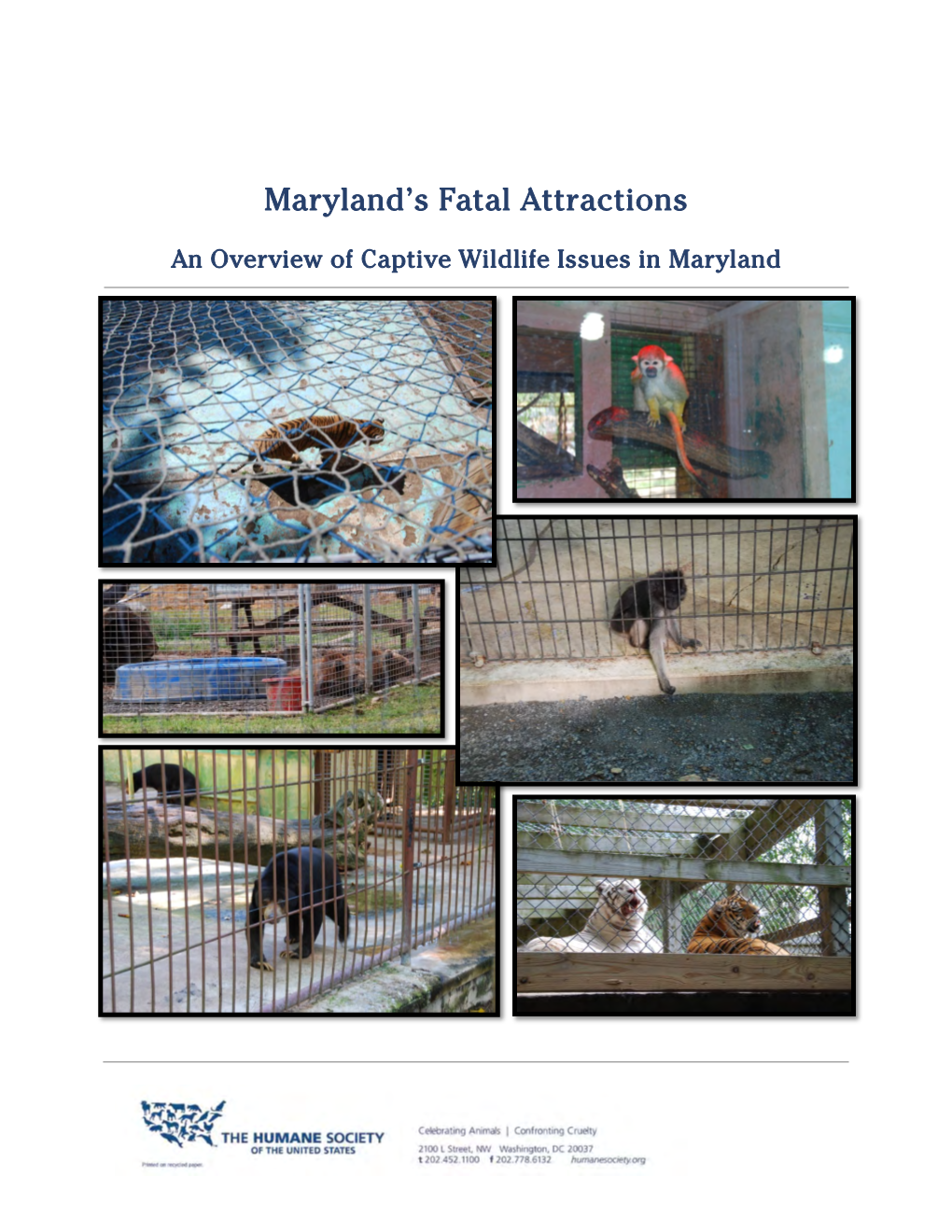

Maryland's Fatal Attractions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Increase Tourism's Economic Impact to Oakland Through Destination

