How New Yorkers' Obsession with Cuba Gave Rise to Salsa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Mambo on 2: the Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City

Centro Journal ISSN: 1538-6279 [email protected] The City University of New York Estados Unidos Hutchinson, Sydney Mambo On 2: The Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City Centro Journal, vol. XVI, núm. 2, fall, 2004, pp. 108-137 The City University of New York New York, Estados Unidos Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=37716209 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Hutchinson(v10).qxd 3/1/05 7:27 AM Page 108 CENTRO Journal Volume7 xv1 Number 2 fall 2004 Mambo On 2: The Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City SYDNEY HUTCHINSON ABSTRACT As Nuyorican musicians were laboring to develop the unique sounds of New York mambo and salsa, Nuyorican dancers were working just as hard to create a new form of dance. This dance, now known as “on 2” mambo, or salsa, for its relationship to the clave, is the first uniquely North American form of vernacular Latino dance on the East Coast. This paper traces the New York mambo’s develop- ment from its beginnings at the Palladium Ballroom through the salsa and hustle years and up to the present time. The current period is characterized by increasing growth, commercialization, codification, and a blending with other modern, urban dance genres such as hip-hop. [Key words: salsa, mambo, hustle, New York, Palladium, music, dance] [ 109 ] Hutchinson(v10).qxd 3/1/05 7:27 AM Page 110 While stepping on count one, two, or three may seem at first glance to be an unimportant detail, to New York dancers it makes a world of difference. -

The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBORAH F. RUTTER , President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 4, 2016, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters GARY BURTON WENDY OXENHORN PHAROAH SANDERS ARCHIE SHEPP Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center’s Artistic Director for Jazz. WPFW 89.3 FM is a media partner of Kennedy Center Jazz. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 2 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, pianist and Kennedy Center artistic director for jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, chairman of the NEA DEBORAH F. RUTTER, president of the Kennedy Center THE 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS Performances by NEA JAZZ MASTERS: CHICK COREA, piano JIMMY HEATH, saxophone RANDY WESTON, piano SPECIAL GUESTS AMBROSE AKINMUSIRE, trumpeter LAKECIA BENJAMIN, saxophonist BILLY HARPER, saxophonist STEFON HARRIS, vibraphonist JUSTIN KAUFLIN, pianist RUDRESH MAHANTHAPPA, saxophonist PEDRITO MARTINEZ, percussionist JASON MORAN, pianist DAVID MURRAY, saxophonist LINDA OH, bassist KARRIEM RIGGINS, drummer and DJ ROSWELL RUDD, trombonist CATHERINE RUSSELL, vocalist 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS -

The 2018 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2018 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 10:33 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBoRAh F. RUTTER, President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 16, 2018, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2018 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2018 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters TODD BARKAN JOANNE BRACKEEN PAT METHENY DIANNE REEVES Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz. This performance will be livestreamed online, and will be broadcast on Sirius XM Satellite Radio and WPFW 89.3 FM. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 10:33 AM Page 2 THE 2018 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, Chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts DEBORAH F. RUTTER, President of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts The 2018 NEA JAzz MASTERS Performances by NEA Jazz Master Eddie Palmieri and the Eddie Palmieri Sextet John Benitez Camilo Molina-Gaetán Jonathan Powell Ivan Renta Vicente “Little Johnny” Rivero Terri Lyne Carrington Nir Felder Sullivan Fortner James Francies Pasquale Grasso Gilad Hekselman Angélique Kidjo Christian McBride Camila Meza Cécile McLorin Salvant Antonio Sanchez Helen Sung Dan Wilson 4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 -

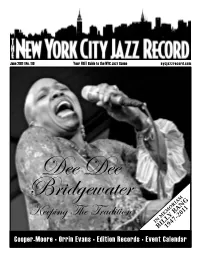

Keeping the Tradition Y B 2 7- in MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar

