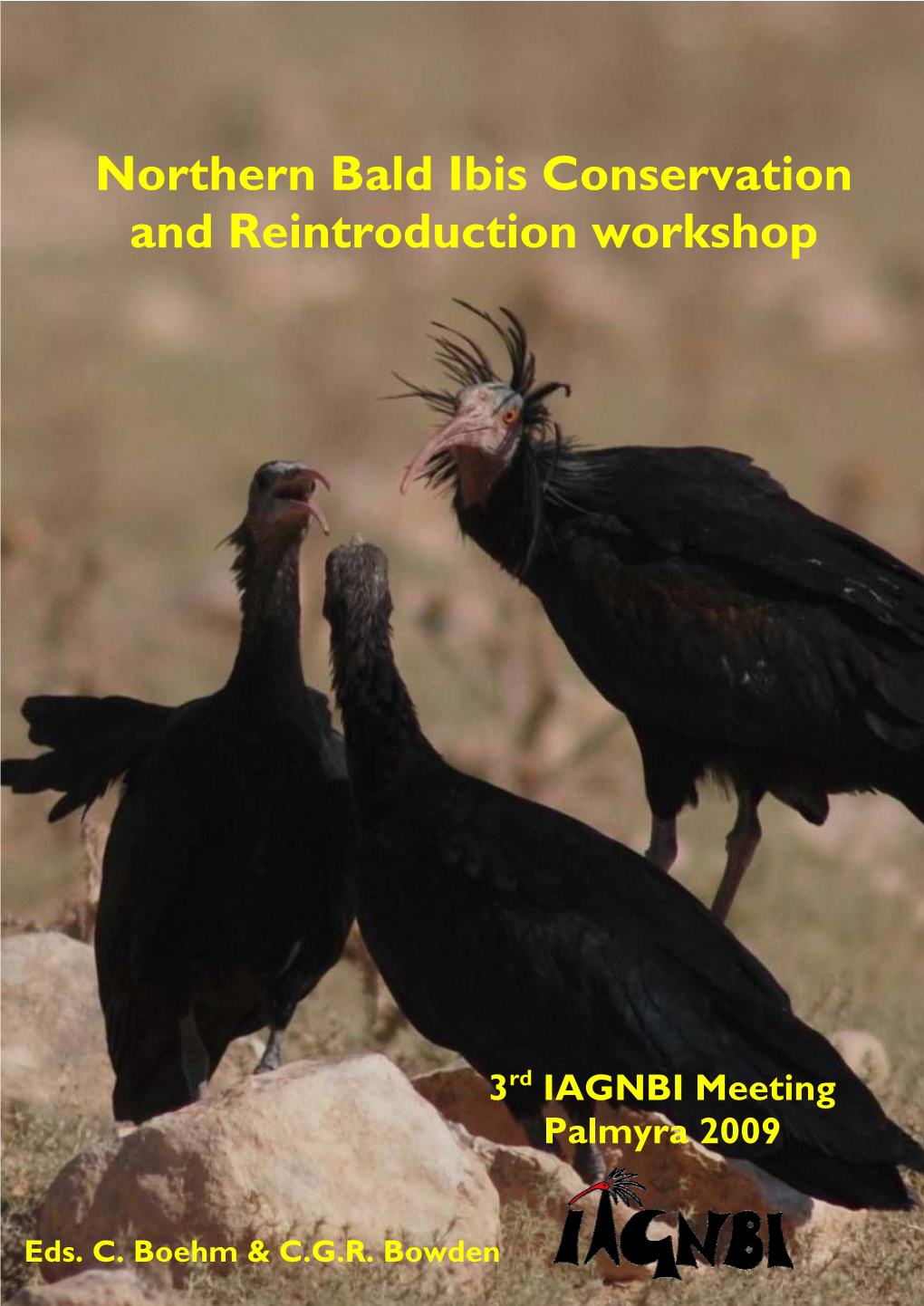

Palmyra Workshop Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Satellite Tracking Reveals the Migration Route and Wintering Area of the Middle East Population of Critically Endangered Northern Bald Ibis Geronticus Eremita

