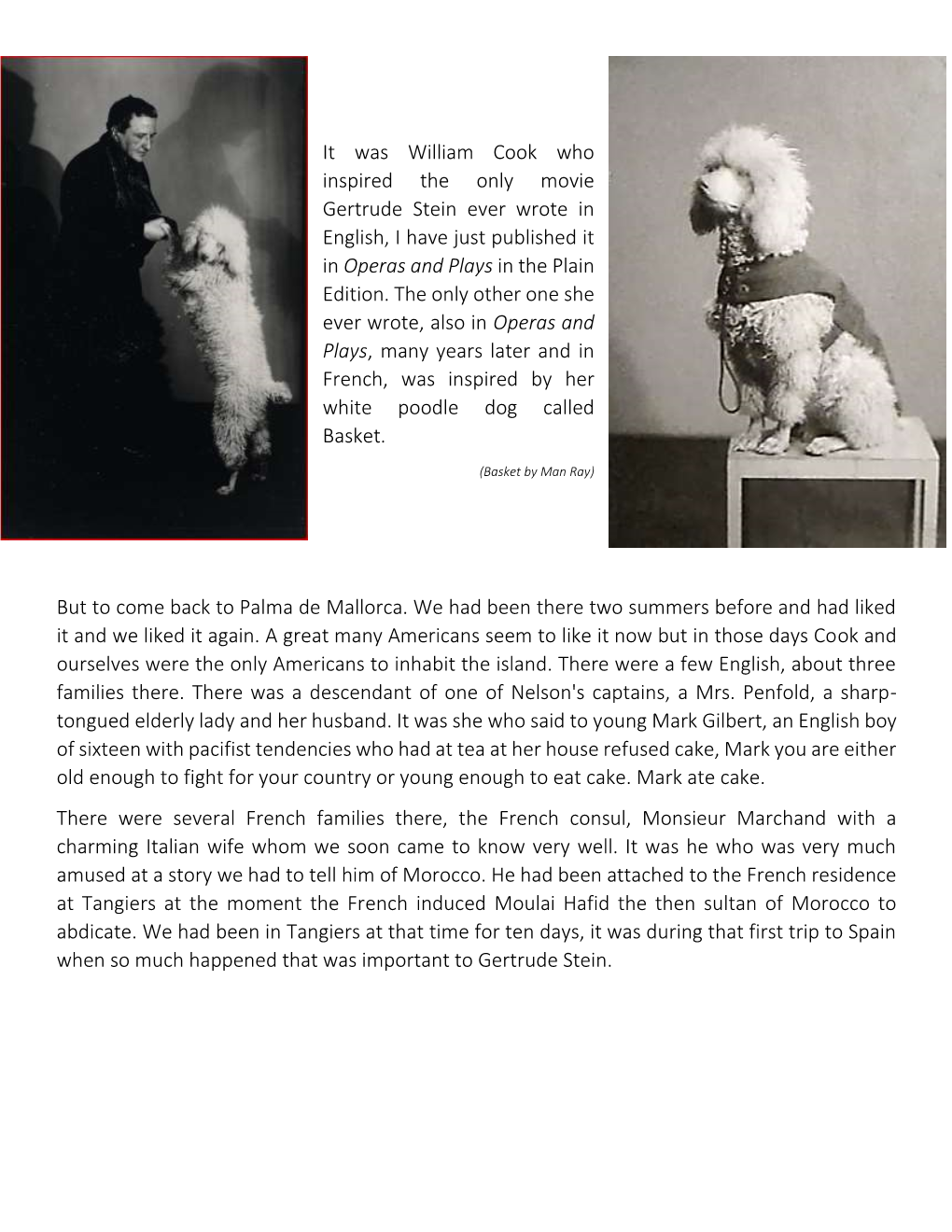

It Was William Cook Who Inspired the Only Movie Gertrude Stein Ever Wrote in English, I Have Just Published It in Operas and Plays in the Plain Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Humble Protest a Literary Generation's Quest for The

