ABLE Major Workshop June 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table 7: Species Changing IUCN Red List Status (2014-2015)

IUCN Red List version 2015.4: Table 7 Last Updated: 19 November 2015 Table 7: Species changing IUCN Red List Status (2014-2015) Published listings of a species' status may change for a variety of reasons (genuine improvement or deterioration in status; new information being available that was not known at the time of the previous assessment; taxonomic changes; corrections to mistakes made in previous assessments, etc. To help Red List users interpret the changes between the Red List updates, a summary of species that have changed category between 2014 (IUCN Red List version 2014.3) and 2015 (IUCN Red List version 2015-4) and the reasons for these changes is provided in the table below. IUCN Red List Categories: EX - Extinct, EW - Extinct in the Wild, CR - Critically Endangered, EN - Endangered, VU - Vulnerable, LR/cd - Lower Risk/conservation dependent, NT - Near Threatened (includes LR/nt - Lower Risk/near threatened), DD - Data Deficient, LC - Least Concern (includes LR/lc - Lower Risk, least concern). Reasons for change: G - Genuine status change (genuine improvement or deterioration in the species' status); N - Non-genuine status change (i.e., status changes due to new information, improved knowledge of the criteria, incorrect data used previously, taxonomic revision, etc.); E - Previous listing was an Error. IUCN Red List IUCN Red Reason for Red List Scientific name Common name (2014) List (2015) change version Category Category MAMMALS Aonyx capensis African Clawless Otter LC NT N 2015-2 Ailurus fulgens Red Panda VU EN N 2015-4 -

