Managing Agencies and the Dalmia Jain Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

~D/Jfw Incorporating the 'Free E~Nomlc Rel'iew'

1/ Xr:, :;. ) lJ :;· Vol. :VI No. 3 April 15, 1958 ~d/Jfw Incorporating the 'Free E~nomlc ReL'iew' INDEPE.'WE!'.'T JoURNAL OF Eco:so~nc AND Puuuc AFFAIRS ~n · WE STAND FOR FREE ECONOMY IN THIS ISSUE Letters to the Editor 2 EDITORIAL 3 India and Islam by 111. A. Venkata Rao 5 Untimely Cloud Over India .....• 7 Khrushchev Reaches the Pinnacle by T. L. Kantam 9 India and the Middle-East by Sumant Bankeshwar 11 Abolish Caste By Legislation by S. Ramanathan 13 What Is Libertarianism? 17 "The Personality Cult In India by Lal 18 Nehru Is Crying For The Moon by Kis1wre Valicha 20 Where Does Mri~ulla Get Money for Anti-Indian Propaganda? 21 On the News Front •11 22 Book Reviews 25 • ltlake English the Official Language ·of India Unleso specified publication or matter does .. not neoessarllJ mean editorial endorsement Priee 25 Naye Paise • by twenty years involved ·the fre ezing of two hundred sixty billion Letters r roubles loaned to the State by the To. public. This is one of the exam The Indian Libertarian The Editor ples of communist disregard for the right of the people who, in good Indt,..ndm ]oumDI of Economic faith, subscribed to the state loans. tmd Public Alfairs WHY THIS IN.-U::TION ON THE Bombay Sumant S. Bankeshwar PART OF NEW DELHI? Ecllted by Dear 1\ladam: Speaking at New STOOPING TO CONQUER THE MISS Kusmr LonvALA Delhi Bakshi Ghulam Mahomed SHEIKH Pnhli<hed on the 1st ond 15th of asse~ that the Jammu and Kash Eoch \llonth mir Government .,..,ould not hesitate Dear Madam: It is surprising ' in takin~ strong action a~ainst that the present Chief Minister of Sheikh Abdullah: But the trouble Jammu and Kashmir State should SiDrle Copy 25 Naye Paise was that New Delhi was the centre have offered, on a silver platter so from which subversive activities to say, the premiership of the State Subscription Rat~.r: were directed in the State. -

Major Scams in India Since 1947: a Brief Sketch

© 2015 JETIR July 2015, Volume 2, Issue 7 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Major Scams in India since 1947: A Brief Sketch Naveen Kumar Research Scholar Deptt. of History B.R.A.B.U. Muzaffarpur "I would go to the length of giving the whole congress a decent burial, rather than put up with the corruption that is rampant." - Mahatma Gandhi. This was the outburst of Mahatma Gandhi against rampant corruption in Congress ministries formed under 1935 Act in six states in the year 1937.1 The disciples of Gandhi however, ignored his concern over corruption in post-Independence India, when they came to power. Over fifty years of democratic rule has made the people so immune to corruption that they have learnt how to live with the system even though the cancerous growth of this malady may finally kill it. Politicians are fully aware of the corruption and nepotism as the main reasons behind the fall of Roman empire,2 the French Revolution,3 October Revolution in Russia,"4 fall of Chiang Kai-Sheik Government on the mainland of China5 and even the defeat of the mighty Congress party in India.6 But they are not ready to take any lesson from the pages of history. JEEP PURCHASE (1948) The history of corruption in post-Independence India starts with the Jeep scandal in 1948, when a transaction concerning purchase of jeeps for the army needed for Kashmir operation was entered into by V.K.Krishna Menon, the then High Commissioner for India in London with a foreign firm without observing normal procedure.7 Contrary to the demand of the opposition for judicial inquiry as suggested by the Inquiry Committee led by Ananthsayanam Ayyangar, the then Government announced on September 30, 1955 that the Jeep scandal case was closed. -

![3941 Life Insurance [ 11 SEP. 1959 ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9992/3941-life-insurance-11-sep-1959-2239992.webp)