A HUMBLE PROTEST A LITERARY GENERATION’S QUEST FOR THE HEROIC SELF, 1917 – 1930 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jason A. Powell, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Steven Conn, Adviser Professor Paula Baker Professor David Steigerwald _____________________ Adviser Professor George Cotkin History Graduate Program Copyright by Jason Powell 2008 ABSTRACT Through the life and works of novelist John Dos Passos this project reexamines the inter-war cultural phenomenon that we call the Lost Generation. The Great War had destroyed traditional models of heroism for twenties intellectuals such as Ernest Hemingway, Edmund Wilson, Malcolm Cowley, E. E. Cummings, Hart Crane, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and John Dos Passos, compelling them to create a new understanding of what I call the “heroic self.” Through a modernist, experience based, epistemology these writers deemed that the relationship between the heroic individual and the world consisted of a dialectical tension between irony and romance. The ironic interpretation, the view that the world is an antagonistic force out to suppress individual vitality, drove these intellectuals to adopt the Freudian conception of heroism as a revolt against social oppression. The Lost Generation rebelled against these pernicious forces which they believed existed in the forms of militarism, patriotism, progressivism, and absolutism. The -

Gertrude Stein and Her Audience: Small Presses, Little Magazines, and the Reconfiguration of Modern Authorship

GERTRUDE STEIN AND HER AUDIENCE: SMALL PRESSES, LITTLE MAGAZINES, AND THE RECONFIGURATION OF MODERN AUTHORSHIP KALI MCKAY BACHELOR OF ARTS, UNIVERSITY OF LETHBRIDGE, 2006 A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of the University of Lethbridge in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of English University of Lethbridge LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA, CANADA © Kali McKay, 2010 Abstract: This thesis examines the publishing career of Gertrude Stein, an American expatriate writer whose experimental style left her largely unpublished throughout much of her career. Stein’s various attempts at dissemination illustrate the importance she placed on being paid for her work and highlight the paradoxical relationship between Stein and her audience. This study shows that there was an intimate relationship between literary modernism and mainstream culture as demonstrated by Stein’s need for the public recognition and financial gains by which success had long been measured. Stein’s attempt to embrace the definition of the author as a professional who earned a living through writing is indicative of the developments in art throughout the first decades of the twentieth century, and it problematizes modern authorship by re- emphasizing the importance of commercial success to artists previously believed to have been indifferent to the reaction of their audience. iii Table of Contents Title Page ………………………………………………………………………………. i Signature Page ………………………………………………………………………… ii Abstract ……………………………………………………………………………….. iii Table of Contents …………………………………………………………………….. iv Chapter One …………………………………………………………………………..... 1 Chapter Two ………………………………………………………………………….. 26 Chapter Three ………………………………………………………………………… 47 Chapter Four .………………………………………………………………………... 66 Works Cited .………………………………………………………………………….. 86 iv Chapter One Hostile readers of Gertrude Stein’s work have frequently accused her of egotism, claiming that she was a talentless narcissist who imposed her maunderings on the public with an undeserved sense of self-satisfaction. -

Inheriting the Yugoslav Century: Art, History, and Generation

Inheriting the Yugoslav Century: Art, History, and Generation by Ivana Bago Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Kristine Stiles, Supervisor ___________________________ Mark Hansen ___________________________ Fredric Jameson ___________________________ Branislav Jakovljević ___________________________ Neil McWilliam Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 ABSTRACT Inheriting the Yugoslav Century: Art, History, and Generation by Ivana Bago Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies Duke University ___________________________ Kristine Stiles, Supervisor ___________________________ Mark Hansen ___________________________ Fredric Jameson ___________________________ Branislav Jakovljević ___________________________ Neil McWilliam An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 Copyright by Ivana Bago 2018 Abstract The dissertation examines the work contemporary artists, curators, and scholars who have, in the last two decades, addressed urgent political and economic questions by revisiting the legacies of the Yugoslav twentieth century: multinationalism, socialist self-management, non- alignment, and -

Modern Illustrated Books

ARS LIBRI ELECTRONIC LIST #55 PARIS ANTIQUARIAN BOOK FAIR 2011 MODERN ILLUSTRATED BOOKS Ars Libri, Ltd. / 500 Harrison Ave. / Boston, MA 02118 [email protected] / www.arslibri.com / tel 617.357.5212 / fax 617.338.5763 Paris Antiquarian Book Fair 2011: Modern Illustrated books 1 1 (ARMORY SHOW) NEW YORK. ASSOCIATION OF AMERICAN PAINTERS AND SCULPTORS, INCORPORATED. Catalogue of the International Exhibition of Modern Art. At the Armory of the Sixty-Ninth Infantry... February fifteenth to March fifteenth, 1913 [cover title gives the opening date as February seventeenth]. Preface by Frederick James Gregg. 105, (7)pp. Orig. dec. wraps., printed in green, blue and brown with the pine-tree emblem of the exhibition. The original catalogue of the inaugural New York installation of the Armory Show, still the single most important event in the history of modern art in America. From the library of Robert C. Vose (of the Vose Galleries, Boston), with his signature on the front cover and at head of the first leaf, dated 1959, and titled by him at spine. First two leaves within a bit dog-eared at lower corner; otherwise a very clean and fresh copy. New York, 1913. $6,000.00 Karpel J314; Gordon II.666-676; cf. (among many accounts) Altschuler, Bruce: The Avant-Garde in Exhibition: New Art in the 20th Century (New York, 1994), p. 60ff. ARS LIBRI ELECTRONIC LIST #55 2 PARIS ANTIQUARIAN BOOK FAIR 2011 MODERN ILLUSTRATED BOOKS 2 2 ARP, HANS. Die Wolkenpumpe. (Sammlung “Die Silbergäule.” Band 50-51 [vere 52/53].) (28)pp. Sm. 4to. Orig. -

