Open Thesis - Jeremy David Johnson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hawks Owner Calls Josh Smith 'Closest Thing to Lebron' -- NBA Fanhouse Page 1 of 10

Hawks Owner Calls Josh Smith 'Closest Thing to LeBron' -- NBA FanHouse Page 1 of 10 Shocking New scientific Paying for apnea discovery for discovery fuels treatment? How to joint relief muscle building spend less MAIL You might also like MMA Fighting , Fleaflicker Sign In / Register Main Choose A Sport NFL MLB NBA NHL NCAA Football NCAA Basketball Motorsports Golf Tennis Boxing MMA Women's Basketball Soccer English Premier League Sports Biz & Media Back Porch Cricket Scores And Stats NCAABB Scores MLB Scores NBA Scores NHL Scores NCAABB Women's MLB Stats NBA Stats NHL Stats Writers Fantasy Free Fantasy Games / Check Your Teams Fantasy Main Fantasy Baseball Fantasy Basketball Fantasy Football Latest Player News Forums NFL MLB NBA NHL NCAA Football NCAA Basketball Motorsports Golf Tennis Soccer Boxing MMA Fantasy Shop http://nba.fanhouse.com/2010/04/21/hawks-owner-calls-josh-smith-closest-thing-to-lebron/ 4/21/2010 Hawks Owner Calls Josh Smith 'Closest Thing to LeBron' -- NBA FanHouse Page 2 of 10 Tickets NFL Gear NBA Jerseys College Apparel FanShop Search Sports News NBA Home Scores Standings Stats Teams EASTERN CONFERENCE Atlantic Division Boston Celtics New Jersey Nets New York Knicks Philadelphia 76ers Toronto Raptors Southeast Division Atlanta Hawks Charlotte Bobcats Miami Heat Orlando Magic Washington Wizards Central Division Chicago Bulls Cleveland Cavaliers Detroit Pistons Indiana Pacers Milwaukee Bucks WESTERN CONFERENCE Northwest Division Denver -

George W. Bush Evaluating the President at Midterm

George W. Bush Evaluating the President at Midterm EDITED BY Bryan Hilliard Tom Lansford Robert P. Watson George W. Bush SUNY series on the Presidency: Contemporary Issues John Kenneth White, editor George W. Bush Evaluating the President at Midterm Edited By Bryan Hilliard, Tom Lansford, Robert P.Watson State University of New York Press Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2004 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, address State University of New York Press, 90 State Street, Suite 700, Albany, NY 12207 Production by Michael Haggett Marketing by Susan M. Petrie Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data George W. Bush: evaluating the president at midterm/edited by Bryan Hilliard, Tom Lansford, and Robert P.Watson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7914-6133-5 (hardcover: alk. paper—ISBN 0-7914-6134-3 (pbk.: alk. paper) 1. Bush, George W. (George Walker), 1946– 2. United States—Politics and government—2001. I. Hilliard, Bryan, 1957– II. Lansford, Tom. III. Watson, Robert P.,1963– E903.G465 2005 973.931Ј092—dc22 2004008538 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 For Brenda, Amber, and Claudia— With all our love and admiration Contents Preface ix Introduction 1 Robert P.Watson, Bryan Hilliard, and Tom Lansford Part 1 Leadership and Character 17 Chapter 1 The Arbiter of Fate: The Presidential Character of George W. -