3941 Life Insurance [ 11 SEP. 1959 ]

3941 Life Insurance [ 11 SEP. 1959 ] Corporation Inquiry 3942 DISCUSSION ON THE GOVERN- independence of their judgment, for the MENT RESOLUTION ON THE LIFE admirably clear analysis of the various issues INSURANCE CORPORATION that were involved and for the fairness with INQUIRY which the Commission dealt with every issue. Sir, my regret is great that the Government, in MR. CHAIRMAN: Half an hour is the its final Resolution, did not see its way to the maximum for you. acceptance, to the unreserved acceptance, of the conclusions of the Commission. I am not SHRI B. SHIVA RAO (Mysore): Mr. interested in Mr. Patel as an individual. But I Chairman, Sir, I move: am interested, and I hope the House is interested vitally, in the treatment that is meted out to a civil servant who has put in 35 "That the decisions of the Government of years of distinguished service in many fields, India on the findings of the recent inquiry a man of unusual ability, great drive and into certain affairs of the Life Insurance resourcefulness and integrity. It is not good Corporation as embodied in Government enough to be told at the end of that long Resolution No. F. 15|58-HS, dated the 27 period of service: "You may go because th May, 1959, be taken into consideration." although six Members of the Commission have completely exonerated you, one Member Sir, my main purpose in giving notice of of the Commission has said without this motion is to invite the attention of the supporting his conclusions, that you have House and also of the Government to some been reckless and defiant." general issues of far-reaching importance which seem to me to arise out of this unhappy Sir, in the past, the Government had been episode. -

Promoting Transparency Understanding Corruption in India 2 of 2

Understanding Corruption in India: Promoting Transparency Understanding Corruption in India 2 of 2 Table of Contents Topic Page No. Overview of Current Scenario ---------------------------- 3 Brief History of Corruption -------------------------------- 4 What is Corruption? ---------------------------------------- 5 Financial Scams in India ----------------------------------- 7 15 High Profile Scandals ------------------------------------ 8 Nature of Corruption in India---------------------------- 12 Legislative Corruption --------------------------------------13 Corruption in the executive---------------------------------13 Corruption in the Judiciary----------------------------------14 Political corruption ------------------------------------------15 Vulnerable Sectors and Institutions -------------------- 15 Public Procurement------------------------------------------15 Tax and Customs--------------------------------------------16 The Police Force ---------------------------------------------16 Regional Patterns -------------------------------------------16 Corruption and Money Laundering ---------------------- 17 Anti-Corruption Framework in India-------------------- 18 The Legal framework----------------------------------------18 No Protection to Whistleblowers----------------------------19 The Institutional Framework--------------------------------19 Pending Anti-Corruption Legislation------------------------21 Summary ----------------------------------------------------21 Lokpal Bill Vs Jan Lokpal Bill ---------------------------- -

Heritage, Culture & Identity Re-Negotiating Spaces of Memory

Seminar Brochure ICSSR Sponsored Two-Day Interdisciplinary International Seminar Organised by Sarat Centenary College in Collaboration with West Bengal Heritage Commission 20 & 21 January 2020 Heritage, Culture & Identity Re-Negotiating Spaces of Memory in a Time of Rapid Urbanisation ICSSR Sponsored Two-Day Interdisciplinary International Seminar Organised by Sarat Centenary College in Collaboration with West Bengal Heritage Commission on Heritage, Culture & Identity Re-Negotiating Spaces of Memory in a Time of Rapid Urbanisation 20 & 21 January 2020 Seminar Organising Core Committee Patron: Janab Md. Hanif, President, Governing Body, Sarat Centenary College Chairperson: Dr Sandip Kumar Basak, Principal, Sarat Centenary College [email protected] Convenor: Dr Ramanuj Konar, Assistant Professor, IQAC Coordinator, Sarat Centenary College; Editor, postScriptum <postscriptum.co.in> [email protected] Co-Convenor: Dr Basudeb Malik, Officer on Special Duty, West Bengal Heritage Commission, Govt. of WB [email protected] Treasurer: Prof. Basudev Halder, Assistant Professor, Bursar, Sarat Centenary College [email protected] Asstt. Treasurer: Shri Shyamal Bhattacharya, Accountant, Sarat Centenary College [email protected] This open access seminar brochure is published by The Principal <[email protected]>, Sarat Centenary College <sccollegednk.ac.in>, at Dhaniakhali on 20 January 2020 Concept & Design: Dr Ramanuj Konar Seminar Brochure 1 International Seminar Sarat Centenary College 20 & 21 January 2020 Concept Note of the Seminar Since the 1990s, after the effects of Globalisation started spreading all over, the process of urbanisation has entered rapid stage of acceleration. As per global data, 54% of total global population was living in urban areas in 2014 and it is projected that by the year 2050 the figure will reach 66%. -

