When There Was Another Me Harold Garde

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CMCA's New Home...Captures the Generous Forward-Looking Spirit of a Living Institution Whose Adventurous Mission Promises T

“CMCA’s new home...captures the generous forward-looking spirit of a living institution whose adventurous mission promises to enrich the cultural life of its city and region for decades to come.” —Henry N. Cobb, founding partner, Pei Cobb Freed & Partners PRESS INFORMATION Press Contact | Kristen N. Levesque +1 207 329 3090 | [email protected] 21 WINTER STREET, ROCKLAND, MAINE Table of Contents Over the course of its 65-year history, the Center for Maine Contemporary Art (CMCA) has introduced the work of hundreds of contemporary artists—both well known and emerging—to audiences in Maine and beyond. CMCA has begun a new chapter in contemporary art in the state of Maine. Its new home in the heart of Rockland’s downtown arts district is destined to be—in the words of artist Alex Katz—“a game-changer for Maine art.” The New CMCA 3 Contemporary Since 1952 4 A Legacy of Artists 5 An Active Community Participant 6 Extending CMCA’s Educational Impact 7 CMCA by the Numbers 8 2018 Exhibition Schedule 9 Rockland, Maine 10 Toshiko Mori Architect 11 CMCANOW.ORG 2 The New CMCA In summer 2016, CMCA opened a newly constructed 11,500+ square foot building, with 5,500 square feet of exceptional exhibition space, designed by award-winning architect Toshiko Mori, FAIA, (New York and North Haven, Maine). Located in the heart of downtown Rockland, Maine, across from the Farnsworth Art Museum and adjacent to the historic Strand Theatre, the new CMCA has three exhibition galleries (one which doubles as a lecture hall/performance space), a gift shop, ArtLab classroom, and a 2,200 square foot courtyard open to the public. -

Maine's Favorite

YOUR STUDENT. OUR COMMUNITY. “It’s “It’sa place a place that thatdemands demands personal personal OPEN DOORS. growthgrowth and andcommunity community growth. growth. Yes, Yes,we allwe grow all grow individually, individually, but webut we OPEN MINDS. simultaneouslysimultaneously grow grow as a ascommunity.” a community.” – Cheverus– Cheverus High HighSchool School alumnus, alumnus, class ofclass 2009 of 2009 We invite you along with your family to learn more about how Cheverus pieces together the strong foundation for post-secondary study with a values- based education, building both strong KNOWLEDGE CAN BE TESTED. KNOWLEDGE CAN BE TESTED. individual students and responsible A VALUES-BASED EDUCATION CHARACTER IS ACHIEVED. CHARACTER IS ACHIEVED. members of the community. Cheverus High School encourages our students to be people for Cheverus High School encourages its students to be people for others – persons who find happiness in sharing their talents, others – persons who find happiness in sharing their talents, especially with those who are less fortunate than they. By involving our especially with those who are less fortunate than they. By involving its OPEN HOUSE. students in supervised projects and programs, the school fosters growth students in supervised projects and programs, the school fosters growth in self-esteem, empathy toward others and personal maturity – OCTOBER 20, 2013 in self-esteem, empathy toward others and personal maturity – traits that can’t be tested on paper. By teaching our students to be 12–3 pm traits that can’t be tested on paper. By teaching its students to be sensitive to the disparate needs and expectations of their peers, sensitive to the disparate needs and expectations of their peers, Register online at teachers and families, Cheverus helps our students to become socially teachers and families, Cheverus helps its students to become socially cheverusopenhouse.org responsible members of their communities. -

A Publication of the Orlando Museum of Art Fy 2014-2015 Annual Report for the Fiscal Year July 1, 2014, Through June 30, 2015

