George Reedy Interview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

31295005193577.Pdf (3.496Mb)

WARD CARLTON MAYBORN: SILENT GIANT OF THE NEWSPAPER INDUSTRY by JAMES EDMOND CASON, B.S. A THESIS IN MASS COMMUNICATIONS Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved Accepted May, 1987 it\ /:- 90-~ N^, 1' C^' .. ^ TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. HARD TIllES AND THE LAUNCHING OF A CAREER ... 9 III. STARTING THE EVANSVILLE PRESS 16 IV. THE PUBLISHING HOUSE CONCEPT 31 V. MAYBORN LEAVES THE SCRIPPS ORGANIZATION ... 47 VI. STARTING THE CHICAGO SUN 54 VII. MAYBORN RETURNS TO TEXAS 61 VIII. SUMMARY 70 REFERENCES 75 11 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION When Ward Carlton Mayborn was born October 10, 1879, the Civil War had been over for 14 years. The nation was experiencing the problems associated with healing the wounds of war while the age of the industrial revolution was dawning upon the nation. Thomas A. Edison in 1864 invented an automatic telegraph repeater, making possible the sending of mes sages over long distances (1, p. 587). In the early 1870s, less than 10 years before Mayborn's birth, a telegraph system was incorporated into the nation's fledgling railway system (1, p. 587). Edison started to work in his Menlo Park, New Jersey laboratory in 1876 (1, p. 587). It was not until Septem ber 4, 1882, when Mayborn was almost three years old, that New York City got its first electric street lights (2, p. 118) . In his book, The Rise of Industrial America, Page Smith detailed events taking place in the nation at the time of Mayborn's birth and during the next 20 years when Mayborn was receiving all the formal education he was to have and when he found himself, due to economic conditions of the time, looking for work. -

49818 19 1120031

Control Number: 49818 Item Number: 19 Addendum StartPage: 0 VANTAGE POINT ADVISORS, INC. Take aim. 180 State Stieet, Suite 225 Southlake, TX 76092 682 2377126 Greqorv E. Scheiq CFA, CEIV, CP~~JEIVU~FIWCIGX, 21~* www.vpadvlsors com Managing Director- Uti/itie*Pra¢tice Leader 180 State St., Suite 225, Southlake, TX 76092 SAN DIEGO [email protected] LOS ANGELES NEWYORK 214.254.4801 PORFLAND SEATTLE DALLAS EMPLOYMENT HISTORY February 2020 - Present Vantage Point Advisors Managing Director Providing valuation, expert testimony, and financial advisory services. Focus is business valuation, economic damages and forensic accounting testimony. September 2008 - February 2020 ValueScope, Inc. Principal Provided valuation, expert testimony, and financial advisory services with a focus on energy and regulated utility companies. Developed rate of return analyses and valued utility and energy assets. July 2008 - September 2008 Present Value Advisors, LLC Principal Formed Present Value Advisors to provide valuation, litigation support, and financial advisory services. July 2005 - June 2008 Kroll Associates, Inc. Senior Director Performed valuation analyses for transactions, financial reporting, tax, and other management requirements, and provided expert testimony for litigation support. Key focus was in the energy and utility sectors with larger clients. 2002 - July 2005 CBIZ Valuation Group, LLC, Managing Director - Southwest Region Ran the southwest region's valuation practice for approximately three and a half years. In that role, valued many types of businesses, business interests, and professional practices. 1997 - 2002 Deloitte Consulting Senior Manager: Utility Strategy Competency Led projects dealing with utility valuations, mergers and acquisition synergy analyses, real option analyses, strategic assessments, and complex regulatory issues. Served a wide variety of domestic and international clients, including companies in Canada, England, Republic of South Africa, Italy, Scotland, and Singapore. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions Of

February 29, 2016 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E247 SENATE REPUBLICAN SUPPORT OF into the Angus Heritage Foundation, served as to recognize a milestone anniversary in the life OBAMA’S SUPREME COURT NOMI- a member of the American Angus Association of Toledo’s Indiana Avenue Baptist Church. NATION for over 50 years, served as President of the This month the congregation has been cele- Colorado Cattle Feeders, and was presented brating its 70th anniversary with a series of HON. TERRI A. SEWELL with the CSU Leadership in Agriculture Award. special gatherings. I was privileged to join the OF ALABAMA Mr. Houston was involved with a number of congregation yesterday. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES other organizations, where his limitless knowl- Founded by Reverend M. J. Stephenson in edge and service will always be remembered. February 1946, the congregation has been Monday, February 29, 2016 It is the hard work Mr. Houston embodied shepherded by Reverend John Roberts for Ms. SEWELL of Alabama. Mr. Speaker, throughout his life that makes America excep- more than half a century. Pastor Roberts, in today, I rise to urge the Senate Republicans to tional. He has shown true leadership in his in- fact, was part of the organizational meeting of consider President Obama’s Supreme Court dustry and community. I extend my deepest the church. Thus, this long standing beacon in nominee. It is disappointing that our demo- sympathies to Mr. Houston’s family and our city has been blessed with a continuity of cratic process is being so unduly hindered by friends. leadership since its beginnings. -

