Lochs and Loch Fishing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Only Imagine

I CAN ONLY IMAGINE I CAN A Memoir ONLY IMAGINE Bart Millard a memoir With Robert Noland Bart Millard with robert noland Imagine_A.indd 7 10/3/17 10:11 AM Appendix 1 YOUR IDENTITY IN CHRIST My mentor, Rusty Kennedy, was integral in discipling me in my walk with Christ. He gave me these seventy- five verses and state- ments while I was unpacking my past and starting to understand who I truly am in Jesus. Ever since then, I have carried these close to my heart. I pray these will minister to you the way they have to me so that you, too, can understand that in Christ, you are free indeed! 1. John 1:12—I am a child of God. 2. John 15:1–5—I am a part of the true vine, a channel (branch) of His life. 3. John 15:15—I am Christ’s friend. 4. John 15:16—I am chosen and appointed by Christ to bear His fruit. 5. Acts 1:8—I am a personal witness of Christ for Christ. 6. Romans 3:24—I have been justified and redeemed. 7. Romans 5:1—I have been justified (completely forgiven and made righteous) and am at peace with God. 8. Romans 6:1–6—I died with Christ and died to the power of sin’s rule in my life. APPENDIX 1 9. Romans 6:7—I have been freed from sin’s power over me. 10. Romans 6:18—I am a slave of righteousness. 11. Romans 6:22—I am enslaved to God. -

Tayside Local Biodiversity Action Plan 2Nd Edition 2016-2026

Tayside Local Biodiversity Action Plan 2nd Edition 20162026 Incorporating the local authority areas of Angus and Perth & Kinross Every Action Counts! Scottish Wildcat © Scottish Wildcat Action 2 Chairman’s Message Anyone glancing at this latest Biodiversity Action Plan for Tayside could be forgiven for feeling a little daunted at the scale of the tasks identified in the Actions. Indeed, the scale of what we need to do over the years ahead is large if we are to pass on to our future generations a land that is as rich and varied in all its forms of life as the one that we have inherited. The hope that we can rise to this challenge comes from the sheer goodwill of so many people and organisations willing to give their time and effort to look after our wildlife, whether it be found in the remoter hills or closer to home in our towns and villages. Great examples of what can be achieved when we work together with a little direction and thought applied can be found throughout the following pages. This Action Plan arrives at a time of great uncertainty, particularly in rural areas which have been so dependent on public funding for so much of our land use. Following the Brexit vote, we have to take the view that this must be an opportunity to improve on our delivery of so many of the tasks identified in this Plan and others which, if achieved, will improve the life of all of us along with all the many forms of life that we share this country with. -

Mesotrophic Lochs WW1

WATER AND WETLANDS Mesotrophic Lochs WW1 LORNE GILL / SNH LOCH LEVEN INTRODUCTION Mesotrophic lochs were identified by the UK Biodiversity Group as a key habitat of particular national importance that required specific work over and above that detailed in the standing open waters broad habitat plan. Much of the Standing Open Waters Habitat Action Plan therefore applies, but issues particularly relevant to mesotrophic lochs are examined here. 1 DEFINITION Mesotrophic lochs are defined either as those with a moderately rich plant nutrient environment, particularly nitrogen and phosphorus, or those having a range of submerged plant communities, principally NVC (National Vegetation Classification) types 5A and 5B. Type 5A is characterised by Shore-weed Littorella uniflora, Alternate flowered water milfoil Myriophyllum alterniflorum, Stoneworts Nitella spp., Small pondweed Potamogeton berchtoldii and Canadian pondweed Elodea canadensis, (an alien species). Type 5B is characterised by Floating pondweed Potamogeton natans, and White water lilies Nymphaea alba. However, lochs may be historically mesotrophic but have been subsequently changed to eutrophic by human activity. This type of loch has been included within this Plan as it may be possible in the long term to return them to a more natural nutrient status. CURRENT STATUS AND EXTENT OF HABITAT There are several mesotrophic lochs in Tayside, mainly located along the fringe of the uplands. These are listed under key sites, together with a brief assessment of their current status. It is apparent from the list that many lochs that were probably historically mesotrophic have now become eutrophic and others are threatened by nutrient enrichment. The Lowes chain of lochs between Dunkeld and Blairgowrie, which is of international significance, remains of high quality, but is threatened. -