ANNUAL REPORT A PUBLICATION OF THE ORLANDO MUSEUM OF ART FY 2014-2015 ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE FISCAL YEAR JULY 1, 2014, THROUGH JUNE 30, 2015 2 MISSION The mission of the Orlando Museum of Art is to inspire creativity, passion and intellectual curiosity by connecting people with art and new ideas. VISION The Orlando Museum of Art is to be a creative change agent for education and the center for artistic engagement, as well as a place for civic, cultural and economic development. PURPOSE The purpose of the Orlando Museum of Art is to interpret and present the most compelling art for the public to experience, and to positively affect people’s lives with innovative and inspiring education programs that will endure as a cultural legacy in Central Florida. ANNUAL REPORT l 2014-2015 3 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS S ANNUAL REPORT 2014-2015 3 Board of Trustees 6 Acquisitions, Loans & Deaccessions 9 Exhibitions and & Installations 14 Education & Public Programs 18 Volunteers 22 Fundraisers 26 Membership 27 Support 30 Publications 42 Retail 43 Audience Development & Special Events 45 Museum Staff 53 ANNUAL REPORT l 2014-2015 5 BOARD OF TRUSTEES 2014-2015 BOARD 2014-2015 TRUSTEES BUILDING/FACILITIES EX-OFFICIO TRUSTEES OFFICERS & EXECUTIVE Ted R. Brown, Esq. COMMITTEE President, Acquisition Trust COMMITTEE Christina E. Buntin Ben W. Subin, Esq., Chair Francine Newberg Tony L. Massey Celeste Byers Richard Kessler Chairman Patrick T. Christiansen, Esq. Richard E. Morrison President, Friends of Bruce Douglas P. Michael Reininger American Art Ted R. Brown, Esq. Robert B. Feldman, M.D. R. J. Santomassino William Forness, Jr., CPA Immediate Past Carolyn M. -

PRESS INFORMATION Press Contact | [email protected]

PRESS INFORMATION Press Contact | [email protected] "A Game-Changer for Maine Art." – Alex Katz 21 Winter Street, Rockland, Maine Public Opening | June 26, 2016 Over the course of its sixty-four year history, the Center for Maine Contemporary Art (CMCA) has introduced the work of hundreds of contemporary artists—both well known and emerging—to audiences in Maine. CMCA is now opening a whole new chapter in contemporary art in the state. Its compelling new home in the heart of Rockland’s downtown arts district is destined to be—in the words of artist Alex Katz—“a game-changer for Maine art.” The New CMCA 1 Contemporary Since 1952 2 A Legacy of Artists 3 An Active Community Participant 4 Extending CMCA’s Educational Impact 5 CMCA by the Numbers 6 2016 Opening Season Exhibitions 7 Rockland, Maine 8 Toshiko Mori Architect 9 The New CMCA In summer 2016, CMCA will open a newly constructed 11,500+ square foot building, with 5,500 square feet of exceptional exhibition space, designed by award-winning architect Toshiko Mori (New York and North Haven, Maine). Located in the heart of downtown Rockland, Maine, across from the Farnsworth Art Museum and adjacent to the historic Strand Theatre, the new CMCA has three exhibition galleries (one which doubles as a lecture hall/performance space), a gift shop, ArtLab classroom, and a 2,200 square feet open public courtyard. The new building and location enables CMCA to pursue its core mission of fostering contemporary art on a new and elevated level. The glass-enclosed space, with its corru- gated metal exterior and emphasis on Maine’s legendary light, is unlike anything else in the state. -

Fy 2015-2016

ANNUAL REPORT FY 2015-2016 A PUBLICATION OF THE ORLANDO MUSEUM OF ART Noelle Mason, Installation shot of Love Letters / White Flag: The Book of Good, 2009- 2016, hand-embroidered white handkerchiefs, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist. Noelle Mason, Installation shot of Through a glass, darkly (spring cleaning), 2016, Borax, combo desk, composition notebook, no. 2 pencil, 30 x 21 x 31 in. Courtesy of the artist. © Noelle Mason. Image courtesy of Raymond Martinot. ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE FISCAL YEAR JULY 1, 2015 THROUGH JUNE 30, 2016 Lynsey Addario, Baghdad After the Storm (detail), 2011. From the National Geographic exhibit Women of Vision. Women of Vision. is organized by and traveled by the National 2 Geographic Society. PNC Financial Services is the presenting national tour sponsor of Women of Vision. MISSION The mission of the Orlando Museum of Art is to inspire creativity, passion and intellectual curiosity by connecting people with art and new ideas. VISION The Orlando Museum of Art is to be a creative change agent for education and the center for artistic engagement, as well as a place for civic, cultural and economic development. PURPOSE The purpose of the Orlando Museum of Art is to interpret and present the most compelling art for the public to experience, and to positively affect people’s lives with innovative and inspiring education programs that will endure as a cultural legacy in Central Florida. ANNUAL REPORT l 2015-2016 3 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS S ANNUAL REPORT 2015-2016 3 Board of Trustees 6 Acquisitions, Loans & Deaccessions 9 Exhibitions and & Installations 16 Education & Public Programs 20 Support 24 Membership 30 Volunteers 32 Council of 101 Fundraisers 34 2015-2016 Audit 35 Publications 36 Retail 38 Audience Development & Special Events 40 Museum Staff 48 Image on left: John Singer Sargent Francis Brooks Chadwick, 1880 Oil on panel 13 3/4 x 9 7/8 in. -