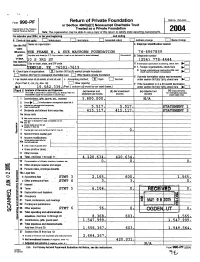

Return of Private Foundation Form 990-PF

Z Foundation OMB No 15450052 Form 990-PF Return of Private or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue Service Note : The organrzafron may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state iepoi 2004 For calendar or tax veer baainnina . and ending Use the IRS Name of organization A Employer identification number label. otherwise, HE FRANK W . & SUE MAYBORN FOUNDATION 74-6067859 print Number and street (a P O box number A mad is not delivered to street address) Room/suite g Telephone number 01type. 10 S 3RD ST 254 778-4444 See specific City or town, state, ZIP code C H exemption application is pending, check here , Instructions . and TEMPLE , TX 76501-7619 D 1. Foreign organizations, check here 1[] 2 . Foreign organizations meehng the 85% test H Check type of organization : ~ Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation check here and anacn ~o~P~canon . ... ..1D Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust = Other taxable private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: [f] Cash ~ Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here 10 (from Part 11, coL (c), line 76) D Other (specify) F If the foundation is to a 60-month termination 15 , 58 2 . 33 9 . (E'~ l~ column (d) must be on cash basis.) under section 507(b)( 1 B check here { / Analysis of Revenue and Expenses (e) Revenue and (6) Net investment (c) Adjusted net (d) Disbursements (The total of amounts in columns (b) (c), and (d) may not for charitable purposes necessarily equal me amounts .n column ~~a~.~ expenses per books income income (cash bay only) 1 Contributions, gifts, grants, etc., received , . -

George Reedy Interview I

LYNDON BAINES JOHNSON LIBRARY ORAL HISTORY COLLECTION LBJ Library 2313 Red River Street Austin, Texas 78705 http://www.lbjlib.utexas.edu/johnson/archives.hom/biopage.asp GEORGE REEDY ORAL HISTORY, INTERVIEW I(b) PREFERRED CITATION For Internet Copy: Transcript, George Reedy Oral History Interview I(b), 12/19/68, by T.H. Baker, Internet Copy, LBJ Library. For Electronic Copy on Compact Disc from the LBJ Library: Transcript, George Reedy Oral History Interview I(b), 12/19/68, by T.H. Baker, Electronic Copy, LBJ Library. GENERAL SERVICES ADMINISTRATION NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS SERVICE Gift of Personal Statement By George Reedy to the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library In accordance with Sec. 507 of the Federal Property and Adminis trative Services Act of 1949, as amended (44 u.s.c. 397) and regulations issued thereunder (41 CFR 101-10), I, ee:o(t'e e, ((Cebt ,hereinafter referred to as the donor, hereby give, donate, and convey to the United States of America for eventual deposit in the proposed Lyndon Baines Johnson Library, and for administration therein by the authorities thereof, a tape and transcript of a personal statement approved by me and prepared for the purpose of deposit in the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library. The gift of this material is made subject to the following terms and conditions: 1. Title to the material transferred hereunder, and all literary property rights, will pass to the United States as of the date of the e 1very of t 1S material into the physical custody of the Archivist of the United States. (~~ ~ v 2. -

The Master of the Senate and the Presidential Hidden Hand: Eisenhower, Johnson, and Power Dynamics in the 1950S by Samuel J

