Reading and Researching Photographs Helena Zinkham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statement by the Association of Hoving Image Archivists (AXIA) To

Statement by the Association of Hoving Image Archivists (AXIA) to the National FTeservation Board, in reference to the Uational Pilm Preservation Act of 1992, submitted by Dr. Jan-Christopher Eorak , h-esident The Association of Moving Image Archivists was founded in November 1991 in New York by representatives of over eighty American and Canadian film and television archives. Previously grouped loosely together in an ad hoc organization, Pilm Archives Advisory Committee/Television Archives Advisory Committee (FAAC/TAAC), it was felt that the field had matured sufficiently to create a national organization to pursue the interests of its constituents. According to the recently drafted by-laws of the Association, AHIA is a non-profit corporation, chartered under the laws of California, to provide a means for cooperation among individuals concerned with the collection, preservation, exhibition and use of moving image materials, whether chemical or electronic. The objectives of the Association are: a.) To provide a regular means of exchanging information, ideas, and assistance in moving image preservation. b.) To take responsible positions on archival matters affecting moving images. c.) To encourage public awareness of and interest in the preservation, and use of film and video as an important educational, historical, and cultural resource. d.) To promote moving image archival activities, especially preservation, through such means as meetings, workshops, publications, and direct assistance. e. To promote professional standards and practices for moving image archival materials. f. To stimulate and facilitate research on archival matters affecting moving images. Given these objectives, the Association applauds the efforts of the National Film Preservation Board, Library of Congress, to hold public hearings on the current state of film prese~ationin 2 the United States, as a necessary step in implementing the National Film Preservation Act of 1992. -

The Positive and Negative Effects of Photography on Wildlife

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University Undergraduate Honors Theses Honors Program 2020 The Positive and Negative Effects of Photography on Wildlife Joy Smith Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/undergrad-honors Part of the Photography Commons The Positive and Negative Effects of Photography on Wildlife An Honors Thesis Presented to The University Honors Program Gardner-Webb University 10 April 2020 by Joy Smith Accepted by the Honors Faculty _______________________________ ________________________________________ Dr. Robert Carey, Thesis Advisor Dr. Tom Jones, Associate Dean, Univ. Honors _______________________________ _______________________________________ Prof. Frank Newton, Honors Committee Dr. Christopher Nelson, Honors Committee _______________________________ _______________________________________ Dr. Bob Bass, Honors Committee Dr. Shea Stuart, Honors Committee I. Overview of Wildlife Photography The purpose of this thesis is to research the positive and negative effects photography has on animals. This includes how photographers have helped to raise awareness about endangered species, as well as how people have hurt animals by getting them too used to cameras and encroaching on their space to take photos. Photographers themselves have been a tremendous help towards the fight to protect animals. Many of them have made it their life's mission to capture photos of elusive animals who are on the verge of extinction. These people know how to properly interact with an animal; they leave them alone and stay as hidden as possible while photographing them so as to not cause the animals any distress. However, tourists, amateur photographers, and a small number of professional photographers can be extremely harmful to animals. When photographing animals, their habitats can become disturbed, they can become very frightened and put in harm's way, and can even hurt or kill photographers who make them feel threatened. -

Inclusion in the Recording Studio? Gender and Race/Ethnicity of Artists, Songwriters & Producers Across 900 Popular Songs from 2012-2020

Inclusion in the Recording Studio? Gender and Race/Ethnicity of Artists, Songwriters & Producers across 900 Popular Songs from 2012-2020 Dr. Stacy L. Smith, Dr. Katherine Pieper, Marc Choueiti, Karla Hernandez & Kevin Yao March 2021 INCLUSION IN THE RECORDING STUDIO? EXAMINING POPULAR SONGS USC ANNENBERG INCLUSION INITIATIVE @Inclusionists WOMEN ARE MISSING IN POPULAR MUSIC Prevalence of Women Artists across 900 Songs, in percentages 28.1 TOTAL NUMBER 25.1 OF ARTISTS 1,797 22.7 21.9 22.5 20.9 20.2 RATIO OF MEN TO WOMEN 16.8 17.1 3.6:1 ‘12 ‘13 ‘14 ‘15 ‘16 ‘17 ‘18 ‘19 ‘20 FOR WOMEN, MUSIC IS A SOLO ACTIVITY Across 900 songs, percentage of women out of... 21.6 30 7.1 7.3 ALL INDIVIDUAL DUOS BANDS ARTISTS ARTISTS (n=388) (n=340) (n=9) (n=39) WOMEN ARE PUSHED ASIDE AS PRODUCERS THE RATIO OF MEN TO WOMEN PRODUCERS ACROSS 600 POPULAR SONGS WAS 38 to 1 © DR. STACY L. SMITH WRITTEN OFF: FEW WOMEN WORK AS SONGWRITERS Songwriter gender by year... 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 TOTAL 11% 11.7% 12.7% 13.7% 13.3% 11.5% 11.6% 14.4% 12.9% 12.6% 89% 88.3% 87.3% 86.3% 86.7% 88.5% 88.4% 85.6% 87.1% 87.4% WOMEN ARE MISSING IN THE MUSIC INDUSTRY Percentage of women across three creative roles... .% .% .% ARE ARE ARE ARTISTS SONGWRITERS PRODUCERS VOICES HEARD: ARTISTS OF COLOR ACROSS SONGS Percentage of artists of color by year... 59% 55.6% 56.1% 51.9% 48.7% 48.4% 38.4% 36% 46.7% 31.2% OF ARTISTS WERE PEOPLE OF COLOR ACROSS SONGS FROM ‘12 ‘13 ‘14 ‘15 ‘16 ‘17 ‘18 ‘19 ‘20 © DR. -

