Encounters with Winston Churchill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sevenoaks District Accommodation Availability List

Sevenoaks District Accommodation Availability List Eastern Sevenoaks: Chipstead, Crouch, Dunk’s Green, Ightham, Kemsing, Seal, Shipbourne, Stone Street, Wrotham Heath Western Sevenoaks: Brasted, Cowden, Edenbridge, Marsh Green Locations: Northern Sevenoaks: Dunton Green, Knockholt, Shoreham Southern Sevenoaks: Hildenborough, Tonbridge, Weald Central Sevenoaks: Sevenoaks town EASTERN SEVENOAKS : Chipstead, Crouch, Dunk’s Green, Ightham, Kemsing, Seal, Shipbourne, Stone Street, Wrotham Heath Current Availability 13 – 27 November 2017 Chipstead/ Crossways House Ensuite room or private Chevening Cross Rd Chevening £: 50 – 90; apartment £85 per night Please phone for latest bathroom near Chevening/Chipstead TN14 6HF availability 2 bed/2 bath self-catering Mrs Lela Weavers apartment for 6 Near Darent Valley Path & North T: 01732 456334 Downs Way. E: [email protected] Borough Green, Yew Tree Barn WiFi access Long Mill Lane (Crouch) £: 60 – 130 13 – 27 November Ensuite rooms Crouch Family rooms Borough Green TN15 8QB Tricia & James Barton Guest sitting rooms T: 01732 780461 or 07811 505798 Partial disabled room(s) Converted barn built around 1810 E: [email protected] located in a tranquil, secluded hamlet www.yewtreebarn.com with splendid views across open countryside. Excellent base for touring Kent, Sussex & London. Ightham The Studio at Double Dance Broadband Tonbridge Road £: 70 – 80 15 - 23 November WiFi access Ightham TN15 9AT Ensuite room A stylish self-contained annexe Penny Cracknell Kent Breakfast overlooking -

THE CHURCHILLIAN Churchill Society of Tennessee 2Nd Summer Edition 2020

THE CHURCHILLIAN Churchill Society of Tennessee 2nd Summer Edition 2020 Sir Winston Churchill’s Statue Parliament Square London This 12-foot-tall bronze statue of Churchill in Parliament Square was designed by Ivor Roberts- Jones. The statue was dedicated in 1972 by Churchill’s wife Lady Churchill at a ceremony attended by HRH Queen Elizabeth II and four Prime Ministers. The location of the statue was chosen by Churchill himself and was inspired by that now-famous photo of him inspecting the bomb-damaged Chamber of the Commons in Westminster on May 11, 1941. The Churchillian Page 1 Inside this issue of the Churchillian Page 4. Farewell to the Earl Page 5. Coronavirus, the Queen and the 75th anniversary of VE Day. Dame Vera Lynn’s last article from the May 2020 issue of the Oldie Magazine Page 8. Lady Churchill’s Rose Garden, a special visit by Beryl Nicholson Page 10. A Tour of the Gardens at Chartwell House, beloved home of Sir Winston Churchill by Jim Drury Page 29. Why are the Churchill Statue and all our other monuments so important? A quote from Andrew Roberts Page 30. Resource Page The Churchillian Page 2 THE CHURCHILL SOCIETY OF TENNESSEE Patron: Randolph Churchill Board of Directors: Executive Committee: President: Jim Drury Vice President Secretary: Robin Sinclair PhD Vice President Treasurer: Richard Knight Esq Comptroller: The Earl of Eglinton & Winton, Hugh Montgomery - Robert Beck Don Cusic Beth Fisher Michael Shane Neal - Administrative officer: Lynne Siesser - Past President: Dr John Mather - Sister Chapter: Chartwell Branch, Westerham, Kent, England - Contact information: Churchillian Editor: Jim Drury www.churchillsocietytn.org Churchill Society of Tennessee PO BOX 150993 Nashville, TN 37215 USA 615-218-8340 The Churchillian Page 3 Farewell to the Earl! It is with regret that we must announce the departure of The Earl of Eglinton & Winton, the Rt. -