Nr. 54 Mai 2009

LEADOFF In dieser Ausgabe Liebe Mitglieder, am 30. April hat Barack Obama 1 Mythos Rommel die 100 Tage-Marke seiner Amts- Maxim Worcester zeit als Präsident der U.S.A. pmg überschritten. Mit sportlichem pmg Tempo und voller Agenda hat er 2 Evaluating the sich auf den Weg gemacht. Das Obama admini- führt auch bei einem „Mythos“ wie ihm zu ganz unterschiedlichen stration's Reaktionen, wie Sie sich in den national security beiden Beiträgen zu seiner Amts- führung überzeugen können. budget and plan- Mit der „54“ erhalten Sie eine „mythische“ Ausgabe der ning process Denkwürdigkeiten – vom Mythos Gordon Adams „Rommel“ zum schon-Mythos „Obama“ zum demnächst-Mythos 3 Please Excuse me „Zuma“, abgerundet durch Korruption und Korruptionsbe- for Apologizing kämpfung in Indien und China. Laurent Murawiec Afrika und Asien stehen Europa und Amerika näher denn je. Räumlich und zeitlich stellen sie 5 South Africa's uns vor umfassende Heraus- next Big Man forderungen. Wer geschichtliche Maxim Worcester und kulturelle Zusammenhänge versteht, kann Zukunft nach- haltiger gestalten (yes we can). 6 India’s Tryst Eine Aufgabe nicht nur für Barack with Corruption Obama. Menace Ralph Thiele, Vorstandsvorsitzender Dr. Sheo Nandan Pandey THEMEN 10 Korruption und Mythos Rommel Militärgeschichte ist in Deutsch- Korruptions- land, im Unterschied zu den an- bekämpfung in gelsächsischen Ländern, eher ein Randgebiet. Dies hat natürlich mit der VR China Journal der der militärischen Katastrophe des Dr. Peter Roell Politisch- Zweiten Weltkriegs und der Ver- strickung der Wehrmacht in die Militärischen Verbrechen des national- sozialistischen Regimes zu tun. Gesellschaft Gerade deshalb ist die Aus- stellung über Rommel im Haus der Geschichte Baden- Württembergs in Stuttgart zu be- grüßen. -

The High Court at Calcutta 150 Years : an Overview

1 2 The High Court at Calcutta 150 Years : An Overview 3 Published by : The Indian Law Institute (West Bengal State Unit) iliwbsu.in Printed by : Ashutosh Lithographic Co. 13, Chidam Mudi Lane Kolkata 700 006 ebook published by : Indic House Pvt. Ltd. 1B, Raja Kalikrishna Lane Kolkata 700 005 www.indichouse.com Special Thanks are due to the Hon'ble Justice Indira Banerjee, Treasurer, Indian Law Institute (WBSU); Mr. Dipak Deb, Barrister-at-Law & Sr. Advocate, Director, ILI (WBSU); Capt. Pallav Banerjee, Advocate, Secretary, ILI (WBSU); and Mr. Pradip Kumar Ghosh, Advocate, without whose supportive and stimulating guidance the ebook would not have been possible. Indira Banerjee J. Dipak Deb Pallav Banerjee Pradip Kumar Ghosh 4 The High Court at Calcutta 150 Years: An Overview तदॆततत- क्षत्रस्थ क्षत्रैयद क्षत्र यद्धर्म: ।`& 1B: । 1Bद्धर्म:1Bत्पटैनास्ति।`抜֘टै`抜֘$100 नास्ति ।`抜֘$100000000स्ति`抜֘$1000000000000स्थक्षत्रैयदत । तस्थ क्षत्रै यदर्म:।`& 1Bण । ᄡC:\Users\सत धर्म:" ।`&ﲧ1Bशैसतेधर्मेण।h अय अभलीयान् भलीयौसमाशयनास्ति।`抜֘$100000000 भलीयान् भलीयौसमाशयसर्म: ।`& य राज्ञाज्ञा एवम एवर्म: ।`& 1B ।। Law is the King of Kings, far more powerful and rigid than they; nothing can be mightier than Law, by whose aid, as by that of the highest monarch, even the weak may prevail over the strong. Brihadaranyakopanishad 1-4.14 5 Copyright © 2012 All rights reserved by the individual authors of the works. All rights in the compilation with the Members of the Editorial Board. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the copyright holders. -