Northeast Historic Film Videos of Life in New England

FREE LOAN PROGRAM Northeast Historic Film FREE LOAN PROGRAM Videos of Life in New England Length Title Category Year Format (min.) Description PERF Purchase Little Tree is a Native American from Connecticut, now a resident of Pittsford, Vermont. He says, "I am a Namante, one who heals by spiritual power, and a Matenu, one who heals by use of plants . Part of an Earth Medicine (1&2) American Indians 1975 DVD 56 eight part series on the use of plants and trees in health . PERF No Little Tree is a Native American from Connecticut, now a resident of Pittsford, Vermont. He says, "I am a Namante, one who heals by spiritual power, and a Matenu, one who heals by use of plants . Part of an Earth Medicine (3&4) American Indians 1975 DVD 56 eight part series on the use of plants and trees in health . PERF No Little Tree is a Native American from Connecticut, now a resident of Pittsford, Vermont. He says, "I am a Namante, one who heals by spiritual power, and a Matenu, one who heals by use of plants . Part of an Earth Medicine (5&6) American Indians 1975 DVD 56 eight part series on the use of plants and trees in health . PERF No Little Tree is a Native American from Connecticut, now a resident of Pittsford, Vermont. He says, "I am a Namante, one who heals by spiritual power, and a Matenu, one who heals by use of plants . Part of an Earth Medicine (7&8) American Indians 1975 DVD 56 eight part series on the use of plants and trees in health . -

Maine Painters, a Catalog Selected Exhibitions

Maine Painters, A Catalog Selected Exhibitions June 12 - October 24, 2015 Points of View: Photographs by Jay Gould, Gary Green, David Maisel and Shoshannah White Viewing elements of the Maine landscape from different levels of scale – from great distance to very close-up, the contemporary photographers in this exhibition explore different aspects of the interrelationships between human populations and the natural world. This exhibition is supported by a grant from the Davis Family Foundation. June 12, 2015 – March 26, 2016 Maine Collected This exhibition features works by some of the many contemporary artists represented in the permanent collection who live in or are Gary Green, Untitled (Terrain Vague), 2015, black and white photograph connected to Maine. This exhibition includes work in most media and in a wide variety of themes and styles, many of which have not been on view in the museum previously. Maine Collected, and The June 12 - October 24, 2015 Painter of Maine are companion exhibitions of Director’s Cut: The The Painter of Maine: Maine Art Museum Trail at the Portland Museum of Art from May Photographs of Marsden Hartley 21 – September 13. Marsden Hartley (1877-1943), a na- tive son of Lewiston Maine, is recog- November 6, 2015 – March 26, 2016 nized as one of the most important The View Out His Window (and in his mind’s eye): Photographs American modernists. This exhibition by Jeffery Becton focuses on images of artist, from A photographer and image-maker who lives on Deer Isle, a rocky and anonymous toned photographs of forested island off the coast of Maine, Jeffery Becton constructs him as a young man to images taken images about his surroundings, from extraordinary sweeping coastal by George Platt Lynes the last year views to internal life, both house interiors and the introspective of Hartley’s life. -

Never Let Anything Hold You Back the Spirit, Attitude & Determination of Sara Brown

Spring 2010 never let anything hold you back The spirit, attitude & determination of Sara Brown. uw & china INBRe piRi’S machine Features UWyo spring 2010 volume 11 number 3 The Taiwan Times from June 29, 1989, reporting on the wyoming Delegation’s visit. 2538 The This year is theof the story Cowboy—UW's headline continuing involvement with China This is a story teaser by byDave the Shelles author 18 Sara Brown—Never let anything hold you back by Dave Shelles 32 INBRE builds a better pipeline to biomedical research by Dave Shelles 36 Piri’s machine by Dave Shelles ON THE COVER UW doctoral student Sara Brown lost her leg in a smokejumping accident, but pushed onward with her recovery and is on schedule to earn her doctorate in 2011. departments UWyo spring 2010 volume 11 number 3 MAIN CONTRIBUTOR Main contributor text 4 VIEWPOINT 6 NEWS IN BRIEF 11 NEWS UPDATES 12 PORTRAIT UW's Flower Girls by Ted Brummond 14 SNAPSHOTS Jeffery Dannemiller Will Ross Gracie Lawson-Borders Mark Branch 40 ATHLETICS Stephanie Ortiz by Dave Shelles 42 ARTS Pete Simpson Jr. and Sr. perform in Hamlet by Dave Shelles 44 ALUMNI Catherine Keene by Tom Lacock minor contributor 46 GALLERY minor contributor text A modernist convergence at UW by Susan moldenhauer 48 OUTTAKES Rhiannon Lee Wenn studies in Knight Hall window by Trice megginson vieWPOINT UWYO Spring 2010 Volume 11 number 3 The Magazine for Alumni and Friends of the University of Wyoming e talk a lot about energy at the University of director of institutional communications WWyoming. -