Visitoakland.com #Oakland Love it Love #Oakland Visitoakland.com VISION: To tell the world that MISSION: Increase Tourism’s Economic Impact to Oakland Oakland is a world class destination through destination development and brand management 2016 - 2017 BOARD OF DIRECTORS a new portable visitor center will EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2016 / 17 be on the road to bring a bit of Michael LeBlanc, Chair, Pican the Oakland experience to many Sima Patel, Vice Chair, Ridgemont Hospitality different West Coast locations. Mark Hochstatter, Past Chair, Executive Inn & Suites Oakland has cause to celebrate in 2016-17, not only The Jack London Square Visitor and Best Western Plus Bayside Hotel for hosting another NBA parade, but for its continued Center has been renovated and Sam Nassif, Secretary, Z Hotel strong hotel performance in the Bay Area and its is ready to assist visitors with V. Toni Adams, Treasurer, recognition on a state-wide and national level. Visitors questions and suggestions. Alameda County Office of Education to Oakland set new records in visitation and visitor Lisa Kershner, At Large, Oakland Marriott City Center spending. Oakland’s performance in terms of year Visit Oakland hired an outside PR agency to assist in garnering more BOARD OF DIRECTORS over year growth of hotel occupancy and revenue out John Albrecht, Port of Oakland performed San Francisco and the Bay Area. This can be domestic press and also attended Carl Chan, Oakland Chinatown Chamber Foundation attributed to the foresight of Oakland hoteliers. Several sales and media missions in the UK, Canada and Mexico. Layered Leonard Czarnecki, Claremont Club and Spa - Oakland hotels entered the year fully renovated with a Fairmont Hotel on top of the public relations new products and services. -

Petition to List Mountain Lion As Threatened Or Endangered Species

BEFORE THE CALIFORNIA FISH AND GAME COMMISSION A Petition to List the Southern California/Central Coast Evolutionarily Significant Unit (ESU) of Mountain Lions as Threatened under the California Endangered Species Act (CESA) A Mountain Lion in the Verdugo Mountains with Glendale and Los Angeles in the background. Photo: NPS Center for Biological Diversity and the Mountain Lion Foundation June 25, 2019 Notice of Petition For action pursuant to Section 670.1, Title 14, California Code of Regulations (CCR) and Division 3, Chapter 1.5, Article 2 of the California Fish and Game Code (Sections 2070 et seq.) relating to listing and delisting endangered and threatened species of plants and animals. I. SPECIES BEING PETITIONED: Species Name: Mountain Lion (Puma concolor). Southern California/Central Coast Evolutionarily Significant Unit (ESU) II. RECOMMENDED ACTION: Listing as Threatened or Endangered The Center for Biological Diversity and the Mountain Lion Foundation submit this petition to list mountain lions (Puma concolor) in Southern and Central California as Threatened or Endangered pursuant to the California Endangered Species Act (California Fish and Game Code §§ 2050 et seq., “CESA”). This petition demonstrates that Southern and Central California mountain lions are eligible for and warrant listing under CESA based on the factors specified in the statute and implementing regulations. Specifically, petitioners request listing as Threatened an Evolutionarily Significant Unit (ESU) comprised of the following recognized mountain lion subpopulations: -

Meerkats (Suricata Suricatta), a New Definitive Host of the Canid Nematode Angiostrongylus Vasorum