Public Commentary 1-31-17

Stanley Renshon Public Affairs/Commentary-February 2017 I: Commentary Pieces/Op Ed Pieces 33. “Will Mexico Pay for Trump’s Wall?” [on-line debate, John S. Kierman ed], February 16, 2017. https://wallethub.com/blog/will-mexico-pay-for-the- wall/32590/#stanley-renshon 32. “Psychoanalyst to Trump: Grow up and adapt,” USA TODAY, June 23, 2106. http://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2016/06/23/trump-psychoanalyst- grow-up-adapt-column/86181242/ 31. “9/11: What would Trump Do?,” Politico Magazine, March 31, 2016. http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2016/03/donald-trump-2016-terrorist- attack-foreign-policy-213784 30. “You don't know Trump as well as you think,” USA TODAY, March 25, 2106. http://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2016/03/25/donald-trump-narcissist- business-leadership-respect-column/82209524/ 29. “Some presidents aspire to be great, more aspire to do well’ essay for “The Big Idea- Diagnosing the Urge to Run for Office,” Politico Magazine, November/December 2015. http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2015/10/2016-candidates-mental- health-213274?paginate=false 28. “Obama’s Place in History: Great, Good, Average, Mediocre or Poor?,” Washington Post, February 24, 2014. http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/monkey-cage/wp/2014/02/24/obamas- place-in-history-great-good-average-mediocre-or-poor/ 27. President Romney or President Obama: A Tale of Two Ambitions, Montreal Review, October 2012. http://www.themontrealreview.com/2009/President-Romney-or-President- Obama-A-Tale-of-Two-Ambitions.php 26. America Principio, Por Favor, Arizona Daily Star, July 1, 2012. http://azstarnet.com/news/opinion/guest-column-practice-inhibits-forming-full- attachments-to-us/article_10009d68-0fcc-5f4a-8d38-2f5e95a7e138.html 25. -

Bae Institute Crafts Magical Photonic Laser Thruster -- Engadget Page 1 of 5

Bae Institute crafts magical photonic laser thruster -- Engadget Page 1 of 5 Free Switched iPhone app - try it now! MAIL KIN ONE AND TWO IPHONE OS 4 APPLE IPAD HTC EVO 4G WINDOWS PHONE 7 THE ENGADGET SHOW Misc. Gadgets, Bae Institute crafts magical photonic laser thruster By Darren Murph posted Feb 24th 2007 12:05PM Now that humans have shot themselves up into space, frolicked on the moon, and have their own space station just chillin' in the middle of the galaxy, what's really left to accomplish out there? How about cruising around at light speed? Apparently, a boastful group of scientists at the Bae Institute in Southern California feel that they're one step closer to achieving the impossible, as the "world's first photonic laser thruster" was purportedly demonstrated. Using a photonic laser and a sophisticated photon beam amplification system, Dr. Bae reportedly "demonstrated that photonic energy could generate amplified thrust between two spacecraft by bouncing photons many thousands of times between them." The Photonic Laser Thruster (PLT) was constructed with off-the-shelf parts and a bit of fairy dust, and it's said that this invention could eliminate the need for "other propellants" on a wide range of NASA spacecrafts, theoretically savings millions on energy costs and enabling longer missions. So CubeSail parachute to drag old while this may be an incredibly novel idea, the chances of this actually working outside of a laboratory satellites from orbit, keep seem relatively small, and make sure we're not the guinea pigs strapped -

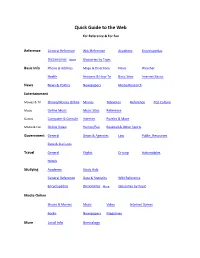

Quick Guide to the Web

Quick Guide to the Web For Reference & For Fun Reference General Reference Wiki Reference Academic Encyclopedias Dictionaries More Glossaries by Topic Basic Info Phone & Address Maps & Directions News Weather Health Answers & How-To Basic Sites Internet Basics News News & Politics Newspapers Media Research Entertainment Movies & TV Shows/Movies Online Movies Television Reference Pop Culture Music Online Music Music Sites Reference Games Computer & Console Internet Puzzles & More Media & Fun Online Video Humor/Fun Baseball & Other Sports Government General Depts & Agencies Law Public_Resources Data & Statistics Travel General Flights Driving Automobiles Hotels Studying Academic Study Aids General Reference Data & Statistics Wiki Reference Encyclopedias Dictionaries More Glossaries by Topic Media Online Shows & Movies Music Video Internet Games Books Newspapers Magazines More Local Info Genealogy Finding Basic Information Basic Search & More Google Yahoo Bing MSN ask.com AOL Wikipedia About.com Internet Public Library Freebase Librarian Chick DMOZ Open Directory Executive Library Web Research OEDB LexisNexis Wayback Machine Norton Site-Checker DigitalResearchTools Web Rankings Alexa Web Tools - Librarian Chick Web 2.0 Tools Top Reference & Resources – Internet Quick Links E-map | Indispensable Links | All My Faves | Joongel | Hotsheet | Quick.as Corsinet | Refdesk Tools | CEO Express Internet Resources Wayback Machine | Alexa | Web Rankings | Norton Site-Checker Useful Web Tools DigitalResearchTools | FOSS Wiki | Librarian Chick | Virtual -