Satellite tracking reveals the migration route and wintering area of the Middle East population of Critically Endangered northern bald ibis Geronticus eremita J eremy A. Lindsell,Gianluca S erra,Lubomir P ESˇ KE,Mahmoud S. Abdullah G hazy al Q aim,Ahmed K anani and M engistu W ondafrash Abstract Since its discovery in 2002 the small colony of coastline in Morocco now subject to intensive conservation northern bald ibis Geronticus eremita in the central Syrian management. A Middle Eastern population was thought desert remains at perilously low numbers, despite good extinct since 1989 (Arihan, 1998), and extinct in Syria since productivity and some protection at their breeding grounds. the late 1920s (Safriel, 1980), part of a broad long-term The Syrian birds are migratory and return rates of young decline in this species (Kumerloeve, 1984). Unlike the birds appear to have been poor but because the migration relatively sedentary Moroccan birds, the eastern population route and wintering sites were unknown little could be was migratory (Hirsch, 1979) but the migration routes and done to address any problems away from Syria. Satellite wintering sites were unknown. The discovery of a colony of tracking of three adult birds in 2006–2007 has shown they northern bald ibises in Syria in 2002 (Serra et al., 2003) migrate through Jordan, Saudi Arabia and Yemen to the confirmed the survival of this migratory population. The central highlands of Ethiopia. The three tagged birds and Syrian birds arrive in the breeding area in February and one other adult were found at the wintering site but none depart in July. -

Flocking of V-Shaped and Echelon Northern Bald Ibises with Different Wingspans: Repositioning and Energy Saving

Flocking of V-shaped and Echelon Northern Bald Ibises with Different Wingspans: Repositioning and Energy Saving Amir Mirzaeinia1, Mehdi Mirzaeinia2, Mostafa Hassanalian3* V-shaped and echelon formations help migratory birds to consume less energy for migration. As the case study, the formation flight of the Northern Bald Ibises is considered to investigate different effects on their flight efficiency. The effects of the wingtip spacing and wingspan are examined on the individual drag of each Ibis in the flock. Two scenarios are considered in this study, (1) increasing and (2) decreasing wingspans toward the tail. An algorithm is applied for replacement mechanism and load balancing of the Ibises during their flight. In this replacing mechanism, the Ibises with the highest value of remained energy are replaced with the Ibises with the lowest energy, iteratively. The results indicate that depending on the positions of the birds with various sizes in the flock, they consume a different level of energy. Moreover, it is found that also small birds have the chance to take the lead during the flock. I. Introduction There are 1800 species of birds that migrate through seasonal long-distance routes from hundreds up to several thousand kilometers1. For example, Bar-tailed godwits as one of the non-stop migratory birds travel for 11600 km1,2. Canada Geese with an average speed of about 18 m/s migrate for 3,200 to 4,800 Km in a single day if the weather is good44. The Arctic terns migrate from the Arctic to the Antarctic1. Besides the mentioned migratory birds, other bird species including pelicans, swans, cormorants, cranes, and Ibis migrate in an echelon or V-shaped formations1. -

The Northern Bald Ibis from Ancient Egypt to the Presence

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.25.397570; this version posted November 26, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 How human intervention and climate change shaped the fate 2 of the Northern Bald Ibis from ancient Egypt to the presence: 3 an interdisciplinary approach to extinction and recovery of an 4 iconic bird species 5 6 Johannes Fritz1,2*, Jiří Janák3 7 1 Waldrappteam Conservation & Research, Mutters, Austria 8 2 Department of Behavioral and Cognitive Biology, University of Vienna, Austria 9 3 Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic 10 11 *Corresponding author 12 E-mail: [email protected] (JF) 13 14 Both authors contributed equally to this work. 15 16 Abstract 17 Once widespread around the Mediterranean, the Northern Bald Ibis (Geronticus eremita) became one 18 of the rarest birds in the world. We trace the history of this species through different epochs to the 19 present. A particular focus is on its life and disappearance in ancient Egypt, where it attained the 20 greatest mythological significance as a hieroglyphic sign for ‘blessed ancestor spirits’, and on modern 21 endeavours to rewild and restore the species. The close association of the Northern Bald Ibis with 22 human culture in ancient Egypt, as in other regions, is caused by primarily two reasons, the 23 characteristic appearance and behaviour, as well as the need for open foraging areas. -