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2017 Meerkats ( Suricata suricatta ), a new definitive host of the canid nematode Angiostrongylus vasorum Gillis-Germitsch, Nina ; Manser, Marta B ; Hilbe, Monika ; Schnyder, Manuela DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijppaw.2017.10.002 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-141634 Journal Article Published Version The following work is licensed under a Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License. Originally published at: Gillis-Germitsch, Nina; Manser, Marta B; Hilbe, Monika; Schnyder, Manuela (2017). Meerkats ( Suricata suricatta ), a new definitive host of the canid nematode Angiostrongylus vasorum. International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife, 6(3):349-353. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijppaw.2017.10.002 IJP: Parasites and Wildlife 6 (2017) 349–353 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect IJP: Parasites and Wildlife journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijppaw Meerkats (Suricata suricatta), a new definitive host of the canid nematode MARK Angiostrongylus vasorum ∗ Nina Gillis-Germitscha, Marta B. Manserb, Monika Hilbec, Manuela Schnydera, a Institute of Parasitology, Vetsuisse-Faculty, University of Zurich, Winterthurerstrasse 266a, 8057 Zurich, Switzerland b Department of Evolutionary Biology and Environmental Studies, University of Zurich, Winterthurerstrasse 190, 8057 Zurich, Switzerland c Institute of Veterinary Pathology, Vetsuisse-Faculty, University of Zurich, Winterthurerstrasse 268, 8057 Zurich, Switzerland ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Angiostronglyus vasorum is a cardiopulmonary nematode infecting mainly canids such as dogs (Canis familiaris) Angiostrongylus vasorum and foxes (Vulpes vulpes). -

Zoo Liability Supplemental Application (Complete in Addition to General Application and General Liability Renewal Application)

*Please visit www.allrisks.com/submit-a-risk or contact your current All Risks, Ltd. producer to submit applications. Zoo Liability Supplemental Application (Complete in addition to General Application and General Liability Renewal Application) Applicant’s Name: PROPOSED EFFECTIVE DATE: From To 12:01 A.M., Standard Time at the address of the Applicant PLEASE ANSWER ALL QUESTIONS—IF THEY DO NOT APPLY, INDICATE “NOT APPLICABLE” APPLICANT PREMISES OPERATIONS INFORMATION 1. Named Insured as it is to appear on policy: 2. Doing Business As: 3. Mailing Address: 4. Location of business (if different): City: State: Zip Code: Phone Number: 5. Contact person: Title: Daytime phone: Nighttime phone: Fax No.: 6. Website Address: 7. Type of Institution: Aquarium Petting Zoo Wildlife Park Zoological Park For Profit Non Profit Other—Describe: 8. Average Daily Attendance: Maximum Daily Attendance: Total Annual Attendance: 9. Hours of Operations: In Season: to Off Season: to Describe off-season activities or promotions: 10. Total Acres: 11. Revenues: Admission Charge $ Membership/Contributions/etc. $ Alcoholic Beverages $ Souvenier/Gift Shop Receipts $ Food/Beverage $ Stroller Rentals $ Horse Drawn or Motorized Rides $ Trail Rides $ Pumpkin Patch, Corn Maze $ Wheelchair Rentals $ Ponies, Elephants, Camels or $ Other—Explain: $ Other Zoo Animals Rides Total Annual Revenue from all Sources $ 12. Is the institution accredited by the AZA (Association of Zoos and Aquariums)? ........................................................ Yes No 13. Who staffs the applicant’s first aid station? Doctor Nurse Other—explain: 14. Number of employees: Full-time: Part-time: Volunteers: Explain volunteers’ responsibilities: Zoo Liability Supplemental Application – 02.17 Page 1 of 4 Do volunteers sign waivers of liability? ........................................................................................................................ -

The Disastrous Impacts of Trump's Border Wall on Wildlife

a Wall in the Wild The Disastrous Impacts of Trump’s Border Wall on Wildlife Noah Greenwald, Brian Segee, Tierra Curry and Curt Bradley Center for Biological Diversity, May 2017 Saving Life on Earth Executive Summary rump’s border wall will be a deathblow to already endangered animals on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border. This report examines the impacts of construction of that wall on threatened and endangered species along the entirety of the nearly 2,000 miles of the border between the United States and Mexico. TThe wall and concurrent border-enforcement activities are a serious human-rights disaster, but the wall will also have severe impacts on wildlife and the environment, leading to direct and indirect habitat destruction. A wall will block movement of many wildlife species, precluding genetic exchange, population rescue and movement of species in response to climate change. This may very well lead to the extinction of the jaguar, ocelot, cactus ferruginous pygmy owl and other species in the United States. To assess the impacts of the wall on imperiled species, we identified all species protected as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act, or under consideration for such protection by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (“candidates”), that have ranges near or crossing the border. We also determined whether any of these species have designated “critical habitat” on the border in the United States. Finally, we reviewed available literature on the impacts of the existing border wall. We found that the border wall will have disastrous impacts on our most vulnerable wildlife, including: 93 threatened, endangered and candidate species would potentially be affected by construction of a wall and related infrastructure spanning the entirety of the border, including jaguars, Mexican gray wolves and Quino checkerspot butterflies. -