Praise & Worship from Moody Radio

Praise & Worship from Moody Radio 04/28/15 Tuesday 12 A (CT) Air Time (CT) Title Artist Album 12:00:10 AM Hold Me Jesus Big Daddy Weave Every Time I Breathe (2006) 12:03:59 AM Do Something Matthew West Into The Light 12:07:59 AM Wonderful Merciful Savior Selah Press On (2001) 12:12:20 AM Jesus Loves Me Chris Tomlin Love Ran Red (2014) 12:15:45 AM Crown Him With Many Crowns Michael W. Smith/Anointed I'll Lead You Home (1995) 12:21:51 AM Gloria Todd Agnew Need (2009) 12:24:36 AM Glory Phil Wickham The Ascension (2013) 12:27:47 AM Do Everything Steven Curtis Chapman Do Everything (2011) 12:31:29 AM O Love Of God Laura Story God Of Every Story (2013) 12:34:26 AM Hear My Worship Jaime Jamgochian Reason To Live (2006) 12:37:45 AM Broken Together Casting Crowns Thrive (2014) 12:42:04 AM Love Has Come Mark Schultz Come Alive (2009) 12:45:49 AM Reach Beyond Phil Stacey/Chris August Single (2015) 12:51:46 AM He Knows Your Name Denver & the Mile High Orches EP 12:55:16 AM More Than Conquerors Rend Collective The Art Of Celebration (2014) Praise & Worship from Moody Radio 04/28/15 Tuesday 1 A (CT) Air Time (CT) Title Artist Album 1:00:08 AM You Are My All In All Nichole Nordeman WOW Worship: Yellow (2003) 1:03:59 AM How Can It Be Lauren Daigle How Can It Be (2014) 1:08:12 AM Truth Calvin Nowell Start Somewhere 1:11:57 AM The One Aaron Shust Morning Rises (2013) 1:15:52 AM Great Is Thy Faithfulness Avalon Faith: A Hymns Collection (2006) 1:21:50 AM Beyond Me Toby Mac TBA (2015) 1:25:02 AM Jesus, You Are Beautiful Cece Winans Throne Room 1:29:53 AM No Turning Back Brandon Heath TBA (2015) 1:32:59 AM My God Point of Grace Steady On 1:37:28 AM Let Them See You JJ Weeks Band All Over The World (2009) 1:40:46 AM Yours Steven Curtis Chapman This Moment 1:45:28 AM Burn Bright Natalie Grant Hurricane (2013) 1:51:42 AM Indescribable Chris Tomlin Arriving (2004) 1:55:27 AM Made New Lincoln Brewster Oxygen (2014) Praise & Worship from Moody Radio 04/28/15 Tuesday 2 A (CT) Air Time (CT) Title Artist Album 2:00:09 AM Beautiful MercyMe The Generous Mr. -

Set in Scotland a Film Fan's Odyssey

Set in Scotland A Film Fan’s Odyssey visitscotland.com Cover Image: Daniel Craig as James Bond 007 in Skyfall, filmed in Glen Coe. Picture: United Archives/TopFoto This page: Eilean Donan Castle Contents 01 * >> Foreword 02-03 A Aberdeen & Aberdeenshire 04-07 B Argyll & The Isles 08-11 C Ayrshire & Arran 12-15 D Dumfries & Galloway 16-19 E Dundee & Angus 20-23 F Edinburgh & The Lothians 24-27 G Glasgow & The Clyde Valley 28-31 H The Highlands & Skye 32-35 I The Kingdom of Fife 36-39 J Orkney 40-43 K The Outer Hebrides 44-47 L Perthshire 48-51 M Scottish Borders 52-55 N Shetland 56-59 O Stirling, Loch Lomond, The Trossachs & Forth Valley 60-63 Hooray for Bollywood 64-65 Licensed to Thrill 66-67 Locations Guide 68-69 Set in Scotland Christopher Lambert in Highlander. Picture: Studiocanal 03 Foreword 03 >> In a 2015 online poll by USA Today, Scotland was voted the world’s Best Cinematic Destination. And it’s easy to see why. Films from all around the world have been shot in Scotland. Its rich array of film locations include ancient mountain ranges, mysterious stone circles, lush green glens, deep lochs, castles, stately homes, and vibrant cities complete with festivals, bustling streets and colourful night life. Little wonder the country has attracted filmmakers and cinemagoers since the movies began. This guide provides an introduction to just some of the many Scottish locations seen on the silver screen. The Inaccessible Pinnacle. Numerous Holy Grail to Stardust, The Dark Knight Scottish stars have twinkled in Hollywood’s Rises, Prometheus, Cloud Atlas, World firmament, from Sean Connery to War Z and Brave, various hidden gems Tilda Swinton and Ewan McGregor. -

