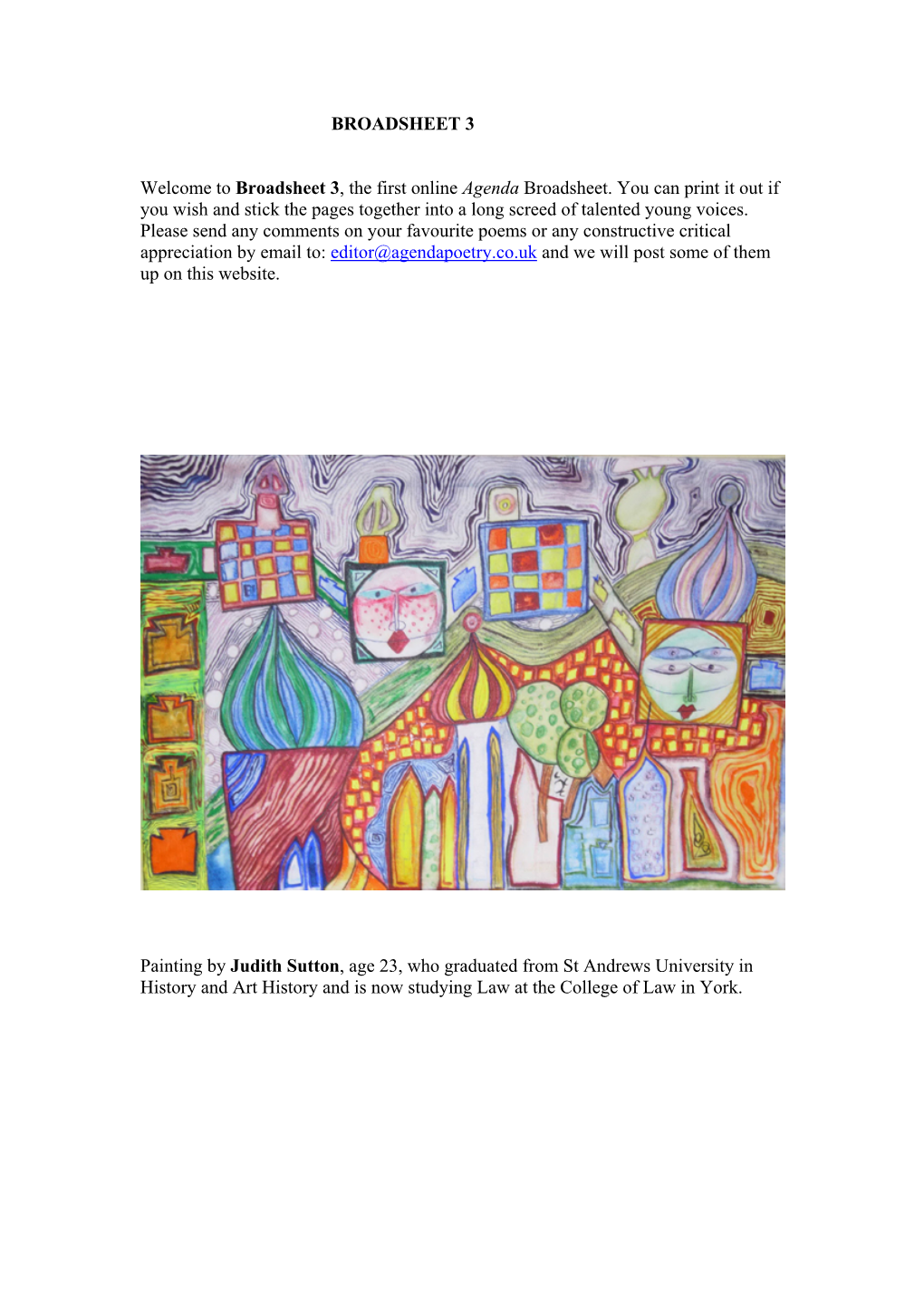

Broadsheet 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Only Imagine

I CAN ONLY IMAGINE I CAN A Memoir ONLY IMAGINE Bart Millard a memoir With Robert Noland Bart Millard with robert noland Imagine_A.indd 7 10/3/17 10:11 AM Appendix 1 YOUR IDENTITY IN CHRIST My mentor, Rusty Kennedy, was integral in discipling me in my walk with Christ. He gave me these seventy- five verses and state- ments while I was unpacking my past and starting to understand who I truly am in Jesus. Ever since then, I have carried these close to my heart. I pray these will minister to you the way they have to me so that you, too, can understand that in Christ, you are free indeed! 1. John 1:12—I am a child of God. 2. John 15:1–5—I am a part of the true vine, a channel (branch) of His life. 3. John 15:15—I am Christ’s friend. 4. John 15:16—I am chosen and appointed by Christ to bear His fruit. 5. Acts 1:8—I am a personal witness of Christ for Christ. 6. Romans 3:24—I have been justified and redeemed. 7. Romans 5:1—I have been justified (completely forgiven and made righteous) and am at peace with God. 8. Romans 6:1–6—I died with Christ and died to the power of sin’s rule in my life. APPENDIX 1 9. Romans 6:7—I have been freed from sin’s power over me. 10. Romans 6:18—I am a slave of righteousness. 11. Romans 6:22—I am enslaved to God. -

Praise & Worship from Moody Radio

Praise & Worship from Moody Radio 04/28/15 Tuesday 12 A (CT) Air Time (CT) Title Artist Album 12:00:10 AM Hold Me Jesus Big Daddy Weave Every Time I Breathe (2006) 12:03:59 AM Do Something Matthew West Into The Light 12:07:59 AM Wonderful Merciful Savior Selah Press On (2001) 12:12:20 AM Jesus Loves Me Chris Tomlin Love Ran