Anti-China Rhetoric, Presidential Elections and Us Foreign

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nominations Of: Ronald Sims, Fred P. Hochberg, Helen R

S. HRG. 111–173 NOMINATIONS OF: RONALD SIMS, FRED P. HOCHBERG, HELEN R. KANOVSKY, DAVID H. STEVENS, PETER KOVAR, JOHN D. TRASVIN˜A, AND DAVID S. COHEN HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON BANKING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON NOMINATIONS OF: RONALD SIMS, OF WASHINGTON, TO BE DEPUTY SECRETARY, DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT FRED P. HOCHBERG, OF NEW YORK, TO BE PRESIDENT AND CHAIRMAN, EXPORT-IMPORT BANK HELEN R. KANOVSKY, OF MARYLAND, TO BE GENERAL COUNSEL, DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT DAVID H. STEVENS, OF VIRGINIA, TO BE ASSISTANT SECRETARY FOR HOUSING–FEDERAL HOUSING COMMISSIONER, DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT PETER KOVAR, OF MARYLAND, TO BE ASSISTANT SECRETARY FOR CONGRESSIONAL AND INTERGOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS, DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT JOHN D. TRASVIN˜ A, OF CALIFORNIA, TO BE ASSISTANT SECRETARY FOR FAIR HOUSING AND EQUAL OPPORTUNITY, DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT DAVID S. COHEN, OF MARYLAND, TO BE ASSISTANT SECRETARY FOR TERRORIST FINANCING, DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY APRIL 23, 2009 Printed for the use of the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs ( Available at: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate/senate05sh.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 53–677 PDF WASHINGTON : 2009 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON BANKING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AFFAIRS CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut, Chairman TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota RICHARD C. -

Gitmo Hs Doc3

USA ‘I HAVE NO REASON TO BELIEVE THAT I WILL EVER LEAVE THIS PRISON ALIVE’ INDEFINITE DETENTION AT GUANTÁNAMO CONTINUES; 100 DETAINEES ON HUNGER STRIKE Amnesty International Publications First published in May 2013 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org Copyright Amnesty International Publications 2013 Index: AMR 51/022/2013 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. Amnesty International is a global movement of 3 million people in more than 150 countries and territories, who campaign on human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments. We research, campaign, advocate and mobilize to end abuses of human rights. Amnesty International is independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion. Our work is largely financed by contributions from our membership and donations Table of Contents ‘It is not a surprise to me that we’ve got problems in Guantánamo’ .................................... 1 History of a hunger striker ............................................................................................ -

US-China Relations

U.S.-China Relations: An Overview of Policy Issues Susan V. Lawrence Specialist in Asian Affairs August 1, 2013 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41108 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress U.S.-China Relations: An Overview of Policy Issues Summary The United States relationship with China touches on an exceptionally broad range of issues, from security, trade, and broader economic issues, to the environment and human rights. Congress faces important questions about what sort of relationship the United States should have with China and how the United States should respond to China’s “rise.” After more than 30 years of fast-paced economic growth, China’s economy is now the second-largest in the world after that of the United States. With economic success, China has developed significant global strategic clout. It is also engaged in an ambitious military modernization drive, including development of extended-range power projection capabilities. At home, it continues to suppress all perceived challenges to the Communist Party’s monopoly on power. In previous eras, the rise of new powers has often produced conflict. China’s new leader Xi Jinping has pressed hard for a U.S. commitment to a “new model of major country relationship” with the United States that seeks to avoid such an outcome. The Obama Administration has repeatedly assured Beijing that the United States “welcomes a strong, prosperous and successful China that plays a greater role in world affairs,” and that the United States does not seek to prevent China’s re-emergence as a great power. -

Democracy, Strategic Interests & U.S. Foreign Policy in the Arab World: A

1 The University of Washington Bothell Democracy, Strategic Interests & U.S. Foreign Policy in the Arab World: A Multiple Case Study of Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan & Saudi Arabia Kelly Berg A Capstone project presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Policy Studies through the School of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences June 2015 2 Abstract What determines U.S. foreign policy in the Arab world? In order to address this question, an inductive multiple case study of Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan and Saudi Arabia was conducted. These four Arab countries were selected due to their varying political positions and relationships with the U.S. I argue that the U.S.’s prioritization of strategic interests trumps or, in some cases, stifles support for the democratic process within the context of U.S. foreign policy in the Arab world, and that “democracy” is only advocated for when it serves U.S. desire for stability and hegemony throughout the region. Examining Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia demonstrates that political stability in the region, resistance to terrorism and unrest, Israel’s interests, and economic gains through oil and weapon production and sales are the U.S.’s key priorities. The results of this study will contribute to the existing literature by providing a comprehensive assessment of complex interdependence and political incongruences in U.S. foreign policy in the Arab world. 3 Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor and mentor, Professor Karam Dana, whose encouragement, advice, wisdom, and support proved to be invaluable to my academic journey. -