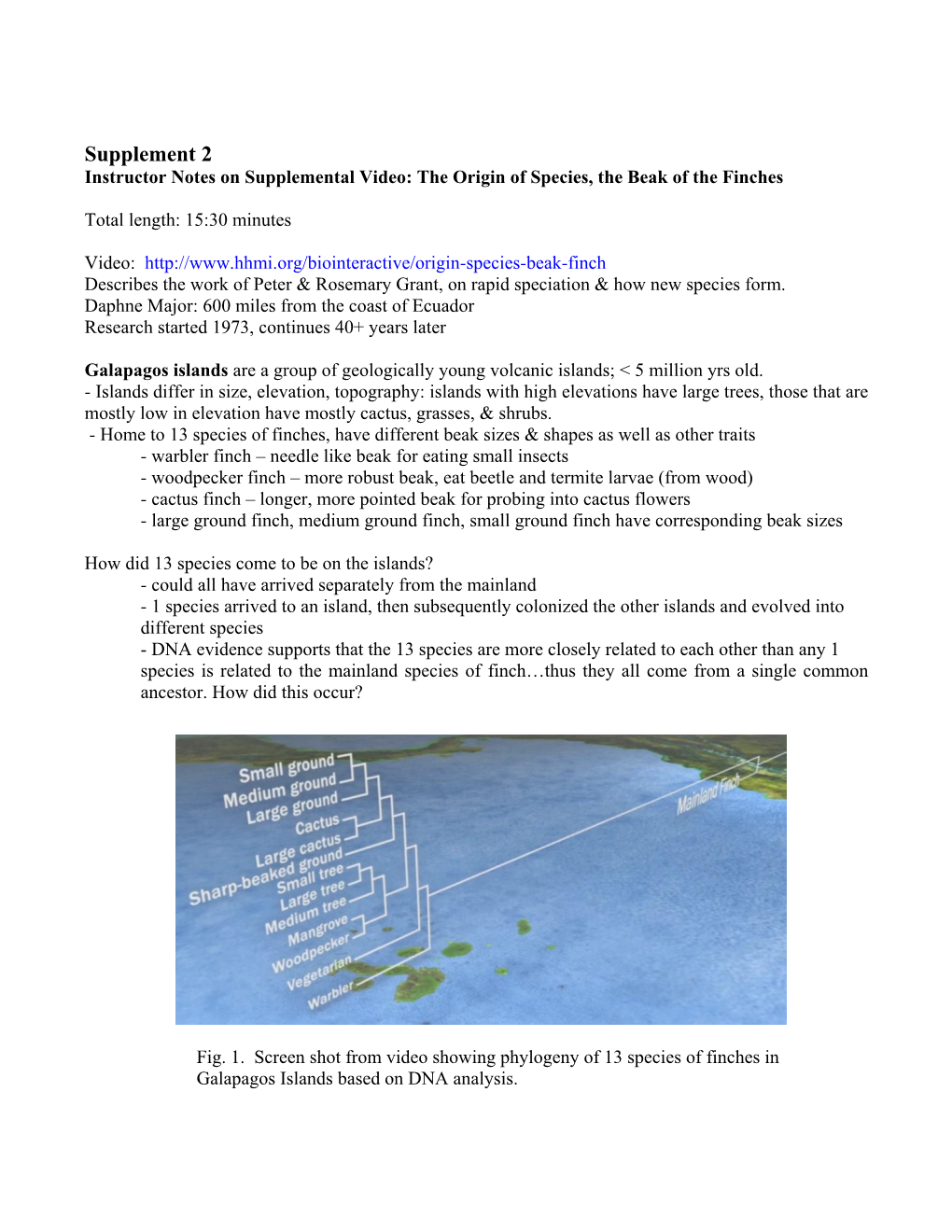

Ecuador & the Galapagos Islands

Ecuador & the Galapagos Islands - including Sacha Lodge Extension Naturetrek Tour Report 29 January – 20 February 2018 Medium Ground-finch Blue-footed Booby Wire-tailed Manakin Galapagos Penguin Green Sea Turtle Report kindly compiled by Tour participants Sally Wearing, Rowena Tye, Debbie Hardie and Sue Swift Images courtesy of David Griffiths, Sue Swift, Debbie Hardie, Jenny Tynan, Rowena Tye, Nick Blake and Sally Wearing Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf’s Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Ecuador & the Galapagos Islands - including Sacha Lodge Extension Tour Leader in the Galapagos: Juan Tapia with 13 Naturetrek Clients This report has kindly been compiled by tour participants Sally Wearing, Rowena Tye, Debbie Hardie and Sue Swift. Day 1 Monday 29th January UK to Quito People arrived in Quito via Amsterdam with KLM or via Madrid with Iberia, while Tony came separately from the USA. Everyone was met at the airport and taken to the Hotel Vieja Cuba; those who were awake enough went out to eat before a good night’s rest. Day 2 Tuesday 30th January Quito. Weather: Hot and mostly sunny. The early risers saw the first few birds of the trip outside the hotel: Rufous- collared Sparrow, Great Thrush and Eared Doves. After breakfast, an excellent guide took us on a bus and walking tour of Quito’s old town. This started with the Basilica del Voto Nacional, where everyone marvelled at the “grotesques” of native Ecuadorian animals such as frigatebirds, iguanas and tortoises. -

Darwin's Theory of Evolution Through Natural Selection

THE EVOLUTION OF LIFE NOTEBOOK Darwin’s Theory of Evolution Through Natural Selection OBSERVING PHENOMENA Phenomenon: Darwin found many kinds of finches with different sized and shaped beaks on the different islands of the Galápagos. 1. What questions do you have about this phenomenon? 1 - Darwin’s Voyage on the Beagle 1. What did Darwin see in South America that surprised him? 2. What was Lyell’s argument about Earth’s land features and what did it cause Darwin to question about the mountains? © Teachers’ Curriculum Institute Darwin’s Theory of Evolution Through Natural Selection 1 NOTEBOOK 2 - Darwin Visits the Galápagos Islands 1. What did many the species of animals in the Galapagos island resemble? 2. What is a trait? Give one example of a trait. 2 Darwin’s Theory of Evolution Through Natural Selection © Teachers’ Curriculum Institute NOTEBOOK INVESTIGATION 1 1. Which tool is a model for which bird’s beak? Match them below. Tools A. toothpick B. tweezers C. nail clippers D. pliers Tool Finch Large ground finch Vegetarian finch Cactus finch Woodpecker finch 2. Keep track of how many of each bird there are after each round. Station 1 Finch Before Round 1 After Round 1 After Round 2 Large ground finch 1 Vegetarian finch 1 Cactus finch 1 Woodpecker finch 1 Station 2 Finch Before Round 1 After Round 1 After Round 2 Large ground finch 1 Vegetarian finch 1 Cactus finch 1 Woodpecker finch 1 © Teachers’ Curriculum Institute Darwin’s Theory of Evolution Through Natural Selection 3 NOTEBOOK Station 3 Finch Before Round 1 After Round 1 After Round 2 Large ground finch 1 Vegetarian finch 1 Cactus finch 1 Woodpecker finch 1 Station 4 Finch Before Round 1 After Round 1 After Round 2 Large ground finch 1 Vegetarian finch 1 Cactus finch 1 Woodpecker finch 1 3. -