June 2011 | No. 110 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Dee Dee Bridgewater RIAM ANG1 01 Keeping The Tradition Y B 2 7- IN MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar It’s always a fascinating process choosing coverage each month. We’d like to think that in a highly partisan modern world, we actually live up to the credo: “We New York@Night Report, You Decide”. No segment of jazz or improvised music or avant garde or 4 whatever you call it is overlooked, since only as a full quilt can we keep out the cold of commercialism. Interview: Cooper-Moore Sometimes it is more difficult, especially during the bleak winter months, to 6 by Kurt Gottschalk put together a good mixture of feature subjects but we quickly forget about that when June rolls around. It’s an embarrassment of riches, really, this first month of Artist Feature: Orrin Evans summer. Just like everyone pulls out shorts and skirts and sandals and flipflops, 7 by Terrell Holmes the city unleashes concert after concert, festival after festival. This month we have the Vision Fest; a mini-iteration of the Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT); the On The Cover: Dee Dee Bridgewater inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival taking place at the titular club as well as other 9 by Marcia Hillman city venues; the always-overwhelming Undead Jazz Festival, this year expanded to four days, two boroughs and ten venues and the 4th annual Red Hook Jazz Encore: Lest We Forget: Festival in sight of the Statue of Liberty. -

Myspace.Com - - 43 - Male - PHILAD

MySpace.com - WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM - 43 - Male - PHILAD... http://www.myspace.com/recordcastle Sponsored Links Gear Ink JazznBlues Tees Largest selection of jazz and blues t-shirts available. Over 100 styles www.gearink.com WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM is in your extended "it's an abomination that we are in an network. obama nation ... ron view more paul 2012 ... balance the budget and bring back tube WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM's Latest Blog Entry [ Subscribe to this Blog ] amps" [View All Blog Entries ] Male 43 years old PHILADELPHIA, Pennsylvania WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM's Blurbs United States About me: I have been an avid music collector since I was a kid. I ran a store for 20 years and now trade online. Last Login: 4/24/2009 I BUY PHONOGRAPH RECORDS ( 33 lp albums / 45 rpms / 78s ), COMPACT DISCS, DVD'S, CONCERT MEMORABILIA, VINTAGE POSTERS, BEATLES ITEMS, KISS ITEMS & More Mood: electric View My: Pics | Videos | Playlists Especially seeking Private Pressings / Psychedelic / Rockabilly / Be Bop & Avant Garde Jazz / Punk / Obscure '60s Funk & Soul Records / Original Contacting WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM concert posters 1950's & 1960's era / Original Beatles memorabilia I Offer A Professional Buying Service Of Music Items * LPs 45s 78s CDS DVDS Posters Beatles Etc.. Private Collections ** Industry Contacts ** Estates Large Collections / Warehouse finds ***** PAYMENT IN CASH ***** Over 20 Years experience buying collections MySpace URL: www.myspace.com/recordcastle I pay more for High Quality Collections In Excellent condition Let's Discuss What You May Have For Sale Call Or Email - 717 209 0797 Will Pick Up in Bucks County / Delaware County / Montgomery County / Philadelphia / South Jersey / Lancaster County / Berks County I travel the country for huge collections Print This Page - When You Are Ready To Sell Let Me Make An Offer ----------------------------------------------------------- Who I'd like to meet: WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM's Friend Space (Top 4) WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM has 57 friends. -

