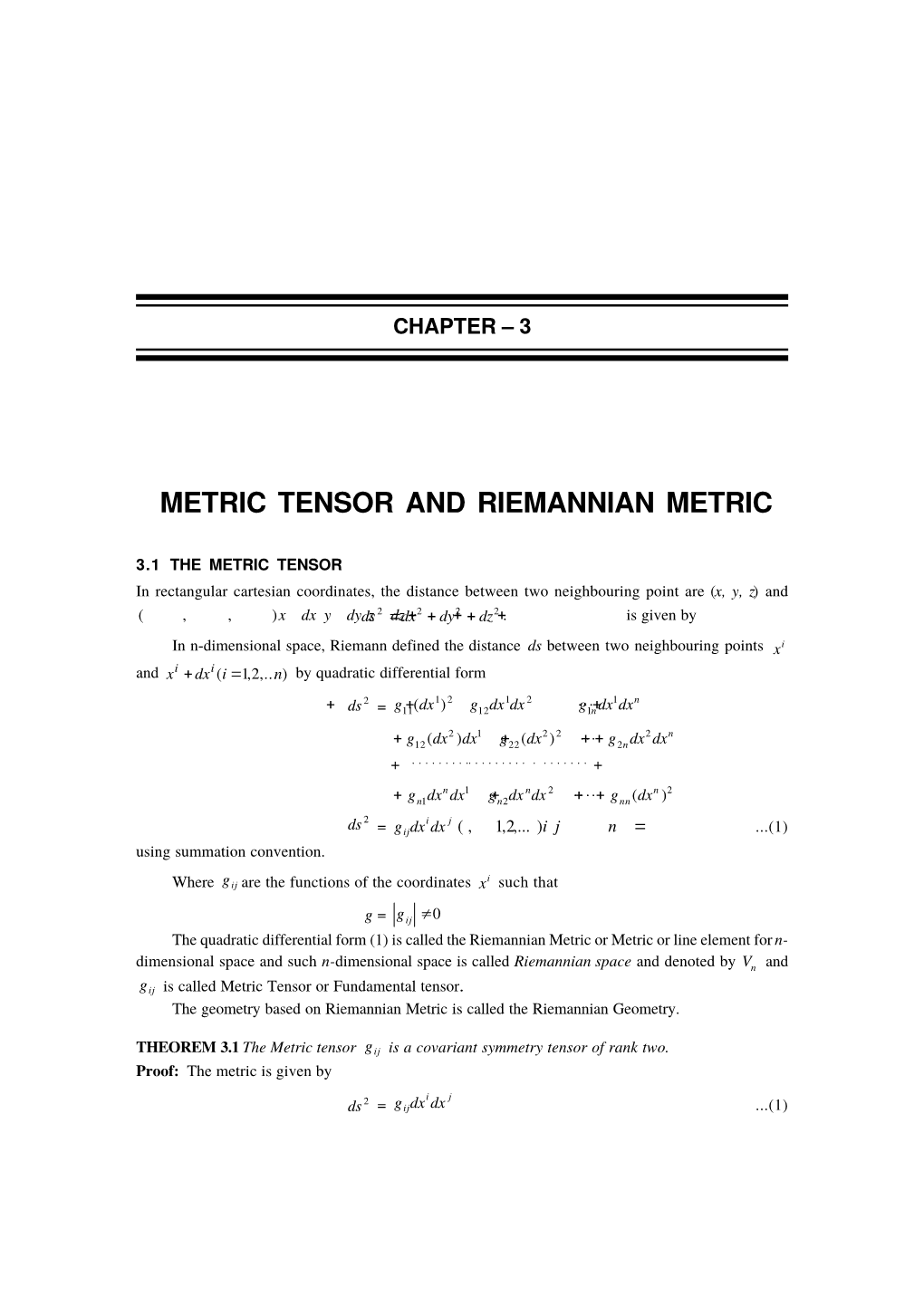

Metric Tensor and Riemannian Metric

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Relativity Fall 2018 Lecture 10: Integration, Einstein-Hilbert Action

