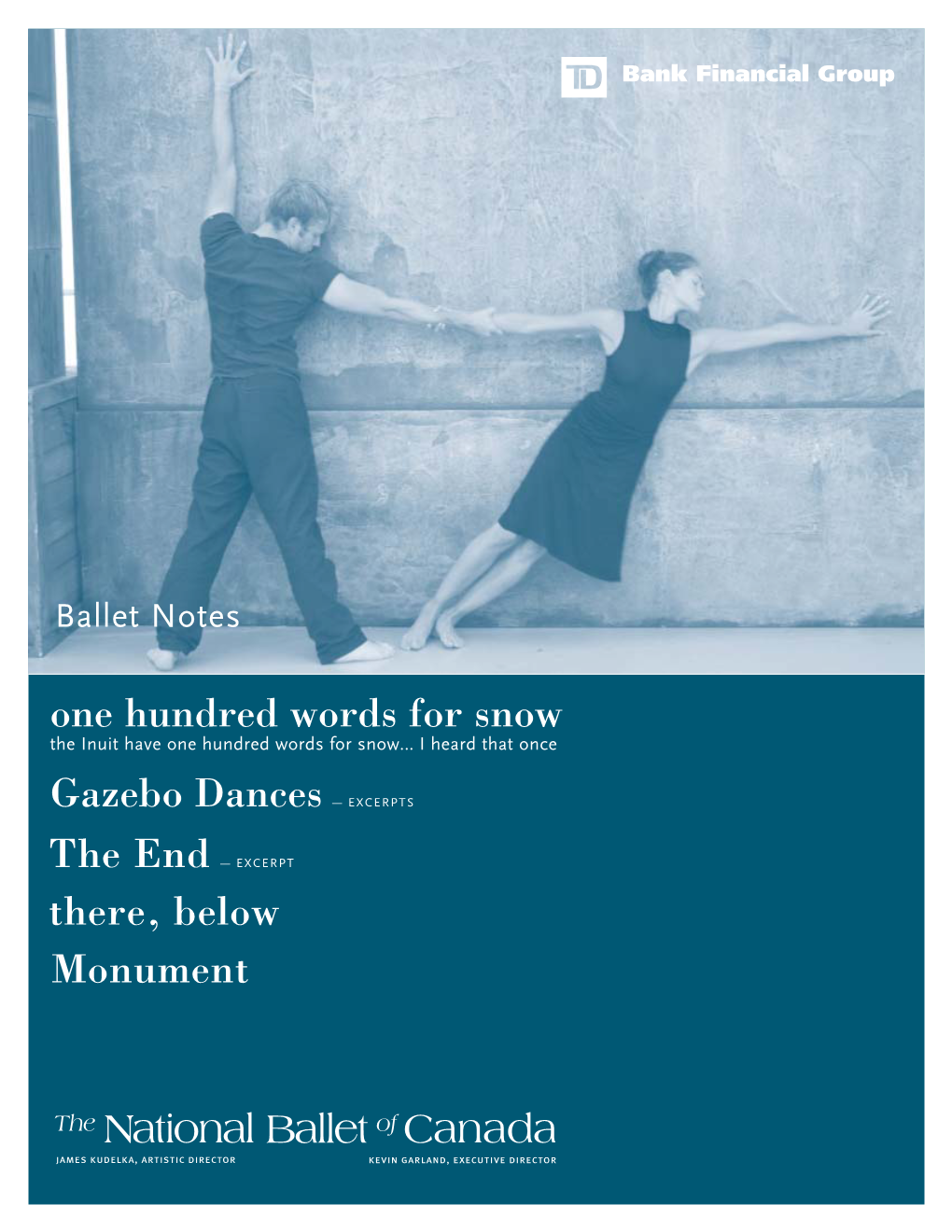

1338. Mixed Program Ballet Note

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nicolle Greenhood Major Paper FINAL.Pdf (4.901Mb)

