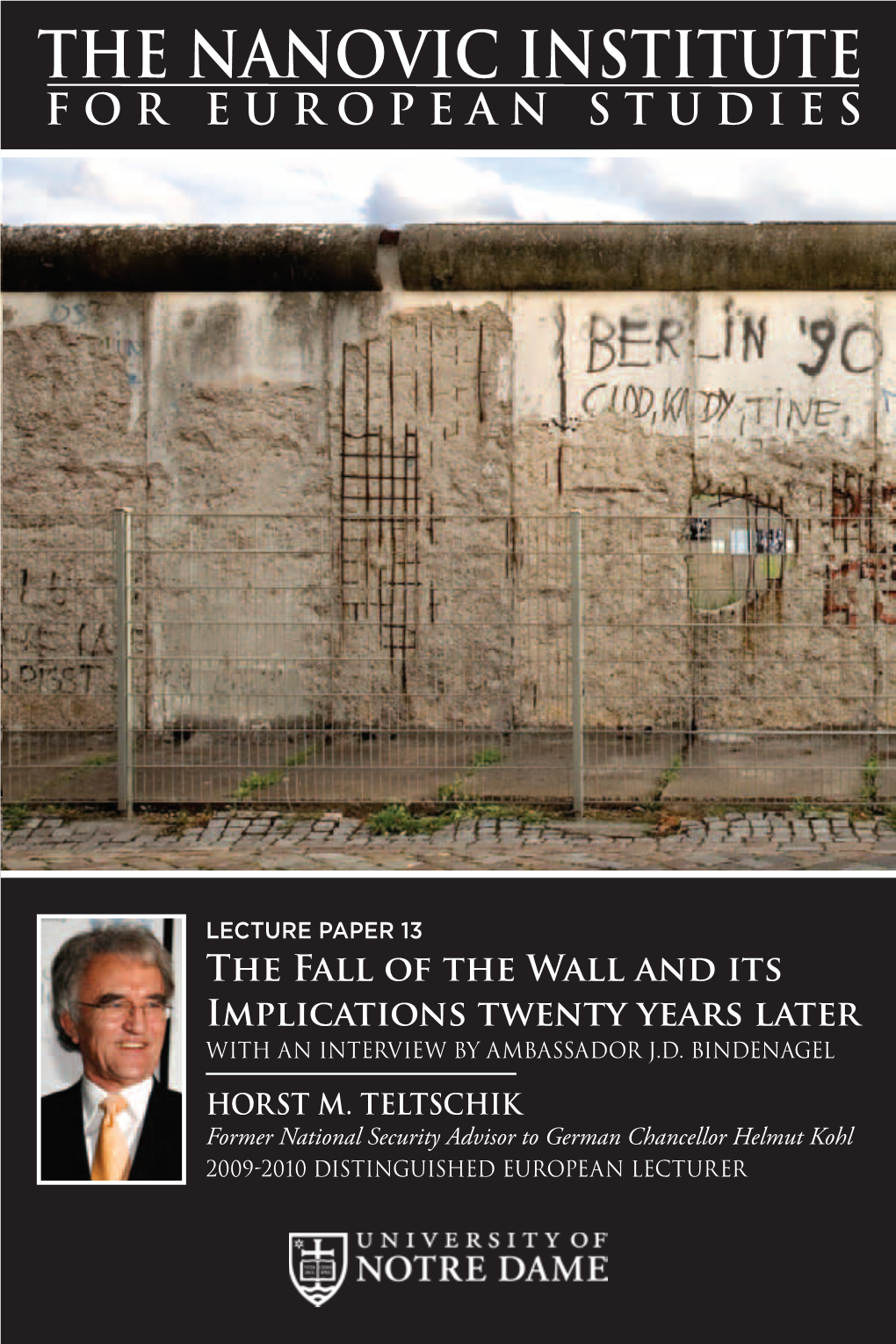

The Fall of the Wall and Its Implications Twenty Years Later with an Interview by Ambassador J.D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

France and the Dissolution of Yugoslavia Christopher David Jones, MA, BA (Hons.)