General Relativity Fall 2018 Lecture 10: Integration, Einstein-Hilbert action Yacine Ali-Ha¨ımoud (Dated: October 3, 2018) σ σ HW comment: T µν antisym in µν does NOT imply that Tµν is antisym in µν. Volume element { Consider a LICS with primed coordinates. The 4-volume element is dV = d4x0 = 0 0 0 0 dx0 dx1 dx2 dx3 . If we change coordinates, we have 0 ! @xµ d4x0 = det d4x: (1) µ @x Now, the metric components change as 0 0 0 0 @xµ @xν @xµ @xν g = g 0 0 = η 0 0 ; (2) µν @xµ @xν µ ν @xµ @xν µ ν since the metric components are ηµ0ν0 in the LICS. Seing this as a matrix operation and taking the determinant, we find 0 !2 @xµ det(g ) = − det : (3) µν @xµ Hence, we find that the 4-volume element is q 4 p 4 p 4 dV = − det(gµν )d x ≡ −g d x ≡ jgj d x: (4) The integral of a scalar function f is well defined: given any coordinate system (even if only defined locally): Z Z f dV = f pjgj d4x: (5) We can only define the integral of a scalar function. The integral of a vector or tensor field is mean- ingless in curved spacetime. Think of the integral as a sum. To sum vectors, you need them to belong to the same vector space. There is no common vector space in curved spacetime. Only in flat spacetime can we define such integrals. First parallel-transport the vector field to a single point of spacetime (it doesn't matter which one). -

Topology and Physics 2019 - Lecture 2

Topology and Physics 2019 - lecture 2 Marcel Vonk February 12, 2019 2.1 Maxwell theory in differential form notation Maxwell's theory of electrodynamics is a great example of the usefulness of differential forms. A nice reference on this topic, though somewhat outdated when it comes to notation, is [1]. For notational simplicity, we will work in units where the speed of light, the vacuum permittivity and the vacuum permeability are all equal to 1: c = 0 = µ0 = 1. 2.1.1 The dual field strength In three dimensional space, Maxwell's electrodynamics describes the physics of the electric and magnetic fields E~ and B~ . These are three-dimensional vector fields, but the beauty of the theory becomes much more obvious if we (a) use a four-dimensional relativistic formulation, and (b) write it in terms of differential forms. For example, let us look at Maxwells two source-free, homogeneous equations: r · B = 0;@tB + r × E = 0: (2.1) That these equations have a relativistic flavor becomes clear if we write them out in com- ponents and organize the terms somewhat suggestively: x y z 0 + @xB + @yB + @zB = 0 x z y −@tB + 0 − @yE + @zE = 0 (2.2) y z x −@tB + @xE + 0 − @zE = 0 z y x −@tB − @xE + @yE + 0 = 0 Note that we also multiplied the last three equations by −1 to clarify the structure. All in all, we see that we have four equations (one for each space-time coordinate) which each contain terms in which the four coordinate derivatives act. Therefore, we may be tempted to write our set of equations in more \relativistic" notation as ^µν @µF = 0 (2.3) 1 with F^µν the coordinates of an antisymmetric two-tensor (i. -