DIVERSITY EN POINTE: MINIMIZING DISCRIMINATORY HIRING PRACTICES TO INCREASE BALLET’S CULTURAL RELEVANCE IN AMERICA Nicolle Mitchell Greenhood Major paper submitted to the faculty of Goucher College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Arts Administration 2016 Abstract Title of Thesis: DIVERSITY EN POINTE: MINIMIZING DISCRIMINATORY HIRING PRACTICES TO INCREASE BALLET’S CULTURAL RELEVANCE IN AMERICA Degree Candidate: Nicolle Mitchell Greenhood Degree and Year: Master of Arts in Arts Administration, 2016 Major Paper Directed by: Michael Crowley, M.A. Welsh Center for Graduate and Professional Studies Goucher College Ballet was established as a performing art form in fifteenth century French and Italian courts. Current American ballet stems from the vision of choreographer George Balanchine, who set ballet standards through his educational institution, School of American Ballet, and dance company, New York City Ballet. These organizations are currently the largest-budget performing company and training facility in the United States, and, along with other major US ballet companies, have adopted Balanchine’s preference for ultra thin, light skinned, young, heteronormative dancers. Due to their financial stability and power, these dance companies set the standard for ballet in America, making it difficult for dancers who do not fit these narrow characteristics to succeed and thrive in the field. The ballet field must adapt to an increasingly diverse society while upholding artistic integrity to the art form’s values. Those who live in America make up a heterogeneous community with a blend of worldwide cultures, but ballet has been slow to focus on diversity in company rosters. -

Madame Ballet' As Establish a Perth-Based Ballet Company Western Australian Author Ffion Murphy As a Result of Those Who Had Prepared the Ground for Her

Michelle Potter reveals how Bousloff, whose youth had been lived out Russian dancer Kira Bousloff boldly of a suitcase as she travelled the world as a dancer with the Ballets Russescompanies created an environment for dance of Colonel de Basil, decided to remain in to flourish in Western Australia Australia in 1939 at the end of a tour by the Covent Garden Russian Ballet. She recalls When I came to the airport here in little Perth, that decision in an oral history interview at the end of the world, I put my feet on the recorded for the National Library in 1990: ground, I looked around, and I said loudly and strongly 'That's where I'm going to live and I was sitting in my hotel room in Melbourne that's where I'm going to die'. on my own and I had a strong feeling that my father (who had died many years ago) -Kira Bousloff touched my shoulder. It was a physical feeling practically. Then I had suddenly this strong ira Bousloff, or Kira Abricossova as feeling that I had to stay in Australia. So she was known during her early without even thinking twice (of course, you see, Kperforming career, was the founder of I'm a bit queer, eccentric, but that's the truth, the West Australian Ballet, one of Australia's that's what happened) I ran down the stairs and earliest state-based ballet companies-the rang up ... a very good friend and I said, 'I want first, in fact, to call itself a state company. -

Project Faust

PUBLISHER FEARLESS DESIGNS, INC. March 2018 EDITOR KAY TULL MANAGING EDITOR AGGIE KEEFE CREATIVE DIRECTOR FROM THE DIRECTOR ................................................................... 4 JEFF TULL PROGRAM HE EYOND DESIGN T B ........................................................................ 7 KAY & JEFF TULL REQUIEM .......................................................................... 8 PROJECT FAUST .................................................................. 9 PRODUCTION BIOGRAPHIES ....................................................................... 21 AGGIE KEEFE ARTISTS OF THE COMPANY...................................................... 34 STAFF & SUPPORT ................................................................ 38 SALES MANAGER MICHELLE BAIR THEATRE SERVICES ..................................................................... 54 PRINTING CLARK & RIGGS PRINTING THEATRE INFORMATION The Kentucky Center (Whitney Hall, Bomhard Theater, Clark-Todd Hall, MeX Theater, 501 West Main Street; and Brown Theatre, 315 W. Broadway). Tickets: The Kentucky Center Box Office, 502.584.7777 or 1.800.775.7777. Reserve wheelchair seating or hearing devices at time of ticket purchase. © COPYRIGHT 2018 LOOK AROUND YOU RIGHT NOW. IF THE PEOPLE YOU SEE LOOK LIKE POTENTIAL FEARLESS DESIGNS, INC. CUSTOMERS AND CLIENTS, YOU SHOULD BE ADVERTISING IN OUR PROGRAM REPRODUCTION IN GUIDES! OUR ADVERTISERS NOT ONLY GET THE BENEFIT OF REACHING A LARGE, WHOLE OR PART CAPTIVE, AFFLUENT AND EDUCATED DEMOGRAPHIC, BUT THEY ALSO SUPPORT -