Session Outline: History of the Daguerreotype

Fundamentals of the Conservation of Photographs SESSION: History of the Daguerreotype INSTRUCTOR: Grant B. Romer SESSION OUTLINE ABSTRACT The daguerreotype process evolved out of the collaboration of Louis Jacques Mande Daguerre (1787- 1851) and Nicephore Niepce, which began in 1827. During their experiments to invent a commercially viable system of photography a number of photographic processes were evolved which contributed elements that led to the daguerreotype. Following Niepce’s death in 1833, Daguerre continued experimentation and discovered in 1835 the basic principle of the process. Later, investigation of the process by prominent scientists led to important understandings and improvements. By 1843 the process had reached technical perfection and remained the commercially dominant system of photography in the world until the mid-1850’s. The image quality of the fine daguerreotype set the photographic standard and the photographic industry was established around it. The standardized daguerreotype process after 1843 entailed seven essential steps: plate polishing, sensitization, camera exposure, development, fixation, gilding, and drying. The daguerreotype process is explored more fully in the Technical Note: Daguerreotype. The daguerreotype image is seen as a positive to full effect through a combination of the reflection the plate surface and the scattering of light by the imaging particles. Housings exist in great variety of style, usually following the fashion of miniature portrait presentation. The daguerreotype plate is extremely vulnerable to mechanical damage and the deteriorating influences of atmospheric pollutants. Hence, highly colored and obscuring corrosion films are commonly found on daguerreotypes. Many daguerreotypes have been damaged or destroyed by uninformed attempts to wipe these films away. -

Digital Camera Functions All Photography Is Based on the Same

Digital Camera Functions All photography is based on the same optical principle of viewing objects with our eyes. In both cases, light is reflected off of an object and passes through a lens, which focuses the light rays, onto the light sensitive retina, in the case of eyesight, or onto film or an image sensor the case of traditional or digital photography. The shutter is a curtain that is placed between the lens and the camera that briefly opens to let light hit the film in conventional photography or the image sensor in digital photography. The shutter speed refers to how long the curtain stays open to let light in. The higher the number, the shorter the time, and consequently, the less light gets in. So, a shutter speed of 1/60th of a second lets in half the amount of light than a speed of 1/30th of a second. For most normal pictures, shutter speeds range from 1/30th of a second to 1/100th of a second. A faster shutter speed, such as 1/500th of a second or 1/1000th of a second, would be used to take a picture of a fast moving object such as a race car; while a slow shutter speed would be used to take pictures in low-light situations, such as when taking pictures of the moon at night. Remember that the longer the shutter stays open, the more chance the image will be blurred because a person cannot usually hold a camera still for very long. A tripod or other support mechanism should almost always be used to stabilize the camera when slow shutter speeds are used. -

Ava Max Could Always Envision Her Dream, She Actually Went out and Made It a Reality on Her Own

For dreams to manifest into reality, it requires more than a fairytale wish… Truthfully, it takes hustle, heart, and a whole lot of attitude. For as much as Ava Max could always envision her dream, she actually went out and made it a reality on her own. Gathering billions of streams, multiplatinum plaques, award nominations, and acclaim from The New York Times, Rolling Stone, and many more, the international phenomenon projects an unbelievable personal journey into a poignant and punchy pop opus on her full-length debut album, Heaven & Hell [APG/Atlantic Records]. “Manifesting is really important to me,” she explains. “I put positive energy into my music. I know what I want to write, and there’s a story behind each song. It’s all about working hard and putting your heart and soul into it.” She started doing so as a kid. Prior to her birth in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Ava’s parents emigrated from Albania to the United States. Without speaking a word of English, mom and dad held down three jobs each. However, both parents retained a passion for music. Among her earliest memories, Ava recalls her mother—a classically trained vocalist—singing opera aloud. The family relocated to Virginia where they eventually settled in their first house. Along the way, Ava clung to music, listening to Whitney Houston, Mariah Carey, and Shania Twain, to name a few. “At a very young age, I watched my parents really struggle in America,” she admits. “It was tough, and it impacted me in many ways. However, both of them always told me if they could make it here with no language and no money, then I could make it.” While in Virginia, she dove headfirst into music with the family staunchly behind her. -