Sir Winston Churchill's Feline Legacy – Jock of Chartwell House

CAT TOURISM By SANdy RoBINS ETT N E BAR N RY JARVIS RY N of cats AL TRUST/HE AL AL TRUST/KATHERI AL N N ATIO ATIO N N love AL TRUST/ROBERT MORRIS AL N OURTESY OURTESY OURTESY OURTESY C C ATIO N Jock VI, the current feline as they were when Sir Winston was ARTER OURTESY OURTESY C resident, lives in the top-floor in residence, with pictures, books, C N for the flat at Chartwell with Katherine and personal mementos evoking the Barnett, the house and collections career and wide-ranging interests AL TRUST/IAI AL manager. He took office in March of a great statesman, writer, painter, N 2014, when his predecessor, Jock and family man. Embrace V, retired from public life and “Also, Churchill was very fond SIEDEL went to live with a former house of all animals, and, along with his COURTESY NATIO COURTESY N I E Winston N and collections manager in the request for a marmalade cat to be Scottish countryside. in residence, we also have many by the gift shop, where there are Churchill’s DREAS VO “It’s a modern day rags-to- other animals that are a part of his shortbread biscuits, fudge, and, of AN riches story,” Barnett said of the animal-loving legacy, including two course, marmalade with Jock’s face RUST/ Cat Love at T current Jock, who was adopted black swans on our lake and his on the packaging. AL N from a local animal rescue. “Jock golden orfe in the pond.” You can also find a range of the Chartwell VI has had a difficult start to his This year has been a very busy jewelry, including a necklace, Estate life. -

Curt J. Zoller Churchill Collection: Printed Materials and Ephemera: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8q52v6j No online items Curt J. Zoller Churchill Collection: Printed Materials and Ephemera: Finding Aid Finding aid prepared by K. Peck. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Rare Books Department The Huntington Library 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2015 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Curt J. Zoller Churchill Collection: 609303 1 Printed Materials and Ephemera: Finding Ai... Overview of the Collection Title: Curt J. Zoller Churchill Collection: Printed Materials and Ephemera Dates (inclusive): 1902-2010 Bulk dates: 1930-1966 Collection Number: 609303 Compiler: Zoller, Curt J., 1920-2014 Extent: approximately 550 items in 17 boxes, 2 oversized folders, and 1 bound volume. Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Rare Books Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: The Curt J. Zoller Churchill Collection: Printed Materials and Ephemera contains approximately 550 items related to British statesman Winston Churchill (1874-1965). The items date from 1902 to 2010 and consist of articles from a variety of periodicals by and about Churchill, the text of speeches delivered by Churchill, ephemera, audio and visual materials, and printed World War II propaganda in a variety of languages. Language: Danish, Dutch, English, French, German, Greek, Italian, Luxembourgish, and Norwegian. Note: Finding aid last updated on August 28, 2015. Access The collection is open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. -

7 Ringside , Edenbridge, Kent, TN8 6GD

7 Ringside , Edenbridge, Kent, TN8 6GD 7 Ringside , Edenbridge, Kent, TN8 6GD A spacious four bedroom detached family home located on a popular residential development in Edenbridge. This property benefits from a generous southerly facing garden and ample off road parking with a double garage in tandem. Double tandem garage Quiet residential area Ample off road parking En-suite shower rooms Family bathroom Close to two railway stations Close to local amenities Close to town centre Well presented throughout Secluded southerly facing garden £500,000 DESCRIPTION A spacious four bedroom detached family home located on a popular residential development in Edenbridge. This property benefits from a generous southerly facing garden and ample off road parking with a double garage in tandem. Entering the house, a large entrance hall leads through to the living accommodation. The living room overlooks the rear garden with double glazed patio doors leading out; this room offers a generous space for relaxing and unwinding. Just off the living room you have a useful separate dining room with space for a table that can seat 6-8 guests. Going back to the rear of the property the kitchen also overlooks the garden with door leading out. This kitchen offers a range of wall and base units with worktops over along with plenty of space for a kitchen table for everyday family use. It also comes with a range of fitted appliances including double oven, dishwasher, fridge/freezer and washer/dryer, all of which are included in the sale. Rounding off the ground floor accommodation is a study situated at the front of the house; this room can also be used as a snug or playroom. -