The Galapagos Islands DAY by DAY ITINERARY D+A 8 Days – 7 Nights

The Galapagos Islands DAY BY DAY ITINERARY D+A 8 days – 7 nights D Our Galapagos itineraries offer unforgettable experiences, with our SOUTH weekly departures allowing you to experience 3, 4, 7, and up to 14 + nights tours including: full board, two daily guided excursions with optional activities such as snorkeling, kayaking, dinghy rides and our A NORTH - CENTRAL new feature daily diving tours for license-holding divers. 8 Days / 7 Nights Wednesday: San Cristobal Airport pm. Interpretation Center & Tijeretas (San Cristobal Island). Thursday: am. Cerro Brujo (San Cristobal Island) GENOVESA pm. Pitt Point (San Cristobal Island ) Darwin Bay Friday: El Barranco, am. Suarez Point (Española Island) Prince pm. Gardner Bay, Osborn or Gardner Islets Philip’s Steps (Española Island) Saturday: am. Cormorant Point, Devil’s Crown or Champion Islet (Floreana Island) pm.Post Office (Floreana Island) Sunday: am. Pit Craters (Santa Cruz) pm. Charles Darwin Research Station & Fausto Llerena Breeding Center (Santa Cruz Island) Monday: Buccaneer Cove am. Dragon Hill (Santa Cruz Island) pm. Bartolome Island Tuesday: am. Rabida Island pm. Buccaneer Cove & Espumilla Beach (Santiago Island) Wednesday: am. Back Turtle Cove (Santa Cruz Island) Baltra Airport Pit Craters Charles Darwin Research Station Kicker Rock Champion Islet Gardner Islets DAY 1 - WEDNESDAY am - San Cristobal Airport Departure from Quito or Guayaquil to San Cristobal (2 1/2 hours flight). Arriving in Galapagos, passengers are picked up at the airport by our naturalist guides and taken to the pier to board the M/Y Coral I or M/Y Coral II. pm – Interpretation Center & Tijeretas Hill (San Cristobal Island) Dry landing in Puerto Baquerizo Moreno, the capital of the Galapagos Islands. -

The Galápagos Islands: Relatively Untouched, but Increa- Singly Endangered Las Islas Galápagos: Relativamente Intactas, Pero Cada Vez Más Amenaza- Das Markus P

284 CARTA AL EDITOR The Galápagos Islands: relatively untouched, but increa- singly endangered Las Islas Galápagos: relativamente intactas, pero cada vez más amenaza- das Markus P. Tellkamp DOI. 10.21931/RB/2017.02.02.2 Hardly any place on the planet evokes a sense of adaptive radiation. No matter which way one choo- mystique and wonder like the Galápagos Islands (Figu- ses to look at these birds, the Hawaiian honeycreeper re 1). They are the cradle of evolutionary thought. They (Fringillidae: Drepanidinae) radiation is by far the also are home to an unusual menagerie of animals, more spectacular: about 40 colorful species of birds, such as prehistoric-looking iguanas that feed on algae, some of which do (or did) not bear any resemblance giant tortoises, the only species of penguin to live on to a ‘typical’ finch, occupy a variety of niches, feeding the equator, a flightless cormorant, a group of unique on nectar, snails, insects, fruits, leaves or combinations an famous finches, furtive and shy rice rats, sea lions thereof1. Despite the magnificence of honeycreepers, and fur seals. Visitors have to be careful not to step on the more commonly known example of adaptive ra- the oxymoronically extremely tame wildlife. Endemic diation is that of the Galápagos finches (Thraupidae). plants, such as tree-like cacti, Scalesia trees and shrubs A look at the current conservation status of these two (relatives of sunflowers and daisies), and highland Mi- groups of birds may reveal why. Of the 35 species of ho- conia shrubs cover different island life zones. Around neycreeper listed by the IUCN, representing only the the world, people may not have heard much of Ecua- historically known species, 16 are extinct, 12 are criti- dor, the small South American country that proudly cally endangered, two endangered, and the remaining calls the islands its own, but they likely have heard of five vulnerable2. -