LP THEORY of DIFFERENTIAL FORMS on MANIFOLDS This

TRANSACTIONSOF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICALSOCIETY Volume 347, Number 6, June 1995 LP THEORY OF DIFFERENTIAL FORMS ON MANIFOLDS CHAD SCOTT Abstract. In this paper, we establish a Hodge-type decomposition for the LP space of differential forms on closed (i.e., compact, oriented, smooth) Rieman- nian manifolds. Critical to the proof of this result is establishing an LP es- timate which contains, as a special case, the L2 result referred to by Morrey as Gaffney's inequality. This inequality helps us show the equivalence of the usual definition of Sobolev space with a more geometric formulation which we provide in the case of differential forms on manifolds. We also prove the LP boundedness of Green's operator which we use in developing the LP theory of the Hodge decomposition. For the calculus of variations, we rigorously verify that the spaces of exact and coexact forms are closed in the LP norm. For nonlinear analysis, we demonstrate the existence and uniqueness of a solution to the /1-harmonic equation. 1. Introduction This paper contributes primarily to the development of the LP theory of dif- ferential forms on manifolds. The reader should be aware that for the duration of this paper, manifold will refer only to those which are Riemannian, compact, oriented, C°° smooth and without boundary. For p = 2, the LP theory is well understood and the L2-Hodge decomposition can be found in [M]. However, in the case p ^ 2, the LP theory has yet to be fully developed. Recent appli- cations of the LP theory of differential forms on W to both quasiconformal mappings and nonlinear elasticity continue to motivate interest in this subject. -

NOTES on DIFFERENTIAL FORMS. PART 3: TENSORS 1. What Is A

NOTES ON DIFFERENTIAL FORMS. PART 3: TENSORS 1. What is a tensor? 1 n Let V be a finite-dimensional vector space. It could be R , it could be the tangent space to a manifold at a point, or it could just be an abstract vector space. A k-tensor is a map T : V × · · · × V ! R 2 (where there are k factors of V ) that is linear in each factor. That is, for fixed ~v2; : : : ;~vk, T (~v1;~v2; : : : ;~vk−1;~vk) is a linear function of ~v1, and for fixed ~v1;~v3; : : : ;~vk, T (~v1; : : : ;~vk) is a k ∗ linear function of ~v2, and so on. The space of k-tensors on V is denoted T (V ). Examples: n • If V = R , then the inner product P (~v; ~w) = ~v · ~w is a 2-tensor. For fixed ~v it's linear in ~w, and for fixed ~w it's linear in ~v. n • If V = R , D(~v1; : : : ;~vn) = det ~v1 ··· ~vn is an n-tensor. n • If V = R , T hree(~v) = \the 3rd entry of ~v" is a 1-tensor. • A 0-tensor is just a number. It requires no inputs at all to generate an output. Note that the definition of tensor says nothing about how things behave when you rotate vectors or permute their order. The inner product P stays the same when you swap the two vectors, but the determinant D changes sign when you swap two vectors. Both are tensors. For a 1-tensor like T hree, permuting the order of entries doesn't even make sense! ~ ~ Let fb1;:::; bng be a basis for V . -

Killing Spinor-Valued Forms and the Cone Construction

ARCHIVUM MATHEMATICUM (BRNO) Tomus 52 (2016), 341–355 KILLING SPINOR-VALUED FORMS AND THE CONE CONSTRUCTION Petr Somberg and Petr Zima Abstract. On a pseudo-Riemannian manifold M we introduce a system of partial differential Killing type equations for spinor-valued differential forms, and study their basic properties. We discuss the relationship between solutions of Killing equations on M and parallel fields on the metric cone over M for spinor-valued forms. 1. Introduction The subject of the present article are the systems of over-determined partial differential equations for spinor-valued differential forms, classified as atypeof Killing equations. The solution spaces of these systems of PDE’s are termed Killing spinor-valued differential forms. A central question in geometry asks for pseudo-Riemannian manifolds admitting non-trivial solutions of Killing type equa- tions, namely how the properties of Killing spinor-valued forms relate to the underlying geometric structure for which they can occur. Killing spinor-valued forms are closely related to Killing spinors and Killing forms with Killing vectors as a special example. Killing spinors are both twistor spinors and eigenspinors for the Dirac operator, and real Killing spinors realize the limit case in the eigenvalue estimates for the Dirac operator on compact Riemannian spin manifolds of positive scalar curvature. There is a classification of complete simply connected Riemannian manifolds equipped with real Killing spinors, leading to the construction of manifolds with the exceptional holonomy groups G2 and Spin(7), see [8], [1]. Killing vector fields on a pseudo-Riemannian manifold are the infinitesimal generators of isometries, hence they influence its geometrical properties. -