Lab 11: the Compound Microscope

OPTI 202L - Geometrical and Instrumental Optics Lab 9-1 LAB 9: THE COMPOUND MICROSCOPE The microscope is a widely used optical instrument. In its simplest form, it consists of two lenses Fig. 9.1. An objective forms a real inverted image of an object, which is a finite distance in front of the lens. This image in turn becomes the object for the ocular, or eyepiece. The eyepiece forms the final image which is virtual, and magnified. The overall magnification is the product of the individual magnifications of the objective and the eyepiece. Figure 9.1. Images in a compound microscope. To illustrate the concept, use a 38 mm focal length lens (KPX079) as the objective, and a 50 mm focal length lens (KBX052) as the eyepiece. Set them up on the optical rail and adjust them until you see an inverted and magnified image of an illuminated object. Note the intermediate real image by inserting a piece of paper between the lenses. Q1 ● Can you demonstrate the final image by holding a piece of paper behind the eyepiece? Why or why not? The eyepiece functions as a magnifying glass, or simple magnifier. In effect, your eye looks into the eyepiece, and in turn the eyepiece looks into the optical system--be it a compound microscope, a spotting scope, telescope, or binocular. In all cases, the eyepiece doesn't view an actual object, but rather some intermediate image formed by the "front" part of the optical system. With telescopes, this intermediate image may be real or virtual. With the compound microscope, this intermediate image is real, formed by the objective lens. -

Image Compression Using Discrete Cosine Transform Method

Qusay Kanaan Kadhim, International Journal of Computer Science and Mobile Computing, Vol.5 Issue.9, September- 2016, pg. 186-192 Available Online at www.ijcsmc.com International Journal of Computer Science and Mobile Computing A Monthly Journal of Computer Science and Information Technology ISSN 2320–088X IMPACT FACTOR: 5.258 IJCSMC, Vol. 5, Issue. 9, September 2016, pg.186 – 192 Image Compression Using Discrete Cosine Transform Method Qusay Kanaan Kadhim Al-Yarmook University College / Computer Science Department, Iraq [email protected] ABSTRACT: The processing of digital images took a wide importance in the knowledge field in the last decades ago due to the rapid development in the communication techniques and the need to find and develop methods assist in enhancing and exploiting the image information. The field of digital images compression becomes an important field of digital images processing fields due to the need to exploit the available storage space as much as possible and reduce the time required to transmit the image. Baseline JPEG Standard technique is used in compression of images with 8-bit color depth. Basically, this scheme consists of seven operations which are the sampling, the partitioning, the transform, the quantization, the entropy coding and Huffman coding. First, the sampling process is used to reduce the size of the image and the number bits required to represent it. Next, the partitioning process is applied to the image to get (8×8) image block. Then, the discrete cosine transform is used to transform the image block data from spatial domain to frequency domain to make the data easy to process. -

Cyanotype Detailed Instructions

Cyanotype Detailed Instructions Cyanotype Formula, Mixing and Exposing Instructions 1. Dissolve 40 g (approximately 2 tablespoons) Potassium Ferricyanide in 400 ml (1.7 cups) water to create STOCK SOLUTION A. Allow 24 hours for the powder to fully dissolve. 2. Dissolve 100 g (approximately .5 cup) Ferric Ammonium Citrate in 400 ml (1.7 cups) water to create if you have Chemistry Open Stock START HERE STOCK SOLUTION B. Allow 24 hours for the powder to fully dissolve. If using the Cyanotype Sensitizer Set, simply fill each bottle with water, shake and allow 24 hours for the powders to dissolve. 3. In subdued lighting, mix equal parts SOLUTION A and SOLUTION B to create the cyanotype sensitizer. Mix only the amount you immediately need, as the sensitizer is stable just 2-4 hours. if you have the Sensitizer Set START HERE 4. Coat paper or fabric with the sensitizer and allow to air dry in the dark. Paper may be double-coated for denser prints. Fabric may be coated or dipped in the sensitizer. Jacquard’s Cyanotype Fabric Sheets and Mural Fabrics are pre-treated with the sensitizer (as above) and come ready to expose. 5. Make exposures in sunlight (1-30 minutes, depending on conditions) or under a UV light source, placing ob- jects or a film negative on the coated surface to create an image. (Note: Over-exposure is almost always preferred to under-exposure.) The fabric will look bronze in color once fully exposed. 6. Process prints in a tray or bucket of cool water. Wash for at least 5 minutes, changing the water periodically, if you have until the water runs clear. -