January 1988

VOLUME 12, NUMBER 1, ISSUE 99 Cover Photo by Lissa Wales Wales PHIL GOULD Lissa In addition to drumming with Level 42, Phil Gould also is a by songwriter and lyricist for the group, which helps him fit his drums into the total picture. Photo by Simon Goodwin 16 RICHIE MORALES After paying years of dues with such artists as Herbie Mann, Ray Barretto, Gato Barbieri, and the Brecker Bros., Richie Morales is getting wide exposure with Spyro Gyra. by Jeff Potter 22 CHICK WEBB Although he died at the age of 33, Chick Webb had a lasting impact on jazz drumming, and was idolized by such notables as Gene Krupa and Buddy Rich. by Burt Korall 26 PERSONAL RELATIONSHIPS The many demands of a music career can interfere with a marriage or relationship. We spoke to several couples, including Steve and Susan Smith, Rod and Michele Morgenstein, and Tris and Celia Imboden, to find out what makes their relationships work. by Robyn Flans 30 MD TRIVIA CONTEST Win a Yamaha drumkit. 36 EDUCATION DRIVER'S SEAT by Rick Mattingly, Bob Saydlowski, Jr., and Rick Van Horn IN THE STUDIO Matching Drum Sounds To Big Band 122 Studio-Ready Drums Figures by Ed Shaughnessy 100 ELECTRONIC REVIEW by Craig Krampf 38 Dynacord P-20 Digital MIDI Drumkit TRACKING ROCK CHARTS by Bob Saydlowski, Jr. 126 Beware Of The Simple Drum Chart Steve Smith: "Lovin", Touchin', by Hank Jaramillo 42 Squeezin' " NEW AND NOTABLE 132 JAZZ DRUMMERS' WORKSHOP by Michael Lawson 102 PROFILES Meeting A Piece Of Music For The TIMP TALK First Time Dialogue For Timpani And Drumset FROM THE PAST by Peter Erskine 60 by Vic Firth 104 England's Phil Seamen THE MACHINE SHOP by Simon Goodwin 44 The Funk Machine SOUTH OF THE BORDER by Clive Brooks 66 The Merengue PORTRAITS 108 ROCK 'N' JAZZ CLINIC by John Santos Portinho A Little Can Go Long Way CONCEPTS by Carl Stormer 68 by Rod Morgenstein 80 Confidence 116 NEWS by Roy Burns LISTENER'S GUIDE UPDATE 6 Buddy Rich CLUB SCENE INDUSTRY HAPPENINGS 128 by Mark Gauthier 82 Periodic Checkups 118 MASTER CLASS by Rick Van Horn REVIEWS Portraits In Rhythm: Etude #10 ON TAPE 62 by Anthony J. -

Wes Montgomery a Day in the Life Mp3, Flac, Wma

Wes Montgomery A Day In The Life mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: A Day In The Life Country: Japan Released: 1986 Style: Smooth Jazz MP3 version RAR size: 1310 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1301 mb WMA version RAR size: 1153 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 529 Other Formats: WAV RA TTA MP4 AIFF MP2 MPC Tracklist Hide Credits A Day In The Life A1 5:30 Written-By – Lennon-McCartney Watch What Happens A2 2:37 Written-By – M. Legrand*, N. Gimbel* When A Man Loves A Woman A3 2:48 Written-By – Wright*, Lewis* California Nights A4 2:35 Written-By – Liebling*, Hamlisch* Angel A5 2:46 Written-By – Wes Montgomery Eleanor Rigby B1 3:00 Written-By – Lennon-McCartney Willow Weep For Me B2 4:35 Written-By – Ann Ronnell* Windy B3 2:20 Written-By – Ruthann Friedman Trust In Me B4 4:23 Written-By – Schwartz*, Ager*, Wever* The Joker B5 3:00 Written-By – Newley*, Bricusse* Companies, etc. Recorded At – Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey Pressed By – Monarch Record Mfg. Co. Credits Arranged By, Conductor – Don Sebesky Bass – Ron Carter Cello – Alan Shulman, Charles McCracken Conductor – Don Sebesky Design [Album] – Sam Antupit Drums – Grady Tate Engineer – Rudy Van Gelder Flute [Bass] – George Marge, Joe Soldo, Romeo Penque, Stan Webb French Horn – Ray Alonge Harp – Margaret Ross Percussion – Jack Jennings, Joe Wohletz, Ray Barretto Photography By – Pete Turner Piano – Herbie Hancock Producer – Creed Taylor Viola – Emanuel Vardi, Harold Coletta Violin – Gene Orloff, Harry Glickman, Harry Katzman, Harry Urbont, Jack Zayde, Julius -

Eddie Who? - Eddie Harris Amerikansk Tenorsaxofonist, Født 20.10.1934 I Chicago, IL, D

