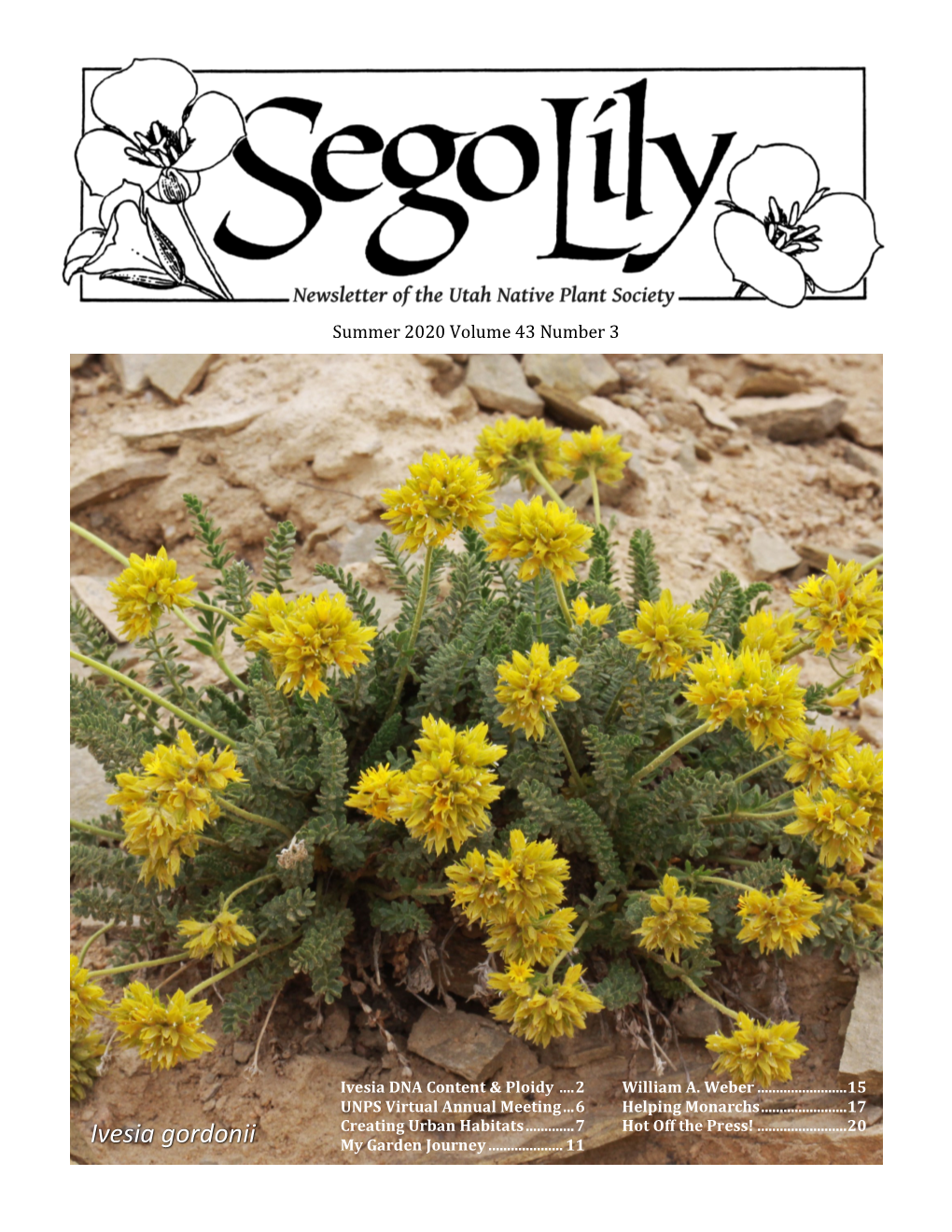

Ivesia Gordonii My Garden Journey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Field Release of the Leaf-Feeding Moth, Hypena Opulenta (Christoph)

