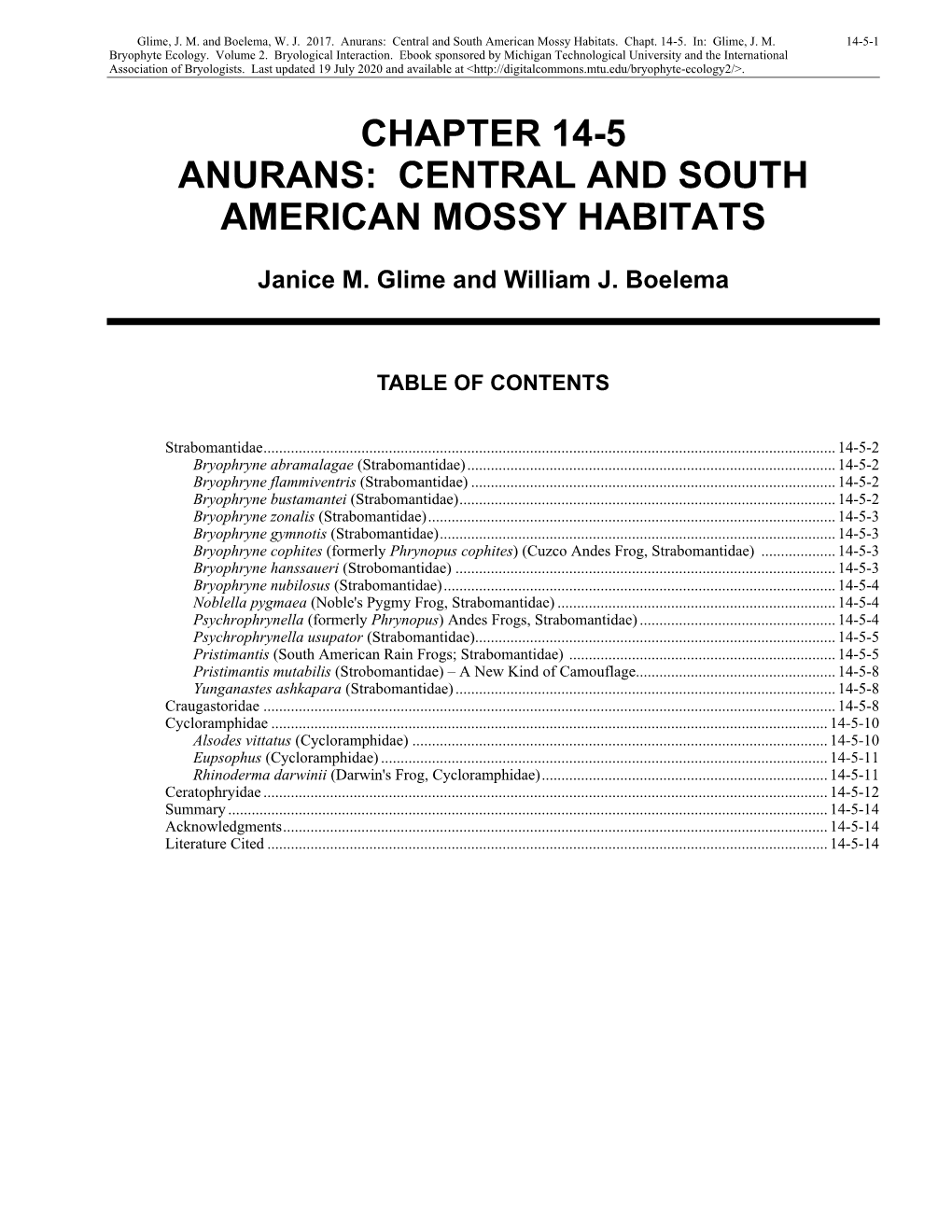

Volume 2, Chapter 14-5: Anurans: Central and South American Mossy Habitats

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Collection of Amphibians from Río San Juan, Southeastern Nicaragua

