The Privatization of Our Democracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bee Round 3 Bee Round 3 Regulation Questions

USHB Nationals Bee 2016-2017 Bee Round 3 Bee Round 3 Regulation Questions (1) In an odd phase, this man complained that as he was taking \a hasty plate of soup," a letter arrived from William Marcy. This general reluctantly ordered the executions of several members of the Saint Patrick's Battalion, a group of Irish-American deserters. He staged the first large-scale amphibious assault in U.S. history and later successfully assaulted the fort of Chapultepec. The President reluctantly replaced Zachary Taylor with this man, who successfully took Mexico City during the Mexican-American War. For the point, what veteran general was nicknamed \Old Fuss and Feathers"? ANSWER: Winfield Scott (2) This program's unofficial newspaper was the Melvin Ryder produced Happy Days. The only two heads of it were both veterans of the International Association of Machinists, with the first being Robert Fechner. The former war hero Alvin York served in it while working at Cumberland Mountain State Park. Enrollees in this program planted nearly three billion trees and were required to send at least 25 out of 30 dollars a month home to their families. For the point, what New Deal program put unemployed, single men to work at manual labor camps? ANSWER: Civilian Conservation Corps (or CCC) (3) A hero of this conflict, Miles Morgan, sheltered panicked citizens in his fortified home. A potential cause of this conflict was the murder of John Sassamon, who had informed the governor of a potential attack. Near the end of this war, John Alderman killed the opposing leader near Mount Hope. -

A History of Maryland's Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016

A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 Published by: Maryland State Board of Elections Linda H. Lamone, Administrator Project Coordinator: Jared DeMarinis, Director Division of Candidacy and Campaign Finance Published: October 2016 Table of Contents Preface 5 The Electoral College – Introduction 7 Meeting of February 4, 1789 19 Meeting of December 5, 1792 22 Meeting of December 7, 1796 24 Meeting of December 3, 1800 27 Meeting of December 5, 1804 30 Meeting of December 7, 1808 31 Meeting of December 2, 1812 33 Meeting of December 4, 1816 35 Meeting of December 6, 1820 36 Meeting of December 1, 1824 39 Meeting of December 3, 1828 41 Meeting of December 5, 1832 43 Meeting of December 7, 1836 46 Meeting of December 2, 1840 49 Meeting of December 4, 1844 52 Meeting of December 6, 1848 53 Meeting of December 1, 1852 55 Meeting of December 3, 1856 57 Meeting of December 5, 1860 60 Meeting of December 7, 1864 62 Meeting of December 2, 1868 65 Meeting of December 4, 1872 66 Meeting of December 6, 1876 68 Meeting of December 1, 1880 70 Meeting of December 3, 1884 71 Page | 2 Meeting of January 14, 1889 74 Meeting of January 9, 1893 75 Meeting of January 11, 1897 77 Meeting of January 14, 1901 79 Meeting of January 9, 1905 80 Meeting of January 11, 1909 83 Meeting of January 13, 1913 85 Meeting of January 8, 1917 87 Meeting of January 10, 1921 88 Meeting of January 12, 1925 90 Meeting of January 2, 1929 91 Meeting of January 4, 1933 93 Meeting of December 14, 1936 -

GEORGE W. BUSH Recent Titles in Greenwood Biographies Halle Berry: a Biography Melissa Ewey Johnson Osama Bin Laden: a Biography Thomas R

GEORGE W. BUSH Recent Titles in Greenwood Biographies Halle Berry: A Biography Melissa Ewey Johnson Osama bin Laden: A Biography Thomas R. Mockaitis Tyra Banks: A Biography Carole Jacobs Jean-Michel Basquiat: A Biography Eric Fretz Howard Stern: A Biography Rich Mintzer Tiger Woods: A Biography, Second Edition Lawrence J. Londino Justin Timberlake: A Biography Kimberly Dillon Summers Walt Disney: A Biography Louise Krasniewicz Chief Joseph: A Biography Vanessa Gunther John Lennon: A Biography Jacqueline Edmondson Carrie Underwood: A Biography Vernell Hackett Christina Aguilera: A Biography Mary Anne Donovan Paul Newman: A Biography Marian Edelman Borden GEORGE W. BUSH A Biography Clarke Rountree GREENWOOD BIOGRAPHIES Copyright 2011 by ABC-CLIO, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rountree, Clarke, 1958– George W. Bush : a biography / Clarke Rountree. p. cm. — (Greenwood biographies) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-313-38500-1 (hard copy : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-313-38501-8 (ebook) 1. Bush, George W. (George Walker), 1946– 2. United States— Politics and government—2001–2009. 3. Presidents—United States— Biography. I. Title. E903.R68 2010 973.931092—dc22 [B] 2010032025 ISBN: 978-0-313-38500-1 EISBN: 978-0-313-38501-8 15 14 13 12 11 1 2 3 4 5 This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. -