While Others Stumble, Hawks Soar -- NBA Fanhouse Page 1 of 10

While Others Stumble, Hawks Soar -- NBA FanHouse Page 1 of 10 MAIL You might also like MMA Fighting , Fleaflicker Sign In / Register Main Choose A Sport NFL MLB NBA NHL NCAA Football NCAA Basketball Motorsports Golf Tennis Boxing MMA Women's Basketball Soccer English Premier League Sports Biz & Media Back Porch Cricket Scores And Stats NCAABB Scores MLB Scores NBA Scores NHL Scores NCAABB Women's MLB Stats NBA Stats NHL Stats Writers Jay Mariotti Kevin Blackistone Lisa Olson Greg Couch Terence Moore David Whitley Thomas George All FanHouse Writers Fantasy 2010 Bracket Challenge Free Fantasy Games / Check Your Teams Fantasy Main Fantasy Baseball Fantasy Basketball Fantasy Football Latest Player News Forums NFL MLB NBA NHL NCAA Football http://nba.fanhouse.com/2010/04/19/while-others-stumble-hawks-soar/ 4/19/2010 While Others Stumble, Hawks Soar -- NBA FanHouse Page 2 of 10 NCAA Basketball Motorsports Golf Tennis Soccer Boxing MMA Fantasy Shop Tickets NFL Gear NBA Jerseys College Apparel FanShop Search Sports News NBA Home Scores Standings Stats Teams EASTERN CONFERENCE Atlantic Division Boston Celtics New Jersey Nets New York Knicks Philadelphia 76ers Toronto Raptors Southeast Division Atlanta Hawks Charlotte Bobcats Miami Heat Orlando Magic Washington Wizards Central Division Chicago Bulls Cleveland Cavaliers Detroit Pistons Indiana Pacers Milwaukee Bucks WESTERN CONFERENCE Northwest Division Denver Nuggets Minnesota Timberwolves Oklahoma City -

The Reconstruction of American Journalism

The Reconstruction of American Journalism A report by Leonard Downie, Jr. Michael Schudson Vice President at Large Professor The Washington Post Columbia University Professor, Arizona State University Graduate School of Journalism October 20, 2009 The Reconstruction of American Journalism By Leonard Downie, Jr. and Michael Schudson American journalism is at a transformational moment, in which the era of dominant newspapers and influential network news divisions is rapidly giving way to one in which the gathering and distribution of news is more widely dispersed. As almost everyone knows, the economic foundation of the nation’s newspapers, long supported by advertising, is collapsing, and newspapers themselves, which have been the country’s chief source of independent reporting, are shrinking— literally. Fewer journalists are reporting less news in fewer pages, and the hegemony that near-monopoly metropolitan newspapers enjoyed during the last third of the twentieth century, even as their primary audience eroded, is ending. Commercial television news, which was long the chief rival of printed newspapers, has also been losing its audience, its advertising revenue, and its reporting resources. Newspapers and television news are not going to vanish in the foreseeable future, despite frequent predictions of their imminent extinction. But they will play diminished roles in an emerging and still rapidly changing world of digital journalism, in which the means of news reporting are being reinvented, the character of news is being reconstructed, -