Red (2014) 12:15:45 AM Crown Him With Many Crowns Michael W. Smith/Anointed I'll Lead You Home (1995) 12:21:51 AM Gloria Todd Agnew Need (2009) 12:24:36 AM Glory Phil Wickham The Ascension (2013) 12:27:47 AM Do Everything Steven Curtis Chapman Do Everything (2011) 12:31:29 AM O Love Of God Laura Story God Of Every Story (2013) 12:34:26 AM Hear My Worship Jaime Jamgochian Reason To Live (2006) 12:37:45 AM Broken Together Casting Crowns Thrive (2014) 12:42:04 AM Love Has Come Mark Schultz Come Alive (2009) 12:45:49 AM Reach Beyond Phil Stacey/Chris August Single (2015) 12:51:46 AM He Knows Your Name Denver & the Mile High Orches EP 12:55:16 AM More Than Conquerors Rend Collective The Art Of Celebration (2014) Praise & Worship from Moody Radio 04/28/15 Tuesday 1 A (CT) Air Time (CT) Title Artist Album 1:00:08 AM You Are My All In All Nichole Nordeman WOW Worship: Yellow (2003) 1:03:59 AM How Can It Be Lauren Daigle How Can It Be (2014) 1:08:12 AM Truth Calvin Nowell Start Somewhere 1:11:57 AM The One Aaron Shust Morning Rises (2013) 1:15:52 AM Great Is Thy Faithfulness Avalon Faith: A Hymns Collection (2006) 1:21:50 AM Beyond Me Toby Mac TBA (2015) 1:25:02 AM Jesus, You Are Beautiful Cece Winans Throne Room 1:29:53 AM No Turning Back Brandon Heath TBA (2015) 1:32:59 AM My God Point of Grace Steady On 1:37:28 AM Let Them See You JJ Weeks Band All Over The World (2009) 1:40:46 AM Yours Steven Curtis Chapman This Moment 1:45:28 AM Burn Bright Natalie Grant Hurricane (2013) 1:51:42 AM Indescribable Chris Tomlin Arriving (2004) 1:55:27 AM Made New Lincoln Brewster Oxygen (2014) Praise & Worship from Moody Radio 04/28/15 Tuesday 2 A (CT) Air Time (CT) Title Artist Album 2:00:09 AM Beautiful MercyMe The Generous Mr. -