United States Department of Field release of the leaf-feeding Agriculture moth, Hypena opulenta Marketing and Regulatory (Christoph) (Lepidoptera: Programs Noctuidae), for classical Animal and Plant Health Inspection biological control of swallow- Service worts, Vincetoxicum nigrum (L.) Moench and V. rossicum (Kleopow) Barbarich (Gentianales: Apocynaceae), in the contiguous United States. Final Environmental Assessment, August 2017 Field release of the leaf-feeding moth, Hypena opulenta (Christoph) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), for classical biological control of swallow-worts, Vincetoxicum nigrum (L.) Moench and V. rossicum (Kleopow) Barbarich (Gentianales: Apocynaceae), in the contiguous United States. Final Environmental Assessment, August 2017 Agency Contact: Colin D. Stewart, Assistant Director Pests, Pathogens, and Biocontrol Permits Plant Protection and Quarantine Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service U.S. Department of Agriculture 4700 River Rd., Unit 133 Riverdale, MD 20737 Non-Discrimination Policy The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination against its customers, employees, and applicants for employment on the bases of race, color, national origin, age, disability, sex, gender identity, religion, reprisal, and where applicable, political beliefs, marital status, familial or parental status, sexual orientation, or all or part of an individual's income is derived from any public assistance program, or protected genetic information in employment or in any program or activity conducted or funded by the Department. (Not all prohibited bases will apply to all programs and/or employment activities.) To File an Employment Complaint If you wish to file an employment complaint, you must contact your agency's EEO Counselor (PDF) within 45 days of the date of the alleged discriminatory act, event, or in the case of a personnel action. -

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

Region 4 Threatened, Endangered and Sensitive Species List

INTERMOUNTAIN REGION (R4) THREATENED, ENDANGERED, PROPOSED, AND, SENSITIVE SPECIES June 2016 KNOWN / SUSPECTED DISTRIBUTION BY FOREST STATUS FOREST ENDANGERED ASH BOI B-T CAR CHA DIX FIS HUM M-L PAY SAL SAW TAR TOI UIN W-C MAMMALS Black-footed ferret 3/11/67 o o Mustela nigripes Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep Ovis canadensis X sierra January 3, 2000 BIRDS Southwestern willow flycatcher 2/27/95 X ? Empidonax traillii extimus ED 3/29/95 Whooping crane 3/11/67 X ? Grus americana REPTILES AND AMPHIBIANS Sierra Nevada Yellow-legged Frog 06/30/2014 X Rana sierrae INSECTS Mt. Charleston Blue Butterfly 10/21/2013 X Icaricia shasta charlestonensis FISH June sucker 3/31/86 o o Chasmistes liorus Bonytail chub 4/23/80 o o o o o o o Gila elegans Humpback chub 3/11/67 o o o o o o o Gila cypha Colorado pike minnow 3/11/67 o o o o o o o Ptychocheilus lucius Kendall Warm Springs dace 10/13/70 X Rhinichthys osculus Proposed, Endangered, Threatened, and Sensitive Species List, R4 Page 2 of 19 ENDANGERED ASH BOI B-T CAR CHA DIX FIS HUM M-L PAY SAL SAW TAR TOI UIN W-C Sockeye salmon, (Snake River0 11/20/91 + + + X Oncorhynchus nerka (CH 12/28/98) Razorback sucker 10/23/91 o o o o o o o Xyrauchen texanus (ED 11/22/91) Sturgeon, pallid o Scaphirhynchus albus PLANTS San Rafael cactus X Pediocactus despainii Clay phacelia 09/28/78 ? X Phacelia argillacea THREATENED ASH BOI B-T CAR CHA DIX FIS HUM M-L PAY SAL SAW TAR TOI UIN W-C MAMMALS Canada lynx 4/15/00 X X X X X X ? ? Lynx canadensis Grizzly bear 9/21/2009 X X Ursus arctos horribilis Gray wolf (Wyoming Rocky -