Oral History Interview with Paul Cadmus, 1988 March 22-May 5

Oral history interview with Paul Cadmus, 1988 March 22-May 5 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Paul Cadmus on March 22, 1988. The interview took place in Weston, Connecticut, and was conducted by Judd Tully for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview JUDD TULLY: Tell me something about your childhood. You were born in Manhattan? PAUL CADMUS: I was born in Manhattan. I think born at home. I don't think I was born in a hospital. I think that the doctor who delivered me was my uncle by marriage. He was Dr. Brown Morgan. JUDD TULLY: Were you the youngest child? PAUL CADMUS: No. I'm the oldest. I's just myself and my sister. I was born on December 17, 1904. My sister was born two years later. We were the only ones. We were very, very poor. My father earned a living by being a commercial lithographer. He wanted to be an artist, a painter, but he was foiled. As I say, he had to make a living to support his family. We were so poor that I suffered from malnutrition. Maybe that was the diet, too. I don't know. I had rickets as a child, which is hardly ever heard of nowadays. -

February 7, 2001

April 2019 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Keith de Lellis (212) 327-1482 [email protected] GEORGE PLATT LYNES PORTRAITS, NUDES, & DANCE APRIL 11 – MAY 23, 2019 Keith de Lellis Gallery showcases the portrait photography of noted fashion photographer and influential artist George Platt Lynes (American, 1907–1955) in its spring exhibition. Though largely concealed during his lifetime (or published under pseudonyms), Lynes’ male nude photographs are perhaps his most notable works today and inspired later artists such as Robert Mapplethorpe and Herb Ritts. Primarily self-taught, Lynes was influenced by Man Ray when he visited Paris in 1925, where he also met Monroe Wheeler, Glenway Wescott, and John Cocteau. Publisher Jack Woody wrote, “surrealism, neo-romanticism, and other European visual movements remained with him” when he returned to New York (Ballet: George Platt Lynes, Twelvetree Press, 1985). Lynes first exhibited with surrealist gallerist Julian Levy in 1932, and was featured at many galleries and museums in his lifetime, including three group exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art. He opened his New York studio in 1933, finding great success in commercial portraiture for fashion magazines (Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, etc.) and local elites. The artist relocated to Los Angeles in 1946 to lead Vogue’s west coast studio for two years, photographing celebrities such as Katharine Hepburn and Gloria Swanson, before returning to New York to focus on personal work, disavowing commercial photography. While his commercial work allowed him to support himself and brought him great recognition as a photographer, it did not fulfill him creatively, leading the artist to destroy many of those negatives and prints towards the end of his life. -

James S. Jaffe Rare Books Llc

JAMES S. JAFFE RARE BOOKS LLC P. O. Box 930 Deep River, CT 06417 Tel: 212-988-8042 Email: [email protected] Website: www.jamesjaffe.com Member Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America / International League of Antiquarian Booksellers All items are offered subject to prior sale. Libraries will be billed to suit their budgets. Digital images are available upon request. [ANTHOLOGY] JOYCE, James. Contact Collection of Contemporary Writers. (Edited by Robert McAlmon). 8vo, original printed wrappers. (Paris: Contact Editions Three Mountains Press, 1925). First edition, published jointly by McAlmon’s Contact Editions and William Bird’s Three Mountains Press. One of 300 copies printed in Dijon by Darantiere, who printed Joyce’s Ulysses. Slocum & Cahoon B7. With contributions by Djuna Barnes, Bryher, Mary Butts, Norman Douglas, Havelock Ellis, Ford Madox Ford, Wallace Gould, Ernest Hemingway, Marsden Hartley, H. D., John Herrman, Joyce, Mina Loy, Robert McAlmon, Ezra Pound, Dorothy Richardson, May Sinclair, Edith Sitwell, Gertrude Stein and William Carlos Williams. Includes Joyce’s “Work In Progress” from Finnegans Wake; Hemingway’s “Soldiers Home”, which first appeared in the American edition of In Our Time, Hanneman B3; and William Carlos Williams’ essay on Marianne Moore, Wallace B8. Front outer hinge cleanly split half- way up the book, not affecting integrity of the binding; bottom of spine slightly chipped, otherwise a bright clean copy. $2,250.00 BERRIGAN, Ted. The Sonnets. 4to, original pictorial wrappers, rebound in navy blue cloth with a red plastic title-label on spine. N. Y.: Published by Lorenz & Ellen Gude, 1964. First edition. Limited to 300 copies. A curious copy, one of Berrigan’s retained copies, presumably bound at his direction, and originally intended for Berrigan’s close friend and editor of this book, the poet Ron Padgett. -