Dark Excitons Could Light up Your Quantum Computer, Life -- Engadget Page 1 of 4

Dark excitons could light up your quantum computer, life -- Engadget Page 1 of 4 Watch Gadling TV's "Travel Talk" and get all the latest travel news! MAIL You might also like: Engadget HD , Engadget Mobile and More GALAXY TAB REVIEW WP 7 REVIEW KINECT REVIEW GOOGLE TV REVIEW MACBOOK AIR REVIEW NOOK COLOR Science Dark excitons could light up your quantum computer, life By Tim Stevens posted Nov 18th 2010 10:09AM Yeah, we're still hanging around playing Q*bert and waiting on folks to get those qubits a spinning. Meanwhile, researchers have found a new path to follow on the way to quantum enlightenment. A new, darker path, which entails the use of so-called dark excitons as quantum bits. While doubling as a great name for future robo-gigolos, a dark exciton is an electron-hole pair with parallel spins. The parallel spin, which makes this quasiparticle "dark," also enables it to be long-lasting and, critically, to be excited with an electrical charge to set its state, a state that can then be read by looking for an emitted photon. Fascinating? Absolutely. Coming to a desktop near you? Not likely -- not unless your desktop is kept at a temperature of 4.2K, anyway. Sony sees RED with PMW-F3 [Image credit: Smite-Meister ] camera, we go hands-on with the $16k "indie" (video) ars technica 1 hour ago Nature Physics 195 36 The Windows PC ClickPad finally improved? Synaptics ClickPad IS Series 3 preview dark exciton , DarkExciton , electron hole pair , ElectronHolePair , exciton , quantum computer , quantum 3 hours ago state , QuantumComputer , QuantumState , qubit , research Motorola Defy review 6 hours ago Login below to leave a comment: The Engadget Show returns Saturday, November 20th with Sprint's product chief, Google Add New Comment Powered by TV's lead dev, and giveaways Type your comment here. -

Peyton a Double Agent? Some Think So -- NFL Fanhouse

MAIL You might also like MMA Fighting, Fleaflicker Sign In / Register Main Choose A Sport NFL MLB NBA NHL NCAA Football NCAA Basketball Motorsports Golf Tennis Boxing MMA Women's Basketball Soccer English Premier League Sports Biz & Media Back Porch Cricket Scores And Stats NCAABB Scores MLB Scores NBA Scores NHL Scores NCAABB Women's MLB Stats NBA Stats NHL Stats Writers Jay Mariotti Kevin Blackistone Lisa Olson Greg Couch Terence Moore David Whitley Thomas George All FanHouse Writers Fantasy 2010 Bracket Challenge Free Fantasy Games / Check Your Teams Fantasy Main Fantasy Baseball Fantasy Basketball Fantasy Football Latest Player News Forums NFL MLB NBA NHL NCAA Football NCAA Basketball Motorsports Golf Tennis Soccer Boxing MMA Fantasy Shop Tickets NFL Gear NBA Jerseys College Apparel FanShop Search Sports News NFL Home Scores & Schedules Standings Stats Teams AFC EAST Buffalo Bills Miami Dolphins New England Patriots New York Jets WEST Denver Broncos Kansas City Chiefs Oakland Raiders San Diego Chargers NORTH Baltimore Ravens Cincinnati Bengals Cleveland Browns Pittsburgh Steelers SOUTH Houston Texans Indianapolis Colts Jacksonville Jaguars Tennessee Titans NFC EAST Dallas Cowboys New York Giants Philadelphia Eagles Washington Redskins WEST Arizona Cardinals San Francisco 49ers Seattle Seahawks St. Louis Rams NORTH Chicago Bears Detroit Lions Green Bay Packers Minnesota Vikings SOUTH Atlanta Falcons Carolina Panthers New Orleans Saints Tampa Bay Buccaneers Players Player Position Team Transactions Injuries Tickets Live Odds NFL Gear Super Bowl Indianapolis Colts New Orleans Saints FanHouse TV Super Bowl Ads Miami Moments Peyton a Double Agent? Some Think So 871Comments Say Something » 2/22/2010 6:40 PM ET By Terence Moore PrintAText Size E-mail More Terence Moore Terence Moore is a national columnist for FanHouse INDIANAPOLIS -- It's been a couple of weeks since the Indianapolis Colts suffered that come-from-ahead loss in the Super Bowl. -