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264789493 A collection of amphibians from Río San Juan, southeastern Nicaragua Article in Herpetology Notes · January 2009 CITATIONS READS 12 188 4 authors, including: Javier Sunyer Matthias Dehling University of Canterbury 89 PUBLICATIONS 209 CITATIONS 54 PUBLICATIONS 967 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Gunther Köhler Senckenberg Research Institute 222 PUBLICATIONS 1,617 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Zoological Research in Strict Forest Reserves in Hesse, Germany View project Diploma Thesis View project All content following this page was uploaded by Javier Sunyer on 16 August 2018. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Herpetology Notes, volume 2: 189-202 (2009) (published online on 29 October 2009) A collection of amphibians from Río San Juan, southeastern Nicaragua Javier Sunyer1,2,3*, Guillermo Páiz4, David Matthias Dehling1, Gunther Köhler1 Abstract. We report upon the amphibians collected during seven expeditions carried out between the years 2000–2006 to thirteen localities in both Refugio de Vida Silvestre Río San Juan and Reserva Biológica Indio-Maíz, southeastern Nicaragua. We include morphometric data of around one-half of the adult specimens in the collection, and provide a brief general overview and discuss zoogeographic and conservation considerations of the amphibians known to occur in the Río San Juan area. Keywords. Amphibia, conservation, ecology, morphometry, zoogeography. Introduction potential of holding America’s first interoceanic channel and also because it was part of the sea route to travel The San Juan River is an approximately 200 km slow- from eastern to western United States. -

Chec List a Checklist of the Amphibians and Reptiles of San

Check List 10(4): 870–877, 2014 © 2014 Check List and Authors Chec List ISSN 1809-127X (available at www.checklist.org.br) Journal of species lists and distribution PECIES S OF A checklist * of the amphibians and reptiles of San Isidro de ISTS L Dota, Reserva Forestal Los Santos, Costa Rica Erick Arias and Federico Bolaños [email protected] Universidad de Costa Rica, Escuela de Biología, Museo de Zoología. San Pedro, 11501-2060, San José, Costa Rica. * Corresponding author. E-mail: Abstract: We present an inventory of amphibians and reptiles of San Isidro de Dota, northwest of the Cordillera de Talamanca in the Central Pacific of Costa Rica.Leptodactylus The study was insularum conduced from January to August 2012 in premontane wet Coloptychonforest from 689 rhombifer m to 800 m elevation. We found a total of 56 species, including 30 species of amphibians and 26 of reptiles. It results striking the presence of the frog , uncommon above 400 m elevation, and the lizard , a very uncommon species. DOI: 10.15560/10.4.870 Introduction datum, from 689 m to 800 N, 83°58′32.41″ W, WGS84et al. Lower Central America represents one of the regions m elevation). The region is dominated by premontane with the highest numberet al of amphibianset describedal. in the wet forest (Bolaños 1999) with several sites used Neotropics in relation to the area it represent (Savage for agriculture and pastures. The region presents the 2002; Boza-Oviedo . 2012; Hertz 2012). Much climate of the pacific slope of the Cordillera de Talamanca, of this richness of species iset associated al. -

Aspects of the Ecology and Conservation of Frogs in Urban Habitats of South Africa

Frogs about town: Aspects of the ecology and conservation of frogs in urban habitats of South Africa DJD Kruger 20428405 Thesis submitted for the degree Philosophiae Doctor in Zoology at the Potchefstroom Campus of the North-West University Supervisor: Prof LH du Preez Co-supervisor: Prof C Weldon September 2014 i In loving memory of my grandmother, Kitty Lombaard (1934/07/09 – 2012/05/18), who has made an invaluable difference in all aspects of my life. ii Acknowledgements A project with a time scale and magnitude this large leaves one indebted by numerous people that contributed to the end result of this study. I would like to thank the following people for their invaluable contributions over the past three years, in no particular order: To my supervisor, Prof. Louis du Preez I am indebted, not only for the help, guidance and support he has provided throughout this study, but also for his mentorship and example he set in all aspects of life. I also appreciate the help of my co-supervisor, Prof. Ché Weldon, for the numerous contributions, constructive comments and hours spent on proofreading. I owe thanks to all contributors for proofreading and language editing and thereby correcting my “boerseun” English grammar but also providing me with professional guidance. Prof. Louis du Preez, Prof. Ché Weldon, Dr. Andrew Hamer, Dr. Kirsten Parris, Prof. John Malone and Dr. Jeanne Tarrant are all dearly thanked for invaluable comments on earlier drafts of parts/the entirety of this thesis. For statistical contributions I am especially also grateful to Dr. Andrew Hamer for help with Bayesian analysis and to the North-West Statistical Services consultant, Dr. -