Identification of Milkweeds (Asclepias, Family Apocynaceae) in Texas

Identification of Milkweeds (Asclepias, Family Apocynaceae) in Texas Texas milkweed (Asclepias texana), courtesy Bill Carr Compiled by Jason Singhurst and Ben Hutchins [email protected] [email protected] Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Austin, Texas and Walter C. Holmes [email protected] Department of Biology Baylor University Waco, Texas Identification of Milkweeds (Asclepias, Family Apocynaceae) in Texas Created in partnership with the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center Design and layout by Elishea Smith Compiled by Jason Singhurst and Ben Hutchins [email protected] [email protected] Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Austin, Texas and Walter C. Holmes [email protected] Department of Biology Baylor University Waco, Texas Introduction This document has been produced to serve as a quick guide to the identification of milkweeds (Asclepias spp.) in Texas. For the species listed in Table 1 below, basic information such as range (in this case county distribution), habitat, and key identification characteristics accompany a photograph of each species. This information comes from a variety of sources that includes the Manual of the Vascular Flora of Texas, Biota of North America Project, knowledge of the authors, and various other publications (cited in the text). All photographs are used with permission and are fully credited to the copyright holder and/or originator. Other items, but in particular scientific publications, traditionally do not require permissions, but only citations to the author(s) if used for scientific and/or nonprofit purposes. Names, both common and scientific, follow those in USDA NRCS (2015). When identifying milkweeds in the field, attention should be focused on the distinguishing characteristics listed for each species. -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

Crested Butte Wildflower Guide

LUPINE, SILVERY Wildflowers Shrubs Lupinus argenteus C C D D S S GOLDENEYE, SHOWY GOLDENWEED, SNEEZEWEED, ORANGE LOVAGE, PORTER'S ELEPHANTELLA FITWEED, CASE'S ROSE, WILD SNOWBERRY CINQUEFOIL, SHRUBBY HOLLY GRAPE Heliomeris multiflora CURLYHEAD Hymenoxys hoopesii OR OSHA ELEPHANT'S HEAD Corydalis caseana brandegei Rosa woodsii Symphoricarpos Potentilla fructicosa Mahonia repens Contributors Pyrrocoma crocea Ligusticum porteri Pedicularis groenlandica rotundifulius Vincent Rossignol The Handy Dandy ■ BS Landscape Architecture Kansas State University 1965 Wildflower Guide C C D S S S ■ Gunnison County resident since 1977 ■ Crested Bue Wildflower Fesval Tour leader from A PHOTO GUIDE TO POPULAR 19912002 WILDFLOWERS AND SHRUBS BLOOMING ■ Field Biologist Plants: US Forest Service and Bureau of IN AND NEAR CRESTED BUTTE Land Management; Gunnison, Colorado. Summer Seasonal: 19952011 Rick Reavis Wildflower Fesval Board Member The Crested Bue Wildflower Fesval is Rick has been exploring and idenfying nave and dedicated to the conservaon, preservaon and introduced plants around the Crested Bue area since appreciaon of wildflowers through educaon 1984. Rick is a 27year former business owner of an award and celebraon. We are commied to winning landscape development company. As an Associate protecng our natural botanical heritage for ARNICA, HEARTLEAF LILY, GLACIER OR SNOW SUNFLOWER, MULE'S EARS LUPINE, SILVERY LARKSPUR, DWARF MONKSHOOD ELDERBERRY, RED KINNIKINNIK HONEYSUCKLE, WILLOW, YELLOW Professor at Oklahoma State University, Oklahoma City, he future generaons and promong sound Arnica cordifolia Erythronium grandiflorum Wyethia amplexicaulis Lupinus argenteus Delphinium nuttallianum Aconitum columbianum Sambucus racemosa Arctostaphylos uva-ursi TWINBERRY Salix lutea spent several years teaching classes in plant idenficaon, stewardship of this priceless resource. Lonicera involucrata landscape maintenance and general horculture. -

Danaus Plexippus)

1. Species: Monarch (butterfly) (Danaus plexippus) 2. Status: Table 1 summarizes the current status of this species or subspecies by various ranking entity and defines the meaning of the status. Table 1. Current status of Danaus plexippus. Entity Status Status Definition NatureServe G4 Species is Apparently Secure At fairly low risk of extinction or elimination due to an extensive range and/or many populations or occurrences, but with possible cause for some concern as a result of local recent declines, threats, or other factors. CNHP S5 Species is Secure At very low risk or extinction or elimination due to a very extensive range, abundant populations or occurrences, and little to no concern from declines or threats. Colorado None N/A State List Status USDA Forest R2 Sensitive Region 2 Regional Forester’s Sensitive Species Service USDI FWSb None N/A a Colorado Natural Heritage Program. b US Department of Interior Fish and Wildlife Service. The 2012 U.S. Forest Service Planning Rule defines Species of Conservation Concern (SCC) as “a species, other than federally recognized threatened, endangered, proposed, or candidate species, that is known to occur in the plan area and for which the regional forester has determined that the best available scientific information indicates substantial concern about the species' capability to persist over the long-term in the plan area” (36 CFR 219.9). This overview was developed to summarize information relating to this species’ consideration to be listed as a SCC on the Rio Grande National Forest, and to aid in the development of plan components and monitoring objectives. -