Since Four Year a Team of Biologists and Pilots Work on A

Mutters, 12. 2. 2006 Dear friend of the project Waldrappteam.at I am happy to inform you about a further successful year of our project. We brought a second group of birds to the Tuscany. Both groups are together now; they are free-flying and feed on their own. Beside we had again different activities. In Burghausen, Bavaria, we carried out a study on feeding-ecology with a free-flying group of one year old birds. The birds attracted lots of local people, just as our exhibition did, which was first placed in the Museum INATURA in Dornbirn, Vorarlberg, and later on in the Zoo Schmiding, Upper Austria. A group of six birds, hand-raised in the Zoo Schmiding during the exhibition, flew free during summer near Waidhofen a.d. Thaya, Lower Austria, and were then integrated into the local Waldrapp group placed in a spacious aviary. A great success was the behaviour of the seven birds, which fly free in Italy since April 2005. These birds behave ‘biologically meaningful’ just as juvenile migratory birds are expected to do. They have proper distance to humans, they feed independent, and they seem to have knowledge about the migration route. None of these birds got lost yet. After this summer Dipl.Biol. Alexandra Wolf left the project. For year she was a very relevant member of the team. Thanks a lot! I also thank all the sponsors and supporters as well as all the people, whose interest and enthusiasm motivated us a lot. With best wishes Johannes Fritz Project leader Waldrappteam.at Literature cited - 14 - Indroduction - 3 - Articles and presentations 2005 17 Autumn Migration 04 - 6 - Vernal migration 2005 - 6 - Autumn Migration 2005 - 7 - Responsible for the content:: Wintering at the Laguna 2005/06 - 7 - Dr. -

ISSAP Northern Bald Ibis

TECHNICAL SERIES No. 55 International Single Species Action Plan for the Conservation of the Northern Bald Ibis Geronticus eremita Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA) International Single Species Action Plan for the Conservation of the Northern Bald Ibis Geronticus eremita Revision 1 AEWA Technical Series No. 55 November 2015 Produced by The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), United Kingdom BirdLife International Prepared with financial support from The Saudi Wildlife Authority (SWA), Saudi Arabia Jazan University, Saudi Arabia Compiled by: Chris Bowden Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), The Lodge, Sandy, Bedfordshire, SG19 2DL, United Kingdom Email: [email protected] Contributors: Muhannad Abutarab (Syria), Mohammad Al-Salamah (Saudi Arabia), HHP Bandar bin Saud bin Mohammad Al-Saud (Saudi Arabia), Ruba Alssarhan (Syria), Nabegh Ghazal Asswad (Syria), Christiane Boehm (International Advisory Group for the Northern Bald Ibis [IAGNBI] expert), Chris Bowden (Coordinator), Sergey Dereliev (UNEP/AEWA Secretariat), George Eshiamwata (BirdLife Africa),Mihret Ewnetu (Ethiopia), Amina Fellous (IAGNBI Algeria), Johannes Fritz (IAGNBI Austria), Hamida Salhi (Algeria), Jaber Harise (Saudi Arabia), Taner Hatipoglu (Turkey), Sureyya Cevat Isfendiyaroglu (Turkey), Sharif Al Jbour (Eastern regional co-coordinator), Mike Jordan (IAGNBI South Africa) Omar Al Khushaim (Saudi Arabia), Nina Mikander (UNEP/AEWA Secretariat), Moulay Melliani Khadidja (Algeria), José Manuel López (Spain), Yousuf Mohageb (Yemen), Noaman Mohamed (Morocco), Ammar Momen (Saudi Arabia), Rubén Moreno-Opo (Spain), Widade Oubrou (Morocco), Jorge Fernandez Orueta (Western regional co-coordinator), Lubomir Peske (IAGNBI expert), Miguel Angel Quevedo (IAGNBI Spain), Roger Safford (BirdLife International), Gianluca Serra (IAGNBI expert), Rob Sheldon (Independent), Mohammed Shobrak (Saudi Arabia), Dawit Tesfai (Eritrea), Zafar Ul Islam (Saudi Arabia), Can Yeniyurt (Turkey), Yacob Yohannes (Eritrea), Fehmi Yuksel (Turkey). -

