been proven that one medicinal substance influences another. The formation of several reaction products during the chemical interaction between diclofenac sodium and glucosamine hydrochloride has been shown. Key words: diclofenac sodium, glucosamine hydrochloride, chemical transformation products, gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. _____________________________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION Diclofenac sodium is in the first line of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) for the pain relief and reduction of an inflammatory process activity in most diseases of connective tissue and joints over decades. However, along with pronounced therapeutic effect the use of this NSAID is associated with several side effects, including lesions of the gastrointestinal tract and inhibition of the metabolism of articular cartilage [1, 2, 3, 4]. Creation of new combined drugs with NSAIDs and other medicinal substances is one of the major direction of NSAIDs pharmacological properties spectrum spread and reduce their toxicity [5, 6, 7, 8]. Thus, in the National University of Pharmacy at the Department of Clinical Pharmacology and Clinical Pharmacy under the supervision of prof. Zupanets I.A. -

Treatment on Gouty Arthritis Animal Model

Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science Vol. 7 (07), pp. 202-207, July, 2017 Available online at http://www.japsonline.com DOI: 10.7324/JAPS.2017.70729 ISSN 2231-3354 Anti-inflammatory and anti-hyperuricemia properties of chicken feet cartilage: treatment on gouty arthritis animal model Tri Dewanti Widyaningsih*, Widya Dwi Rukmi Putri, Erni Sofia Murtini, Nia Rochmawati, Debora Nangin Department of Agricultural Product Technology, Faculty of Agricultural Technology, Brawijaya University, Malang 65145, Indonesia. ABSTRACT ARTICLE INFO Article history: Gout is a form of inflammatory arthritis caused by the deposition of uric acid. The therapeutic approach to gout Received on: 22/03/2017 is mainly divided by the treatment of inflammation and the management of serum urate level. This study aim to Accepted on: 13/05/2017 investigate whether chondroitin sulfate (CS) and glucosamine in chicken feet cartilage powder (CFE) and Available online: 30/07/2017 aqueous extract (AE) are able to decrease serum urate level and inflammation in animal model of gouty arthritis. CFE and AE were evaluated in vitro for xanthine oxidase (XO) inhibition. The anti-hyperuricemic activity and Key words: liver XO inhibition were evaluated in vivo on oxonate-induced hyperuricemia rats. Anti-inflammatory property Chicken feet cartilage, gout, was also determined on monosodium urate (MSU) crystal-induced paw edema model. CFE and AE hyperuricemia, monosodium supplementation showed urate-lowering activity. However, both treatments were not able to inhibit in vitro and urate, inflammation. in vivo XO activity. In MSU crystal-induced mice, the levels of paw swelling and lipid peroxidation were increased; in addition, a decrease in the activities of SOD and changes in the expression of CD11b+TNF-α and CD11b+IL-6 of the spleen were demonstrated. -

Membrane Stabilizer Medications in the Treatment of Chronic Neuropathic Pain: a Comprehensive Review

Current Pain and Headache Reports (2019) 23: 37 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-019-0774-0 OTHER PAIN (A KAYE AND N VADIVELU, SECTION EDITORS) Membrane Stabilizer Medications in the Treatment of Chronic Neuropathic Pain: a Comprehensive Review Omar Viswanath1,2,3 & Ivan Urits4 & Mark R. Jones4 & Jacqueline M. Peck5 & Justin Kochanski6 & Morgan Hasegawa6 & Best Anyama7 & Alan D. Kaye7 Published online: 1 May 2019 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Purpose of Review Neuropathic pain is often debilitating, severely limiting the daily lives of patients who are affected. Typically, neuropathic pain is difficult to manage and, as a result, leads to progression into a chronic condition that is, in many instances, refractory to medical management. Recent Findings Gabapentinoids, belonging to the calcium channel blocking class of drugs, have shown good efficacy in the management of chronic pain and are thus commonly utilized as first-line therapy. Various sodium channel blocking drugs, belonging to the categories of anticonvulsants and local anesthetics, have demonstrated varying degrees of efficacy in the in the treatment of neurogenic pain. Summary Though there is limited medical literature as to efficacy of any one drug, individualized multimodal therapy can provide significant analgesia to patients with chronic neuropathic pain. Keywords Neuropathic pain . Chronic pain . Ion Channel blockers . Anticonvulsants . Membrane stabilizers Introduction Neuropathic pain, which is a result of nervous system injury or lives of patients who are affected. Frequently, it is difficult to dysfunction, is often debilitating, severely limiting the daily manage and as a result leads to the progression of a chronic condition that is, in many instances, refractory to medical This article is part of the Topical Collection on Other Pain management. -