USC Dornsife in the News Archive - 2010

USC Dornsife in the News Archive - 2010 December December 17, 2010 to January 3, 2011 The Washington Post ran an op-ed by Dan Schnur, director of the Unruh Institute of Politics, offering political predictions for the coming year. The Wall Street Journal quoted Stanley Rosen of political science about Christian Bale’s ability to draw movie audiences in China with an upcoming Zhang Yimou film. The Washington Post highlighted research by Michael Messner of sociology and colleagues at the USC Center for Feminist Research, which found that ESPN’s “SportsCenter” devoted only 1.4 percent of its 2009 coverage to female athletes or games. Thursday, December 16, 2010 The Chronicle of Higher Education, in its Tech Talk Therapy podcast series, featured a writing class led by Mark Marino of the USC College in which students spent the fall semester creating online tools and resources for victims of cyberbullies. The Washington Post, in an Associated Press story, featured the expertise of Janet Hoskins of anthropology in a story about the struggle to preserve the ancient traditions of Cao Dai that Vietnamese refugees brought with them to the U.S. VentureBeat quoted Robert Vos of the USC College about greener packaging being used by merchants for shipping gifts during the holidays. Wednesday, December 15, 2010 U.S. News and World Report featured research by Richard Easterlin, university professor and professor of economics. The study found that raising a country from poverty to affluence doesn’t make the nation’s population happier. The Los Angeles Times ran an obituary for educational filmmaker J. -

Downsizing Democracy Crenson, Matthew A., Ginsberg, Benjamin

Downsizing Democracy Crenson, Matthew A., Ginsberg, Benjamin Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Crenson, Matthew A. and Benjamin Ginsberg. Downsizing Democracy: How America Sidelined Its Citizens and Privatized Its Public. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.72712. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/72712 [ Access provided at 25 Sep 2021 15:31 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. HOPKINS OPEN PUBLISHING ENCORE EDITIONS Matthew A. Crenson and Benjamin Ginsberg Downsizing Democracy How America Sidelined Its Citizens and Privatized Its Public Open access edition supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. © 2019 Johns Hopkins University Press Published 2019 Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. CC BY-NC-ND ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-3068-3 (open access) ISBN-10: 1-4214-3068-1 (open access) ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-3067-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-4214-3067-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-3735-4 (electronic) ISBN-10: 1-4214-3735-X (electronic) This page supersedes the copyright page included in the original publication of this work. Downsizing Democracy Downsizing Democracy How America Sidelined Its Citizens and Privatized Its Public Matthew A. Crenson Benjamin Ginsberg The Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore and London © The Johns Hopkins University Press All rights reserved. -

Robotic Surgical Simulator Lets Doctors Sharpen Their Skills by Operating on Polygons -- E

Robotic Surgical Simulator lets doctors sharpen their skills by operating on polygons -- E... Page 1 of 3 Free Switched iPhone app - try it now! MAIL You might also like: Engadget HD, Engadget Mobile and More FEATURES: THE ENGADGET SHOW ENGADGET AWARDS WINDOWS PHONE 7 SERIES APPLE IPAD NEXUS ONE REVIEW ENGADGET APPS Robots, Science Robotic Surgical Simulator lets doctors sharpen their skills by operating on polygons By Tim Stevens posted Feb 26th 2010 9:43AM These days you wouldn't jump behind the controls of a real plane without logging a few hours on the simulator, and so we're glad to hear that doctors no longer have to grab the controls of a da Vinci surgical robot without performing some virtual surgeries first. The Center for Robotic Surgery at Roswell Park Cancer Institute and the University of Buffalo School of Engineering have collaborated to create RoSS, the Robotic Surgical Simulator. Unlike our Ross, who works odd hours and covers fuel cell unveils with innate skill, this RoSS allows doctors to slice and dice virtual patients without worrying about any messy cleanups -- or messy lawsuits. We're guessing it'll be awhile before consumer versions hit the market, but just in case we've gone ahead and put our pre-orders in for the prostate expansion to Microsoft Cutting Sim 2014™. PhysOrg Buffalo.edu 28 Sagem Orga's SIMFi merges WiFi with SIM cards at long last, buffalo, center for robotic surgery, center for robotic surgery at roswell park cancer institute, turns any phone into a hotspot CenterForRoboticSurgery, CenterForRoboticSurgeryAtRoswellParkCancerInstitute,