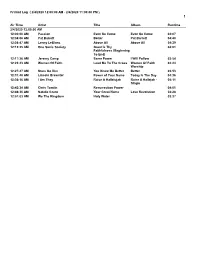

Printed Log ( 2/4/2020 12:00:00 AM - 2/4/2020 11:00:00 PM ) 1

Printed Log ( 2/4/2020 12:00:00 AM - 2/4/2020 11:00:00 PM ) 1 Air Time Artist Title Album Runtime 2/4/2020 12:00:00 AM 12:00:00 AMPassion Even So Come Even So Come 04:07 12:04:06 AM Pat Barrett Better Pat Barrett 04:40 12:08:47 AMLenny LeBlanc Above All Above All 04:39 12:13:25 AM One Sonic Society Great Is Thy 04:01 Faithfulness (Beginning To End) 12:17:26 AM Jeremy Camp Same Power I Will Follow 03:54 12:23:23 AMWomen Of Faith Lead Me To The Cross Women Of Faith 04:24 Worship 12:27:47 AM Stars Go Dim You Know Me Better Better 03:53 12:31:40 AMLincoln Brewster Power of Your Name Today Is The Day 04:36 12:36:16 AMI Am They Raise A Hallelujah Raise A Hallejah - 04:11 Single 12:42:34 AM Chris Tomlin Resurrection Power 04:01 12:46:35 AM Natalie Grant Your Great Name Love Revolution 04:28 12:51:03 AM We The Kingdom Holy Water 03:37 Printed Log ( 2/4/2020 12:00:00 AM - 2/4/2020 11:00:00 PM ) 2 Air Time Artist Title Album Runtime 2/4/2020 1:00:00 AM 1:00:00 AM The Museum My Help Comes From Let Love Win 03:28 The Lord 1:03:27 AMCody Carnes Nothing Else Nothing Else - Single 05:24 1:08:52 AMSteve Green Majesty (Here I Am) Always 05:35 1:14:27 AMTenth Avenue North I Have This Hope Followers 03:19 1:17:47 AMWe Are Messengers Magnify We Are Messengers 03:09 1:23:00 AMTodd Agnew Gloria Need 02:43 1:25:43 AM Leeland Waymaker 05:05 1:30:48 AMNicol Sponberg No Not One Awake My Soul 02:59 1:33:47 AMMack Brock I Am Loved Covered 05:31 1:39:18 AMTodd Agnew Gloria Need 02:43 1:44:07 AMHillsong United Not Today Wonder 03:43 1:47:49 AM Blended Worship Holy -

1/13/2021 12:00:00 AM 05:14 Darlene Zschech 12

Printed Log ( 1/13/2021 Wednesday at 12:00 AM - 1/13/2021 Wednesday at 11:59 PM ) 1 Air Time Artist Title Album Runtime 1/13/2021 12:00:00 AM 12:00:00 AM Darlene Zschech God So Loved You Are My World 05:14 12:05:15 AM Pat Barrett Better Pat Barrett 04:47 12:10:02 AM Passion The Lord Our God Passion: Let The Future 03:49 Begin 12:13:52 AM Matt Redman Let Everything That Intimacy 02:43 Has Breath 12:16:34 AM Kari Jobe The Blessing The Blessing 04:17 12:23:35 AM Vertical Worship Yes I Will Bright Faith Bold 03:32 Future 12:27:07 AM Todd Agnew Gloria Need 02:43 12:29:52 AM Red Rocks Worship Breakthrough Breakthrough (Single 03:56 Version) 12:33:48 AM Michael W. Smith The Stand Stand 02:49 12:36:38 AM Mack Brock I Am Loved Covered 05:31 12:44:46 AM Natalie Grant King of the World Be One 03:21 12:48:07 AM Michael W. Smith Waymaker Way Maker 03:55 12:52:01 AM Chris Renzema Springtime Springtime 04:06 Printed Log ( 1/13/2021 Wednesday at 12:00 AM - 1/13/2021 Wednesday at 11:59 PM ) 2 Air Time Artist Title Album Runtime 1/13/2021 1:00:00 AM 1:00:00 AM Darlene Zschech At The Cross At The Foot of the 04:14 Cross 1:04:21 AM Chris Tomlin Resurrection Power Holy Roar 04:01 1:08:22 AM SEU Worship Fire in My Bones Brand New Worship 03:20 1:11:42 AM Selah Hosanna You Deliver Me 04:03 1:15:45 AM Jonathan Traylor You Get The Glory The Unknown 03:47 1:22:19 AM Shannon Wexelberg Count It All Joy Better Than Life 04:12 1:26:32 AM Elevation Worship Graves Into Gardens Graves into Gardens 04:10 1:30:41 AM Pat Barrett Build My Life Build My Life - EP 04:16 1:34:57 -