The Life of Winston Churchill

© Yousuf Karsh, 1941 Ottawa The Life of Winston Churchill: Soldier Correspondent Statesman Orator Author Inspirational Leader © The Churchill Centre 2007 Produced for educational use only. Not intended for commercial purposes. The Churchill Centre is the international focus for study of Winston Churchill, his life and times. Our members, aged from ten to over ninety, work together to preserve Winston Churchill's memory and legacy. Our aim is that future generations never forget his contribu- tions to the political philosophy, culture and literature of the Great Democracies and his contributions to statesmanship. To join or contact The Churchill Centre visit www.winstonchurchill.org Birth 1874 Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill’s ancestors were both Brit- ish and American. Winston’s father was the British Lord Randolph Churchill, the youngest son of John, the 7th Duke of Marlborough. Lord Randolph’s ancestor John Churchill made history by winning many successful military campaigns in Europe for Queen Anne almost 200 years earlier. His mother was the American Jennie Jerome. The Jeromes fought for the inde- pendence of the American colonies in George Washington’s ar- mies. Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill was born on Novem- ber 30, 1874, at the Duke of Marlborough’s large palace, Blen- Winston. as a baby. heim. Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill’s family tree John Churchill 1650-1722 1st Duke of Marlborough !" Charles 1706-1758 3rd Duke of Marlborough !" George 1739-1817 David Wilcox 4th Duke of Marlborough !" John Churchill George 1766-1840 -

The Old Sawmill, Hill Hoath Road, Chiddingstone, TN8 7AB

The Old Sawmill, Hill Hoath Road, Chiddingstone, TN8 7AB £950,000 The Old Sawmill, Hill Hoath Road, Chiddingstone, TN8 7AB A stunning four bedroom detached barn set within the glorious surrounds of Chiddingstone. Beautifully presented throughout and offered with ample off road parking and car port area. Quiet rural location Short drive to Edenbridge Car port railway station Open plan living space Three double bedrooms En-suite to master bedroom Stunning surrounds in two acre plot Close to Chiddingstone castle Wood burner Short drive to local amenities DESCRIPTION A stunning four bedroom detached barn set within the glorious surrounds of Chiddingstone. Beautifully presented throughout and offered with ample off road parking and car port area. Entering the house, a large entrance hall leads through to the living accommodation. The kitchen, dining room and breakfast room enjoy an open plan feel with views over the rear garden. The well thought out design by the current owners make this space flexible and inviting with doors off of the breakfast area opening onto the rear decking overlooking the beautiful gardens. There are four double bedrooms, of which the master enjoys a shower en-suite. There is also a separate family bathroom with shower over bath. The whole property benefits from zoned under floor heating, giving the house a minimalistic look without any radiators on the walls. Externally The Old Sawmill benefits from a large car port just off the generous sweeping driveway with parking for several cars. To the rear of the house you are surrounded by rural views and woodland. The whole plot extends to around two acres, giving you complete space and freedom to do as you will outside. -