Vector Calculus and Multiple Integrals Rob Fender, HT 2018

Vector Calculus and Multiple Integrals Rob Fender, HT 2018 COURSE SYNOPSIS, RECOMMENDED BOOKS Course syllabus (on which exams are based): Double integrals and their evaluation by repeated integration in Cartesian, plane polar and other specified coordinate systems. Jacobians. Line, surface and volume integrals, evaluation by change of variables (Cartesian, plane polar, spherical polar coordinates and cylindrical coordinates only unless the transformation to be used is specified). Integrals around closed curves and exact differentials. Scalar and vector fields. The operations of grad, div and curl and understanding and use of identities involving these. The statements of the theorems of Gauss and Stokes with simple applications. Conservative fields. Recommended Books: Mathematical Methods for Physics and Engineering (Riley, Hobson and Bence) This book is lazily referred to as “Riley” throughout these notes (sorry, Drs H and B) You will all have this book, and it covers all of the maths of this course. However it is rather terse at times and you will benefit from looking at one or both of these: Introduction to Electrodynamics (Griffiths) You will buy this next year if you haven’t already, and the chapter on vector calculus is very clear Div grad curl and all that (Schey) A nice discussion of the subject, although topics are ordered differently to most courses NB: the latest version of this book uses the opposite convention to polar coordinates to this course (and indeed most of physics), but older versions can often be found in libraries 1 Week One A review of vectors, rotation of coordinate systems, vector vs scalar fields, integrals in more than one variable, first steps in vector differentiation, the Frenet-Serret coordinate system Lecture 1 Vectors A vector has direction and magnitude and is written in these notes in bold e.g. -

Tensor Manipulation in GPL Maxima

Tensor Manipulation in GPL Maxima Viktor Toth http://www.vttoth.com/ February 1, 2008 Abstract GPL Maxima is an open-source computer algebra system based on DOE-MACSYMA. GPL Maxima included two tensor manipulation packages from DOE-MACSYMA, but these were in various states of disrepair. One of the two packages, CTENSOR, implemented component-based tensor manipulation; the other, ITENSOR, treated tensor symbols as opaque, manipulating them based on their index properties. The present paper describes the state in which these packages were found, the steps that were needed to make the packages fully functional again, and the new functionality that was implemented to make them more versatile. A third package, ATENSOR, was also implemented; fully compatible with the identically named package in the commercial version of MACSYMA, ATENSOR implements abstract tensor algebras. 1 Introduction GPL Maxima (GPL stands for the GNU Public License, the most widely used open source license construct) is the descendant of one of the world’s first comprehensive computer algebra systems (CAS), DOE-MACSYMA, developed by the United States Department of Energy in the 1960s and the 1970s. It is currently maintained by 18 volunteer developers, and can be obtained in source or object code form from http://maxima.sourceforge.net/. Like other computer algebra systems, Maxima has tensor manipulation capability. This capability was developed in the late 1970s. Documentation is scarce regarding these packages’ origins, but a select collection of e-mail messages by various authors survives, dating back to 1979-1982, when these packages were actively maintained at M.I.T. When this author first came across GPL Maxima, the tensor packages were effectively non-functional. -

Mathematical Theorems

Appendix A Mathematical Theorems The mathematical theorems needed in order to derive the governing model equations are defined in this appendix. A.1 Transport Theorem for a Single Phase Region The transport theorem is employed deriving the conservation equations in continuum mechanics. The mathematical statement is sometimes attributed to, or named in honor of, the German Mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibnitz (1646–1716) and the British fluid dynamics engineer Osborne Reynolds (1842–1912) due to their work and con- tributions related to the theorem. Hence it follows that the transport theorem, or alternate forms of the theorem, may be named the Leibnitz theorem in mathematics and Reynolds transport theorem in mechanics. In a customary interpretation the Reynolds transport theorem provides the link between the system and control volume representations, while the Leibnitz’s theorem is a three dimensional version of the integral rule for differentiation of an integral. There are several notations used for the transport theorem and there are numerous forms and corollaries. A.1.1 Leibnitz’s Rule The Leibnitz’s integral rule gives a formula for differentiation of an integral whose limits are functions of the differential variable [7, 8, 22, 23, 45, 55, 79, 94, 99]. The formula is also known as differentiation under the integral sign. H. A. Jakobsen, Chemical Reactor Modeling, DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-05092-8, 1361 © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2014 1362 Appendix A: Mathematical Theorems b(t) b(t) d ∂f (t, x) db da f (t, x) dx = dx + f (t, b) − f (t, a) (A.1) dt ∂t dt dt a(t) a(t) The first term on the RHS gives the change in the integral because the function itself is changing with time, the second term accounts for the gain in area as the upper limit is moved in the positive axis direction, and the third term accounts for the loss in area as the lower limit is moved. -