Intrathecal Drug Infusions

INTRATHECAL DRUG INFUSIONS RATIONAL USE OF POLYANALGESIA TIMOTHY R. DEER, MD • PRESIDENT AND CEO, THE CENTER FOR PAIN RELIEF, CHARLESTON, WEST VIRGINIA • CLINICAL PROFESSOR OF ANESTHESIOLOGY, WEST VIRGINIA UNIVERSITY • BOARD OF DIRECTORS, INTERNATIONAL NEUROMODULATION SOCIETY • IMMEDIATE PAST CHAIR, AMERICAN SOCIETY OF ANESTHESIOLOGISTS, COMMITTEE ON PAIN MEDICINE • BOARD OF DIRECTORS; AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PAIN MEDICINE AND AMERICAN SOCIETY OF INTERVENTIONAL PAIN PHYSICIANS 2 INS 2009 • SYMPOSIUM ON INTRATHECAL DRUG DELIVERY • DISCLOSURES IN INTRATHECAL DRUG DELIVERY • CONSULTANT: INSET, JOHNSON AND JOHNSON. Intrathecal Pump for Pain ! 1 mg intrathecal morphine = 300 mg oral morphine CONFIDENTIAL Krames ES. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1996 Jun;11(6):333-52 4 Objectives • Review current options for pump infusions • Build on the talks of Dr. Levy and Dr. Abejon • Use a case based approach to discuss the issues • Make conclusions regarding the algorithm of Intrathecal analgesia Clinical Decision Making • Regulatory Approval in your country • Case reports • Lectures and anecdotal information • Retrospective analysis • Double-blind, randomized, prospective studies • Physician innovation with no available evidence • Consensus Statements 2000 Guidelines for Intraspinal Infusion 2007 Polyanalgesic Consensus Guidelines for Management of Pain by Intraspinal Drug Delivery Line 1 Morphine or Hydromorphone or Ziconotide Fentanyl or Clonodine alone OR one of the following 2-drug Line 2 combinations: • Morphine (or Hydromorphone) + Ziconotide • Morphine (or -

Methyl Salicylate, Menthol, Camphor Cream Semprae

FLEXILON- methyl salicylate, menthol, camphor cream Semprae Laboratories Inc Disclaimer: Most OTC drugs are not reviewed and approved by FDA, however they may be marketed if they comply with applicable regulations and policies. FDA has not evaluated whether this product complies. ---------- ACTIVE INGREDIENT Camphor 4% Menthol 7.5% Methyl Salicylate 10% PURPOSE Topical analgesic USES For the temporary relief of minor aches and pains of muscles and joints associated with: simple backache arthritis strains bruises sprains WARNINGS For external use only Do not use on wounds or damaged , broken or irritated skin with a heating pad When using this product avoid contact with eyes or mucous membranes do not bandage tightly Stop use and ask a doctor if condition worsens you have redness over the affected area symptoms persist for more than 7 days or symptoms clear up and occur within a few days excessive skin irritation occurs Keep out of reach of children If swallowed, get medical help or contact a Poison Center immediately DIRECTIONS use only as directed Adults and children 12 years of age and older: Apply to affected area not more than 3 to 4 times daily. Children under 12 years of age: consult a doctor. OTHER INFORMATION store at 20-25C (68-77F) Do not purchase if outer seal is broken INACTIVE INGREDIENTS carbomer, cetearyl alcohol, D.I. water, FD&C Blue no. 1, FD&C Yellow no.5, glucosamine sulfate, glyceryl monostearate, methyl sulfonyl methane, methylparaben, mineral oil 90, PEG-100, propylparaben, polysorbate 60, stearyl alcohol, triethanolamine -

Dietary Supplements for Osteoarthritis Philip J

Dietary Supplements for Osteoarthritis PHILIP J. GREGORY, PharmD; MORGAN SPERRY, PharmD; and AmY FRIEdmAN WILSON, PharmD Creighton University School of Pharmacy and Health Professions, Omaha, Nebraska A large number of dietary supplements are promoted to patients with osteoarthritis and as many as one third of those patients have used a supplement to treat their condition. Glucosamine-containing supplements are among the most commonly used products for osteo- arthritis. Although the evidence is not entirely consistent, most research suggests that glucos- amine sulfate can improve symptoms of pain related to osteoarthritis, as well as slow disease progression in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Chondroitin sulfate also appears to reduce osteoarthritis symptoms and is often combined with glucosamine, but there is no reliable evi- dence that the combination is more effective than either agent alone. S-adenosylmethionine may reduce pain but high costs and product quality issues limit its use. Several other supplements are promoted for treating osteoarthritis, such as methylsulfonylmethane, Harpagophytum pro- cumbens (devil’s claw), Curcuma longa (turmeric), and Zingiber officinale (ginger), but there is insufficient reliable evidence regarding long-term safety or effectiveness. Am( Fam Physician. 2008;77(2):177-184. Copyright © 2008 American Academy of Family Physicians.) ietary supplements, commonly glycosaminoglycans, which are found in referred to as natural medicines, synovial fluid, ligaments, and other joint herbal medicines, or alternative structures. Exogenous glucosamine is derived medicines, account for nearly from marine exoskeletons or produced syn- D $20 billion in U.S. sales annually.1 These thetically. Exogenous glucosamine may have products have a unique regulatory status that anti-inflammatory effects and is thought to allows them to be marketed with little or no stimulate metabolism of chondrocytes.4 credible scientific research. -