The Australian Ballet 1 2 Swan Lake Melbourne 23 September– 1 October

THE AUSTRALIAN BALLET 1 2 SWAN LAKE MELBOURNE 23 SEPTEMBER– 1 OCTOBER SYDNEY 2–21 DECEMBER Cover: Dimity Azoury. Photography Justin Rider Above: Leanne Stojmenov. Photography Branco Gaica Luke Ingham and Miwako Kubota. Photography Branco Gaica 4 COPPÉLIA NOTE FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Dame Peggy van Praagh’s fingerprints are on everything we do at The Australian Ballet. How lucky we are to have been founded by such a visionary woman, and to live with the bounty of her legacy every day. Nowhere is this legacy more evident than in her glorious production of Coppélia, which she created for the company in 1979 with two other magnificent artists: director George Ogilvie and designer Kristian Fredrikson. It was her parting gift to the company and it remains a jewel in the crown of our classical repertoire. Dame Peggy was a renowned Swanilda, and this was her second production of Coppélia. Her first was for the Borovansky Ballet in 1960; it was performed as part of The Australian Ballet’s first season in 1962, and was revived in subsequent years. When Dame Peggy returned to The Australian Ballet from retirement in 1978 she began to prepare this new production, which was to be her last. It is a timeless classic, and I am sure it will be performed well into the company’s future. Dame Peggy and Kristian are no longer with us, but in 2016 we had the great pleasure of welcoming George Ogilvie back to the company to oversee the staging of this production. George and Dame Peggy delved into the original Hoffmann story, layering this production with such depth of character and theatricality. -

Dance Brochure

Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Limited Dance 2006 Edition Also see www.boosey.com/downloads/dance06icolour.pdf Figure drawings for a relief mural by Ivor Abrahams (courtesy Bernard Jacobson Gallery) The Boosey & Hawkes catalogue contains many of the most significant and popular scores in the dance repertoire, including original ballets (see below) and concert works which have received highly successful choreographies (see page 9). To hear some of the music, a free CD sampler is available upon request. Works written as ballets composer work, duration and scoring background details Andriessen Odyssey 75’ Collaboration between Beppie Blankert and Louis Andriessen 4 female singers—kbd sampler based on Homer’s Odyssey and James Joyce’s Ulysses. Inspired by a fascination with sensuality and detachment, the ballet brings together the ancient, the old and the new. Original choreography performed with four singers, three dancers and one actress. Argento The Resurrection of Don Juan 45’ Ballet in one act to a scenario by Richard Hart, premiered in 1955. 2(II=picc).2.2.2—4.2.2.1—timp.perc:cyms/tgl/BD/SD/tamb— harp—strings Bernstein The Dybbuk 50’ First choreographed by Jerome Robbins for New York City Ballet 3.3.4.3—4.3.3.1—timp.perc(3)—harp—pft—strings—baritone in 1974. It is a ritualistic dancework drawing upon Shul Ansky’s and bass soli famous play, Jewish folk traditions in general and the mystical symbolism of the kabbalah. The Robbins Dybbuk invites revival, but new choreographies may be created using a different title. Bernstein Facsimile 19’ A ‘choreographic essay’ dedicated to Jerome Robbins and 2(II=picc).2.2(=Ebcl).2—4.2.crt.2.1—timp.perc(2)— first staged at the Broadway Theatre in New York in 1946. -