Helogale Parvula)

Vocal Recruitment in Dwarf Mongooses (Helogale parvula) Janneke Rubow Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the Faculty of Science at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof. Michael I. Cherry Co-supervisor: Dr. Lynda L. Sharpe March 2017 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Janneke Rubow, March 2017 Copyright © 2017 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract Vocal communication is important in social vertebrates, particularly those for whom dense vegetation obscures visual signals. Vocal signals often convey secondary information to facilitate rapid and appropriate responses. This function is vital in long-distance communication. The long-distance recruitment vocalisations of dwarf mongooses (Helogale parvula) provide an ideal opportunity to study informative cues in acoustic communication. This study examined the information conveyed by two recruitment calls given in snake encounter and isolation contexts, and whether dwarf mongooses are able to respond differently on the basis of these cues. Vocalisations were collected opportunistically from four wild groups of dwarf mongooses. The acoustic parameters of recruitment calls were then analysed for distinction between contexts within recruitment calls in general, distinction within isolation calls between groups, sexes and individuals, and the individuality of recruitment calls in comparison to dwarf mongoose contact calls. -

Vancouver, British Columbia Destination Guide

Vancouver, British Columbia Destination Guide Overview of Vancouver Vancouver is bustling, vibrant and diverse. This gem on Canada's west coast boasts the perfect combination of wild natural beauty and modern conveniences. Its spectacular views and awesome cityscapes are a huge lure not only for visitors but also for big productions, and it's even been nicknamed Hollywood North for its ever-present film crews. Less than a century ago, Vancouver was barely more than a town. Today, it's Canada's third largest city and more than two million people call it home. The shiny futuristic towers of Yaletown and the downtown core contrast dramatically with the snow-capped mountain backdrop, making for postcard-pretty scenes. Approximately the same size as the downtown area, the city's green heart is Canada's largest city park, Stanley Park, covering hundreds of acres filled with lush forest and crystal clear lakes. Visitors can wander the sea wall along its exterior, catch a free trolley bus tour, enjoy a horse-drawn carriage ride or visit the Vancouver Aquarium housed within the park. The city's past is preserved in historic Gastown with its cobblestone streets, famous steam-powered clock and quaint atmosphere. Neighbouring Chinatown, with its weekly market, Dr Sun Yat-Sen classical Chinese gardens and intriguing restaurants add an exotic flair. For some retail therapy or celebrity spotting, there is always the trendy Robson Street. During the winter months, snow sports are the order of the day on nearby Grouse Mountain. It's perfect for skiing and snowboarding, although the city itself gets more rain than snow. -

A Toolkit to Engage in Field Conservation

A Toolkit to Engage in Field Conservation created by the AZA Field Conservation Committee 3rd Edition, December 2018 Dear colleagues, As an accredited or certified related facility of the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, the mission of your organization is rooted in conservation. This means that regardless of your role at the organization, your job includes helping to save wildlife and wild places. You also likely know what is happening to animals and plants in the wild and that many scientists believe we are experiencing Earth’s sixth mass extinction. This means we all need to do our job of saving wildlife and wild places better, and this toolkit can help us meet the challenge. The content included in this toolkit focuses on overcoming the obstacles that stop us from helping animals and plants in the wild - like a limited budget, or a governing body resistant to spending funds on efforts outside the facility. This toolkit is neither a primer on the threats facing wildlife nor does it explore methodologies to implement conservation in the field, develop conservation education programs that lead to changed behaviors, reduce the use of natural resources in business operations or conduct scientific research that may ultimately inform conservation, as resources for those important issues are available elsewhere. As an AZA member, you know the power of collaboration. What we can do together can have a profound impact in our communities and around the world. Already, the AZA community spends more than $200 million each year on field conservation with a direct impact on animals and habitats in the wild. -