Volume 10 Article 6 2011 The aM ster of the Senate and the Presidential Hidden Hand: Eisenhower, Johnson, and Power Dynamics in the 1950s Samuel J. Cooper-Wall Gettysburg College Class of 2012 Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ghj Part of the Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Cooper-Wall, Samuel J. (2011) "The asM ter of the Senate and the Presidential Hidden Hand: Eisenhower, Johnson, and Power Dynamics in the 1950s," The Gettysburg Historical Journal: Vol. 10 , Article 6. Available at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ghj/vol10/iss1/6 This open access article is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aM ster of the Senate and the Presidential Hidden Hand: Eisenhower, Johnson, and Power Dynamics in the 1950s Abstract In March of 2010, renowned architect Frank Gehry unveiled his design for a memorial to Dwight D. Eisenhower in Washington, D.C. Centered around an elaborate layout of stone blocks running along a city- block of Maryland Avenue is the featured aspect of Gehry‘s design: a narrative tapestry of scenes from Eisenhower‘s life. Over seven stories tall, the tapestry will impede the view of the building located directly behind it. That building is the Department of Education, named for Lyndon Johnson.1 Decades after two of the greatest political titans of the twentieth century had passed away, their legacies were still in competition. -

For Their Eyes Only

FOR THEIR EYES ONLY How Presidential Appointees Treat Public Documents as Personal Property Steve Weinberg THE CENTER FOR PUBLIC INTEGRITY FOR THEIR EYES ONLY How Presidential Appointees Treat Public Documents as Personal Property Steve Weinberg THE CENTER FOR PUBLIC INTEGRITY The Center for Public Integrity is an independent, nonprofit organization that examines public service and ethics-related issues. The Center's REPORTS combine the substantive study of government with in-depth journalism. The Center is funded by foundations, corporations, labor unions, individuals, and revenue from news organizations. This Center study and the views expressed herein are those of the author. What is written here does not necessarily reflect the views of individual members of The Center for Public Integrity's Board of Directors or Advisory Board. Copyright (c) 1992 THE CENTER FOR PUBLIC INTEGRITY. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the written permission of The Center for Public Integrity. ISBN 0-962-90127-X "Liberty cannot be preserved without a general knowledge among the people, who have a right and a desire to know. But, besides this, they have a right, an indisputable, unalienable, indefeasible, divine right to that most dreaded and envied kind of knowledge - I mean of the characters and conduct of their rulers." John Adams (1735-1826), second president of the United States Steve Weinberg is a freelance investigative journalist in Columbia, Mo. From 1983-1990, he served as executive director of Investigative Reporters & Editors, an international organization with about 3000 members. -

Legislative Origins of the National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958

LEGISLATIVE ORIGINS OF THE NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ACT OF 1958 Proceedings of an Oral History Workshop Conducted April 3, 1992 LEGISLATIVE ORIGINS OF THE NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ACT OF 1958 Proceedings of an Oral History Workshop Conducted April 3, 1992 Moderated by John M. Logsdon MONOGRAPHS IN AEROSPACE HISTORY Number 8 National Aeronautics and Space Administration NASA History Office Office of Policy and Plans Washington, DC 1998 Contents Forewor d . .iii Preface and Acknowledgments . .v Introduction . .vii Individual Discussions George E. Reedy . .1 Willis H. Shapley . .6 Gerald W. Siegel . .11 Glen P. Wilson . .16 H. Guyford Stever . .21 Paul G. Dembling . .25 Eilene Galloway . .30 Roundtable Discussion . .37 Appendices “How the U.S. Space Act Came to Be,” by Glen P. Wilson . .49 “Additional Comments,” by Eilene Galloway . .57 “National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958” . .61 Index . .75 Forewor d n retrospect, it appears that the Soviet launch of Sputniks 1 and 2 in the autumn of 1957 took place at exactly the right time to inspire the U.S. entrance into the space age. The ingredients were in place Ito begin space exploration already, but the Sputnik crisis prompted important legislation that brought many of these elements together into a single organization. By striking a blow at U.S. prestige, the Sputnik crisis had the effect of unifying groups that had been working separately on space missions, national defense, arms control, and within national and international organizations. The National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958 was a tangible result of that national unification and accomplished one fundamental objective: it ensured that outer space would be a dependable, orderly place for benefi- cial pursuits. -