Grassroots, Geeks, Pros, and Pols: the Election Integrity Movement's Rise and the Nonstop Battle to Win Back the People's Vote, 2000-2008

MARTA STEELE Grassroots, Geeks, Pros, and Pols: The Election Integrity Movement's Rise and the Nonstop Battle to Win Back the People's Vote, 2000-2008 A Columbus Institute for Contemporary Journalism Book i MARTA STEELE Grassroots, Geeks, Pros, and Pols Grassroots, Geeks, Pros, and Pols: The Election Integrity Movement's Rise and the Nonstop Battle to Win Back the People's Vote, 2000-2008 Copyright© 2012 by Marta Steele. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews. For information, address the Columbus Institute for Contemporary Journalism, 1021 E. Broad St., Columbus, Ohio 43205. The Columbus Institute for Contemporary Journalism is a 501(c) (3) nonprofit organization. The Educational Publisher www.EduPublisher.com BiblioPublishing.com ISBN:978-1-62249-026-4 ii Contents FOREWORD By Greg Palast …….iv PREFACE By Danny Schechter …….vi INTRODUCTION …….ix By Bob Fitrakis and Harvey Wasserman ACKNOWLEDGMENTS …...xii AUTHOR’S INTRODUCTION …..xix CHAPTER 1 Origins of the Election ….….1 Integrity Movement CHAPTER 2A Preliminary Reactions to ……..9 Election 2000: Academic/Mainstream Political CHAPTER 2B Preliminary Reactions to ……26 Election 2000: Grassroots CHAPTER 3 Havoc and HAVA ……40 CHAPTER 4 The Battle Begins ……72 CHAPTER 5 Election 2004 in Ohio ……99 and Elsewhere CHAPTER 6 Reactions to Election 2004, .….143 the Scandalous Firing of the Federal -

The Election That Could Break America

The Election That Could Break America theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/11/what-if-trump-refuses-concede/616424 Barton Gellman, The Atlantic, September 23, 2020 There is a cohort of close observers of our presidential elections, scholars and lawyers and political strategists, who find themselves in the uneasy position of intelligence analysts in the months before 9/11. As November 3 approaches, their screens are blinking red, alight with warnings that the political system does not know how to absorb. They see the obvious signs that we all see, but they also know subtle things that most of us do not. Something dangerous has hove into view, and the nation is lurching into its path. The danger is not merely that the 2020 election will bring discord. Those who fear something worse take turbulence and controversy for granted. The coronavirus pandemic, a reckless incumbent, a deluge of mail-in ballots, a vandalized Postal Service, a resurgent effort to suppress votes, and a trainload of lawsuits are bearing down on the nation’s creaky electoral machinery. Something has to give, and many things will, when the time comes for casting, canvassing, and certifying the ballots. Anything is possible, including a landslide that leaves no doubt on Election Night. But even if one side takes a commanding early lead, tabulation and litigation of the “overtime count”—millions of mail-in and provisional ballots—could keep the outcome unsettled for days or weeks. If we are lucky, this fraught and dysfunctional election cycle will reach a conventional stopping point in time to meet crucial deadlines in December and January. -

2013-2014 Wisconsin Blue Book

STATISTICS: HISTORY 677 HIGHLIGHTS OF HISTORY IN WISCONSIN History — On May 29, 1848, Wisconsin became the 30th state in the Union, but the state’s written history dates back more than 300 years to the time when the French first encountered the diverse Native Americans who lived here. In 1634, the French explorer Jean Nicolet landed at Green Bay, reportedly becoming the first European to visit Wisconsin. The French ceded the area to Great Britain in 1763, and it became part of the United States in 1783. First organized under the Northwest Ordinance, the area was part of various territories until creation of the Wisconsin Territory in 1836. Since statehood, Wisconsin has been a wheat farming area, a lumbering frontier, and a preeminent dairy state. Tourism has grown in importance, and industry has concentrated in the eastern and southeastern part of the state. Politically, the state has enjoyed a reputation for honest, efficient government. It is known as the birthplace of the Republican Party and the home of Robert M. La Follette, Sr., founder of the progressive movement. Political Balance — After being primarily a one-party state for most of its existence, with the Republican and Progressive Parties dominating during portions of the state’s first century, Wisconsin has become a politically competitive state in recent decades. The Republicans gained majority control in both houses in the 1995 Legislature, an advantage they last held during the 1969 session. Since then, control of the senate has changed several times. In 2009, the Democrats gained control of both houses for the first time since 1993; both houses returned to Republican control in 2011. -