Doing Time Captured Bibliography

www.philagrafika.org [email protected] Doing Time: Captured Bibliography The following is a selection of source material relating to the Philagrafika project Doing Time: Captured . This bibliography is a work-in-progress and we welcome additional suggestions. The Project Spanish artists Patricia Gómez and María Jesús González will create large-scale prints, photographs and related videos during a residency at the decommissioned Holmesburg Prison in Northeast Philadelphia. The prints will be a physical archive of the prison cells—the imprints literally taking the surface of wall—including paint, drawings and markings left by the inmates who lived there. Gómez and González see their practice as a form of printmaking in which the wall serves as a matrix. They remove paint from walls to record the markings that have been left there over time. Intervening in architectural spaces that will be demolished, their prints preserve surfaces that carry stories of the past, capturing the spirit and history of a place. The project will culminate in an exhibition at Moore College of Art & Design. Reference material is organized according to the following themes that inform our understanding of the artists’ work: I. Past Work by Gómez and González ……………………………………………….. 2 II. Influential Artists for Gómez and González ……..………….…..……………. 2-5 III. Monoprint …………………………………………………………….……………….... 5 IV. Documentary Photography and Film ……………………….……..………..….. 6 V. Conservation …………………………………………………….…….…..........….... 6-7 VI. The Prison as a Source for Contemporary Art …………………..………….. 7-10 VII. History of Holmesburg Prison …………………………..….........……………. 10-11 VIII. Incarceration ………………………………………………..…….....………..…… 11-14 Appendix: Other Resources …………………..………...….….....………...………. 14-15 Appendix: Contemporary Art at Eastern State Penitentiary ...................... 15-17 I. Past Work by Gómez and González The artists have applied this particular practice to several projects in Spain, creating prints of walls destined to be torn down. -

Harold Garde. Painting. 50 Years

Harold Garde. painting. 50 years. museum of florida art an appreciation. he popular stereotype requires artists to be iconoclasts, concerned not with Tmoney or material reward, but with Art, going where it and an individual vision lead, often unappreciated, defiant, fearless. Cowboys of the garret. Always measured against the great ear slicer. Of course, most artists are more like other people, finding caution to be the better part of valor, struggling to make pictures that the market will bear because they would love to be able to make a living from their art. And most would prefer to be associated with, but not be of, the artist myth, admiring those few who are courageous, who make no concessions to prettiness or fashion, whose singleness of purpose inspires us all to tell more truth, to examine more deeply and honestly our own lives for what is personally and profoundly human. Harold Garde, though, is the real thing, far more than the stereotype, but lending credence to it—an artist of passion, integrity, commitment, unafraid of failure, unable to compromise his vision. He personifies the myth, believing totally in the personal and social necessity of art. He gives other artists courage. —robert SHetterly “What makes Garde’s paintings work is the forceful handling of paint, the abrasive color and brushstroke ultimately dominating the jarring subject matter.” — Carl Little, Art New England, Boston, Massachuesetts “Be On ‘GArde’ for BriLLiAnCe. Garde peels back the membrane of the daily life. What he finds is the pulsing sense of consciousness itself.” —Laura Stewart, fine art writer, The Daytona Beach News-Journal, daytona, florida HArold GArde. -