Appendix 1: Maps and Plans Appendix184 Map 1: Conservation Categories for the Nominated Property

Appendix 1: Maps and Plans Appendix184 Map 1: Conservation Categories for the Nominated Property. Los Alerces National Park, Argentina 185 Map 2: Andean-North Patagonian Biosphere Reserve: Context for the Nominated Proprty. Los Alerces National Park, Argentina 186 Map 3: Vegetation of the Valdivian Ecoregion 187 Map 4: Vegetation Communities in Los Alerces National Park 188 Map 5: Strict Nature and Wildlife Reserve 189 Map 6: Usage Zoning, Los Alerces National Park 190 Map 7: Human Settlements and Infrastructure 191 Appendix 2: Species Lists Ap9n192 Appendix 2.1 List of Plant Species Recorded at PNLA 193 Appendix 2.2: List of Animal Species: Mammals 212 Appendix 2.3: List of Animal Species: Birds 214 Appendix 2.4: List of Animal Species: Reptiles 219 Appendix 2.5: List of Animal Species: Amphibians 220 Appendix 2.6: List of Animal Species: Fish 221 Appendix 2.7: List of Animal Species and Threat Status 222 Appendix 3: Law No. 19,292 Append228 Appendix 4: PNLA Management Plan Approval and Contents Appendi242 Appendix 5: Participative Process for Writing the Nomination Form Appendi252 Synthesis 252 Management Plan UpdateWorkshop 253 Annex A: Interview Guide 256 Annex B: Meetings and Interviews Held 257 Annex C: Self-Administered Survey 261 Annex D: ExternalWorkshop Participants 262 Annex E: Promotional Leaflet 264 Annex F: Interview Results Summary 267 Annex G: Survey Results Summary 272 Annex H: Esquel Declaration of Interest 274 Annex I: Trevelin Declaration of Interest 276 Annex J: Chubut Tourism Secretariat Declaration of Interest 278 -

Characterization of an Alsodes Pehuenche Breeding Site in the Andes of Central Chile

Herpetozoa 33: 21–26 (2020) DOI 10.3897/herpetozoa.33.e49268 Characterization of an Alsodes pehuenche breeding site in the Andes of central Chile Alejandro Piñeiro1, Pablo Fibla2, Carlos López3, Nelson Velásquez3, Luis Pastenes1 1 Laboratorio de Genética y Adaptación a Ambientes Extremos, Departamento de Biología y Química, Facultad de Ciencias Básicas, Universidad Católica del Maule. Av. San Miguel #3605, Talca, Chile 2 Laboratorio de Genética y Evolución, Departamento de Ciencias Ecológicas, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Chile. Las Palmeras #3425, Santiago, Chile 3 Laboratorio de Comunicación Animal, Departamento de Biología y Química, Facultad de Ciencias Básicas, Universidad Católica del Maule, Av. San Miguel #3605, Talca, Chile http://zoobank.org/E7A8C1A6-31EF-4D99-9923-FAD60AE1B777 Corresponding author: Luis Pastenes ([email protected]) Academic editor: Günter Gollmann ♦ Received 10 December 2019 ♦ Accepted 21 March 2020 ♦ Published 7 April 2020 Abstract Alsodes pehuenche, an endemic anuran that inhabits the Andes of Argentina and Chile, is considered “Critically Endangered” due to its restricted geographical distribution and multiple potential threats that affect it. This study is about the natural history of A. pe- huenche and the physicochemical characteristics of a breeding site located in the Maule mountain range of central Chile. Moreover, the finding of its clutches in Chilean territory is reported here for the first time. Finally, a description of the number and morphology of these eggs is provided. Key Words Alsodidae, Andean, Anura, endemism, highland wetland, threatened species The Andean border crossing “Paso Internacional Pehu- and long roots arranged in the form of cushions, hence the enche” (38°59'S, 70°23'W, 2553 m a.s.l.) is a bioceanic name “cushion plants” (Badano et al. -