Can Darwin's Finches and Their Native Ectoparasites Survive the Control of Th

Insect Conservation and Diversity (2017) 10, 193–199 doi: 10.1111/icad.12219 FORUM & POLICY Coextinction dilemma in the Galapagos Islands: Can Darwin’s finches and their native ectoparasites survive the control of the introduced fly Philornis downsi? 1 2 MARIANA BULGARELLA and RICARDO L. PALMA 1School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand and 2Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington, New Zealand Abstract. 1. The survival of parasites is threatened directly by environmental alter- ation and indirectly by all the threats acting upon their hosts, facing coextinction. 2. The fate of Darwin’s finches and their native ectoparasites in the Galapagos Islands is uncertain because of an introduced avian parasitic fly, Philornis downsi, which could potentially drive them to extinction. 3. We documented all known native ectoparasites of Darwin’s finches. Thir- teen species have been found: nine feather mites, three feather lice and one nest mite. No ticks or fleas have been recorded from them yet. 4. Management options being considered to control P. downsi include the use of the insecticide permethrin in bird nests which would not only kill the invasive fly larvae but the birds’ native ectoparasites too. 5. Parasites should be targeted for conservation in a manner equal to that of their hosts. We recommend steps to consider if permethrin-treated cotton sta- tions are to be deployed in the Galapagos archipelago to manage P. downsi. Key words. Chewing lice, coextinction, Darwin’s finches, dilemma, ectoparasites, feather mites, Galapagos Islands, permethrin, Philornis downsi. Introduction species have closely associated species which are also endangered (Dunn et al., 2009). -

And Socio-Ecology of Wild Goffin's Cockatoos (Cacatua Goffiniana)

Behaviour 156 (2019) 661–690 brill.com/beh Extraction without tooling around — The first comprehensive description of the foraging- and socio-ecology of wild Goffin’s cockatoos (Cacatua goffiniana) M. O’Hara a,∗, B. Mioduszewska a,b, T. Haryoko c, D.M. Prawiradilaga c, L. Huber a and A. Auersperg a a Comparative Cognition, Messerli Research Institute, University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, Medical University Vienna, University of Vienna, Veterinaerplatz 1, 1210 Vienna, Austria b Max Planck Institute for Ornithology, Eberhard-Gwinner-Straße, 82319 Seewiesen, Germany c Research Center for Biology, Indonesian Institute of Sciences, Jl. Raya Jakarta - Bogor Km.46 Cibinong 16911 Bogor, Indonesia *Corresponding author’s e-mail address: [email protected] Received 7 June 2018; initial decision 14 August 2018; revised 8 October 2018; accepted 9 October 2018; published online 24 October 2018 Abstract When tested under laboratory conditions, Goffin’s cockatoos (Cacatua goffiniana) demonstrate numerous sophisticated cognitive skills. Most importantly, this species has shown the ability to manufacture and use tools. However, little is known about the ecology of these cockatoos, en- demic to the Tanimbar Islands in Indonesia. Here we provide first insights into the feeding- and socio-ecology of the wild Goffin’s cockatoos and propose potential links between their behaviour in natural settings and their advanced problem-solving capacities shown in captivity. Observational data suggests that Goffin’s cockatoos rely on a large variety of partially seasonal resources. Further- more, several food types require different extraction techniques. These ecological and behavioural characteristics fall in line with current hypotheses regarding the evolution of complex cognition and innovativeness. -