IAGNBI Conservation and Reintroduction Workshop

NNNooorrrttthhheeerrrnnn BBBaaalllddd IIIbbbiiisss CCCooonnnssseeerrrvvvaaatttiiiooonnn aaannnddd RRReeeiiinnntttrrroooddduuuccctttiiiooonnn WWWooorrrkkkssshhhoooppp IIIAAAGGGNNNBBBIII MMMeeeeeetttiiinnnggg IIInnnnnnsssbbbrrruuuccckkk --- 222000000333 EEEdddsss... CCC...BBBoooeeehhhmmm,,, CCC...BBBooowwwdddeeennn &&& MMM...JJJooorrrdddaaannn Northern Bald Ibis Conservation and Reintroduction Workshop Proceedings of the International Advisory Group for the Northern Bald Ibis (IAGNBI) meeting Alpenzoo Innsbruck – Tirol, July 2003. Editors: Christiane Boehm Alpenzoo Innsbruck-Tirol Weiherburggasse 37a A-6020 Innsbruck Austria [email protected] Christopher G.R. Bowden RSPB, International Research The Lodge Sandy Bedfordshire. SG19 2DL United Kingdom [email protected] Mike J.R. Jordan North of England Zoological Society Chester Zoo Chester. CH2 1LH United Kingdom [email protected] September 2003 Published by: RSPB The Lodge, Sandy Bedfordshire UK Cover picture: © Mike Jordan ISBN 1-901930-44-0 Northern Bald Ibis Conservation and Reintroduction Workshop Proceedings of the International Advisory Group for the Northern Bald Ibis (IAGNBI) meeting Alpenzoo Innsbruck – Tirol, July 2003. Eds. Boehm, C., Bowden, C.G.R. & Jordan M.J.R. Contents Introduction …………………………………………………………………… 1 Participants ……………………………………………………………………. 3 IAGNBI role and committee …………………………………………………... 8 Conservation priorities ………………………………………………………… 10 Group Workshop on guidelines for Northern bald Ibis release ………………… 12 Mike Jordan, Christiane Boehm & -

SIS Conservation Publication of the IUCN SSC Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Specialist Group

SIS Conservation Publication of the IUCN SSC Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Specialist Group ISSUE 1, 2019 SPECIAL ISSUE: GLOSSY IBIS ECOLOGY & CONSERVATION Editors-in-chief: K.S. Gopi Sundar and Luis Santiago Cano Alonso Guest Editor for Special Issue: Simone Santoro ISBN 978-2-491451-01-1 SIS Conservation Piotr Tryjanowski, Poland Publication of the IUCN SSC Stork, Ibis & Spoonbill Abdul J. Urfi, India Specialist Group Amanda Webber, United Kingdom View this journal online at https://storkibisspoonbill.org/sis-conservation- SPECIAL ISSUE GUEST EDITOR publications/ Simone Santoro PhD | University Pablo Olavide | Spain AIMS AND SCOPE Special Issue Editorial Board Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Conservation (SISC) is a peer- Mauro Fasola PhD | Università di Pavia| Italy reviewed publication of the IUCN SSC Stork, Ibis and Ricardo Lima PhD | University of Lisbon | Portugal Spoonbill Specialist Group. SISC publishes original Jocelyn Champagnon PhD | Tour du Valat| France content on the ecology and conservation of both wild and Alejandro Centeno PhD | University of Cádiz | Spain captive populations of SIS species worldwide, with the Amanda Webber PhD | Bristol Zoological Society| UK aim of disseminating information to assist in the Frédéric Goes MSc | Osmose |France management and conservation of SIS (including Shoebill) André Stadler PhD | Alpenzoo Innsbruck |Austria populations and their habitats worldwide. We invite Letizia Campioni PhD | MARE, ISPA|Portugal anyone, including people who are not members of the Piotr Tryjanowski PhD | Poznań University of Life SIS-SG, to submit manuscripts. Sciences| Poland The views expressed in this publication are those of the Phillippe Dubois MSc | Independent Researcher | France authors and do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN, nor Catherine King MSc | Zoo Lagos |Portugal the IUCN SSC Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Specialist Group. -