Zootaxa, a New Species of Bryophryne (Anura

Zootaxa 1784: 1–10 (2008) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2008 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) A new species of Bryophryne (Anura: Strabomantidae) from southern Peru EDGAR LEHR1 & ALESSANDRO CATENAZZI2, 3 1Staatliche Naturhistorische Sammlungen Dresden, Museum für Tierkunde, Königsbrücker Landstrasse 159, D-01109 Dresden, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] 2Division of Integrative Biology, University of South Florida, 4202 East Fowler Ave, Tampa, FL 33620, USA 3Present address: Department of Integrative Biology, University of California at Berkeley. 3060 Valley Life Sciences Bldg #3140, Ber- keley CA 94720, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract A new species of Bryophryne from southern Peru (Cusco Region) is described. Specimens were found in the leaf litter of cloud forest at elevations of 2350–3215 m. The new species has a maximum snout-vent length of 21.9 mm in adult females, 18.9 mm in adult males and is the smallest species of the genus. It lacks a tympanum and dentigerous processes of vomers, has dorsolateral folds, and males without vocal slits and without nuptial pads. The new species is most similar to B. bustamantei but differs in being smaller, having discontinuous dorsolateral folds, the males lacking vocal slits, and an overall darker ventral coloration. Bryophryne contains three species all of which lack a tympanum. The deep valley of the Río Apurímac as a distributional barrier separating Phrynopus from Bryophryne is discussed. Key words: Andes, biogeography, Bryophryne cophites, Bryophryne bustamantei Resumen Se describe una nueva especie de Bryophryne del sur de Perú (Región Cusco). -

Polyploidy and Sex Chromosome Evolution in Amphibians

Chapter 18 Polyploidization and Sex Chromosome Evolution in Amphibians Ben J. Evans, R. Alexander Pyron and John J. Wiens Abstract Genome duplication, including polyploid speciation and spontaneous polyploidy in diploid species, occurs more frequently in amphibians than mammals. One possible explanation is that some amphibians, unlike almost all mammals, have young sex chromosomes that carry a similar suite of genes (apart from the genetic trigger for sex determination). These species potentially can experience genome duplication without disrupting dosage stoichiometry between interacting proteins encoded by genes on the sex chromosomes and autosomalPROOF chromosomes. To explore this possibility, we performed a permutation aimed at testing whether amphibian species that experienced polyploid speciation or spontaneous polyploidy have younger sex chromosomes than other amphibians. While the most conservative permutation was not significant, the frog genera Xenopus and Leiopelma provide anecdotal support for a negative correlation between the age of sex chromosomes and a species’ propensity to undergo genome duplication. This study also points to more frequent turnover of sex chromosomes than previously proposed, and suggests a lack of statistical support for male versus female heterogamy in the most recent common ancestors of frogs, salamanders, and amphibians in general. Future advances in genomics undoubtedly will further illuminate the relationship between amphibian sex chromosome degeneration and genome duplication. B. J. Evans (CORRECTED&) Department of Biology, McMaster University, Life Sciences Building Room 328, 1280 Main Street West, Hamilton, ON L8S 4K1, Canada e-mail: [email protected] R. Alexander Pyron Department of Biological Sciences, The George Washington University, 2023 G St. NW, Washington, DC 20052, USA J. -