Control of Invasive Non-Native Species in Priority Mesotrophic Lochs R80014PUR

Scottish Environment Protection Agency Control of invasive non-native species in priority mesotrophic lochs R80014PUR Final Report March 2009 Revision Schedule Control of Invasive Non-Native Macrophytes in Mesotrophic Lochs Elodea canadensis and Elodea nuttallii March 2009 Rev Date Details Prepared by Reviewed by Approved by 01 14/08/08 Draft Report Carolyn Cowan Sue Bell Graduate Ecologist Associate Environmental Specialist 02 16/12/08 Draft Report Stephen Clark Sue Bell Assistant Ecologist Associate Environmental Specialist 03 11/03/2009 Final Stephen Clark Sue Bell Sue Bell Assistant Ecologist Associate Environmental Associate Environmental Specialist Specialist Scott Wilson 23 Chester Street EDINBURGH EH3 7EN Tel 0131-225-1230 Fax 0131-225-5582 www.scottwilson.com This document has been prepared in accordance with the scope of Scott Wilson's Table of Contents 1 Introduction ....................................................................................... 4 1.2 Aims...........................................................................................................................................4 1.3 Lochs reviewed.........................................................................................................................4 1.4 Structure of the document .......................................................................................................5 2 Methodology ...................................................................................... 6 2.2 Desk Based Research .............................................................................................................6 -

Beavers in Scotland a Report to the Scottish Government Beavers in Scotland: a Report to the Scottish Government

Beavers in Scotland A Report to the Scottish Government Beavers in Scotland: A report to the Scottish Government Edited by: Martin Gaywood SNH authors (in report section order): Martin Gaywood, Andrew Stringer, Duncan Blake, Jeanette Hall, Mary Hennessy, Angus Tree, David Genney, Iain Macdonald, Athayde Tonhasca, Colin Bean, John McKinnell, Simon Cohen, Robert Raynor, Paul Watkinson, David Bale, Karen Taylor, James Scott, Sally Blyth Scottish Natural Heritage, Inverness. June 2015 ISBN 978-1-78391-363-3 Please see the acknowledgements section for details of other contributors. For more information go to www.snh.gov.uk/beavers-in-scotland or contact [email protected] Beavers in Scotland A Report to the Scottish Government Foreword Beavers in Scotland I am delighted to present this report to Scottish Ministers. It is the culmination of many years of dedicated research, investigation and discussion. The report draws on 20 years of work on beavers in Scotland, as well as experience from elsewhere in Europe and North America. It provides a comprehensive summary of existing knowledge and offers four future scenarios for beavers in Scotland for Ministers to consider. It covers a wide range of topics from beaver ecology and genetics, to beaver interactions with farming, forestry, and fisheries. The reintroduction of a species, absent for many centuries, is a very significant decision for any Government to take. To support the decision- making process we have produced this comprehensive report providing one of the most thorough assessments ever done for a species reintroduction proposal. Ian Ross Chair Scottish Natural Heritage June 2015 Commission from Scottish Ministers to SNH, January 2014 Advice on the future of beavers in Scotland SNH should deliver a report to Scottish Ministers by the end of May 2015 summarising our current knowledge about beavers and setting out a series of scenarios for the future of beavers in Scotland. -