France and the Dissolution of Yugoslavia Christopher David Jones, MA, BA (Hons.) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia School of History August 2015 © “This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution.” Abstract This thesis examines French relations with Yugoslavia in the twentieth century and its response to the federal republic’s dissolution in the 1990s. In doing so it contributes to studies of post-Cold War international politics and international diplomacy during the Yugoslav Wars. It utilises a wide-range of source materials, including: archival documents, interviews, memoirs, newspaper articles and speeches. Many contemporary commentators on French policy towards Yugoslavia believed that the Mitterrand administration’s approach was anachronistic, based upon a fear of a resurgent and newly reunified Germany and an historical friendship with Serbia; this narrative has hitherto remained largely unchallenged. Whilst history did weigh heavily on Mitterrand’s perceptions of the conflicts in Yugoslavia, this thesis argues that France’s Yugoslav policy was more the logical outcome of longer-term trends in French and Mitterrandienne foreign policy. Furthermore, it reflected a determined effort by France to ensure that its long-established preferences for post-Cold War security were at the forefront of European and international politics; its strong position in all significant international multilateral institutions provided an important platform to do so. -

The End of Détente* a Case Study of the 1980 Moscow Olympics

The End of Détente* A Case Study of the 1980 Moscow Olympics By Thomas Smith After the election of autonomous and must resist all pressure of any Jimmy Carter as US kind whatsoever, whether of a political, religious President, Prime or economic nature.”1 With British government Minister Margaret documents from 1980 recently released under the Thatcher flew to Thirty Year Rule, the time seems apt to evaluate the Washington on 17th debate about the Olympic boycott, and to ask the December 1979 for question: to what extent was the call by the British her first official visit. government for a boycott of the 1980 Moscow Five days later NATO Olympics an appropriate response to the invasion of announced the de- Afghanistan? ployment of a new Before the argument of the essay is established, it generation of American is first necessary to provide a brief narrative of the rockets and Cruise main events. Thatcher’s government began discussing missiles in Western the idea of a boycott in early January 1980; however, Europe. On the 25th their first action was to call for the Olympics to be December Soviet moved to a different location. Once the IOC declared troops marched into that relocating the Olympics was out of the question, Afghanistan. Thatcher told the House of Commons that she was now advising athletes not to go to Moscow and wrote Photo: U.S. Government to Sir Denis Follows, Chairman of the BOA, informing Introduction him of the government’s decision. The BOA, which was Britain’s NOC and the organisation that could During the 1970s, relations between the West and the accept or decline the invitation to the Olympics, Soviet Union were marked by an era of détente. -

The International Community's Role in the Process of German Unification

The International Community’s Role in the Process of German Unification 269 Chapter 10 The International Community’s Role in the Process of German Unification Horst Teltschik The first half of the 20th century was dominated by two world wars with more than 100 million deaths—soldiers and civilians. As a result, from 1945 on Europe was divided. Germany and its capital Berlin lost their sovereignty. Germany was run by the four victorious powers: the United States, France, Great Britain and the Soviet Union. The polit- ical and military dividing line between the three Western powers and the Soviet Union ran through the middle of Germany and Berlin. The world was divided into a bipolar order between the nuclear su- perpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union, with their respec- tive alliance systems NATO and Warsaw Pact. The latter was ruled by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) with its ideological monopoly. In 1945, two militarily devastating world wars were followed by five decades of Cold War. The nuclear arsenals led to a military balance be- tween West and East. The policy of mutual nuclear deterrence did not prevent dangerous political crises—such as the Soviet Berlin Blockade from June 1948 until May 1949, Nikita Khrushchev’s 1958 Berlin Ul- timatum and the 1962 Cuba Crisis—which brought both sides to the brink of another world war. In Berlin, fully armed American and Soviet tanks directly faced each other at Checkpoint Charlie. In Cuba, Soviet missiles threatened to attack the United States. Cold War tensions were compounded by Moscow’s bloody military interventions to crush uprisings against its rule in 1953 in the German Democratic Republic (GDR), in 1956 in Hungary, and 1968 in Prague. -