The Most Frog-Diverse Place in Middle America, with Notes on The

Offcial journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 13(2) [Special Section]: 304–322 (e215). The most frog-diverse place in Middle America, with notes on the conservation status of eight threatened species of amphibians 1,2,*José Andrés Salazar-Zúñiga, 1,2,3Wagner Chaves-Acuña, 2Gerardo Chaves, 1Alejandro Acuña, 1,2Juan Ignacio Abarca-Odio, 1,4Javier Lobon-Rovira, 1,2Edwin Gómez-Méndez, 1,2Ana Cecilia Gutiérrez-Vannucchi, and 2Federico Bolaños 1Veragua Foundation for Rainforest Research, Limón, COSTA RICA 2Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica, San Pedro, 11501-2060 San José, COSTA RICA 3División Herpetología, Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales ‘‘Bernardino Rivadavia’’-CONICET, C1405DJR, Buenos Aires, ARGENTINA 4CIBIO Research Centre in Biodiversity and Genetic Resources, InBIO, Universidade do Porto, Campus Agrário de Vairão, Rua Padre Armando Quintas 7, 4485-661 Vairão, Vila do Conde, PORTUGAL Abstract.—Regarding amphibians, Costa Rica exhibits the greatest species richness per unit area in Middle America, with a total of 215 species reported to date. However, this number is likely an underestimate due to the presence of many unexplored areas that are diffcult to access. Between 2012 and 2017, a monitoring survey of amphibians was conducted in the Central Caribbean of Costa Rica, on the northern edge of the Matama mountains in the Talamanca mountain range, to study the distribution patterns and natural history of species across this region, particularly those considered as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. The results show the highest amphibian species richness among Middle America lowland evergreen forests, with a notable anuran representation of 64 species. -

New Species of Marsupial Frog (Hemiphractidae

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Publications Department of Zoology 6-2011 New Species of Marsupial Frog (Hemiphractidae: Gastrotheca) from an Isolated Montane Forest in Southern Peru Alessandro Catenazzi Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Rudolf von May Florida International University Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/zool_pubs Copyright 2011 Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. Published in Journal of Herpetology, Vol. 45 No. 2 (June 2011). Recommended Citation Catenazzi, Alessandro and von May, Rudolf. "New Species of Marsupial Frog (Hemiphractidae: Gastrotheca) from an Isolated Montane Forest in Southern Peru." (Jun 2011). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Zoology at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Herpetology, Vol. 45, No. 2, pp. 161–166, 2011 Copyright 2011 Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles New Species of Marsupial Frog (Hemiphractidae: Gastrotheca) from an Isolated Montane Forest in Southern Peru 1,2 3 ALESSANDRO CATENAZZI AND RUDOLF vON MAY 1Department of Integrative Biology, University of California at Berkeley, 3060 Valley Life Sciences, Berkeley, California 94720 USA 3Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, Miami, Florida 33199 USA ABSTRACT.—We describe a new species of marsupial frog (genus Gastrotheca) from an isolated patch of cloud forest in the upper reaches of the Pachachaca River, a tributary of the Apurı´mac River in southern Peru (Apurı´mac Region). The new species is small with males less than 30 mm and a single female 35.3 mm in snout–vent length. -