2017 RISE Symposium Abstract Book

RISE SPONSORED STUDENT SUMMER SYMPOSIUM Thursday August 24, 2017 Research Presenters: RISE, McNair, LSAMP Student Researchers Time: 8:30AM-3:30PM (Lunch Provided) Location: Bldg 4-2-314 (Conference Room) Presentation Schedule Introduction by Dr. Jill Adler Moderator: Dr. Jill Adler Time Name Presentation Title 8:30AM Tim Batz Morphological and developmental studies of the shoot apical meristem in Aquilegia coerulea 8:45 Uriah Sanders Analysis of gene expression in developing shoot apical meristems of Aquilegia coerulea 9:00 Summer Blanco Techniques to Understand Floral Organ Abscission in Delphinium Species 9:15 Sierra Lauman Restoration of invaded walnut woodlands using a trait-based community assembly approach 9:30 Eddie Banuelos Assessment of Titanium-based prosthetic alloy colonization by Staphylococcus epidermidis & Pseudomonas aeruginosa 9:45 Jacqueline Transformation efficiency and the effects of ampicillin on bacterial Gutierrez growth 10:00 Break Moderator: Dr. Nancy Buckley 10:15 Marie Gomez Building a quantitative model for studying the effect of antibiotics that inhibit protein translation in live cells 10:30 Taylor Halsey Monitoring changing levels of ghrelin and calcium using silica- encapsulated mammalian cells 10:45 Isis Janilkarn-Urena Comparing the effect of garlic and allicin between J774A.1 and RAW 264.7 murine macrophages in response to LPS and Heat Killed Candida albicans 11:00 Jacqueline Lara Small Cell Lung Cancer: the use of Aurora Kinase inhibitors and BCL2 inhibitors as alternative therapeutics 11:15 Jade Lolarga Validation of overexpression and knockdown of Twist1 in breast cancer cells 11:30 Ben Soto Construction of clinically relevant mutations in Ten-eleven translocation methylcytosine dioxygenase 2 (TET2) 11:45 Lunch Moderator: Dr. -

Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Fort Bowie National Historic Site Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Fort Bowie National Historic Site

Powell, Schmidt, Halvorson In Cooperation with the University of Arizona, School of Natural Resources Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Fort Bowie National Historic Site Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Fort Bowie National Historic Site Plant and Vertebrate Vascular U.S. Geological Survey Southwest Biological Science Center 2255 N. Gemini Drive Flagstaff, AZ 86001 Open-File Report 2005-1167 Southwest Biological Science Center Open-File Report 2005-1167 February 2007 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey National Park Service In cooperation with the University of Arizona, School of Natural Resources Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Fort Bowie National Historic Site By Brian F. Powell, Cecilia A. Schmidt , and William L. Halvorson Open-File Report 2005-1167 December 2006 USGS Southwest Biological Science Center Sonoran Desert Research Station University of Arizona U.S. Department of the Interior School of Natural Resources U.S. Geological Survey 125 Biological Sciences East National Park Service Tucson, Arizona 85721 U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2006 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS-the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web:http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Suggested Citation Powell, B. F, C. A. Schmidt, and W. L. Halvorson. 2006. Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Fort Bowie National Historic Site. -

Tidal Marsh Recovery Plan Habitat Creation Or Enhancement Project Within 5 Miles of OAK

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Recovery Plan for Tidal Marsh Ecosystems of Northern and Central California California clapper rail Suaeda californica Cirsium hydrophilum Chloropyron molle Salt marsh harvest mouse (Rallus longirostris (California sea-blite) var. hydrophilum ssp. molle (Reithrodontomys obsoletus) (Suisun thistle) (soft bird’s-beak) raviventris) Volume II Appendices Tidal marsh at China Camp State Park. VII. APPENDICES Appendix A Species referred to in this recovery plan……………....…………………….3 Appendix B Recovery Priority Ranking System for Endangered and Threatened Species..........................................................................................................11 Appendix C Species of Concern or Regional Conservation Significance in Tidal Marsh Ecosystems of Northern and Central California….......................................13 Appendix D Agencies, organizations, and websites involved with tidal marsh Recovery.................................................................................................... 189 Appendix E Environmental contaminants in San Francisco Bay...................................193 Appendix F Population Persistence Modeling for Recovery Plan for Tidal Marsh Ecosystems of Northern and Central California with Intial Application to California clapper rail …............................................................................209 Appendix G Glossary……………......................................................................………229 Appendix H Summary of Major Public Comments and Service -