First Record of Hose's Civet Diplogale Hosei from Indonesia

First record of Hose’s Civet Diplogale hosei from Indonesia, and records of other carnivores in the Schwaner Mountains, Central Kalimantan, Indonesia Hiromitsu SAMEJIMA1 and Gono SEMIADI2 Abstract One of the least-recorded carnivores in Borneo, Hose’s Civet Diplogale hosei , was filmed twice in a logging concession, the Katingan–Seruyan Block of Sari Bumi Kusuma Corporation, in the Schwaner Mountains, upper Seruyan River catchment, Central Kalimantan. This, the first record of this species in Indonesia, is about 500 km southwest of its previously known distribution (northern Borneo: Sarawak, Sabah and Brunei). Filmed at 325The m a.s.l., IUCN these Red List records of Threatened are below Species the previously known altitudinal range (450–1,800Prionailurus m). This preliminary planiceps survey forPardofelis medium badia and large and Otter mammals, Civet Cynogalerunning 100bennettii camera-traps in 10 plots for one (Bandedyear, identified Civet Hemigalus in this concession derbyanus 17 carnivores, Arctictis including, binturong on Neofelis diardi, three Endangered Pardofe species- lis(Flat-headed marmorata Cat and Sun Bear Helarctos malayanus, Bay Cat . ) and six Vulnerable species , Binturong , Sunda Clouded Leopard , Marbled Cat Keywords Cynogale bennettii, as well, Pardofelis as Hose’s badia Civet), Prionailurus planiceps Catatan: PertamaBorneo, camera-trapping, mengenai Musang Gunung Diplogale hosei di Indonesia, serta, sustainable karnivora forest management lainnya di daerah Pegunungan Schwaner, Kalimantan Tengah Abstrak Diplogale hosei Salah satu jenis karnivora yang jarang dijumpai di Borneo, Musang Gunung, , telah terekam dua kali di daerah- konsesi hutan Blok Katingan–Seruyan- PT. Sari Bumi Kusuma, Pegunungan Schwaner, di sekitar hulu Sungai Seruya, Kalimantan Tengah. Ini merupakan catatan pertama spesies tersebut terdapat di Indonesia, sekitar 500 km dari batas sebaran yang diketa hui saat ini (Sarawak, Sabah, Brunei). -

Photographic Evidence of a Jaguar (Panthera Onca) Killing an Ocelot (Leopardus Pardalis)

Received: 12 May 2020 | Revised: 14 October 2020 | Accepted: 15 November 2020 DOI: 10.1111/btp.12916 NATURAL HISTORY FIELD NOTES When waterholes get busy, rare interactions thrive: Photographic evidence of a jaguar (Panthera onca) killing an ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) Lucy Perera-Romero1 | Rony Garcia-Anleu2 | Roan Balas McNab2 | Daniel H. Thornton1 1School of the Environment, Washington State University, Pullman, WA, USA Abstract 2Wildlife Conservation Society – During a camera trap survey conducted in Guatemala in the 2019 dry season, we doc- Guatemala Program, Petén, Guatemala umented a jaguar killing an ocelot at a waterhole with high mammal activity. During Correspondence severe droughts, the probability of aggressive interactions between carnivores might Lucy Perera-Romero, School of the Environment, Washington State increase when fixed, valuable resources such as water cannot be easily partitioned. University, Pullman, WA, 99163, USA. Email: [email protected] KEYWORDS activity overlap, activity patterns, carnivores, interspecific killing, drought, climate change, Funding information Maya forest, Guatemala Coypu Foundation; Rufford Foundation Associate Editor: Eleanor Slade Handling Editor: Kim McConkey 1 | INTRODUCTION and Johnson 2009). Interspecific killing has been documented in many different pairs of carnivores and is more likely when the larger Interference competition is an important process working to shape species is 2–5.4 times the mass of the victim species, or when the mammalian carnivore communities (Palomares and Caro 1999; larger species is a hypercarnivore (Donadio and Buskirk 2006; de Donadio and Buskirk 2006). Dominance in these interactions is Oliveria and Pereira 2014). Carnivores may reduce the likelihood often asymmetric based on body size (Palomares and Caro 1999; de of these types of encounters through the partitioning of habitat or Oliviera and Pereira 2014), and the threat of intraguild strife from temporal activity. -