Line Element in Noncommutative Geometry

Line element in noncommutative geometry P. Martinetti G¨ottingenUniversit¨at Wroclaw, July 2009 . ? ? - & ? !? The line element p µ ν ds = gµν dx dx is mainly useful to measure distance Z y d(x; y) = inf ds: x If, for some quantum gravity reasons, [x µ; x ν ] 6= 0 is one losing the notion of distance ? (annoying then to speak of noncommutative geo-metry). ? - . ? !? The line element p µ ν ds = gµν dx dx & ? is mainly useful to measure distance Z y d(x; y) = inf ds: x If, for some quantum gravity reasons, [x µ; x ν ] 6= 0 is one losing the notion of distance ? (annoying then to speak of noncommutative geo-metry). ? - !? The line element p µ ν ds = gµν dx dx . & ? ? is mainly useful to measure distance Z y d(x; y) = inf ds: x If, for some quantum gravity reasons, [x µ; x ν ] 6= 0 is one losing the notion of distance ? (annoying then to speak of noncommutative geo-metry). ? - The line element p µ ν ds = gµν dx dx . & ? ? is mainly useful to measure distance Z y !? d(x; y) = inf ds: x If, for some quantum gravity reasons, [x µ; x ν ] 6= 0 is one losing the notion of distance ? (annoying then to speak of noncommutative geo-metry). The line element p µ ν ds = gµν dx dx . & ? ? is mainly useful to measure distance ? -Z y !? d(x; y) = inf ds: x If, for some quantum gravity reasons, [x µ; x ν ] 6= 0 is one losing the notion of distance ? (annoying then to speak of noncommutative geo-metry). -

SPINORS and SPACE–TIME ANISOTROPY

Sergiu Vacaru and Panayiotis Stavrinos SPINORS and SPACE{TIME ANISOTROPY University of Athens ————————————————— c Sergiu Vacaru and Panyiotis Stavrinos ii - i ABOUT THE BOOK This is the first monograph on the geometry of anisotropic spinor spaces and its applications in modern physics. The main subjects are the theory of grav- ity and matter fields in spaces provided with off–diagonal metrics and asso- ciated anholonomic frames and nonlinear connection structures, the algebra and geometry of distinguished anisotropic Clifford and spinor spaces, their extension to spaces of higher order anisotropy and the geometry of gravity and gauge theories with anisotropic spinor variables. The book summarizes the authors’ results and can be also considered as a pedagogical survey on the mentioned subjects. ii - iii ABOUT THE AUTHORS Sergiu Ion Vacaru was born in 1958 in the Republic of Moldova. He was educated at the Universities of the former URSS (in Tomsk, Moscow, Dubna and Kiev) and reveived his PhD in theoretical physics in 1994 at ”Al. I. Cuza” University, Ia¸si, Romania. He was employed as principal senior researcher, as- sociate and full professor and obtained a number of NATO/UNESCO grants and fellowships at various academic institutions in R. Moldova, Romania, Germany, United Kingdom, Italy, Portugal and USA. He has published in English two scientific monographs, a university text–book and more than hundred scientific works (in English, Russian and Romanian) on (super) gravity and string theories, extra–dimension and brane gravity, black hole physics and cosmolgy, exact solutions of Einstein equations, spinors and twistors, anistoropic stochastic and kinetic processes and thermodynamics in curved spaces, generalized Finsler (super) geometry and gauge gravity, quantum field and geometric methods in condensed matter physics. -