Chondroitin/Glucosamine Equal to Celecoxib for Knee Osteoarthritis

POEMs and function. The patients were randomized POEMs (patient-oriented evidence that matters) are provided by Essential Evidence Plus, a point-of-care clinical decision support system published by Wiley- (concealed allocation unknown) to receive Blackwell. For more information, see http://www.essentialevidenceplus.com. 400-mg chondroitin sulfate/500-mg glucos- Copyright Wiley-Blackwell. Used with permission. amine hydrochloride three times a day or For definitions of levels of evidence used in POEMs, see http://www. 200-mg celecoxib every day for six months essentialevidenceplus.com/product/ebm_loe.cfm?show=oxford. (both with matched placebo). The glucos- To subscribe to a free podcast of these and other POEMs that appear in AFP, amine/chondroitin dose is a little higher search in iTunes for “POEM of the Week” or go to http://goo.gl/3niWXb. than is typically recommended and studied. At six months, using a modified intention- This series is coordinated by Sumi Sexton, MD, Associate Deputy Editor. to-treat analysis that included only 94% of A collection of POEMs published in AFP is available at http://www.aafp.org/afp/ enrolled patients, WOMAC pain scores were poems. decreased by 50% in both groups, stiffness scores decreased 46.9% with the combination vs. 49.2% with celecoxib (P = not significant), Chondroitin/Glucosamine Equal and function improved similarly (decreased to Celecoxib for Knee Osteoarthritis in 45.5% vs. 46.4%; P = not significant). Clinical Question Study design: Randomized controlled trial (double-blinded) Is combined chondroitin/glucosamine as effective as celecoxib (Celebrex) in reducing Funding source: Industry pain and improving function in patients with Allocation: Uncertain painful knee osteoarthritis? Setting: Outpatient (specialty) Reference: Hochberg MC, Martel-Pelletier J, Bottom Line Monfort J, et al.; MOVES Investigation Group. -

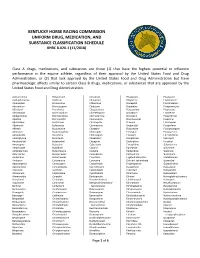

Drug and Medication Classification Schedule

KENTUCKY HORSE RACING COMMISSION UNIFORM DRUG, MEDICATION, AND SUBSTANCE CLASSIFICATION SCHEDULE KHRC 8-020-1 (11/2018) Class A drugs, medications, and substances are those (1) that have the highest potential to influence performance in the equine athlete, regardless of their approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration, or (2) that lack approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration but have pharmacologic effects similar to certain Class B drugs, medications, or substances that are approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. Acecarbromal Bolasterone Cimaterol Divalproex Fluanisone Acetophenazine Boldione Citalopram Dixyrazine Fludiazepam Adinazolam Brimondine Cllibucaine Donepezil Flunitrazepam Alcuronium Bromazepam Clobazam Dopamine Fluopromazine Alfentanil Bromfenac Clocapramine Doxacurium Fluoresone Almotriptan Bromisovalum Clomethiazole Doxapram Fluoxetine Alphaprodine Bromocriptine Clomipramine Doxazosin Flupenthixol Alpidem Bromperidol Clonazepam Doxefazepam Flupirtine Alprazolam Brotizolam Clorazepate Doxepin Flurazepam Alprenolol Bufexamac Clormecaine Droperidol Fluspirilene Althesin Bupivacaine Clostebol Duloxetine Flutoprazepam Aminorex Buprenorphine Clothiapine Eletriptan Fluvoxamine Amisulpride Buspirone Clotiazepam Enalapril Formebolone Amitriptyline Bupropion Cloxazolam Enciprazine Fosinopril Amobarbital Butabartital Clozapine Endorphins Furzabol Amoxapine Butacaine Cobratoxin Enkephalins Galantamine Amperozide Butalbital Cocaine Ephedrine Gallamine Amphetamine Butanilicaine Codeine