Managing Agencies and the Dalmia Jain Case

MPRA Munich Personal RePEc Archive Of Traders, Usurers and British Capital: Managing Agencies and the Dalmia Jain Case Nasir Tyabji 2009 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/79136/ MPRA Paper No. 79136, posted 15 May 2017 07:21 UTC 88 Of Traders, Usurers and British Capital Managing Agencies and the Dalmia Jain Case Nasir Tyabji The Problem Posed The years between 1947 and 1966, covering the period from Independence to the end of the Third Five Year Plan, provided the arena for the most acute debates over the content of industrial development. In essence, these controversies centred on the form of ownership and control of the industrial undertakings which were already in operation and those which were to be established. Primarily at issue, thus, were the roles of the public sector and of the private sector on the one hand, and of Indian and foreign capital within the private sector, on the other. Equally debated at the time was the form of industrial organisation that was appropriate for the private sector under a system of socially regulated industrialisation. In particular, the Managing Agency System, linking a closely held decision making organisation allied to joint stock companies came under extensive scrutiny. This system, originated as an organisational form during the East India Company’s retreat from monopoly in India’s external trade, and subsequently served as the vehicle for British and Indian enterprise in trade and industry.1 Though this system had supporters right upto the time it was abolished in 1969, the myriad methods available for financial manipulation it provided had made it the basis for criticism since at least the time from which Indian industry’s performance came under scrutiny with the establishment of the Indian Industrial Commission over 50 years earlier. -

Abhishek Sharma)

www.whiteblacklegal.co.in ISSN: 2581-8503 VOLUME 2 : ISSUE 1 || May 2020 || Email: [email protected] Website: www.whiteblacklegal.co.in 1 www.whiteblacklegal.co.in ISSN: 2581-8503 DISCLAIMER No part of this publication may be reproduced or copied in any form by any means without prior written permission of Editor-in-chief of White Black Legal – The Law Journal. The Editorial Team of White Black Legal holds the copyright to all articles contributed to this publication. The views expressed in this publication are purely personal opinions of the authors and do not reflect the views of the Editorial Team of White Black Legal. Though all efforts are made to ensure the accuracy and correctness of the information published, White Black Legal shall not be responsible for any errors caused due to oversight or otherwise. 2 www.whiteblacklegal.co.in ISSN: 2581-8503 EDITORIAL TEAM EDITOR IN CHIEF Name - Mr. Varun Agrawal Consultant || SUMEG FINANCIAL SERVICES PVT.LTD. Phone - +91-9990670288 Email - [email protected] EDITOR Name - Mr. Anand Agrawal Consultant|| SUMEG FINANCIAL SERVICES PVT.LTD. EDITOR (HONORARY) Name - Smt Surbhi Mittal Manager || PSU EDITOR(HONORARY) Name - Mr Praveen Mittal Consultant || United Health Group MNC EDITOR Name - Smt Sweety Jain Consultant||SUMEG FINANCIAL SERVICES PVT.LTD. EDITOR Name - Mr. Siddharth Dhawan Core Team Member || Legal Education Awareness Foundation 3 www.whiteblacklegal.co.in ISSN: 2581-8503 ABOUT US WHITE BLACK LEGAL is an open access, peer-reviewed and refereed journal provide dedicated to express views on topical legal issues, thereby generating a cross current of ideas on emerging matters. -

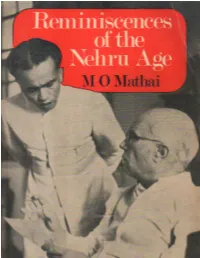

Reminiscences of the Nehru Age

REMINISCENCES OF THE NEHRU AGE M. O. Mathai Reproduced by Sani H. Panhwar (2021) To Priya, two, and Kavitha, five— two lively neighbourhood children who played with me, often dodging their parents, during the period of writing this book Contents Preface .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 1 1 Nehru and I .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 3 2 Attack on me by the Communists .. .. .. .. .. .. 15 3 Personal Embarrassment of a Rebel .. .. .. .. .. .. 18 4 Obscurantists to the Fore .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 20 5 Mahatma Gandhi .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 23 6 Lord Mountbatten and "Freedom at Midnight" .. .. .. .. .. 35 7 Earl Mountbatten of Burma .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 41 8 Churchill, Nehru and India .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 45 9 Nehru's Meeting with Bernard Shaw .. .. .. .. .. .. 51 10 C. Rajagopalachari .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 56 11 The Position of the President of India .. .. .. .. .. 58 12 Rajendra Prasad and Radhakrishnan .. .. .. .. .. 60 13 The Prime Minister and His Secretariat .. .. .. .. .. 65 14 The Prime Minister's House .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 70 15 Use ofAirForceAircraft bythe PM .. .. .. .. .. .. 73 16 Rafi Ahmed Kidwai .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 76 17 Feroze Gandhi .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 80 18 The National Herald and Allied Papers .. .. .. .. .. 83 19 Nehru and the Press .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 86 20 Nehru's Sensitivity to his Surroundings .. .. .. .. .. 90 21 Nehru's Attitude to Money .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 95 22 G. D. Birla .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 100 23 Nehru and Alcoholic Drinks .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 104 24 Sarojini Naidu .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . -

Calcutta Notebook Shoummo You Got Blood on Yo' Face You Big Disgrace Wavin' Your Banner All Over the Place We Will We Will Rock You

Frontier Vol. 43, No. 41, April 24‐30, 2011 Calcutta Notebook Shoummo You got blood on yo' face You big disgrace Wavin' your banner all over the place We will we will rock you. (lyrics from the song ‘We Will Rock you’ by Queen) Kolkata was important in 1969 for the first Rajdhani Express in the country, to speed to the metropolis on 1 March from New Delhi. The second United Front government of leftists and turncoat Congressmen was then in power. Foundation stone of the first underground railway in the country was laid on 29 December 1972 in this city by Indira Gandhi. The full 16.5 km underground stretch became operational in 1995 and even after 23 years since the laying of the foundation stone, it was the only of its kind in the country. In today's scam ridden milieu, this city's claim to fame was the first major post independence financial scam which had its roots in this city. Haridas Mundhra, a city trader duped Life Insurance Corporation of India to invest in the equity of a few bankrupt companies that he managed. The scam led to the resignation of T T Krishnamachari, the then finance minister, in 1958. Calcutta and Bengal has been on a slow gear since then and in 1985, Rajiv Gandhi ended up calling Kolkata a dying city. However, dying or otherwise, Calcutta and Bengal have been continuously exporting manpower of both the skilled and unskilled variety all across the country. Be it sweatshops in Kalbadevi that require finesse to turn gold into ornaments, software hubs in Bangalore and Hyderabad, construction industry in Kerala or dance bars in Mumbai and its suburbs, workforce from Bengal is ubiquitous. -

Lok Sabha Debates

)LIWK6HULHV9RO91R 7XHVGD\-XO\ $VDGKD 6DND /2.6$%+$'(%$7(6 6HFRQG6HVVLRQ )LIWK/RN6DEKD /2.6$%+$6(&5(7$5,$7 1(:'(/+, 3ULFH5H CONTENTS No, 32— Tnesday, July 6,1971jAsadha 15, 1893 (Saka) C olumns Obituary Reference 1—3 Oral Answers to Questions— ♦Starred Questions Nos 931, 932, 934 to 938, 940 to 943, 945, 946, 948 and 951 3—32 Written Answers to Questions - ♦Starred Questions Nos. 933, 939, 944, 947, 949, 950, and 952 to 960 33—41 Unstarrcd Questions Nos. 3946 to 3956, 3958 to 3976, 3978 to 4035, 4037 to 4052 and 4054 to 4103. 41—161 rolling Attention to Matter of Urgent Public Importance— Reported Supply of Arms to Pakistan by USSR and France 162— 179 Papers Laid on the Table 179-180 Demands for Grants, 1971 -72— 180—286 Ministry of Foreign Trade 180— 197 Shri L. N< Mishra 180—196 Ministry of Petroleum and Chemicals 197—286 Shri R.P. Das 199-203 Shri Chintamani Panigrahi 204—211 Shri Indrajit Gupta 211—218 Shri Sat Pal Kapur 218—224 Shri C. Ghittibabu 224—228 Shri B.V. Naik 228—231 Shri Dalbir Singh 231—237 Dr. Laxminarain Pandey 237—244 Shri Dhamankar 244—248 Shri Somchand Solanki 248—251 •The lign + marked above the name of a Member indicates that the question was actually on the floor of the Hou«* by that Mcntbrt. ( ii ) C olumns Shri Unnikrishnan .. 251—254 Shri M. Satyanarayan Rao .. 254—256 Shri Anantrao Patil .. 256—258 Shri P. K. Deo .. 258 -260 Shri S. R. Damani .. 260—263 Shri N.