2016 Report to the Governor and the Minnesota State Legislature On

2016 Report to the Governor and the Minnesota State Legislature on Funding for Minnesota Zoo Programs supported by the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund Introduction The Minnesota Zoo was established by the State Legislature to foster a partnership between the private sector and the state for the purpose of operating a zoological garden. The “New Zoo” opened to the public in 1978 and has grown into a world-leading zoo and recognized leader in family recreation, environmental education, and conservation. The mission of the Minnesota Zoo is to connect people, animals and the natural world to save wildlife. Today, more than 4,700 animals representing 400+ species (many of which are endangered or threatened) reside at the Zoo. Funding from the Clean Water, Land and Legacy Amendment has propelled the expansion of the Zoo’s conservation, conservation education, Minnesota farm heritage, Minnesota natural heritage, and Zoo site habitat and landscape programs for the benefit of the citizens of our state. A Statewide Resource The Minnesota Zoo is of one of two state-run zoos in the country and provides programs and services that reach every corner of the state. Legacy appropriations have provided critical funds that have been used toward programs that expand and enhance this service and bring our conservation efforts into Greater Minnesota. In FY15, the Zoo’s service to the state included: 1.2 million guests, including 41,100 member households from 83 Minnesota counties Minnesota’s #1 environmental education center, serving 500,000+ participants each year 120,000 free admission passes distributed through 87 county agencies and dozens Field conservation activities in Northwestern, Northeastern and Southwestern Minnesota Appropriation Summary This report highlights projects paid for with Legacy appropriations in FY16 and provides updates on projects funded in FY15, for which funds are available through June 30, 2016. -

Moose Are One of Minnesota's Most Prized Wildlife Species. in Less Than

2010 Project Abstract For the Period Ending June 30, 2012 PROJECT TITLE: Identifying Critical Habitats for Moose in Northeastern Minnesota PROJECT MANAGER: Ronald A. Moen AFFILIATION: Natural Resources Research Institute, University of Minnesota Duluth MAILING ADDRESS: 5013 Miller Trunk Highway CITY/STATE/ZIP: Duluth, MN 55811-1442 PHONE: (218) 720-7372 E-MAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: http://www.nrri.umn.edu/moose FUNDING SOURCE: Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund LEGAL CITATION: ML 2010, Chap. 362, Sec. 2, Subd. 3(k) APPROPRIATION AMOUNT: $507,000 Overall Project Outcome and Results Moose are one of Minnesota’s most prized wildlife species. In less than 20 years moose in northwestern Minnesota declined from over 4,000 to fewer than 100. The northeastern Minnesota moose population, which had over 7,000 moose until 2009, is in the middle of what appears to be a similar decline. Higher mortality in radiocollared moose is correlated with warmer temperatures. We used satellite collars to track moose in northeastern Minnesota and collected GPS locations day and night 365 days a year. Over 2 million moose locations and activity data were obtained. Specific habitats needed by moose were identified using the satellite collars. Spatial distribution and availability of habitat types has guided identification of specific sites for enhancement, protection, or acquisition. Habitat guidelines and recommendations help private and public land managers provide the best possible habitat for moose. The project was part of a coordinated effort involving many resource management agencies to determine if it is possible to slow or prevent a decline in the northeastern MN moose population.