Chartfield Cottage Chart Lane, Brasted Chart, Westerham, Kent, TN16 1LX

Chartfield Cottage Chart Lane, Brasted Chart, Westerham, Kent, TN16 1LX A charming semi-detached There are golf courses at Westerham and Limpsfield Chart as well as Knole and Wildernesse in cottage with delightful Sevenoaks, Nizels Golf and Leisure Centre in Hildenborough. Health Centre and pool complex in gardens and some Oxted. National Trust properties include Chartwell wonderful views and Emmetts. There are also numerous footpaths in the local vicinity. conveniently situated in this popular location Description Chartfield Cottage is an attractive semi-detached cottage believed to have been built in the early Guide Price £590,000 1900's by Durtnells, with brick and tile hung elevations under a tiled roof. The house and its Location other half are also understood to have been built as o Brasted about 1.5 miles Housekeeper/Gardeners accommodation for Lord o Sevenoaks Station about 5 miles Stanhope who’s daughter lived in the house to the o Oxted about 7 miles. rear. The present owners have further improved the Situation property with the construction of the conservatory Chartfield Cottage is set within an Area of on the rear elevation and replacing all windows. Outstanding Natural Beauty on the edge of the Outside the gardens are a particular feature and historic village of Brasted with its good day to provide a most attractive setting. There are some day facilities. Westerham also offers a good range wonderful views particularly from first and second of local shopping facilities as well as many floor windows. restaurants. Sevenoaks and Oxted town centres both offer a Features wide range of shopping and leisure facilities. -

Westerham/Chartwell

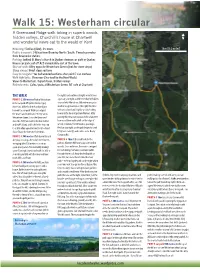

Walk 15: Westerham circular A Greensand Ridge walk taking in superb woods, ▲ hidden valleys, Churchill’s house at Chartwell N and wonderful views out to the weald of Kent How long? 5 miles (8km), 2½ hours 1km (0.6 miles) Public transport: 246 bus from Bromley North/South. Three bus routes from Sevenoaks station. Parking: behind St Mary’s church in Quebec Avenue car park or Quebec House car park just off A25 immediately east of the town. Start of walk: Alley opposite Westerham Green (look for stone steps) Steep slopes? Brief steep sections Easy to navigate? Yes but wooded sections after point 7 can confuse Walk highlights: View over Chartwell to the Kent Weald. Views to Westerham. Superb trees, hidden valleys Refreshments: Cafes/pubs at Westerham Green. NT cafe at Chartwell THE WALK the right) and continue straight on with trees POINT 1-2 350 metres Park in Westerham again on your right and the river Darent hidden in the car park off Quebec Avenue (pay on your left. After about 300 metres you pass Mon-Sat). Make for the churchyard just another long meadow on the right, this time beyond the car park. Walk up and past with an isolated and slightly spooky looking the graves and church and emerge on to house at the far end (pictured below). After Westerham Green. Cross the Green and passing this meadow you pass behind another cross the A25 from next to the bus shelter house and then walk uphill on the edge of and traffic island and look for the steps up woods. -

Churchill Goes on Tour Written by Billy Mayer Many Fellow Churchillians

Churchill Goes on Tour Written by Billy Mayer Many fellow Churchillians, avid historians, and adventurers have experienced the important landmarks that encapsulated Winston Churchill’s historical preeminence; however, few have visited all of the major sites in a compressed time period. As part of my fellowship awarded through the National Churchill Library Center and the ICS, I embarked on a massively packed two-week trip to visit the historic Churchill sites and conduct research for my master’s thesis on Churchill’s historical inspirations. After conversing with Tim Riley, Director of the National Churchill Museum of America in Fulton, Missouri, I decided to create a travelogue to share and reflect upon my experiences at these Churchillian hotspots. During my trip I visited the Churchill War Rooms in London, travelled to Chartwell-Churchill’s estate, drank champagne with Andrew Roberts, collaborated intensively with Director Allen Packwood at the Churchill Archives Centre in Cambridge, and concluded my adventure with a visit to the National Churchill Museum of America in Fulton, Missouri. Only a week after stuffing my face with turkey on Thanksgiving and finishing up my third term at Hawaii Pacific University, I embarked on my Churchillian pilgrimage traveling thousands of miles from a small island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean to London, England. I must say I was not prepared for the dreadfully cold weather of the United Kingdom. Flying over in board shorts, a coconut bra, and hula skirt was most likely one of the poorest decisions I have made since the 1915 Dardanelles Campaign. But surprisingly unlike the many brave souls that stormed Gallipoli, I arrived and survived the brutality of the British weather systems. -

Randy Otto's Winston Churchill: ”The Blitz”