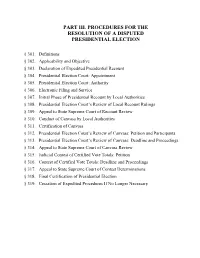

Part Iii. Procedures for the Resolution of a Disputed Presidential Election

PART III. PROCEDURES FOR THE RESOLUTION OF A DISPUTED PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION § 301. Definitions § 302. Applicability and Objective § 303. Declaration of Expedited Presidential Recount § 304. Presidential Election Court: Appointment § 305. Presidential Election Court: Authority § 306. Electronic Filing and Service § 307. Initial Phase of Presidential Recount by Local Authorities § 308. Presidential Election Court’s Review of Local Recount Rulings § 309. Appeal to State Supreme Court of Recount Review § 310. Conduct of Canvass by Local Authorities § 311. Certification of Canvass § 312. Presidential Election Court’s Review of Canvass: Petition and Participants § 313. Presidential Election Court’s Review of Canvass: Deadline and Proceedings § 314. Appeal to State Supreme Court of Canvass Review § 315. Judicial Contest of Certified Vote Totals: Petition § 316. Contest of Certified Vote Totals: Deadline and Proceedings § 317. Appeal to State Supreme Court of Contest Determinations § 318. Final Certification of Presidential Election § 319. Cessation of Expedited Procedures If No Longer Necessary PART III. PROCEDURES FOR THE RESOLUTION OF A DISPUTED PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION 1 Introductory Note: These Procedures for the Resolution of a Disputed Presidential 2 Election (hereinafter “Procedures”) address the unique challenges that exist when a presidential 3 election remains unsettled more than 24 hours after the polls have closed and, despite the reporting 4 of preliminary returns on Election Night and into the next day, one (or both) of the two leading 5 candidates has issued a public statement proclaiming that the race is not yet over. This situation 6 raises the possibility that the unsettled election will turn into a disputed election, as occurred in 7 2000, with the candidates and their campaigns using available procedures, including judicial 8 litigation, in an effort to secure a victory. -

Fighting for Voting Rights, Again – Billmoyers.Com

2/5/2021 Fighting for Voting Rights, Again – BillMoyers.com MOYERS ON DEMOCRACY Fighting for Voting Rights, Again Bill Moyers talk with John Bonifaz and Ben Clements of Free Speech for People BY BILLMOYERS.COM TEAM | OCTOBER 28, 2020 Moyers on Democracy Bill Moyers talks with John Bonifaz… Cookie policy 8.5K ANNOUNCER: Welcome to Moyers on Democracy. This election season is being waged in the middle of a pandemic of Covid-19 and an epidemic of voter suppression. The first kills people. The second kills democracy. We have seen the courage of front-line workers confronting the virus. But we have heard too little of the front-line fighters for voting rights. You’ll hear two in this episode as Bill Moyers talks with John Bonifaz and Ben Clements. They lead the non-profit organization Free Speech for People whose mission includes defending the integrity of our elections. John Bonifaz has been on the frontlines of key voting rights battles for more than 20 years. He co-founded Free Speech for People and serves as its President. Ben Clements chairs the Board of Directors as well as its https://billmoyers.com/story/fighting-for-voting-rights-again/ 1/22 2/5/2021 Fighting for Voting Rights, Again – BillMoyers.com legal committee. A former prosecutor, he served as Chief Legal Counsel to the governor of Massachusetts and is a founding partner of the law firm, Clements Law in Boston. Here to talk with John Bonifaz and Ben Clements is Bill Moyers. BILL MOYERS: Hi Ben. Hi John. It’s good to be with both of you. -

A Practical Guide to Defending the Constitution in a Contested 2020 Election

A practical guide to defending the Constitution in a contested 2020 election by Zack Malitz, Brandon Evans, and Becky Bond Last updated October 14, 2020 Contact us at [email protected] PREFACE “Get rid of the ballots and you’ll have a very peaceful — there won’t be a transfer, frankly. There will be a continuation.” – Donald Trump, September 23, 2020 “Rule #1: Believe the autocrat.” – Masha Gessen, Autocracy: Rules for Survival Introduction written October 11, 2020 We are days away from the most important election of our lifetimes. If everyone is able to vote and every vote is counted, Donald Trump will lose this election. But, if Joe Biden doesn’t win in a landslide, a narrow margin of victory may not be sufficient to ensure that Biden is sworn in as our next president. We believe that in a close election, Trump is likely to try to overturn the results of the election by disrupting the normally perfunctory process of casting and counting Electoral College votes. If that happens, we will be in dangerous and uncharted waters. Many people are skeptical that it will come to this. They argue that Trump will try to save face by claiming the election was rigged against him but won’t try to hang on to power after losing an election. After all, there’s no precedent for a president attempting to seize power in spite of losing an election. In the United States, none of our elections have been fully free and fair – many people have been and continue to be denied full voting rights – but after every presidential election in our history a loser has conceded to a winner and worked to accomplish a peaceful transition of power. -