Historic Tullamore Farm a True Town & Country Farm

AUCTION Historic Tullamore Farm A True Town & Country Farm September 20th 207.8+/- Acres Preserved Farmland Delaware Twp, Hunterdon County, NJ Private Pastoral Setting with Breathtaking Country and Delaware River Views • Located in the picturesque rolling Hunterdon County hillside and just steps to the Delaware River and Towpath Trail for walking, biking or riding horses. • Truly a diverse compound combining a lovely historic home site, equestrian center, guest cottages, event center, barns and farmland. • Wonderfully restored historic main stone house built in the 1800’s and later expanded features an open floor plan with expansive windows to take in the +/- beautiful rolling hills. 106.33 Acres • The main home features a chef’s kitchen with center island which opens to the dining room and great room with cathedral ceilings and French doors opening to an expansive patio. The master private wing features a spacious bedroom, cozy fireplace, dressing room, European en suite bath with soaking tub and office. There are two guest suites, plus two upstairs bedrooms with bathroom. • Host equestrian events! The Equestrian center includes indoor and outdoor riding arena, acres 101.47+/- Acres of paddocks, and two barns with 16 stalls plus apartment for trainer or laborers. • Rich productive soils. • The farm has been utilized as a grass-fed cattle operation and can easily be converted to a vineyard or other agritourism business. • Walk or Ride along the Delaware River towpath for access to Stockton, Lambertville, Frenchtown or cross the bridge -

Writing Communities: Aesthetics, Politics, and Late Modernist Literary Consolidation

WRITING COMMUNITIES: AESTHETICS, POLITICS, AND LATE MODERNIST LITERARY CONSOLIDATION by Elspeth Egerton Healey A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor John A. Whittier-Ferguson, Chair Associate Professor Kali A. K. Israel Associate Professor Joshua L. Miller Assistant Professor Andrea Patricia Zemgulys © Elspeth Egerton Healey _____________________________________________________________________________ 2008 Acknowledgements I have been incredibly fortunate throughout my graduate career to work closely with the amazing faculty of the University of Michigan Department of English. I am grateful to Marjorie Levinson, Martha Vicinus, and George Bornstein for their inspiring courses and probing questions, all of which were integral in setting this project in motion. The members of my dissertation committee have been phenomenal in their willingness to give of their time and advice. Kali Israel’s expertise in the constructed representations of (auto)biographical genres has proven an invaluable asset, as has her enthusiasm and her historian’s eye for detail. Beginning with her early mentorship in the Modernisms Reading Group, Andrea Zemgulys has offered a compelling model of both nuanced scholarship and intellectual generosity. Joshua Miller’s amazing ability to extract the radiant gist from still inchoate thought has meant that I always left our meetings with a renewed sense of purpose. I owe the greatest debt of gratitude to my dissertation chair, John Whittier-Ferguson. His incisive readings, astute guidance, and ready laugh have helped to sustain this project from beginning to end. The life of a graduate student can sometimes be measured by bowls of ramen noodles and hours of grading. -