Eddie Who? - Eddie Harris Amerikansk tenorsaxofonist, født 20.10.1934 i Chicago, IL, d. 5.11.1996 Sanger og pianist som barn i baptistkirker og spillede senere vibrafon og tenorsax. Debuterede som pianist med Gene Ammons før universitetsstudier i musik. Spillede med bl.a. Cedar Walton i 7. Army Symphony Orchestra. Fik i 1961 et stort hit og jazzens første guldplade med filmmelodien "Exodus", hvad der i de følgende år gav ham visse problemer med accept i jazzmiljøet. Udsendte 1965 The in Sound med bl.a. hans egen komposition Freedom Jazz Dance, som siden er indgået i jazzens standardrepertoire. Spillede fra 1966 elektrificeret saxofon og hybrider af sax og basun. Flirtede med rock på Eddie Harris In the UK (Atlantic 1969). Spillede 1969 på Montreux festivalen med Les McCann (Swiss Movement, Atlantic) og skrev 1969-71 musik til Bill Cosbys tv-shows. Spillede i 80'erne med bl.a. Tete Montoliu og Bo Stief (Steps Up, SteepleChase, 1981) og igen med Les McCann. Som sideman med bl.a. Jimmy Smith, Horace Silver, Horace Parlan og John Scofield (Hand Jive, Blue Note, 1993). Optrådte trods sygdom, så sent som maj 1996. Indspillede et stort antal plader for mange selskaber, fra 80'erne mest europæiske. Med udgangspunkt i bopmusikken udviklede Harris sine eksperimenter til en meget personlig stil med umiddelbart genkendelig, egenartet vokaliserende tone, fra 70'erne krydret med (ofte lange), humoristisk filosofisk/satiriske enetaler. Følte sig ofte underkendt som musiker og satiriserede over det i sin "Eddie Who". Kilde: Politikens Jazz Leksikon, 2003, red. Peter H. Larsen og Thorbjørn Sjøgren There's a guys (Chorus) You ought to know Eddie Harris .. -

Midnight Blue File:///C:/Sonotheque/1 JAZZ/Kenny Burrell/Midnight Blue/Catalogue

Midnight Blue file:///C:/Sonotheque/1_JAZZ/Kenny Burrell/Midnight Blue/catalogue... Sonotheque/Jazz/Kenny Burrell/Midnight Blue 01 Chitlins Con Carne 04 Midnight Blue 06 Gee Baby, Ain't I Good To You 08 Kenny's Sound (Take 10) 02 Mule 05 Wavy Gravy 07 Saturday Night Blues 09 K Twist (Take 35) 03 Soul Lament Except where otherwise noted, all songs composed by Kenny Burrell. "Chitlins con Carne" – 5:30 "Mule" (Burrell, Major Holley, Jr.) – 6:56 "Soul Lament" – 2:43 "Midnight Blue" – 4:02 "Wavy Gravy" – 5:47 "Gee Baby, Ain't I Good to You" (Andy Razaf, Don Redman) – 4:25 "Saturday Night Blues" – 6:16 "Kenny's Sound" (reissue bonus track) – 4:43 "K Twist" (reissue bonus track)– 3:36 Performance Kenny Burrell – guitar Stanley Turrentine – tenor saxophone Major Holley – bass Billy Gene English – drums Ray Barretto – conga Rudy Van Gelder – engineer, remastering Released 1963 Recorded January 8, 1963 Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs Genre Jazz, Jazz blues, Hardbop Length 35:39 original LP 45:18 CD reissue Label Blue Note BST 84123 Producer Michael Cuscuna, Alfred Lion, Tom Vasatka "The blues," Duke Ellington wrote, "the blues ain't nothin' but a cold grey day, and all night long it stays that way . the blues is a one-way ticket from your love to nowhere; the blues ain't nothin' but a black crepe veil ready to wear." That's the way Kenny Burrell felt when he talked with Alfred Lion about the idea for the album. "I have always had a love for the blues," he said. -