Randy Otto’s Winston ChurChill: ”the blitz” The British People had The Lion’s Heart, Winston Churchill had the luck to give The Roar! Blitz Sizzle Reel https://vimeo.com/236987470/0d8d38de23 Office: 920-988-4459 http://churchillspeaker.com about randy otto as Winston ChurChill With over 4 decades of formidable academic and performance passion, audiences experience an astonishingly nuanced, humorous, witty, REAL Winston Churchill with gravitas and grit as randy otto shatters the imaginary 4th wall, transporting your audience from tears to laughter and back again. Jonathan Sandys Great-Grandson of Sir Winston Churchill “I have heard many people attempt to play the role of my great-grandfather, but without hesitation, Randy Otto takes the role to a whole new level. Randy does not attempt to be Winston Churchill, Randy Otto IS Winston Churchill.” Tim Riley – Executive Director National Churchill Museum – Fulton, MO “Randy Otto is to Winston Churchill as Hal Holbrook is to Mark Twain.” Hal Holbrook “I'm glad you are pursuing your show on the road and enjoying it. That is all to the good for you and your audiences. We have a mission Randy. We may not play the enormous crowds, like the rock 'n' roll type shows do, but we have our place in the history of The Road.” synopsis Winston ChurChill: the blitz randy otto portrays Churchill’s unwavering, audacious belief that if the British People were simply trusted with the truth – no matter how bad things got – they would only get stronger and more resilient. aCt i From his study at Chartwell, Winston Churchill recounts his courageous 1930’s journey from historical footnote to the most beloved leader and statesman in recorded history. -

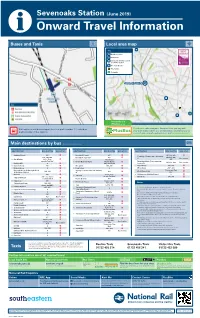

Sevenoaks Station (June 2019) I Onward Travel Information Buses and Taxis Local Area Map

Sevenoaks Station (June 2019) i Onward Travel Information Buses and Taxis Local area map BL Key BL Bradborne Lakes KP Knole Park SC Sevenoaks District Council and Police Station ST The Stag Theatre Bus Station Footpaths Sevenoaks Station SC KP ST Sevenoaks is a PlusBus area Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2018 & also map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, CC BY-SA Rail replacement buses depart from car park number 1 (Tonbridge PlusBus is a discount price ‘bus pass’ that you buy with your train ticket. It gives you unlimited bus travel around your platform side of the station). chosen town, on participating buses. Visit www.plusbus.info Main destinations by bus (Data correct at June 2019) DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP Badgers Mount 431 A Knockholt Pound 431 A 401(Su), 435 B Tonbridge (Town Centre & Station) 6, 8, 306, 308, ^ 431 A 401(Su), 402, Knockholt Station ^ Bus Station { Bat & Ball ^ 421+, 'Sev- A 'Free Knole 435 enoaks Taxi Bus' Tunbridge Wells (Town Centre & { Knole (National Trust) Shuttle Bus''#, B 401(Su), 402 Bus Station Bayleys Hill 4 B 8##, 401(Su)## Station) ^ { Bessel's Green 401 A Meopham 306, 308 A Vigo Village 306, 308 A Bitchet Green 4 A { Noah's Ark 6 A Westerham 238*, 401 A Borough Green (& Borough Green Orpington (Town Centre & Station) 'Sevenoaks Taxi 306, 308 A 431 A West Kingsdown A & Wrotham Station) ^ Bus' Brasted 401 A 421+, 'Sev- { Wildernesse (Blackhall Lane) 8 A { Otford ^ A 238* or a Taxi is enoaks Taxi Bus' Wrotham 306, 308 A Chartwell House A recommended Pratt's Bottom 431 A { Chipstead 401 A 6(Sat), 8, 401, { Riverhead (Tesco) A Culverstone Green 306, 308 A 431, 435 Notes 6(Sat), 401(MF), { Seal 6, 306, 308 A { Dunton Green ^ A 431, 435 Sevenoaks (Bayham Road/ { PlusBus destination, please see below for details.