How Birds Use Tools by Celeste Silling Usually, Birds Are Limited by the Tools They Are Born With- Their Beaks, Wings, Claws, Et

How Birds Use Tools By Celeste Silling Usually, birds are limited by the tools they are born with- their beaks, wings, claws, etc. But some birds have learned to make use of other objects to help them hunt or forage. We humans tend to think of tools as things reserved for only the most advanced creatures like ourselves or apes. But birds might just be smarter than we think. Birds have most often been seen using tools to hunt or forage. The Woodpecker Finch in the Galapagos Islands is a classic example of this. These finches are not born with a woodpecker’s long and dexterous beak, but they have still found a way to hunt the same types of prey deep in cervices. The Woodpecker Finch uses long twigs or cactus thorns to poke into holes in the trees or ground and pry out insects or larvae. Several other bird species, like Green Jays and Chickadees have also been seen using sticks to forage. Other species have been known to use the combination of gravity and hard objects to get their meals. If you live near the shore, you might’ve seen a seagull dropping a shellfish on the rocks or pavement. This is an act of ingenuity, not clumsiness, as the force of the drop often opens up the hard shell for the gull to eat the insides. Similarly, Egyptian Vultures drop stones on Ostrich eggs to crack the shells without spilling too much of the yummy insides. Another tool that some birds use is bait. Burrowing Owls have occasionally been known to gather up dung from other animals and put it around their burrows. -

Recent Conservation Efforts and Identification of the Critically Endangered Mangrove Finch Camarhynchus Heliobates in Galápagos Birgit Fessl, Michael Dvorak, F

Cotinga 33 Recent conservation efforts and identification of the Critically Endangered Mangrove Finch Camarhynchus heliobates in Galápagos Birgit Fessl, Michael Dvorak, F. Hernan Vargas and H. Glyn Young Received 21 January 2010; final revision accepted 12 October 2010 first published online 16 March 2011 Cotinga 33 (2011): 27–33 El Pinzón de Manglar Camarhynchus heliobates es la especie más rara del grupo de los pinzones de Darwin, y su distribución está restringida a los manglares de la costa de Isabela. Aproximadamente 100 individuos sobreviven y están amenazados principalmente por la depredación de la rata introducida Rattus rattus y por el parasitismo de la mosca Philornis downsi. Un amplio programa de conservación se inició en 2006 con el fin de estudiar las aves sobrevivientes, reducir sus amenazas y restaurar la especie en sitios históricos donde anteriormente se la registró. Un número creciente de pinzones en los sitios donde actualmente existe significará mayores probabilidades de dispersión a los sitios históricos. La identificación correcta es necesaria para seguir y monitorear la dispersión de las aves. Esta publicación pretende ayudar a la identificación de la especie y da pautas para distinguirla del Pinzón Carpintero Camarhynchus pallidus, una especie estrechamente emparentada al Pinzón de Manglar. Las dos especies pueden distinguirse por el patrón de coloración de la cabeza y por su canto fácilmente diferenciable. Mangrove Finch Camarhynchus heliobates was the A second population persists on the south-east last species of Darwin’s finches to be described13. coast around Bahía Cartago (7 in Fig. 1; c.300 ha; Known historically from at least five different Figs. -

WILDLIFE CHECKLIST Reptiles the Twenty-Two Species of Galapagos

WILDLIFE CHECKLIST Reptiles The twenty-two species of Galapagos reptiles belong to five families, tortoises, marine turtles, lizards/iguanas, geckos and Clasifications snakes. Twenty of these species are endemic to the * = Endemic archipelago and many are endemic to individual islands. The Islands are well-known for their giant tortoises ever since their R = Resident discovery and play an important role in the development of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution. The name "Galapagos" M = Migrant originates from the spanish word "galapago" that means saddle. * Santa Fe land Iguana Conolophus pallidus Iguana Terrestre de Santa Fe * Giant Tortoise (11 Geochelone elephantopus Tortuga Gigante subspecies) M Pacific Green Sea Chelonia mydas Tortuga Marina Turtle * Marine Iguana * (7 Amblyrhynchus cristatus Iguana Marina subspecies) * Galapagos land Conolophus subcristatus Iguana Terrestre Iguana * Lava lizard (7 species) Tropidurus spp Lagartija de Lava Phyllodactylus * Gecko (6 species) Gecko galapagoensis * Galapagos snake (3 Culebras de Colubridae alsophis species) Galapagos Sea Birds The Galapagos archipelago is surrounded by thousands of miles of open ocean which provide seabirds with a prominent place in the fauna of the Islands . There are 19 resident species (5 are endemic), most of which are seen by visitors. There may be as many as 750,000 seabirds in Galapagos, including 30% of the world's blue-footed boobies, the world's largest red- footed booby colony and perhaps the largest concentration of masked boobies in the world (Harris, -

Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B

Downloaded from http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on February 29, 2016 Feeding innovations in a nested phylogeny of Neotropical passerines rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org Louis Lefebvre, Simon Ducatez and Jean-Nicolas Audet Department of Biology, McGill University, 1205 avenue Docteur Penfield, Montre´al, Que´bec, Canada H3A 1B1 Several studies on cognition, molecular phylogenetics and taxonomic diversity Research independently suggest that Darwin’s finches are part of a larger clade of speciose, flexible birds, the family Thraupidae, a member of the New World Cite this article: Lefebvre L, Ducatez S, Audet nine-primaried oscine superfamily Emberizoidea. Here, we first present a new, J-N. 2016 Feeding innovations in a nested previously unpublished, dataset of feeding innovations covering the Neotropi- phylogeny of Neotropical passerines. Phil. cal region and compare the stem clades of Darwin’s finches to other neotropical Trans. R. Soc. B 371: 20150188. clades at the levels of the subfamily, family and superfamily/order. Both in http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0188 terms of raw frequency as well as rates corrected for research effort and phylo- geny, the family Thraupidae and superfamily Emberizoidea show high levels of innovation, supporting the idea that adaptive radiations are favoured when Accepted: 25 November 2015 the ancestral stem species were flexible. Second, we discuss examples of inno- vation and problem-solving in two opportunistic and tame Emberizoid species, One contribution of 15 to a theme issue the Barbados bullfinch Loxigilla barbadensis and the Carib grackle Quiscalus ‘Innovation in animals and humans: lugubris fortirostris in Barbados. We review studies on these two species and argue that a comparison of L. -

FEATURED PHOTO POSSIBLE TOOL USE by a Williamson's

FEATURED PHOTO POSSIBLE TOOL USE BY A WILLIAMSOn’S SAPSUCKER ANTHONY J. BRAKE and YVONNE E. MCHUGH, 1201 Brickyard Way, Richmond, California 94801; [email protected] Tool use has been demonstrated in a number of avian species (Lefebvre et al. 2002). Perhaps the best-known example is the Woodpecker Finch (Camarhynchus pallidus) of the Galápagos Islands, which breaks off cactus spines or twigs for use in extracting wood-boring insects (Eibl-Eibesfeldt 1961, Eibl-Eibesfeldt and Sielman 1962, Tebbich et al. 2002). New Caledonian Crows (Corvus moneduloides) display exceptional skill in selecting, manufacturing, and utilizing objects to obtain food items that they are otherwise unable to reach (Hunt 1996). In North America, Brown-headed Nuthatches (Sitta pusilla) have been observed to use flakes of pine bark to remove other pieces of bark in order to capture insects underneath (Morse 1968, Pranty 1995). All of the above behaviors are considered true tool use in that they involve a tool being held directly by the beak or foot of the bird (Lefebvre et al. 2002). Numerous woodpecker species have been observed to use “anvils” such as tree forks or crevices into which food items are wedged to facilitate consumption (Bondo et al. 2008). Most such cases represent proto-anvils consisting of natural crevices. Great Spotted Woodpeckers (Dendrocopos major), however, use “true anvils” that they excavate in tree trunks. Here we report observations of a Williamson’s Sapsucker (Sphyrapicus thyroideus) using a wood flake for foraging. We observed this behavior at the Mono Mills Historic Site in Inyo National Forest, approximately 16 km southeast of Lee Vining in Mono County, California.