2010Pvcatalogindexpages837-880.Pdf

index 838 INDEX A-Z of Classical Music .............................................. 405 Acoustic Rock Guitar Songs for Dummies ................ 490 All American Boogie Woogie .................................... 437 Aaberg, Philip – Piano Solos ...................................... 77 Acoustic Rock Hits – Easy Guitar.............................. 490 All American Folk .................................................... 426 AB Real Book ............................................................. 46 Across the Universe – All American Rejects – Move Along ............................ 80 Abair, Mindi – Collection – Music from the Motion Picture – P/V/G ............ 275 All Around the U.S.A. – P/V/G ........................... 484, 562 Saxophone Artist Transcriptions .......................... 77 Across the Universe – Music from the Motion Picture – All Creatures of Our God and King ........................... 784 ABBA – Best of ........................................................... 77 Original Keys for Singers ................................... 611 All Music Guide to Classical Music ........................... 414 ABBA – Gold: Greatest Hits ......................................... 77 Actor’s Songbook .....................................268, 562, 581 All Shook Up – Vocal Selections ............................... 264 ABBA – Pro Vocal Women’s Edition ................. 360, 614 Adams, Bryan – Anthology ......................................... 78 All That Remains – Fall of Ideals ................................ 80 Above All – Phillip -

Unit 6 Using Maps

Bright star -English for grade 7 –second term 2018-Mr:Mohammed lotfy 0503437147 UNIT 6 USING MAPS عربة كارو carriage منذ زمن For ages كاتالوج catalogue وسط المدينة City center يغير الى change to يغير change يغير من اجل change for اختصار abbreviation بوصلة compass يصل الى arrive at بالتاكيد definitely رائد فضاء astronaut قارب صغير astronomy dhow اتجاة direction خلف behind يقود عائدا drive back مكان ركن السيارة car park Read the conversations and answer the questions: ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- Ahmed: Hey, Saif. I haven’t seen you for ages. Saif: Ahmed. Good to hear from you. Ahmed: Where are you? At home? Saif: Now? No, I’m in the city centre. Ahmed: What are you doing? Saif: I’m in the bank. You know we’re going to England next week? So, I’ve come here to change some money. Conversation 2 Yousif: Mohammed? It’s me. Where are you? Mohammed: Hi Yousif. I’m at the police academy. Yousif: Really? I thought you were going to the cinema. Mohammed: Yes, I am later. You know my cousin Safwan? I came here to visit him. He’s training to be a police officer. We’re going to the cinema this evening. Bright star -English for grade 7 –second term 2018-Mr:Mohammed lotfy 0503437147 Conversation 3 Murad: Hi Khaled. Khaled: Hi, Murad. How are you? Murad: Fine thanks. It’s loud there - are you in a metro station? Khaled: No, I’m in the mall. Murad: What are you doing? Shopping again? Khaled: Yes. I need a new watch, so I came here to buy one. -

CEFC Update for 11.17.17

C O M M U N I T Y E V A N G E L I C A L F R E E C H U R C H W E E K L Y N E W S L E T T E R N O V E M B E R 1 7 , 2 0 1 7 CEVOANGMELICMAL FUREEN CHIUTRCYH P U R S U I N G G O D \ \ L O V I N G P E O P L E \ \ D E V E L O P I N G D I S C I P L E M A K E R S THIS WEEK'S NEWS - A community Thanksgiving service will be held at Westview Methodist Church this Sunday Community at 6:30 pm. All are encouraged to attend. There will be fellowship following the service, so please bring a pie to share. Those who attend are also encouraged to bring a Thanksgiving Service canned good item to donate to the local Food Pantry. Westview Methodist Sunday, 6:30pm - 180° youth group will not be meeting next Wednesday, November 22 due to Thanksgiving. It will resume for a game night (board games, large group games, etc.) on the following Wednesday, November 29th! All 7th-12th graders are welcome to join us! Bring friends and a few snacks to share! - The church office will be closed on November 23-24 for Thanksgiving. Regular office hours will resume the following Tuesday, November 28th. Membership Class Dec. 10 - A new small group bible study is starting on Tuesday, November 28th at 7:00 pm at Les & 12pm-2pm Georgia John's home. -