Ground-Based Photographic Monitoring

United States Department of Agriculture Ground-Based Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station Photographic General Technical Report PNW-GTR-503 Monitoring May 2001 Frederick C. Hall Author Frederick C. Hall is senior plant ecologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Region, Natural Resources, P.O. Box 3623, Portland, Oregon 97208-3623. Paper prepared in cooperation with the Pacific Northwest Region. Abstract Hall, Frederick C. 2001 Ground-based photographic monitoring. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-503. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 340 p. Land management professionals (foresters, wildlife biologists, range managers, and land managers such as ranchers and forest land owners) often have need to evaluate their management activities. Photographic monitoring is a fast, simple, and effective way to determine if changes made to an area have been successful. Ground-based photo monitoring means using photographs taken at a specific site to monitor conditions or change. It may be divided into two systems: (1) comparison photos, whereby a photograph is used to compare a known condition with field conditions to estimate some parameter of the field condition; and (2) repeat photo- graphs, whereby several pictures are taken of the same tract of ground over time to detect change. Comparison systems deal with fuel loading, herbage utilization, and public reaction to scenery. Repeat photography is discussed in relation to land- scape, remote, and site-specific systems. Critical attributes of repeat photography are (1) maps to find the sampling location and of the photo monitoring layout; (2) documentation of the monitoring system to include purpose, camera and film, w e a t h e r, season, sampling technique, and equipment; and (3) precise replication of photographs. -

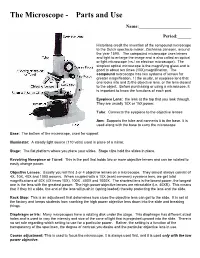

The Microscope Parts And

The Microscope Parts and Use Name:_______________________ Period:______ Historians credit the invention of the compound microscope to the Dutch spectacle maker, Zacharias Janssen, around the year 1590. The compound microscope uses lenses and light to enlarge the image and is also called an optical or light microscope (vs./ an electron microscope). The simplest optical microscope is the magnifying glass and is good to about ten times (10X) magnification. The compound microscope has two systems of lenses for greater magnification, 1) the ocular, or eyepiece lens that one looks into and 2) the objective lens, or the lens closest to the object. Before purchasing or using a microscope, it is important to know the functions of each part. Eyepiece Lens: the lens at the top that you look through. They are usually 10X or 15X power. Tube: Connects the eyepiece to the objective lenses Arm: Supports the tube and connects it to the base. It is used along with the base to carry the microscope Base: The bottom of the microscope, used for support Illuminator: A steady light source (110 volts) used in place of a mirror. Stage: The flat platform where you place your slides. Stage clips hold the slides in place. Revolving Nosepiece or Turret: This is the part that holds two or more objective lenses and can be rotated to easily change power. Objective Lenses: Usually you will find 3 or 4 objective lenses on a microscope. They almost always consist of 4X, 10X, 40X and 100X powers. When coupled with a 10X (most common) eyepiece lens, we get total magnifications of 40X (4X times 10X), 100X , 400X and 1000X. -

Photographic Films

PHOTOGRAPHIC FILMS A camera has been called a “magic box.” Why? Because the box captures an image that can be made permanent. Photographic films capture the image formed by light reflecting from the surface being photographed. This instruction sheet describes the nature of photographic films, especially those used in the graphic communications industries. THE STRUCTURE OF FILM Protective Coating Emulsion Base Anti-Halation Backing Photographic films are composed of several layers. These layers include the base, the emulsion, the anti-halation backing and the protective coating. THE BASE The base, the thickest of the layers, supports the other layers. Originally, the base was made of glass. However, today the base can be made from any number of materials ranging from paper to aluminum. Photographers primarily use films with either a plastic (polyester) or paper base. Plastic-based films are commonly called “films” while paper-based films are called “photographic papers.” Polyester is a particularly suitable base for film because it is dimensionally stable. Dimensionally stable materials do not appreciably change size when the temperature or moisture- level of the film change. Films are subjected to heated liquids during processing (developing) and to heat during use in graphic processes. Therefore, dimensional stability is very important for graphic communications photographers because their final images must always match the given size. Conversely, paper is not dimen- sionally stable and is only appropriate as a film base when the “photographic print” is the final product (as contrasted to an intermediate step in a multi-step process). THE EMULSION The emulsion is the true “heart” of film.