Proto-Fascism Unleashed: How the Republican Party Sold Its Soul and Now Threatens Democracy

COMMENTARY Proto-Fascism Unleashed: How the Republican Party Sold its Soul and now Threatens Democracy BY THOMAS PALLEY JUNE 2021 1. A Faustian bargain This essay argues that some forty years ago the Republican Party struck a Faustian bargain whereby it traded integrity and decency for tax cuts and a corporate dominated economy. Now, the party is reaping the consequences of that bargain in the form of its capture by Donald Trump and his followers. How- ever, it also means we are all threatened as the party has unleashed and legitimized neo-fascist tendencies that stand to destroy democracy and tolerance and replace them with authoritarianism and intolerance. 2. Triumph of the Big Lie Recently (May 12, 2021) the U.S. Republican Congressional delegation expelled Rep. Liz Cheney (R-WY) from her position as their No.3 leader. Cheney is the daughter of former Vice-President Dick Cheney, who was himself a former Republican Wyoming Congressman and was a leader in the Neoconservative takeover of Washington’s foreign policy establishment. That speaks to her extraordinary conservative Republican pedigree, yet still she was removed from her position. Her offenses were twofold. First, denying Donald Trump’s dishonest claim to have won the No- vember 2020 election. Second, voting for Trump’s impeachment for his role in promoting the insurrec- tion of January 6, 2021. Cheney’s dismissal marks another step for the U.S. down the road to fascism, and the echoes with the Germany’s Nazi experience grow louder every day. With her dismissal, the Republican Party has officially accepted Trump as their “Fuhrer” and shown itself to be entirely beholden to him. -

New 2017 Strip & Flip .Pages

!1 Five Jim Crows & Electronic Election Theft Trump Edition of The Strip & Flip Selection of 2016 Prologue The disaster of America's 2016 election was defined by three basic elements: the stripping of very large numbers of eligible American citizens from the voter rolls; the flipping of electronic vote counts; and the Electoral College. These poisons have been with us in various manifestations since the birth of our nation. They have undermined our democracy and plunged our country into dire authoritarian straits. They've determined not just the presidency but the makeup of the US Congress, the Supreme Court and overall judiciary, city, state and local governments, and much more. They've taken control of our government away from the people and handed it to a cynical band of manipulative corporatists who have stripped our voter rolls and flipped our electronic outcomes, with disastrous results. This book outlines the historic roots of this disaster, including the systemic disenfranchisement (mostly by race) of large sections of the American electorate through the birth of slavery, the Revolution, the Civil War, birth of Jim Crow segregation and beyond. It also provides a set of answers: We need to win universal automatic voter registration; transparent voter rolls; a four-day national holiday for voting; ample locations for all citizens to conveniently cast ballots; universal hand-counted paper ballots; automatic recounts free to all candidates; abolition of the Electoral College; an end to gerrymandering; a ban on corporate money in our campaigns. There's more. But that's a good start. In 2016, some 29 Republican secretaries of state used a computer program called Crosscheck to strip countless citizens from the voter rolls. -

The Founders' Bush V. Gore

THE FOUNDERS’ BUSH V. GORE: THE 1792 ELECTION DISPUTE AND ITS CONTINUING RELEVANCE E DWARD B. FOLEY* INTRODUCTION: THE GAP IN OUR CONSTITUTIONAL ARCHITECTURE The 2000 presidential election re-exposed a critical weakness in the Constitution’s procedures for determining the winner of the presidency when the outcome is disputed. The Constitution says only that, with both houses of Congress present, the Vice President of the United States (acting as president of the Senate) shall open the certificates of the Electoral College votes sent from the states, “and the votes shall then be counted.”1 Using the passive voice, this clause suggests, without specifying clearly, that the Vice President holds the authority to resolve any dispute over counting the Electoral College votes from the states.2 Yet the Vice President may well be one of the competing candidates seeking the office of the presidency, as Al Gore was in 2000, and it is an obvious conflict of interest to give this individual the authority to decide the dispute. This indeterminate constitutional clause, however, offers no obvious alternative. Do the two houses of Congress vote together as a single combined body, a procedure not contemplated elsewhere in the Constitution and, to my knowledge, unheard of in the practices that have unfolded since the Founding? Surely, the Framers of the Constitution would have spelled out this unusual procedure with a bit more specificity if that is what they had in mind. Yet suppose the two houses vote separately, as is the regular practice with Congress. What if the two houses are split on the issue in dispute? The question of which candidate won the presidency is not like a piece of legislation, which can die unenacted if the two houses do not agree.