1601Qus China.Pdf

Comparative Connections A Triannual E-Journal on East Asian Bilateral Relations US-China Relations: Navigating Friction, Forging Cooperation Bonnie Glaser, CSIS/Pacific Forum CSIS Alexandra Viers, CSIS The South China Sea remained the most contentious issue in the US-China relationship in the early months of 2016. North Korea’s fourth nuclear test and missile launches posed both a challenge and an opportunity. After two months of intense consultations, the US and China struck a deal that led to unprecedentedly tough sanctions on Pyongyang. Xi Jinping attended the Nuclear Security Summit in Washington DC at the end of March and held a bilateral meeting with President Obama. Their joint statements called for cooperation on nuclear security and climate change. Relations between the militaries hit a snag as Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter postponed a planned visit to China and Beijing rejected a request for a US aircraft carrier battle group to visit Hong Kong. Talks continued on a bilateral investment treaty, but China failed to submit a new “negative list,” leaving prospects uncertain for concluding a BIT by the end of Obama’s term. South China Sea continues to cause friction Tensions between the US and China over the South China Sea simmered throughout the first four months of 2016 as a ruling neared in the case brought by the Philippines against China over Beijing’s maritime claims. The first episode took place at the end of January when a US guided- missile destroyer, the USS Curtis Wilbur, conducted a freedom of navigation (FON) operation within 12nm of Triton Island in the Paracel Island chain. -

The Obama Administration and the Prospects for a Democratic Presidency in a Post-9/11 World

NYLS Law Review Vols. 22-63 (1976-2019) Volume 56 Issue 1 Civil Liberties 10 Years After 9/11 Article 2 January 2012 The Obama Administration and the Prospects for a Democratic Presidency in a Post-9/11 World Peter M. Shane The Ohio State University Moritz College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/nyls_law_review Part of the Law and Politics Commons, Law and Society Commons, Military, War, and Peace Commons, and the National Security Law Commons Recommended Citation Peter M. Shane, The Obama Administration and the Prospects for a Democratic Presidency in a Post-9/11 World, 56 N.Y.L. SCH. L. REV. 28 (2011-2012). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Law Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. VOLUME 56 | 2011/12 PETER M. SHANE The Obama Administration and the Prospects for a Democratic Presidency in a Post-9/11 World ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Jacob E. Davis and Jacob E. Davis II Chair in Law, The Ohio State University Moritz College of Law. 27 THE PROSpeCTS FOR A DemoCRATIC PRESIdeNCY IN A POST-9/11 WORld [W]hen I won [the] election in 2008, one of the reasons I think that people were excited about the campaign was the prospect that we would change how business is done in Washington. And we were in such a hurry to get things done that we didn’t change how things got done. And I think that frustrated people. -