Interview with J.D. Bindenagel

Library of Congress Interview with J.D. Bindenagel The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR J.D. BINDENAGEL Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: February 3, 1998 Copyright 2002 ADST Q: Today is February 3, 1998. The interview is with J.D. Bindenagel. This is being done on behalf of The Association for Diplomatic Studies. I am Charles Stuart Kennedy. J.D. and I are old friends. We are going to include your biographic sketch that you included at the beginning, which is really quite full and it will be very useful. I have a couple of questions to begin. While you were in high school, what was your interest in foreign affairs per se? I know you were talking politics with Mr. Frank Humphrey, Senator Hubert Humphrey's brother, at the Humphrey Drugstore in Huron, South Dakota, and all that, but how about foreign affairs? BINDENAGEL: I grew up in Huron, South Dakota and foreign affairs in South Dakota really focused on our home town politician Senator and Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey. Frank, Hubert Humphrey's brother, was our connection to Washington, DC, and the center of American politics. We followed Hubert's every move as Senator and Vice President; he of course was very active in foreign policy, and the issues that concerned South Dakota's farmers were important to us. Most of farmers' interests were in their wheat sales, and when we discussed what was happening with wheat you always had to talk about the Russians, who were buying South Dakota wheat. -

Mrs. Thatcher's Return to Victorian Values

proceedings of the British Academy, 78, 9-29 Mrs. Thatcher’s Return to Victorian Values RAPHAEL SAMUEL University of Oxford I ‘VICTORIAN’was still being used as a routine term of opprobrium when, in the run-up to the 1983 election, Mrs. Thatcher annexed ‘Victorian values’ to her Party’s platform and turned them into a talisman for lost stabilities. It is still commonly used today as a byword for the repressive just as (a strange neologism of the 1940s) ‘Dickensian’ is used as a short-hand expression to describe conditions of squalor and want. In Mrs. Thatcher’s lexicon, ‘Victorian’ seems to have been an interchangeable term for the traditional and the old-fashioned, though when the occasion demanded she was not averse to using it in a perjorative sense. Marxism, she liked to say, was a Victorian, (or mid-Victorian) ideo1ogy;l and she criticised ninetenth-century paternalism as propounded by Disraeli as anachronistic.2 Read 12 December 1990. 0 The British Academy 1992. Thanks are due to Jonathan Clark and Christopher Smout for a critical reading of the first draft of this piece; to Fran Bennett of Child Poverty Action for advice on the ‘Scroungermania’ scare of 1975-6; and to the historians taking part in the ‘History Workshop’ symposium on ‘Victorian Values’ in 1983: Gareth Stedman Jones; Michael Ignatieff; Leonore Davidoff and Catherine Hall. Margaret Thatcher, Address to the Bow Group, 6 May 1978, reprinted in Bow Group, The Right Angle, London, 1979. ‘The Healthy State’, address to a Social Services Conference at Liverpool, 3 December 1976, in Margaret Thatcher, Let Our Children Grow Tall, London, 1977, p. -

François Mitterrand, of Germany and France

François Mitterrand, Of Germany and France Caption: In 1996, François Mitterrand, President of France from 1981 to 1995, recalls the negative attitude of Margaret Thatcher, British Prime Minister, towards German reunification. Source: MITTERRAND, François. De l'Allemagne. De la France. Paris: Odile Jacob, 1996. 247 p. ISBN 2- 7381-0403-7. p. 39-44. Copyright: (c) Translation CVCE.EU by UNI.LU All rights of reproduction, of public communication, of adaptation, of distribution or of dissemination via Internet, internal network or any other means are strictly reserved in all countries. Consult the legal notice and the terms and conditions of use regarding this site. URL: http://www.cvce.eu/obj/francois_mitterrand_of_germany_and_france-en- 33ae0d5e-f55b-4476-aa6b-549648111114.html Last updated: 05/07/2016 1/3 François Mitterrand, Of Germany and France […] In Great Britain, on 10 November 1989, the Prime Minister’s Press Office published a statement in which Mrs Thatcher welcomed the lifting of the restrictions on movements of the population of East Germany towards the West, hoped that this would be a prelude to the dismantling of the Berlin Wall, looked forward to the installation of a democratic government in the German Democratic Republic and warned, ‘You have to take these things step by step.’ On the subject of unification, however, she said not a word. Three days later, at the Lord Mayor’s Banquet at the Guildhall in the City of London, she spoke about free elections and a multiparty system in East Germany, cooperation with the emerging democracies of Central Europe and the new role which NATO would have to play. -