4. DUELLMAN, WE & E. LEHR (2009). Terrestrial-Breeding Frogs

PUBLICATIONS (133 in total) BOOKS & BOOK CONTRIBUTIONS (peer-reviewed*) 4. DUELLMAN, W. E. & E. LEHR (2009). Terrestrial-Breeding Frogs (Strabomantidae) in Peru. Natur- und Tier-Verlag, Naturwissenschaft, Münster, Germany, 382 pp. 3. LEHR, E. (2002). Amphibien und Reptilien in Peru: Die Herpetofauna entlang des 10. Breitengrades von Peru: Arterfassung, Taxonomie, ökologische Bemerkungen und biogeographische Beziehungen. Dissertation, Natur- und Tier-Verlag, Naturwissenschaft, Münster, Germany, 208 pp. 2. *BURKE, L. R., L. S. FORD, E. LEHR, S. MOCKFORD, P. C. H. PRITCHARD, J. P. O. ROSADO, D. M. SENNEKE, AND B. L. STUART (2007). Non-Standard Sources in a Standardized World: Responsible Practice and Ethics of Acquiring Turtle Specimens for Scientific Use, pp. 142– 146. In: SHAFFER, H.B., N. N. FITZSIMMONS, A. GEORGES & A. G.J. RHODIN (eds., 2007): Defining Turtle Diversity: Proceedings of a Workshop on Genetics, Ethics, and Taxonomy of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises. Chelonian Research Monograph 4:1– 200. 1. *LEHR, E. (2005). The Telmatobius and Batrachophrynus (Anura: Leptodactylidae) species of Peru, pp. 39–64. In: E. O. LAVILLA & I. DE LA RIVA, (eds.), Studies on the Andean Frogs of the Genera Telmatobius and Batrachophrynus, Asociación Herpetológica Española, Monografías de Herpetología 7:1–349. SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES (peer-reviewed) 91. CATENAZZI, A., E. LEHR & R. VON MAY (2014): The amphibians and reptiles of Manu National Park and its buffer zone, Amazon basin and eastern slopes of the Andes, Peru. Biota Neotropica 13(4): 269–283. 90. MORAVEC, J., LEHR E., CUSI, J. C., CÓRDOVA, J. H. & V. Gvoždík (2014): A new species of the Rhinella margaritifera species group (Anura, Bufonidae) from the montane forest of the Selva Central, Peru. -

Biobasics Contents

Illinois Biodiversity Basics a biodiversity education program of Illinois Department of Natural Resources Chicago Wilderness World Wildlife Fund Adapted from Biodiversity Basics, © 1999, a publication of World Wildlife Fund’s Windows on the Wild biodiversity education program. For more information see <www.worldwildlife.org/windows>. Table of Contents About Illinois Biodiversity Basics ................................................................................................................. 2 Biodiversity Background ............................................................................................................................... 4 Biodiversity of Illinois CD-ROM series ........................................................................................................ 6 Activities Section 1: What is Biodiversity? ...................................................................................................... 7 Activity 1-1: What’s Your Biodiversity IQ?.................................................................... 8 Activity 1-2: Sizing Up Species .................................................................................... 19 Activity 1-3: Backyard BioBlitz.................................................................................... 31 Activity 1-4: The Gene Scene ....................................................................................... 43 Section 2: Why is Biodiversity Important? .................................................................................... 61 Activity -

Phyllomedusa 13-1.Indd

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Cadernos Espinosanos (E-Journal) Phyllomedusa 13(1):67–70, 2014 © 2014 Departamento de Ciências Biológicas - ESALQ - USP ISSN 1519-1397 (print) / ISSN 2316-9079 (online) doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.11606/issn.2316-9079.v13i1p67-70 SHORT COMMUNICATION Advertisement call of Craugastor noblei: another calling species of the Craugastor gollmeri Group (Anura: Craugastoridae) José Andrés Salazar-Zúñiga 1,2 and Adrían García-Rodríguez 2,3 1 Veragua Rainforest Research Center, Limón, Costa Rica. E-mail: [email protected]. 2 Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica, San Pedro, 11501-2060 San José, Costa Rica. 3 Present address. Laboratório de Biogeografia e Macroecologia, Departamento de Ecologia Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal - RN, Brasil, 59078-900 E-mail: [email protected]. Keywords: advertisement call, calling activity, Costa Rica, vocal sac, vocal slits. Palavras-chave: atividade vocal, canto de anúncio, Costa Rica, fendas vocais, saco vocal. Anuran communication is dominated by Despite this relevance, vocal sacs are absent acoustic signals; consequently, most species in many groups such as the basal genera Alytes, have well-developed vocal systems that can Bombina and Discoglossus (Cannatella 2006), as produce a variety of sounds in different situations well as in more derived groups including some (Duellman and Trueb 1986). The advertisement New World direct-developing frogs. An example call is the most commonly emitted sound in this is the Craugastor gollmeri Group that contains repertoire; males produce this vocalization in seven forest-floor frog species distributed from both reproductive and territorial contexts southern Mexico to Panama (Savage 2002).