Academic Honors & Awards

AUSTIN COLLEGE 2020 ACADEMIC HONORS & AWARDS Austin College President Steven P. O’Day, J.D. Vice President for Academic Affairs and Dean of the Faculty Dr. Elizabeth Gill Honors Convocation 2020 was not convened due to Remote Learning in effect at Austin College for Spring Term 2020 in response to the coronavirus pandemic. President Steven P. O’Day and Dr. Beth Gill, vice president for Academic Affairs and Dean of the Faculty, join together with the entire Austin College community to celebrate in absentia all the award recipients and honorees included in this program. 2 FACULTY RECOGNITION Installation to Faculty Chairs and Professorships The Donald MacGregor Chair in Natural Science ..........................................................................Dr. Ronald David Baker II The Richardson Chair for the Center for Research, Experience & Transformative Education ........ Dr. Lance Frederick Barton The Ray C. Fish Professorship in Mathematics .......................................................................................... Dr. J’Lee Bumpus The Richardson Chair for the Philosophy, Politics, and Economics Program ..................................... Dr. Mark Ronald Hébert The Richardson Chair for the Professionalism and the Humanities Leadership Program .......... Dr. Jennifer Johnson-Cooper The Henry L. and Laura H. Shoap Professorship of English Literature .................................................. Dr. Gregory S. Kinzer The Richardson Chair for the STEM Teaching and Research Leadership Program ........................ -

“Governance by Sound Bite” : the White House Briefing

“Governance by Sound Bite” i: The White House Briefing, Television, and the Modern Presidency ADAM L. SHPEEN Dartmouth College Beginning in 1995, White House Press Briefings conducted by the President’s Press Secretary were televised and broadcasted in their entirety. In this paper, I argue that the decision to televise these briefings was both consequential and unwise. I will first detail the White House Briefings, with a focus on the effect that television has had on the briefings. Next, I will discuss the effect of televised briefings on the nature and function of the Press Secretary and the press. Lastly, I will broaden the analysis of televised briefings to include theories regarding the decline of the Modern Presidency, which are inextricably linked to the rise of television media. I conclude that the advent of televised media causes style to trump substance and deprives the American public of information necessary in the successful operation of democracy Introduction The White House Press Secretary has an important and influential function in the modern White House. Advocating the policies and governing style of the President and the President’s Administration, the Press Secretary must respond to a daily barrage of questions, rumors, and speculations from an over-eager and unafraid White House Press Corps. On a daily basis, the Press Secretary confronts this ferocious pack of reporters at the noontime White House Press Briefing. In 1995, Mike McCurry, then press secretary to President Bill Clinton, decided to allow television cameras to tape the press briefing in its entirety. While this decision may have been considered innocuous at the time, the introduction of cameras into the White House Briefing Room has created an atmosphere of showmanship and theater that has come to characterize today’s White House Briefings. -

George Reedy Oral History Interview III, 6/7/75, by Michael L

LYNDON BAINES JOHNSON LIBRARY ORAL HISTORY COLLECTION LBJ Library 2313 Red River Street Austin, Texas 78705 http://www.lbjlib.utexas.edu/johnson/archives.hom/biopage.asp GEORGE REEDY ORAL HISTORY, INTERVIEW III PREFERRED CITATION For Internet Copy: Transcript, George Reedy Oral History Interview III, 6/7/75, by Michael L. Gillette, Internet Copy, LBJ Library. For Electronic Copy on Compact Disc from the LBJ Library: Transcript, George Reedy Oral History Interview III, 6/7/75, by Michael L. Gillette, Electronic Copy, LBJ Library. GENERAL SERVICES ADMINISTRATION NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS SERVICE Gift of Personal Statement By GEORGE E. REEDY to the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library In accordance with Section 507 of the Federal Property and Administrative Services Act of 1949, as am.ended (44 U. S. C. 397) and regulations issued there under (41 CFR lOl-IO), I. George E. Reedy, hereinafter referred to as the donor, hereby give, donate, and convey to the United States of America for deposit in the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library. and for administration therein by the authorities thereof, a tape and a transcript of a personal statement approved by me and prepared for the purpose of deposit in the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library. The gift of this material is made subject to the following terms and conditions: I. Title to the m.aterial transferred hereunder, and all literary property ri;~hts, will pass to the United States as of the date of the delivery of this material into the physical custody of the Archivist of the United States. 2. It is the donor's wish to make the material donated to the United States of America by terms of this instrument available for research as soon as it has been deposited in the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents About TPA ............................................................................................................................................... 2 Member Services..................................................................................................................................... 2 Board of Directors.................................................................................................................................... 4 TPA Staff ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Newspapers (sorted by city) .................................................................................................................... 6 Directory Cover Contest Finalists ......................................................................................................... 81 Texas Group Newspapers by Ownership .............................................................................................. 83 Newspapers by County ......................................................................................................................... 85 Map of Texas Counties.......................................................................................................................... 85 Associate Members ............................................................................................................................... 89 Texas Newspaper Foundation Hall of Fame Members ........................................................................