Milton Cardona

Milton Cardona Milton Cardona, a Puerto Rican percussionist who was a mainstay of New York salsa, a studio musician on hundreds of albums and a Santeria priest who introduced sacred traditional rhythms to secular audiences, died on Sept. 19 in the Bronx. He was 69. The cause was heart failure, said his wife, Bruni. In Latin bands and at recording sessions led by David Byrne, Paul Simon, Herbie Hancock and many others, Mr. Cardona primarily played conga drums — generally not as a flashy soloist but as the kinetic foundation and spark of a percussion section. He was an authoritative advocate for some of Latin music’s deepest traditions; he was also a vital, innovative participant in many ambitious fusions. Mr. Cardona worked with the trombonist and bandleader Willie Colón on and off through four decades and was a member of the singer Hector Lavoe’s band from 1974 to 1987. He also recorded two albums as a leader and led the Santeria group Eya Aranla. Mr. Cardona was a santero, a priest of Santeria, the Afro- Caribbean religion rooted in the Yoruba culture of West Africa. Santeria invokes a pantheon of African deities with rhythms and songs that have filtered into the popular music of Latin America and the world. Mr. Cardona studied the Yoruba language to understand the traditional prayers he was singing. “I always said, ‘Why should I learn the prayer if I don’t know what it means?’ ” he explained in an interview with Drum magazine. The rhythms of Santeria are traditionally played on batá drums, a family of three hand drums. -

The 2017 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2017 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

4-3 NEA JAZZ.qxp_WPAS 3/24/17 8:41 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN, Chairman DEBoRAh F. RUTTER, President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 3, 2017 at 7:30 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2017 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2017 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters DEE DEE BRIDGEWATER IRA GITLER DAVE HOLLAND DICK HYMAN DR. LONNIE SMITH Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz. This performance will be livestreamed online, and will be broadcast on Sirius XM Satellite Radio. WPFW 89.3 FM is a media partner of Kennedy Center Jazz. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 4-3 NEA JAZZ.qxp_WPAS 3/24/17 8:41 AM Page 2 THE 2017 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, Chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts DEBORAH F. RUTTER, President of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts KENNY BARRON, NEA Jazz Master DAN MORGENSTERN, NEA Jazz Master GARY GIDDINS, jazz and film critic JESSYE NORMAN, Kennedy Center Honoree and recipient, National Medal of Arts The 2017 NEA JAzz MASTERS Performances by PAQUITO D’RIVERA, saxophone LEE KONITz, alto saxophone Special Guests Bill Charlap, piano Sherrie Maricle and the Theo Croker, trumpet DIVA Jazz Orchestra Aaron Diehl, piano Sherrie Maricle, leader and drummer Robin Eubanks, trombone Tomoko Ohno, piano James Genus, bass Noriko Ueda, bass Donald Harrison, saxophone Jennifer Krupa , lead trombonist Booker T. -

Prestige Label Discography

Discography of the Prestige Labels Robert S. Weinstock started the New Jazz label in 1949 in New York City. The Prestige label was started shortly afterwards. Originaly the labels were located at 446 West 50th Street, in 1950 the company was moved to 782 Eighth Avenue. Prestige made a couple more moves in New York City but by 1958 it was located at its more familiar address of 203 South Washington Avenue in Bergenfield, New Jersey. Prestige recorded jazz, folk and rhythm and blues. The New Jazz label issued jazz and was used for a few 10 inch album releases in 1954 and then again for as series of 12 inch albums starting in 1958 and continuing until 1964. The artists on New Jazz were interchangeable with those on the Prestige label and after 1964 the New Jazz label name was dropped. Early on, Weinstock used various New York City recording studios including Nola and Beltone, but he soon started using the Rudy van Gelder studio in Hackensack New Jersey almost exclusively. Rudy van Gelder moved his studio to Englewood Cliffs New Jersey in 1959, which was close to the Prestige office in Bergenfield. Producers for the label, in addition to Weinstock, were Chris Albertson, Ozzie Cadena, Esmond Edwards, Ira Gitler, Cal Lampley Bob Porter and Don Schlitten. Rudy van Gelder engineered most of the Prestige recordings of the 1950’s and 60’s. The line-up of jazz artists on Prestige was impressive, including Gene Ammons, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Eric Dolphy, Booker Ervin, Art Farmer, Red Garland, Wardell Gray, Richard “Groove” Holmes, Milt Jackson and the Modern Jazz Quartet, “Brother” Jack McDuff, Jackie McLean, Thelonious Monk, Don Patterson, Sonny Rollins, Shirley Scott, Sonny Stitt and Mal Waldron.