Northern Bald Ibis the Most Threatened Bird of the Middle East

Northern Bald Ibis The Most Threatened Bird of the Middle East THE LAST FLIGHT OF THE ANCIENT GUIDE OF HAJJ 2002 - 2011 NINE YEARS OF CONSERVATION EFFORTS BETWEEN ARABIA AND EAST AFRICA Northern Bald Ibis The Most Threatened Bird Each species is a small universe in its own, different from all the others due to its genes, of the Middle East anatomy, behaviour, vital cycle, role in the ecosystem; a self-sustaining system, created in the course of an evolutionary history, complex beyond our imagination. Each species deserves that researchers devote their careers on it, and poets and historians celebrate it. Nothing even closely similar can be said about a proton or an hydrogen atom. In few words, Reverend, this is the strongest and most transcendent moral argument, provided by science in view of supporting the urgent need to save the Creation. E.O. WILSON (The Creation, 2006) THE LAST FLIGHT OF THE ANCIENT GUIDE OF HAJJ 2002 - 2011 NINE YEARS OF CONSERVATION EFFORTS BETWEEN ARABIA AND EAST AFRICA Committee for Research Syrian General Commission and Exploration for Badia Management and Development Saudi Wildlife Authority CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This publication was made possible by a grant from the Mohamed Bin Zayed SUMMARY PAG 7 Foundation. Cooperation and support from the Syrian Desert Commission, the Ethiopian Wildlife Society and the Saudi Wildlife Authority were instrumental to 1. BACKGROUND PAG 11 run this long-term conservation project. It was made possible by multi-year funds made available by the Italian Development Cooperation (DGCS) and by several grants from RSPB, Embassies of Finland and Netherlands in Damascus, Monaco 2. -

Fall 2017 3 Maricopa Audubon Society Field Trips

The Cactus WrenNotes &• Announcementsdition Volume LXV, No. 3 Fall - 2017 Painted Lady Photo by Marceline VandeWater Programs people with nature through birds. She is an Meetings are held in Scottsdale: avid climber and backpacker. Cathy graduated Papago Buttes Church of the Brethren from the University of California, Davis with a (northwest of 64th Street and Oak Street, BS in Avian Sciences. which is between Thomas Road and McDowell Road). You may enter from 64th November 7, 2017 Street, just north of Oak Street. If coming from Erik Andersen the south, turn left (west) at Oak Street and Effects of Plant Invasions on then right at the Elks Lodge. Continue north Grassland Birds programs along the eastern edge of their parking lot For the past few years, Erik Andersen has and turn right into the church parking lot. Look studied how shrub encroachment and for signs that say “Audubon.” Come and join nonnative grasses affect density, nest us and bring a friend! MAS holds a monthly Wendsler Nosie, Sr. meeting on the first Tuesday of the month from National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). events & programs September through April. Hear about the Apache Stronghold trip to our nation’s capitol, the resistance at Oak Flat, and the fight to protect the land and water for September 5, 2017 future generations from two foreign mining companies. Wendsler Nosie, Sr. From Oak Flat to DC October 2, 2017 On July 5, 2015 Wendsler Nosie, Sr. took the San Carlos Apache Stronghold on a caravan Cathy Wise from Tucson to Washington, DC to request the Plants for Birds federal government support a bill introduced This fall planting season, don’t forget your by Arizona congressman Raul Grijalva to save feathered friends! Attract more native birds Erik Andersen Oak Flat. -

Contribution of Research to Conservation Action for the Northern Bald Ibis Geronticus Eremita in Morocco

Bird Conservation International (2008) 18:S74–S90. ß BirdLife International 2008 doi:10.1017/S0959270908000403 Printed in the United Kingdom Contribution of research to conservation action for the Northern Bald Ibis Geronticus eremita in Morocco CHRISTOPHER G. R. BOWDEN, KEN W. SMITH, MOHAMMED EL BEKKAY, WIDADE OUBROU, ALI AGHNAJ and MARIA JIMENEZ-ARMESTO Summary The Northern Bald Ibis or Waldrapp Geronticus eremita is a species of arid semi-deserts and steppes, which was formerly widely distributed as a breeding bird across North Africa, the Middle East and the European Alps. Just over 100 breeding pairs now remain in the wild at two sites in Morocco whilst two further wild pairs remain in Syria. There is also a population in Turkey, which is maintained for part of the year in captivity, and a large captive population in zoos. The species is classified by IUCN as ‘Critically Endangered’, the highest threat category. The wild population has grown during the past decade, which represents the first evidence of population growth in the species’ recorded history. Conservation action in Morocco has contributed to this recovery. A large part of the contribution of research to conservation action has been to establish and document the value of simple site and species protection. Quantitative assessments of the importance of sites for breeding, roosting and foraging have helped to prevent disturbance and the loss of sites to mass-tourism development. Wardening by members of the local community have reduced disturbance by local people and others and increased the perceived value of the birds. Monitoring has suggested additional ways to improve the breeding status of the species, including the provision of drinking water and removal and deterrence of predators and competitors. -