Cinderella Resource Pack

CINDERELLA A BALLET BY DAVID NIXON OBE RESOURCE PACK Introduction This resource pack gives KS2 and KS3 teachers and pupils an insight into Northern Ballet’s Cinderella. It can be used as a preparatory resource before seeing the production, follow up work after seeing the production or as an introduction to Northern Ballet or ballet in general. Contents • The History of Cinderella • • Characters • • Story • • About Northern Ballet’s Cinderella • • Costumes • • Sets • • Music • • Creative Team • • Terminology • • Gallery • Click on the links on each page to Terminology is highlighted and can find out more (external websites). be found at the back of this pack. This resource pack was created in autumn 2019. Photos Bill Cooper, Riku Ito, Emma Kauldhar and Dolly Williams. Cinderella is a universal story which has been re-written and retold in many different countries and cultures around the world. The oldest account of the story is from China, dating back to the 9th century AD. The well-known classic fairy tale was written by Charles Perrault and published in France as Cendrillon in 1697. Cendrillon told the story of a virtuous girl, whose mother dies, resulting in her being treated inhumanely by her family. In the end she is rescued by magical love from her mother beyond the grave. Task: How many elements of the Cinderella story do you know? A Stepmother and two Stepsisters A ball which Cinderella is not allowed to attend A visit by a Fairy Godmother The History of Receiving glass slippers Being home by midnight Losing a glass slipper Cinderella A Prince searching for the girl that fits the slipper There are numerous films, books, ballets and pantomimes which tell the story of Cinderella, all with their own interpretation. -

The Australian Ballet with Berkeley Symphony in Graeme Murphy’S Swan Lake Music by Pyotr Il’Yich Tchaikovsky Swan Lake: Ballet in Four Acts , Op

Thursday, October 16, 2014, 8pm Friday, October 17, 2014, 8pm Saturday, October 18, 2014, 2pm & 8pm Sunday, October 19, 2014, 3pm Zellerbach Hall The Australian Ballet with Berkeley Symphony in Graeme Murphy’s Swan Lake Music by Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky Swan Lake: Ballet in Four Acts , Op. 20 (1875–1876) y b s u B ff e J David McAllister AM, Artistic Director Libby Christie, Executive Director Nicolette Fraillon, Music Director and Chief Conductor The Australian Ballet acknowledges the invaluable support of its Official Tour Partners, Qantas and News Corp. The Australian Ballet’s 2014 tour to the United States has been generously supported by the Talbot Family Foundation and by The Australian Ballet’s International Touring Fund. These performances are made possible, in part, by Corporate Sponsor U.S. Bank, and by Patron Sponsors Deborah and Bob Van Nest, and Anonymous. Cal Performances’ – season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. CAL PERFORMANCES 19 Cal Performances thanks for its support of our presentation of The Australian Ballet in Graeme Murphy’s Swan Lake. PLAYBILL PROGRAM Graeme Murphy’s Swan Lake Choreography Graeme Murphy Creative Associate Janet Vernon Music Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893): Swan Lake , Op. 20 (1875 –1876) Concept Graeme Murphy, Janet Vernon, and Kristian Fredrikson Set and Costume Design Kristian Fredrikson Original Lighting Design Damien Cooper PROGRAM Act I Scene I Prince Siegfried’s quarters Scene II Wedding festivities INTERMISSION Act II Scene I The sanatorium Scene II The lake INTERMISSION Act III An evening -