General Relativity Fall 2019 Lecture 11: the Riemann Tensor

General Relativity Fall 2019 Lecture 11: The Riemann tensor Yacine Ali-Ha¨ımoud October 8th 2019 The Riemann tensor quantifies the curvature of spacetime, as we will see in this lecture and the next. RIEMANN TENSOR: BASIC PROPERTIES α γ Definition { Given any vector field V , r[αrβ]V is a tensor field. Let us compute its components in some coordinate system: σ σ λ σ σ λ r[µrν]V = @[µ(rν]V ) − Γ[µν]rλV + Γλ[µrν]V σ σ λ σ λ λ ρ = @[µ(@ν]V + Γν]λV ) + Γλ[µ @ν]V + Γν]ρV 1 = @ Γσ + Γσ Γρ V λ ≡ Rσ V λ; (1) [µ ν]λ ρ[µ ν]λ 2 λµν where all partial derivatives of V µ cancel out after antisymmetrization. σ Since the left-hand side is a tensor field and V is a vector field, we conclude that R λµν is a tensor field as well { this is the tensor division theorem, which I encourage you to think about on your own. You can also check that explicitly from the transformation law of Christoffel symbols. This is the Riemann tensor, which measures the non-commutation of second derivatives of vector fields { remember that second derivatives of scalar fields do commute, by assumption. It is completely determined by the metric, and is linear in its second derivatives. Expression in LICS { In a LICS the Christoffel symbols vanish but not their derivatives. Let us compute the latter: 1 1 @ Γσ = @ gσδ (@ g + @ g − @ g ) = ησδ (@ @ g + @ @ g − @ @ g ) ; (2) µ νλ 2 µ ν λδ λ νδ δ νλ 2 µ ν λδ µ λ νδ µ δ νλ since the first derivatives of the metric components (thus of its inverse as well) vanish in a LICS. -

Math 865, Topics in Riemannian Geometry

Math 865, Topics in Riemannian Geometry Jeff A. Viaclovsky Fall 2007 Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 Lecture 1: September 4, 2007 4 2.1 Metrics, vectors, and one-forms . 4 2.2 The musical isomorphisms . 4 2.3 Inner product on tensor bundles . 5 2.4 Connections on vector bundles . 6 2.5 Covariant derivatives of tensor fields . 7 2.6 Gradient and Hessian . 9 3 Lecture 2: September 6, 2007 9 3.1 Curvature in vector bundles . 9 3.2 Curvature in the tangent bundle . 10 3.3 Sectional curvature, Ricci tensor, and scalar curvature . 13 4 Lecture 3: September 11, 2007 14 4.1 Differential Bianchi Identity . 14 4.2 Algebraic study of the curvature tensor . 15 5 Lecture 4: September 13, 2007 19 5.1 Orthogonal decomposition of the curvature tensor . 19 5.2 The curvature operator . 20 5.3 Curvature in dimension three . 21 6 Lecture 5: September 18, 2007 22 6.1 Covariant derivatives redux . 22 6.2 Commuting covariant derivatives . 24 6.3 Rough Laplacian and gradient . 25 7 Lecture 6: September 20, 2007 26 7.1 Commuting Laplacian and Hessian . 26 7.2 An application to PDE . 28 1 8 Lecture 7: Tuesday, September 25. 29 8.1 Integration and adjoints . 29 9 Lecture 8: September 23, 2007 34 9.1 Bochner and Weitzenb¨ock formulas . 34 10 Lecture 9: October 2, 2007 38 10.1 Manifolds with positive curvature operator . 38 11 Lecture 10: October 4, 2007 41 11.1 Killing vector fields . 41 11.2 Isometries . 44 12 Lecture 11: October 9, 2007 45 12.1 Linearization of Ricci tensor .