“God with Us God With

PARTITURA PARA BATERIA DE: Por: Anderson Cleiton Rodrigues “GOD WITH US” 12/2012 BATERA CENTER- SBO/SP. MERCY A banda " MERCY ME " M E A banda cristã norte americana " MercyMe" , foi criada em 1994 por Bart Millard (voz), James Bryson (teclados), Nathan Cochran (baixo), Michael Scheuchzer e Barry Graul (guitarra), Robin Shaffer (bateria). Posteriormente se juntou a banda o guitarrista Barry Graul. A banda ganhou notoriedade, com o single "I Can Only Imagine" do álbum Almost There, certificado com dupla platina, além de outros álbuns com certificado ouro. Mercy M e já emplacou também diversos GMA Dove Awards. Entre suas músicas podemos destacar: " I Can Only Imagine", "Spoken For" e "Word of God Speak", "Here With Me", "In the Blink of an Eye", "So Long Self", "Coming U p To Breathe" e "Hold Fast", "God With Us", "You Reign" e "Finally Home". Discografia: Pleased To Meet You (1997), Traces Of Rain, Vol. 1 & 2 (1997), The Need (1998), The Worship Project (1999), Look (2000), Almost There (2001), Spoken For (2002), Undone (2004), The Christimas Sessions (2005), Coming U p to Breathe (2006), Coming Up to Breathe Acoustic (2007), All That Is Within Me (2007), The Generous M r. Lovewell (2010), The Hurt & The Healer (2012). " All That Is Within Me" (2007) A música " GOD WITH US " A canção é a faixa de número 4 do álbum " All That Is Within Me" de 2007, o sexto da banda. O disco vendeu mais de 84 m il cópias somente na primeira semana de seu lançamento. Músicos: Jim Bryson (Piano, teclados) Nathan Cochran (Baixo) Baterista Robby Shaffer Eric Darken (Percussão) Barry Graul (Guitarra) Mike Haynes (Trompete) Bart Millard (Vocal) Mike Scheuchzer (Guitarra) Robby Shaffer (Bateria). -

Shelf-Sorted Parish Library Website Inventory March, 2016.Xls 3/15/16 JOSEPH's COAT of MANY COLORS BRILL, MARLENE 1992 2002.00 BOOK HARD CHILD BIBLE STORIES FAMILY

COPY DATE RIGHT ACQ'D TITLE AUTHOR MEDIA SHELF SUBJECT 1 SUBJECT 2 YOUR MARRIAGE PART 3: CAN LOVE CONQUER ALL? (MARRIAGE PREP SERIES) LIGUORI PUBLICATIONS 1989 2002.00 VHS MEDIA MARRIAGE BLESSED ARE THOSE WHO MOURN: COMFORTING CATHOLICS IN THEIR TIME OF GRIEF SPENCER, GLENN M., JR. 1999 2002.00 BOOK SOFT BEREAVE-ADULT GRIEF CATHOLIC HERITAGE AFTER THE DARKEST HOUR THE SUN WILL SHINE AGAIN MEHREN, ELIZABETH 2010.09 BOOK SOFT BEREAVE-ADULT GRIEF COPING HOW TO SURVIVE THE LOSS OF A CHILD SANDERS, CATHERINE PHD 2010.09 BOOK SOFT BEREAVE-ADULT GRIEF COPING TOWARD PEACE: PRAYERS FOR THE WIDOWED GORDON, BEVERLY S. 1990 2002.00 BOOK SOFT BEREAVE-ADULT GRIEF INSPIRATION SURVIVAL HANDBOOK FOR WIDOWS: (AND FOR RELATIVES & FRIENDS WHO WANT… LOEWINSOHN, RUTH JEAN 1984 2002.00 BOOK SOFT BEREAVE-ADULT GRIEF JESUS EMPTY CRADLE, BROKEN HEART DAVIS, DEBORAH L. PHD 2010.09 BOOK SOFT BEREAVE-ADULT GRIEF MAPS WATCHING MY FRIEND DIE: THE HONEST DEATH OF BOB SCHWARTZ HARE, MARK 2005 2005.07 BOOK SOFT BEREAVE-ADULT GRIEF HOW TO GO ON LIVING WHEN SOMEONE YOU LOVE DIES RANDO, THERESE A., PH.D. 1988 2004.05 BOOK SOFT BEREAVE-ADULT GRIEF YEAR OF MAGICAL THINKING, THE DIDION, JOAN 2006 2008.12 BOOK SOFT BEREAVE-ADULT GRIEF HEALING THE GREATEST HURT LINN, DENNIS & MATTHEW; FABRICANT,SHEILA 1985 2014.04 BOOK SOFT BEREAVE-ADULT GRIEF WHEN HELLO MEANS GOODBYE SCHWIEBERT, PAT, RN 1993 2015.01 BOOK SOFT BEREAVE-ADULT GRIEF RHYTHMS OF LIFE & DEATH, THE: COMFORT FOR THOSE WHO MOURN JORDANS, LESLEY 2002 2015.05 BOOK SOFT BEREAVE-ADULT GRIEF LIVING THROUGH MOURNING: FINDING -