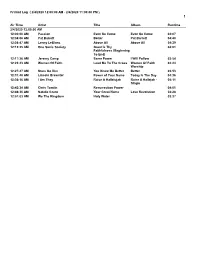

Printed Log ( 2/4/2020 12:00:00 AM - 2/4/2020 11:00:00 PM ) 1

Printed Log ( 2/4/2020 12:00:00 AM - 2/4/2020 11:00:00 PM ) 1 Air Time Artist Title Album Runtime 2/4/2020 12:00:00 AM 12:00:00 AMPassion Even So Come Even So Come 04:07 12:04:06 AM Pat Barrett Better Pat Barrett 04:40 12:08:47 AMLenny LeBlanc Above All Above All 04:39 12:13:25 AM One Sonic Society Great Is Thy 04:01 Faithfulness (Beginning To End) 12:17:26 AM Jeremy Camp Same Power I Will Follow 03:54 12:23:23 AMWomen Of Faith Lead Me To The Cross Women Of Faith 04:24 Worship 12:27:47 AM Stars Go Dim You Know Me Better Better 03:53 12:31:40 AMLincoln Brewster Power of Your Name Today Is The Day 04:36 12:36:16 AMI Am They Raise A Hallelujah Raise A Hallejah - 04:11 Single 12:42:34 AM Chris Tomlin Resurrection Power 04:01 12:46:35 AM Natalie Grant Your Great Name Love Revolution 04:28 12:51:03 AM We The Kingdom Holy Water 03:37 Printed Log ( 2/4/2020 12:00:00 AM - 2/4/2020 11:00:00 PM ) 2 Air Time Artist Title Album Runtime 2/4/2020 1:00:00 AM 1:00:00 AM The Museum My Help Comes From Let Love Win 03:28 The Lord 1:03:27 AMCody Carnes Nothing Else Nothing Else - Single 05:24 1:08:52 AMSteve Green Majesty (Here I Am) Always 05:35 1:14:27 AMTenth Avenue North I Have This Hope Followers 03:19 1:17:47 AMWe Are Messengers Magnify We Are Messengers 03:09 1:23:00 AMTodd Agnew Gloria Need 02:43 1:25:43 AM Leeland Waymaker 05:05 1:30:48 AMNicol Sponberg No Not One Awake My Soul 02:59 1:33:47 AMMack Brock I Am Loved Covered 05:31 1:39:18 AMTodd Agnew Gloria Need 02:43 1:44:07 AMHillsong United Not Today Wonder 03:43 1:47:49 AM Blended Worship Holy -

1/13/2021 12:00:00 AM 05:14 Darlene Zschech 12

Printed Log ( 1/13/2021 Wednesday at 12:00 AM - 1/13/2021 Wednesday at 11:59 PM ) 1 Air Time Artist Title Album Runtime 1/13/2021 12:00:00 AM 12:00:00 AM Darlene Zschech God So Loved You Are My World 05:14 12:05:15 AM Pat Barrett Better Pat Barrett 04:47 12:10:02 AM Passion The Lord Our God Passion: Let The Future 03:49 Begin 12:13:52 AM Matt Redman Let Everything That Intimacy 02:43 Has Breath 12:16:34 AM Kari Jobe The Blessing The Blessing 04:17 12:23:35 AM Vertical Worship Yes I Will Bright Faith Bold 03:32 Future 12:27:07 AM Todd Agnew Gloria Need 02:43 12:29:52 AM Red Rocks Worship Breakthrough Breakthrough (Single 03:56 Version) 12:33:48 AM Michael W. Smith The Stand Stand 02:49 12:36:38 AM Mack Brock I Am Loved Covered 05:31 12:44:46 AM Natalie Grant King of the World Be One 03:21 12:48:07 AM Michael W. Smith Waymaker Way Maker 03:55 12:52:01 AM Chris Renzema Springtime Springtime 04:06 Printed Log ( 1/13/2021 Wednesday at 12:00 AM - 1/13/2021 Wednesday at 11:59 PM ) 2 Air Time Artist Title Album Runtime 1/13/2021 1:00:00 AM 1:00:00 AM Darlene Zschech At The Cross At The Foot of the 04:14 Cross 1:04:21 AM Chris Tomlin Resurrection Power Holy Roar 04:01 1:08:22 AM SEU Worship Fire in My Bones Brand New Worship 03:20 1:11:42 AM Selah Hosanna You Deliver Me 04:03 1:15:45 AM Jonathan Traylor You Get The Glory The Unknown 03:47 1:22:19 AM Shannon Wexelberg Count It All Joy Better Than Life 04:12 1:26:32 AM Elevation Worship Graves Into Gardens Graves into Gardens 04:10 1:30:41 AM Pat Barrett Build My Life Build My Life - EP 04:16 1:34:57 -