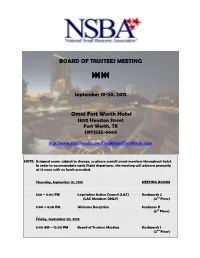

Completeboardpackets

BOARD OF TRUSTEES MEETING September 19-20, 2013 Omni Fort Worth Hotel 1300 Houston Street Fort Worth, TX (817)535-6664 http://www.omnihotels.com/FindAHotel/FortWorth.aspx NOTE: Assigned rooms subject to change, so please consult event monitors throughout hotel. In order to accommodate early flight departures, the meeting will adjourn promptly at 12 noon with no lunch provided. Thursday, September 19, 2013 MEETING ROOMS 300 – 5:00 PM Legislative Action Council (LAC) Stockyards 2 (LAC Members ONLY) (2nd Floor) 5:00 – 6:30 PM Welcome Reception Sundance II (3rd Floor) Friday, September 20, 2013 8:00 AM – 12:00 PM Board of Trustees Meeting Stockyards 1 (2nd Floor) BOARD OF TRUSTEES MEETING Friday, September 20, 2013 8:30 AM – 12:00 PM Omni Fort Worth Hotel (1300 Houston Street) Room: Stockyards 1 Fort Worth, Texas AGENDA TOPICS WELCOME DAVID ICKERT SECRETARY’S REPORT MIKE MITTERNIGHT 1) Approve Minutes of 6/18/2013 Board Meeting TREASURER’S REPORT TIM REYNOLDS 1) Updated Financials a) Income Statement b) Balance Sheet CHAIR’S REPORT DAVID ICKERT 1) Executive Committee STRATEGIC PLANNING COMMITTEE LARRY NANNIS NOMINATING COMMITTEE CHRIS HOLMAN ADVOCACY COOKIE DRISCOLL 1) Tax Policy 2) Economic Development 3) Environment and Regulatory Affairs 4) Health and Human Resources 5) Other Issues September 2013 NSBA Board Packet 2 Back to Agenda BOARD AGENDA PAGE 2 COMMUNICATIONS PEDRO ALFONSO 1) Media 2) Surveys and Mid-Year Economic Report 3) Communications Audit & Membership Survey MEMBERSHIP 1) Small Business Leadership Council ERIC TOLBERT a) Draft PowerPoint Presentation 2) New Health Program: TABS 3) Membership Update SMALL BUSINESS TECHNOLOGY COUNCIL JERE GLOVER SMALL BUSINESS EXPORTERS ASSOCIATION DAVID ICKERT COUNCIL OF REGIONAL EXECUTIVES ROB FOWLER OTHER BUSINESS ADJOURN September 2013 NSBA Board Packet 3 Back to Agenda MINUTES OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES MEETING June 18, 2013 Westin City Center Washington, D.C. -

The Anglo-America Special Relationship During the Syrian Conflict

Open Journal of Political Science, 2019, 9, 72-106 http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojps ISSN Online: 2164-0513 ISSN Print: 2164-0505 Beyond Values and Interests: The Anglo-America Special Relationship during the Syrian Conflict Justin Gibbins1, Shaghayegh Rostampour2 1Zayed University, Dubai, UAE 2Brandeis University, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA How to cite this paper: Gibbins, J., & Abstract Rostampour, S. (2019). Beyond Values and Interests: The Anglo-America Special Rela- This paper attempts to reveal how intervention in international conflicts (re) tionship during the Syrian Conflict. Open constructs the Anglo-American Special Relationship (AASR). To do this, this Journal of Political Science, 9, 72-106. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojps.2019.91005 article uses Syria as a case study. Analyzing parliamentary debates, presiden- tial/prime ministerial speeches and formal official addresses, it offers a dis- Received: November 26, 2018 cursive constructivist analysis of key British and US political spokespeople. Accepted: December 26, 2018 We argue that historically embedded values and interests stemming from un- Published: December 29, 2018 ity forged by World War Two have taken on new meanings: the AASR being Copyright © 2019 by authors and constructed by both normative and strategic cultures. The former, we argue, Scientific Research Publishing Inc. continues to forge a common alliance between the US and Britain, while the This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International latter produces notable tensions between the two states. License (CC BY 4.0). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Keywords Open Access Anglo-American, Special Relationship, Discourse, Intervention, Conflict 1. Introduction At various times in its protracted history, the Anglo-American Special Rela- tionship1 has waxed and waned in its potency since Winston Churchill’s first usage. -

The United States Government Manual 2009/2010

The United States Government Manual 2009/2010 Office of the Federal Register National Archives and Records Administration The artwork used in creating this cover are derivatives of two pieces of original artwork created by and copyrighted 2003 by Coordination/Art Director: Errol M. Beard, Artwork by: Craig S. Holmes specifically to commemorate the National Archives Building Rededication celebration held September 15-19, 2003. See Archives Store for prints of these images. VerDate Nov 24 2008 15:39 Oct 26, 2009 Jkt 217558 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6996 Sfmt 6996 M:\GOVMAN\217558\217558.000 APPS06 PsN: 217558 dkrause on GSDDPC29 with $$_JOB Revised September 15, 2009 Raymond A. Mosley, Director of the Federal Register. Adrienne C. Thomas, Acting Archivist of the United States. On the cover: This edition of The United States Government Manual marks the 75th anniversary of the National Archives and celebrates its important mission to ensure access to the essential documentation of Americans’ rights and the actions of their Government. The cover displays an image of the Rotunda and the Declaration Mural, one of the 1936 Faulkner Murals in the Rotunda at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) Building in Washington, DC. The National Archives Rotunda is the permanent home of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution of the United States, and the Bill of Rights. These three documents, known collectively as the Charters of Freeedom, have secured the the rights of the American people for more than two and a quarter centuries. In 2003, the National Archives completed a massive restoration effort that included conserving the parchment of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights, and re-encasing the documents in state-of-the-art containers. -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2014 Remarks on the Resignation Of