February-2021-Books-Bibles-Music

february Releases Brandon Lake - House of Miracles (Live) 2CD Description For Brandon Lake, ‘House of Miracles (Live)’ is much more than an album, it’s the prayer of his life. His prayer is that every home in the world would become a house of miracles. Every heart is a hosting place of the Spirit of God, intricately designed to experience miracles. The songs were written to be conduits of hope for every person who listens. Compiled of some of the best songs from the studio album as well as some new ones, the live album also features many special guests. Brandon Lake is a songwriter and worship leader with the Bethel Music Collective and a worship pastor at Seacoast Church in South Carolina. Brandon is known for his song “This Is A Move,” written with Tasha Cobbs — a song that won a 2019 GMA Dove Award. Brandon Lake’s single “We Praise You” is featured on Bethel Music’s ‘Revival In The Air’ album. Track Listing: ‘House of Miracles (Live)’ Song 01. Running To The Light 02. Son Of Heaven (feat. dante Bowe & Matt Mayer) 03. Just Like Heaven 04. Gratitude 05. House of Miracles 06. House of Miracles (Prayer)[feat. Silverberg] 07. Show Me Your Glory (feat. Leeland) 08. When The Glory In The Room (feat. Leeland) 10. Lost In Your Love (feat. Sarah Reeves) Click link to play song: https://youtu.be/g2wzlqFwQnM 11. I Need A Ghost (feat. Dante Bowe) Title: House of Miracles (Live) 2CD Also Available: Artist: Brandon Lake Price: £12.99* Title: House of Miracles CD Title: Revival’s In The Air 2CD Product Code: 611851679910 Artist: Brandon Lake Artist: Bethel Music Product Code: 671072650310 Product Code: 671072649994 Format: 2CD Price: £9.99* Price: £12.99* Genre: Live Worship Distribution: UK & Europe FEBRUARY Available *All prices correct at time of going to press. -

Lochs and Loch Fishing

PART II. PRACTICAL LOCH FISHING. CHAPTER XIV. The Evolution of Loch Fishing : A History of Negatives. Herodotus with that charmingly simple faith in human credulity, which always distinguishes the true historian, describes in a certain part of his marvellous work a primitive, but none the less perfect, kind of fly- fishing practised in the remote period with which he is dealing by certain of the dwellers in that land of marvels—Africa. On translating, whether by the aid of a crib or otherwise, this portion of the works of the father of history, the average schoolboy who' knows anything about rods, other than the kind advertised by Solomon, permits him- self the luxury of a chuckley and if a rude boy puts his tongue in his cheek, raises the digital finger of his right hand tO' his nose and by an exercise of his comparative faculties, that does him more credit than the facial and manual exercises first mentioned, dubs Herodotus the father, not merely of history, but of the fish story. Though this mention of fly-fishing by Herodotus may thus make the unskilful laugh, it has the effect of making the judicious think. The result of such con- templation usually is that Herodotus is hailed as a sort of Darwin of historical evolution, or in other words, as a very keen observer who' has noted many things that might have escaped the eye of one less richly endowed with what we now-a-days term the journalistic insight and intuition. Herodotus may not have seen all he says he saw, but seeing something resembling what he described, he grasped intuitively what the Scottish pundits would have termed, its " infinite potentiality " and evolved from his inner consciousness with the aid of a prophetic eye playing on a few isolated facts the theory and practice of fly-fishing as time was destined tO' perfect it* This dipping intO' the future a good deal further than the average * Other and equally ancient authorities could be quoted to the same effect—dubious save by implication. -

The Art of Being Human: a Textbook for Cultural Anthropology

Kansas State University Libraries New Prairie Press NPP eBooks Monographs 2018 The Art of Being Human: A Textbook for Cultural Anthropology Michael Wesch Kansas State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/ebooks Part of the Multicultural Psychology Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Wesch, Michael, "The Art of Being Human: A Textbook for Cultural Anthropology" (2018). NPP eBooks. 20. https://newprairiepress.org/ebooks/20 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Monographs at New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in NPP eBooks by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. student submissions at anth101.com Anthropology is the study of all humans in all times in all places. But it is so much more than that. “Anthropology“ requires strength, valor, and courage,” Nancy Scheper-Hughes noted. “Pierre Bourdieu called anthropology a combat sport, an extreme sport as well as a tough and rigorous discipline. … It teaches students not to be afraid of getting one’s hands dirty, to get down in the dirt, and to commit yourself, body and mind. Susan Sontag called anthropology a “heroic” profession.” WhatW is the payoff for this heroic journey? You will find ideas that can carry you across rivers of doubt and over mountains of fear to find the the light and life of places forgotten. Real anthropology cannot be contained in a book.