Catalogue Littérature 11

NOUVELLE SÉRIE LITTÉRATURE ÉDITIONS ORIGINALES / LIVRES ILLUSTRÉS / D O C U M E N T S / R E V U E S 11 J.-F. Fourcade Livres anciens et modernes OCTOBRE-NOVEMBRE 2012 3, rue Beautreillis 75004 Paris Métro Sully Morland ou Saint Paul Tél. : 01 48-04-82-15 e-mail : [email protected] Les jours suivant l’envoi du catalogue, la librairie est ouverte tous les jours du lundi au samedi inclus de 11 h à 13 h 30 et de 16 h à 19 h Banque Bred Bastille 4260 01 884 IBAN : FR 76 1010 7001 0100 4260 1088 458 BIC : BREDFRPPXXX Nos conditions de vente sont conformes aux usages du SLAM et aux règlements de la LILA. Nous acceptons les cartes bancaires : Visa, Eurocard, Mastercard. SIRET : 512 162 140 00028 TVA : FR. 30512162140 Les livres et documents proposés dans ce catalogue sont tous en très bon état, sauf indication contraire. ATTENTION Désormais, la librairie est ouverte, en dehors des périodes de catalogue, de 16h à 19h et sur rendez-vous. Vous pouvez consulter et commander une sélection de livres et de documents en ligne sur notre site internet www.librairie-fourcade.com Achat au comptant de livres, d’autographes, de bibliothèques ou d’archives. ACTION ⁄ ARAGON / 16 / 3 1 / ACTION. N° 1. Dir. : Florent Fels et Marcel 7 / APOLLINAIRE (Guillaume). Anecdotiques. Sauvage. P., février 1920, in-4, br., 84 p. Textes de Max Préface de Marcel Adéma. P., N.R.F., 1955, in-12, rel. de Jacob, André Salmon, Georges Gabory, Florent Fels, l’éditeur, 332 p. -

Parker Tyler

Parker Tyler: An Inventory of His Collection at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Parker Tyler Tyler, Parker, 1904-1974 Title: Parker Tyler Collection Dates: 1910-1982 Extent: 59 document boxes, 4 oversize boxes (osb) (24.78 linear feet), 4 oversize folders (osf), 9 galley files (gf) Abstract: The Parker Tyler collection was created between 1910 and 1982 and comprises correspondence, manuscripts, proofs, photographs, diaries, clippings, and printed material documenting the life and career of the American film and art critic, poet and essayist Parker Tyler (1904-1974). Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-04300 Language: English, French, and Russian Access: Open for research. A small group of poems and letters are too fragile to handle. The original pages have been removed and replaced with photocopies. The originals are restricted from use and noted in the finding aid. Researchers must create an online Research Account and agree to the Materials Use Policy before using archival materials. Use Policies: Ransom Center collections may contain material with sensitive or confidential information that is protected under federal or state right to privacy laws and regulations. Researchers are advised that the disclosure of certain information pertaining to identifiable living individuals represented in the collections without the consent of those individuals may have legal ramifications (e.g., a cause of action under common law for invasion of privacy may arise if facts concerning an individual's private life are published that would be deemed highly offensive to a reasonable person) for which the Ransom Center and The University of Texas at Austin assume no responsibility. -

Vente Publique De Livres Samedi 26 Octobre A` 14 H

Dans la salle “LAETITIA” Avenue des Grenadiers 48 1050 Bruxelles VENTE PUBLIQUE DE LIVRES SAMEDI 26 OCTOBRE A` 14 H. Exposition gen´ erale:´ Vendredi 25 de 10 h. a` 19 h. sans interruption. OCTOBRE 2019 Samedi 26 de 9 h. 30 a` 12 h. CONDITIONS DE VENTES 1. La vente se fait strictement au comptant. Il ne sera accorde´ aucun credit.´ 2. Les acquereurs´ paieront 25 % en sus des encheres.` 3. Mesdames et Messieurs les acheteurs peuvent enlever soit pendant la vente, soit immediatement´ apres` la vente ; ainsi que le dimanche 27 octobre entre 9 et 11 h. Ou enfin, a` la Librairie des El´ ephants,´ 19 Place Van Meenen a` 1060 Bruxelles, a` partir du lundi qui suit a` partir de 15 h. 4. La Librairie des El´ ephants´ remplira, aux conditions d’usage, les ordres d’achat des amateurs qui ne peuvent assister a` la vente. 5. L’ordre de passage des lots sera respecte.´ 6. Tous les renseignements fournis par nous, le sont de bonne foi. 7. La marchandise ayant et´ e´ exposee´ pendant deux jours, les amateurs auront pu se rendre compte de son etat.´ Il ne sera admis, par consequent,´ aucune reclamation´ de quelque nature qu’elle soit, memeˆ si elle a pour object la description du lot au catalogue, et ce, pendant ou apres` l’adjudication. 8. Des` l’adjudication prononcee´ et quoique la Librairie des El´ ephants´ en prendra le meilleur soin, la marchandise se trouve sous l’entiere` responsabilite´ de l’acheteur, et sa disparition ou sa det´ erioration´ ne donneront droit a` aucun remboursement.