Activereports Document

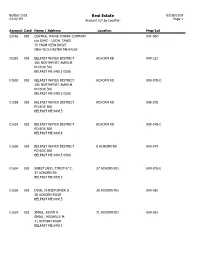

Belfast 2018 Real Estate 02/06/2019 02:02 PM Account List by Location Page 1 Account Card Name / AddressLocation Map/Lot 03765001 CENTRAL MAINE POWER COMPANY 00T-00D c/o IUMC - LOCAL TAXES 70 FARM VIEW DRIVE NEW GLOUCESTER ME 04260 00283001 BELFAST WATER DISTRICT ACHORN RD 009-120 285 NORTHPORT AVENUE PO BOX 506 BELFAST ME 04915 0506 01603001 BELFAST WATER DISTRICT ACHORN RD 009-078-D 285 NORTHPORT AVENUE PO BOX 506 BELFAST ME 04915 0506 01598001 BELFAST WATER DISTRICT ACHORN RD 009-078 PO BOX 506 BELFAST ME 04915 01601001 BELFAST WATER DISTRICT ACHORN RD 009-078-C PO BOX 506 BELFAST ME 04914 01605001 BELFAST WATER DISTRICT 8 ACHORN RD 009-079 PO BOX 506 BELFAST ME 04915 0506 01604001 SWEETLAND, TIMOTHY C. 37 ACHORN RD 009-078-E 37 ACHORN RD BELFAST ME 04915 01606001 DYER, CHRISTOPHER D 38 ACHORN RD 009-080 38 ACHORN ROAD BELFAST ME 04915 01607001 SMALL, KEVIN R. 71 ACHORN RD 009-081 SMALL, MICHELLE M. 71 ACHORN ROAD BELFAST ME 04915 Belfast 2018 Real Estate 02/06/2019 02:02 PM Account List by Location Page 2 Account Card Name / AddressLocation Map/Lot 01608 001 PEACH, HENRY E LIVING TRUST DATED 72 ACHORN RD 009-082 PEACH, HENRY E, NOWERS, DEBORAH K 72 ACHORN RD BELFAST ME 04915 01621001 GURNEY, CARROLL 79 ACHORN RD 009-086-D GURNEY, HAROLD c/o Matthew Hill, DHHS-OACPDS 91 CAMDEN ST. ROCKLAND ME 04841 01620001 MOREAU, ROGER 83 ACHORN RD 009-086-C 83 ACHORN RD BELFAST ME 04915 01609001 SYLVESTER, PAUL 84 ACHORN RD 009-082-A 84 ACHORN ROAD BELFAST ME 04915 00863001 PERRYMAN FAMILY TRUST DATED ADNEY PLACE 004-055-A PERRYMAN, WILLIAM D, PERRYMAN, 3 ADNEY PLACE BELFAST ME 04915 04192001 PERRYMAN FAMILY TRUST DATED 1 ADNEY PLACE 004-055-B PERRYMAN, WILLIAM D, PERRYMAN, 3 ADNEY PLACE BELFAST ME 04915 00862 001 PERRYMAN FAMILY TRUST DATED 3 ADNEY PLACE 004-055 PERRYMAN, WILLIAM D, PERRYMAN, 3 ADNEY PLACE BELFAST ME 04915 04107001 HOWARD, DOROTHY E AIRMAIL LANE 026-015-B 5 AIRMAIL LANE BELFAST ME 04915 00256001 Krohne, Paul Wm & Carryl Ann (TR) 4 AIRMAIL LANE 026-015 P.W. -

2014 Artists Listing

HOME HOME MAINE GUIDE SUBSCRIBE MAGAZINE ADVERTISE Search Features Magazine 2014 ARTISTS LISTING Features FEATURE-April 2014 Profiles By Britta Konau Sustainable Fresh From the Studio History Spaces Style Room Showcase The Canvas Drawing Board Letter From the Editor AIA Design Theory Design Wire Bright-Minded Home Shop Talk Outtake Web Exclusives On Newsstands Join the Conversation on Facebook DUANE PALUSKA, Bach, 2013, acrylic and canvas on wood, 24” x 26” For this year’s artists listing we searched for the freshest work by well-established and emerging or underrecognized artists alike. So who better to ask about what’s happening in Maine studios right now but the artists themselves? We asked 37 well-known and highly respected artists what they are currently working on and whether they are deepening a commitment to a longer exploration or going in new directions. We learned about some surprising new developments from artists whose work we thought we knew so well. For others, that kind of change comes more gradually, maybe even unnoticed until it has happened. None have run out of fresh ideas to explore. We also asked each of these established practitioners to suggest one artist with a connection to Maine who could be described as emerging or deserving of more recognition from curators, critics, and collectors alike. So another 35 artists joined this listing and were asked the same question: what are you working on right now? While these artists are generally younger, the terms “emerging” and “underrecognized” suggest complexities beyond questions of age or self-description. Does the label “emerging artist” imply importance of critical recognition, or is it an acknowledgment of recently finding a unique voice? The reasons these particular artists were chosen by the more established ones vary widely and are often intriguing—sometimes a perceived afnity in artistic outlook, in other cases, for working in an exactly opposite direction, but most frequently, simply appreciation of a fellow artist’s endeavor.