First Record of the Northern Bald Ibis Geronticus Eremita (Linnaeus, 1758) in Bulgaria

Historia naturalis bulgarica 41: 23–26 ISSN 0205-3640 (print) | ISSN 2603-3186 (online) • nmnhs.com/historia-naturalis-bulgarica https://doi.org/10.48027/hnb.41.03001 Publication date [online]: 6 January 2020 Research article First record of the northern bald ibis Geronticus eremita (Linnaeus, 1758) in Bulgaria Zlatozar Boev1, Gradimir Gradev2, Hristina Klisurova3, Ivaylo Klisurov4, Rusko Petrov5 1 National Museum of Natural History, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, 1 Tsar Osvoboditel Blvd, 1000 Sofia, Bulgaria, [email protected], [email protected] 2 Wildlife Rehabilitation and Breeding Center, Green Balkans – Stara Zagora, 9 Stara Planina Street, Stara Zagora 6000, Bulgaria, [email protected] 3 Wildlife Rehabilitation and Breeding Center, Green Balkans – Stara Zagora, 9 Stara Planina Street, Stara Zagora 6000, Bulgaria, [email protected] 4 Wildlife Rehabilitation and Breeding Center, Green Balkans – Stara Zagora, 9 Stara Planina Street, Stara Zagora 6000, Bulgaria, [email protected] 5 Wildlife Rehabilitation and Breeding Center, Green Balkans – Stara Zagora, 9 Stara Planina Street, Stara Zagora 6000, Bulgaria, [email protected] Abstract: The paper reports on the first record of Geronticus eremita in Bulgaria (13–16 January 2019; town of Karlovo), a specimen released from the captive population in Rosegg Tierpark, Austria and caught alive in the town of Karlovo (CS Bulgaria). Regardless of the attempts to be rescued a few days later, it died. Keywords: avian rarities, Balkan avifauna, birds of Bulgaria, bird reintroduction, endangered birds Introduction (del Hoyo & Collar, 2014) and the native nominate race Ph. c. colchicus Linnaeus, 1758 of the common At present, the northern bald ibis, Geronticus eremita pheasant, disappeared ca. -

Northern Bald Ibis Geronticus Eremita Behaviour

Northern Bald Ibis Geronticus eremita behaviour CHRISTIANE BÖHM Northern Bald Ibis species co-ordinator Alpenzoo Innsbruck-Tirol [email protected] The NBI is an ideal zoo bird: it is big, socially active and the public is attracted by this gregarious and somehow “ugly” or better special bird species. The NBI shows a distinctive behaviour which is easy to observe. In the Alpenzoo Innsbruck-Tirol a lot of behavioural studies of the NBI have been done (e.g. ETTL 1979, PEGORARO 1983, 1992, 1996, THALER & JOB 1981) and the ethogram of the NBI could be made out. A behavioural guide has been published in the 2nd Northern Bald Ibis studbook in 1999. This lightly revised version is thought as a tool for daily work with the NBI for bird keepers, as a basis for public information or pupils who have to do behavioural exercises. 1. Daily activity pattern in captivity In captivity Northern Bald Ibises start their daily activity late compared to other species. On cold days NBI may start leaving their sleeping sites later than 9 a.m. First day activities normally comprise comfort behaviour (yawning, preening) and greetings to their partners and the other colony members. Thereafter the birds enter the ground and start foraging and feeding. The most active hours are the late morning (between 10-12 a.m.) and during the late afternoon (15-17 p.m.). During midday most of the specimens within a given colony are roosting and inactive for 1-2 hours. Cold temperatures (<10 oC), rain and snowfall generally reduce the activity.