2010Pvcatalogindexpages837-880.Pdf

index 838 INDEX A-Z of Classical Music .............................................. 405 Acoustic Rock Guitar Songs for Dummies ................ 490 All American Boogie Woogie .................................... 437 Aaberg, Philip – Piano Solos ...................................... 77 Acoustic Rock Hits – Easy Guitar.............................. 490 All American Folk .................................................... 426 AB Real Book ............................................................. 46 Across the Universe – All American Rejects – Move Along ............................ 80 Abair, Mindi – Collection – Music from the Motion Picture – P/V/G ............ 275 All Around the U.S.A. – P/V/G ........................... 484, 562 Saxophone Artist Transcriptions .......................... 77 Across the Universe – Music from the Motion Picture – All Creatures of Our God and King ........................... 784 ABBA – Best of ........................................................... 77 Original Keys for Singers ................................... 611 All Music Guide to Classical Music ........................... 414 ABBA – Gold: Greatest Hits ......................................... 77 Actor’s Songbook .....................................268, 562, 581 All Shook Up – Vocal Selections ............................... 264 ABBA – Pro Vocal Women’s Edition ................. 360, 614 Adams, Bryan – Anthology ......................................... 78 All That Remains – Fall of Ideals ................................ 80 Above All – Phillip -

Unit 6 Using Maps

Bright star -English for grade 7 –second term 2018-Mr:Mohammed lotfy 0503437147 UNIT 6 USING MAPS عربة كارو carriage منذ زمن For ages كاتالوج catalogue وسط المدينة City center يغير الى change to يغير change يغير من اجل change for اختصار abbreviation بوصلة compass يصل الى arrive at بالتاكيد definitely رائد فضاء astronaut قارب صغير astronomy dhow اتجاة direction خلف behind يقود عائدا drive back مكان ركن السيارة car park Read the conversations and answer the questions: ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- Ahmed: Hey, Saif. I haven’t seen you for ages. Saif: Ahmed. Good to hear from you. Ahmed: Where are you? At home? Saif: Now? No, I’m in the city centre. Ahmed: What are you doing? Saif: I’m in the bank. You know we’re going to England next week? So, I’ve come here to change some money. Conversation 2 Yousif: Mohammed? It’s me. Where are you? Mohammed: Hi Yousif. I’m at the police academy. Yousif: Really? I thought you were going to the cinema. Mohammed: Yes, I am later. You know my cousin Safwan? I came here to visit him. He’s training to be a police officer. We’re going to the cinema this evening. Bright star -English for grade 7 –second term 2018-Mr:Mohammed lotfy 0503437147 Conversation 3 Murad: Hi Khaled. Khaled: Hi, Murad. How are you? Murad: Fine thanks. It’s loud there - are you in a metro station? Khaled: No, I’m in the mall. Murad: What are you doing? Shopping again? Khaled: Yes. I need a new watch, so I came here to buy one. -

CEFC Update for 11.17.17

C O M M U N I T Y E V A N G E L I C A L F R E E C H U R C H W E E K L Y N E W S L E T T E R N O V E M B E R 1 7 , 2 0 1 7 CEVOANGMELICMAL FUREEN CHIUTRCYH P U R S U I N G G O D \ \ L O V I N G P E O P L E \ \ D E V E L O P I N G D I S C I P L E M A K E R S THIS WEEK'S NEWS - A community Thanksgiving service will be held at Westview Methodist Church this Sunday Community at 6:30 pm. All are encouraged to attend. There will be fellowship following the service, so please bring a pie to share. Those who attend are also encouraged to bring a Thanksgiving Service canned good item to donate to the local Food Pantry. Westview Methodist Sunday, 6:30pm - 180° youth group will not be meeting next Wednesday, November 22 due to Thanksgiving. It will resume for a game night (board games, large group games, etc.) on the following Wednesday, November 29th! All 7th-12th graders are welcome to join us! Bring friends and a few snacks to share! - The church office will be closed on November 23-24 for Thanksgiving. Regular office hours will resume the following Tuesday, November 28th. Membership Class Dec. 10 - A new small group bible study is starting on Tuesday, November 28th at 7:00 pm at Les & 12pm-2pm Georgia John's home.