National Theatre Ballet School UNIFORM

THE NATIONAL THEATRE MELBOURNE THE NATIONAL THEATRE BALLET SCHOOL One of Australia's preeminent training institutions, the National Theatre Ballet School is distinguished as the fore-runner and longest-running of the country's dance schools. We are devoted to providing world class training, nurturing you through the next stage of your artistic development. The school is proudly led by Artistic Director Damian Smith, an inspirational dancer with more than 25 years' international experience with companies including Boston Ballet, Dutch National Ballet, Hong Kong Ballet, Hamburg Ballet, Ballet Du Nord and New York City Ballet. He joined the San Francisco Ballet in 1996, performing as Principal Dancer from 2001 until he joined the National Theatre Ballet School in 2018. The National Theatre Ballet School is famous for our professional training with a reputation for excellence that is proven year after year by ever-growing alumni of dancers pursuing successful careers in dance. We understand that a career in dance is physically rigorous and highly competitive. We also understand what it feels like to be passionate about the performing arts; our professionally trained and encouraging teachers are here to develop your skills, your confidence and your resilience. We shall provide the necessary training and support to help you fulfil your potential. Located in Melbourne's iconic National Theatre under the same roof as the Drama school, the Ballet school enables students to train in our beautiful heritage listed building and perform in the 800-seat theatre supported by our professional production and technical teams. And with the stunning St Kilda Beach just 5 minutes' walk away, you will be able to unwind and relax after an invigorating day in the rehearsal room. -

January 2020 Resident Choreographers

® Global Resident Choreographer Survey JANUARY 2020 Summary Dance Data Project® (DDP) has conducted an initial examination of resident choreographer positions globally within the ballet industry. DDP found that among the 116 international and U.S. ballet companies studied, a significant majority have hired men as resident choreographers. The study reveals that 37 of the 116 ballet companies surveyed globally employ resident choreographers. Twenty-eight of these 37 companies have placed exclusively men in this position (76%). DDP found that 22 of the 69 U.S. ballet companies surveyed employ resident choreographers. Sixteen of these 22 domestic companies have hired exclusively men in this position (73%). DDP also found that 15 of the 47 international ballet companies examined employ resident choreographers. Only 2 of these 15 companies have hired exclusively women (13%), although one international company employs four resident choreographers (1 woman, 3 men). © DDP 2020 Dance DATA Global Resident Project] Choreographer Survey Introduction A note about resident choreographers: The position of resident choreographer is one of the most secure opportunities for the otherwise freelance choreographer. The position offers a contract with a steady salary, the possibility of benefits, a group of dancers with whom to workshop, time, access to set, costume, lighting designers and a regular audience. Most ballet companies do not employ resident choreographers, given the expense of an additional employee and funding regular commissions. Quite often, an artistic director serves as a de facto resident choreographer, regularly creating for the company and producing new works. DDP reviewed as many prominent dance publications1 as possible and consulted several leaders of ballet companies and dance venues in the U.S. -

Alexander Ekman

CONTENTS INTRODUCTION What is a Student Matinee? 3 Learning Outcomes 5 TEKS Addressed 6 PRE-PERFORMANCE INFORMATION Attending A Ballet Performance 16 Rock, Roll & Tutus: Program 17 What’s That?!: Mixed Repertory 19 Meet the Creators: Choreographers & Composers 20 Rock, Roll & Tutus: Tutu Exhibit 28 It Takes Teamwork: Pas de Deux 29 My Predictions: Pre-Performance Activity 30 POST-PERFORMANCE ACTIVITIES Dancing Shapes 32 Found Sound 34 Show What You Know 35 Word Search/Crossword 36 Review & Reflect/Discussion Questions 39 LEARN MORE! All About Arms 41 All About Legs 42 Why Do They Wear That? 43 Houston Ballet: A Brief History 44 Glossary 45 2 WHAT IS A STUDENT MATINEE? Student Matinees are full length performances by Houston Ballet with live orchestra held during school hours. Your students experience these professional performances with interactive intermissions at significantly discounted ticket prices. This study guide has information and activities for before and after the performance that are intended to extend the learning experience. WHAT TO EXPECT Arrival and Departure As a result of the damage from Hurricane Harvey, Houston Ballet’s performance home, the Wortham Theater, has been closed until further notice. Consequently, Houston Ballet is on a “Hometown Tour” for its 2017-18 season. The Rock, Roll & Tutus Student Matinee will be held in Hall A at: George R. Brown Convention Center 1001 Avenida De Las Americas Houston, TX 77010. Your bus will drop off and pick up students in the bus depot in theNorth Garage on Rusk Street. 3 If you are arriving by bus: You will enter bus parking on the north side of Rusk Street. -