Administration of Barack Obama, 2014 Remarks on the Resignation of James F. "Jay" Carney as White House Press Secretary and the Appointment of Joshua R. Earnest as White House Press Secretary May 30, 2014 [The President interrupted a press briefing by Press Secretary Carney.] The President. Hello. You haven't seen me enough today. One of Jay's favorite lines is, "I have no personnel announcements at this time." But I do. And it's bittersweet. It involves one of my closest friends here in Washington. In April, Jay came to me in the Oval Office and said he was thinking about moving on, and I was not thrilled, to say the least. But Jay has had to wrestle with this decision for quite some time. He has been on my team since day one: for 2 years with the Vice President, for the past 3 ½ years as my Press Secretary. And it has obviously placed a strain on Claire, his wife, and his two wonderful kids Hugo and Della. Della's Little League team, by the way, I had a chance to see the other day, and she's a fine pitcher. But he wasn't seeing enough of the games. Jay was a reporter for 21 years before coming to the White House, including a stint as Moscow bureau chief for Time magazine during the collapse of the Soviet empire. So he comes to this place with a reporter's perspective. That's why, believe it or not, I actually think he will miss hanging out with all of you, including the guys in the front row. -

Contemporary Practice of the United States Relating to International Law Kristina Daugirdas University of Michigan Law School, [email protected]

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Articles Faculty Scholarship 2017 Contemporary Practice of the United States Relating to International Law Kristina Daugirdas University of Michigan Law School, [email protected] Julian Davis Mortenson University of Michigan Law School, [email protected] Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/1864 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles Part of the International Law Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation Daugirdas, Kristina, co-editor. "Contemporary Practice of the United States Relating to International Law." J. D. Mortenson, co-editor. Am. J. Int'l L. 111, no. 2 (2017): 476-537. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright © 2017 by The American Society of International Law CONTEMPORARY PRACTICE OF THE UNITED STATES RELATING TO INTERNATIONAL LAW EDITED BY KRISTINA DAUGIRDAS AND JULIAN DAVIS MORTENSON In this section: • United States Abstains on Security Council Resolution Criticizing Israeli Settlements • United States Sanctions Russian Individuals and Entities After Accusing Russian Government of Using Hacking to Interfere with U.S. Election Process; -

CI&E Contest Manual

CURRENT ISSUES AND EVENTS BRADLEY WILSON, PH.D. | CONTEST DIRECTOR CAPITAL CONFERENCE | 2017 Photo by Keith McDuffee Only 45 percent of Americans were able to correctly identify what the initials in GOP stood for. 55 percent of Americans believe that Christianity was written into the Constitution and that the founding fathers wanted One Nation Under Jesus When asked on what year 9/11 took place, 30 percent of Americans were unable to answer the question correctly. When looking at a map of the world, young Americans had a difficult time correctly identifying Iraq (14 percent) and Afghanistan (17 percent). ABOUT THE CONTEST • 40 objective questions • Essay (10 points) • 60 minutes • Top score individual (objective plus essay) • Top score team (objective only; top three individuals constitute team score) WHO MAY ENTER? • School may enter four students at district. • Three individuals advance from district to regional to state. • Four members of winning team advance. WHAT AREAS WILL YOU COVER? • War and conflict • Media • Politics • Crime • Health • Education • Science/technology • Environment • Economics (economy, • Awards /Honors (not deficit, unemployment) entertainment) ELEMENTS OF NEWS • Timeliness — when? • Conflict — political, ideological, cultural • Consequence — what? why is it important? • Prominence — who? • Proximity — where? how? • Oddity — unusual events that make the news • Human Interest — newsmakers in a more human role WHO QUESTION Who is Jorge Mario Bergoglio? A. Cardinal and Archbishop in New York City B. Trump fund-raiser charged with fraud and violating campaign-finance laws C. First Hispanic on the U.S. Supreme Court D. Pope Francis of Assisi WHO QUESTION Who is Jorge Mario Bergoglio? A.