I-2014 Infobrief II.Pub

Info-Brief 1/2014 Juni 2014 www.deutsche- stiftung-eigentum.de Liebe Freunde und Förderer der Deutschen Stiftung Eigentum, sehr geehrte Damen und Herren, Prof. Schmidt-Jortzig erhält den „Preis der Deutschen Stiftung Eigentum“ und es erscheinen zwei neue Bände der „Bibliothek des Eigentums“. Im ersten Halbjahr 2014 hat sich viel getan und so geht es auch weiter! Stiftungsrat Bei seiner offiziellen Verabschiedung am 13. Februar 2014 in der Mendelssohn- Vorsitzender: Remise wurde Prof. Schmidt-Jortzig für seine langjährigen Verdienste um die Stiftung Dr. Hermann Otto Solms mit dem „Preis der Deutschen Stiftung Eigentum“ geehrt. In der Laudatio hob Prof. De- Prof. Dr. Otto Depenheuer penheuer die verantwortungsvolle und erfolgreiche Führung der Stiftungsgeschäfte Max Freiherr v. Elverfeldt durch Prof. Schmidt-Jortzig hervor und betonte dessen Engagement für die Idee des Ei- Nicolai Freiherr v. Engelhardt gentums, das für den ersten Stiftungsratsvorsitzenden immer eine Herzensangelegenheit Michael Moritz gewesen ist. Mit einer Festrede zum „Wert des Eigentums“ dankte Prof. Schmidt- Dr. Horst Reinhardt Jortzig für die Auszeichnung und freute sich, die Arbeit der Stiftung weiterhin im Stif- Michael Prinz zu Salm-Salm tungsrat begleiten zu können. Prof. Dr. Edzard Schmidt-Jortzig Gerd Sonnleitner Bernd Ziesemer Wissenschaftlicher Beirat Vorsitzender: Prof. Dr. Otto Depenheuer Vorstand Vorsitzender: N.N. Karoline Beck Wolfgang v. Dallwitz Geschäftsführerin Verbunden mit dem Festakt war die Übergabe des 10. Bandes der Bibliothek des Rechtsanwältin Eigentums „Staatssanierung durch Enteignung“, den der Vizepräsident des Heidrun Gräfin Schulenburg Deutschen Bundestages, Johannes Singhammer, MdB, entgegennahm. Alle Reden und Grußworte anlässlich der Veranstaltung haben wir in der beiliegenden Broschüre festgehalten. Besonders lesenswert – erfreuen Sie sich an den gedruckten Redebeiträgen und Fotos. -

John O. Koehler Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt8d5nd4nw No online items Register of the John O. Koehler papers Finding aid prepared by Hoover Institution Library and Archives Staff Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2009 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Register of the John O. Koehler 2001C75 1 papers Title: John O. Koehler papers Date (inclusive): 1934-2008 Collection Number: 2001C75 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: In German and English Physical Description: 74 manuscript boxes, 1 oversize box, 3 card file boxes(31.1 Linear Feet) Abstract: Correspondence, news dispatches and news stories, photocopies of East German secret police documents, photocopies of United States government documents, post-reunification German governmental reports, clippings, other printed matter, photographs, sound recordings, and video tapes, relating to political conditions in Germany, the East German secret police, the attempted assassination of Pope John Paul II, and Soviet espionage within the Catholic Church. In part, used as research material for the books by J. O. Koehler, Stasi: The Untold Story of the East German Secret Police (Boulder, Colo., 1999), and Spies in the Vatican: The Soviet Union's War against the Catholic Church (2009). Creator: Koehler, John O. Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 2001 Preferred Citation [Identification of item], John O. -

Helmut Kohl, a Giant of the Post-War Era*

DOI: 10.1515/tfd-2017-0025 THE FEDERALIST DEBATE Year XXX, N° 3, November 2017 Comments Helmut Kohl, a Giant of the Post-War Era* Jean-Claude Juncker Today we are saying goodbye to the German the same coin, as he, and Adenauer before and European Statesman, Helmut Kohl. And him, always used to say. I am saying goodbye to a true friend who He made Adenauer’s maxim his own. And he guided me with affection over the years and put it into practice again and again through the decades. I am not speaking now as his thoughts and actions. President of the Commission, but as a friend There are many examples of this. who became President of the Commission. In The fall of the Berlin Wall was greeted with Helmut Kohl, a giant of the post-war era joy throughout Europe and the world. But leaves us; He made it into th ehistory books German reunification – in which he always even while he was still alive – and in those uncompromisingly believed – encountered history books he will forever remain. He was resistance in parts of Europe, and indeed someone who became the continental sometimes outright rejection. monument before which German and Helmut Kohl promoted German reunification European wreaths are laid, and indeed must in many patient conversations. He was able be laid. to do so successfully because his reputation, It was his wish to say goodbye here in which had grown over many years, allowed Strasbourg, this Franco-German, European him to give credible assurances that he border city that was close to his heart. -