Our Next Historic Step! a Message from Our Patrons, Dr Ken Michael AC, Governor of Western Australia and Mrs Julie Michael

WEST AUSTRALIAN BALLET His Majesty’s Theatre 825 Hay Street Perth WA 6000 PO Box 7228 Cloisters Square Perth WA 6850 PRINCIpaL PARTNER T: (08) 9214 0707 F: (08) 9481 0710 [email protected] waballet.com.au OUR NEXT HISTORIC STEP! A MESSAGE FROM OUR PATRONS, DR KEN MICHAEL AC, GOVERNOR OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA AND MRS JULIE MICHAEL. West Australian Ballet has just celebrated the significant milestone of its 40th anniversary as the State Ballet Company. Much has been achieved in the history of the Company, including most recently with the support of the Western Australian government, a new vision that will see an augmented ensemble of 32 dancers and 8 WEST AUSTRALIAN BALLET young artists. MISSION & VISION A unique opportunity has now presented itself to create a State ballet centre in Maylands, a new home to replace the Company’s present accommodation at His Majesty’s Theatre. The challenge now is to raise the funds required to refurbish the building as a world class ballet training and rehearsal facility. As joint Patrons, Julie and To present outstanding classical and contemporary dance for the enjoyment, I hope that you will fully support this exciting initiative and contribute all that you can to the Company’s Capital entertainment and enrichment of our communities. Campaign. We commend this project to you whole heartedly. To be a world class ballet company for the benefit of all Western Australians A MESSAGE FROM THE HON JOHN DAY MLA, MINISTER FOR CULTURE AND THE ARTS. and the pre-eminent dance company in the Asia Pacific region. -

2016 Annual Report

2016 Annual Report PRINCIPAL PARTNER Contents section one COMPANY OVERVIEW 3 REPORTS 4 Chair’s Report 5 Artistic Director’s Report 6 Executive Director’s Report 8 KEY FOCUS AREAS 9 1. Artistry 10 2. Access 13 3. Activation 15 HIGHLIGHTS 19 International Touring 20 KEY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS 21 1. Seasons and Repertoire 22 2. Artistic Vibrancy 26 3. Access 26 4. Performances and Attendance 27 5. Income 29 DIRECTORS, SUPPORTERS AND COMPANY DETAILS 31 Board Directors 32 Committees 35 Private Giving 36 Corporate Partners 38 Company Details 39 section two 2016 FINANCIAL REPORT 41 134 Whatley Crescent, Maylands WA 6051 PO Box 604, Maylands WA 6931 P: +61 8 9214 0707 F: +61 8 9481 0710 [email protected] waballet.com.au ABN: 55 023 843 043 Cover: Photo Sergey Pevnev. SECTION ONE Company PATRON Her Excellency the Hon. Kerry Sanderson AC, Overview Governor of Western Australia PRIVATE GIVING PATRON Mrs Alexandra Burt PROFILE West Australian Ballet (WAB) is the State ballet company for Western Australia, based in Perth, and is proud of its heritage as Australia’s first ballet company – established in 1952. WAB boasts a full time professional troupe of dancers, and presents a diverse repertoire of full-length ballets and modern repertoire locally, nationally and internationally. MISSION To enrich people’s lives through dance. VISION To be recognised for exceptional ballet experiences and leadership within our communities, locally and globally. GOALS West Australian Ballet will achieve its VISION by: • Positioning the company as Australia’s most