National Wetlands Inventory Map Report for Quinault Indian Nation

National Wetlands Inventory Map Report for Quinault Indian Nation Project ID(s): R01Y19P01: Quinault Indian Nation, fiscal year 2019 Project area The project area (Figure 1) is restricted to the Quinault Indian Nation, bounded by Grays Harbor Co. Jefferson Co. and the Olympic National Park. Appendix A: USGS 7.5-minute Quadrangles: Queets, Salmon River West, Salmon River East, Matheny Ridge, Tunnel Island, O’Took Prairie, Thimble Mountain, Lake Quinault West, Lake Quinault East, Taholah, Shale Slough, Macafee Hill, Stevens Creek, Moclips, Carlisle. • < 0. Figure 1. QIN NWI+ 2019 project area (red outline). Source Imagery: Citation: For all quads listed above: See Appendix A Citation Information: Originator: USDA-FSA-APFO Aerial Photography Field Office Publication Date: 2017 Publication place: Salt Lake City, Utah Title: Digital Orthoimagery Series of Washington Geospatial_Data_Presentation_Form: raster digital data Other_Citation_Details: 1-meter and 1-foot, Natural Color and NIR-False Color Collateral Data: . USGS 1:24,000 topographic quadrangles . USGS – NHD – National Hydrography Dataset . USGS Topographic maps, 2013 . QIN LiDAR DEM (3 meter) and synthetic stream layer, 2015 . Previous National Wetlands Inventories for the project area . Soil Surveys, All Hydric Soils: Weyerhaeuser soil survey 1976, NRCS soil survey 2013 . QIN WET tables, field photos, and site descriptions, 2016 to 2019, Janice Martin, and Greg Eide Inventory Method: Wetland identification and interpretation was done “heads-up” using ArcMap versions 10.6.1. US Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) National Wetlands Inventory (NWI) mapping contractors in Portland, Oregon completed the original aerial photo interpretation and wetland mapping. Primary authors: Nicholas Jones of SWCA Environmental Consulting. 100% Quality Control (QC) during the NWI mapping was provided by Michael Holscher of SWCA Environmental Consulting. -

Understanding the Floral Transititon in Aquilegia Coerulea And

UNDERSTANDING THE FLORAL TRANSITION IN AQUILEGIA COERULEA AND DEVELOPMENT OF A TISSUE CULTURE PROTOCOL A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State Polytechnic University, Pomona In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science In Plant Science By Timothy A. Batz 2018 SIGNATURE PAGE THESIS: UNDERSTANDING THE FLORAL TRANSITION IN AQUILEGIA COERULEA AND DEVELOPMENT OF A TISSUE CULTURE PROTOCOL AUTHOR: Timothy A. Batz DATE SUBMITTED: Summer 2018 College of Agriculture Dr. Bharti Sharma Thesis Committee Co-Chair Department of Biological Sciences Dr. Valerie Mellano Thesis Committee Co-Chair Plant Science Department Dr. Kristin Bozak Department of Biological Sciences ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the many faculty, family, and friends who helped me enormously throughout my master’s program. The endless support, mentorship, and motivation was crucial to my success now and in the future. Thank you! Dr. Mellano, as my academic advisor and mentor since my freshman year at Cal Poly Pomona, I greatly appreciate your time and dedication to my success. Thank you for guiding me towards my career in science. Dr. Sharma, thank you for taking me into your lab and taking the role of research mentor. Your letters of support allowed me the opportunities to grow as a scientist. Dr. Bozak, I always had a pleasure meeting with you for advice and constructive critiques. Thank you for the time spent reading my statements and the opportunities to gain presentation skills by lecturing in your classes. Dr. Still, thank you for introducing me into the world of research. Thank you for helping me understand the work and input required for scientific success.