KGB Boss Says Robert Maxwell Was the Second Kissinger

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 21, Number 32, August 12, 1994 boss says Robert axwe KGB M ll was the second Kissinger by Mark Burdman On the evening of July 28, Germany's ARD television net Margaret Thatcher, who was frantically trying to prevent work broadcast an extraordinary documentary on the life German reunification. and death of the late Robert Maxwell, the British publishing Stanislav Sorokin was one of several top-level former magnate and sleazy wheeler-and-dealer who died under mys Soviet intelligence and political insiders who freely com terious circumstances, his body found floating in the waters mented on Maxwell during the broadcast. For their own rea off Tenerife in the Canary Islands, on Nov. 5, 1991. The sons, these Russians are evidently intent on provoking an show, "Man Overboard," was co-produced by the firm Mit international discussion of, and investigation into, the mys teldeutscher Rundfunk, headquartered in Leipzig in eastern teries of capital flight operations out of the U.S.S.R. in the Germany, and Austria's Oesterreicher Rundfunk. It relied late 1980s-early 1990s. Former Soviet KGB chief Vladimir primarily on interviews with senior officials of the former Kryuchkov, a partner of Maxwell in numerous underhanded Soviet KGB and GRU intelligence services, who helped ventures who went to jail for his role in the failed August build the case that the circumstances of Maxwell's death 1991 putsch against Gorbachov, suggests in the concluding must have been intimately linked to efforts to cover up sensi moments of the broadcast, that f'the English-American [sic] tive Soviet Communist Party capital flightand capital transfer secret services, who are experienced enough, could, if they to the West in the last days of the U.S.S.R. -

The Economic and Social Policies of German Reunification

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2012 "Sell or Slaughter": The conomicE and Social Policies of German Reunification Saraid L. Donnelly Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Donnelly, Saraid L., ""Sell or Slaughter": The cE onomic and Social Policies of German Reunification" (2012). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 490. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/490 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE “SELL OR SLAUGHTER” THE ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL POLICIES OF GERMAN REUNIFICATION SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR HILARY APPEL AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY SARAID L. DONNELLY FOR SENIOR THESIS FALL 2012 DECEMBER 3, 2012 Abstract This paper looks at the struggles faced by German policymakers in the years following reunification. East Germany struggled with an immediate transformation from a planned economy to a social market economy, while West Germany sent billions of Deutsche Marks to its eastern states. Because of the unequal nature of these two countries, policymakers had to decide on what they would place more emphasis: social benefits for the East or economic protection for the West. The West German state-level, Federal Government and the East German governments struggled in finding multilaterally beneficial policies. This paper looks at the four key issues of reunification: currency conversion, transfer payments, re-privatization, and unemployment. In following the German Basic Law, the policies pursued in terms of these issues tended to place emphasis on eastern social benefits. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. -

June 14, 1989 Conversation Between M. S. Gorbachev and FRG Chancellor Helmut Kohl

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified June 14, 1989 Conversation between M. S. Gorbachev and FRG Chancellor Helmut Kohl Citation: “Conversation between M. S. Gorbachev and FRG Chancellor Helmut Kohl,” June 14, 1989, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Archive of the Gorbachev Foundation, Notes of A.S. Chernyaev. Translated by Svetlana Savranskaya. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/120811 Summary: Gorbachev and Kohl discuss relations with the United States, Kohl's upcoming visit to Poland, and the status of reforms in various socialist countries. Original Language: Russian Contents: English Translation Third Conversation between M. S. Gorbachev and FRG Chancellor Helmut Kohl. June 14, 1989. Bonn (one-on-one). [...] Kohl. We would like to see your visit, Mr. Gorbachev, as the end of the hostility between the Russians and the Germans, as the beginning of a period of genuinely friendly, good-neighborly relations. You understand that these words are supported by the will of all people, by the will of the people who greet you in the streets and the squares. As a Chancellor I am joining this expression of people's will with pleasure, and I am telling you once again that I like your policy, and I like you as a person. Gorbachev. Thank you for such warm words. They are very touching. I will respond with reciprocity, and I will try not to disappoint you. I would like to tell you the following with all sincerity. According to our information, there is a special group charged with the discrediting of perestroika and me personally that was created in the National Security Council of the United States.