Title Spectres of Shakespeare: Ong Keng Sen's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996 Stage by Stage The Development of the National Theatre from 1848 Designed by Michael Mayhew Compiled by Lyn Haill & Stephen Wood With thanks to Richard Mangan and The Mander & Mitchenson Theatre Collection, Monica Sollash and The Theatre Museum The majority of the photographs in the exhibition were commissioned by the National Theatre and are part of its archive The exhibition was funded by The Royal National Theatre Foundation Richard Eyre. Photograph by John Haynes. 1988 To mark the company’s 25th birthday in Peter Hall’s last year as Director of the National October, The Queen approves the title ‘Royal’ Theatre. He stages three late Shakespeare for the National Theatre, and attends an plays (The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale, and anniversary gala in the Olivier. Cymbeline) in the Cottesloe then in the Olivier, and leaves to start his own company in the The funds raised are to set up a National West End. Theatre Endowment Fund. Lord Rayne retires as Chairman of the Board and is succeeded ‘This building in solid concrete will be here by the Lady Soames, daughter of Winston for ever and ever, whatever successive Churchill. governments can do to muck it up. The place exists as a necessary part of the cultural scene Prince Charles, in a TV documentary on of this country.’ Peter Hall architecture, describes the National as ‘a way of building a nuclear power station in the September: Richard Eyre takes over as Director middle of London without anyone objecting’. of the National. 1989 Alan Bennett’s Single Spies, consisting of two A series of co-productions with regional short plays, contains the first representation on companies begins with Tony Harrison’s version the British stage of a living monarch, in a scene of Molière’s The Misanthrope, presented with in which Sir Anthony Blunt has a discussion Bristol Old Vic and directed by its artistic with ‘HMQ’. -

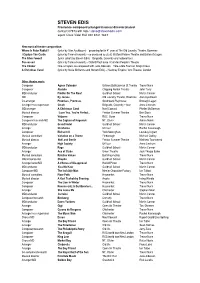

STEVEN EDIS Freelance Composer/Arranger/Musical Director/Pianist Contact 07973 691168 / [email protected] Agent Clare Vidal Hall 020 8741 7647

STEVEN EDIS Freelance composer/arranger/musical director/pianist contact 07973 691168 / [email protected] agent Clare Vidal Hall 020 8741 7647 New musical theatre composition: Where Is Peter Rabbit? (lyrics by Alan Ayckbourn) – preparing for its 4 th year at The Old Laundry Theatre, Bowness I Capture The Castle (lyrics by Teresa Howard) – co-produced by (& at) Watford Palace Theatre and Bolton Octagon The Silver Sword (lyrics (also!) by Steven Edis) – Belgrade, Coventry and national tour Possessed (lyrics by Teresa Howard) – Oxford Playhouse / Camden People's Theatre The Choker One-act opera co-composed with Jude Alderson – Tête-a-tête Festival. King's Cross A Christmas Carol (lyrics by Susie McKenna and Steven Edis) – Hackney Empire / Arts Theatre, London Other theatre work: Composer Agnes Colander Ustinov,Bath/Jermyn St Theatre Trevor Nunn Composer Aladdin Chipping Norton Theatre John Terry MD/conductor Fiddler On The Roof Guildhall School Martin Connor MD By Jeeves Old Laundry Theatre, Bowness Alan Ayckbourn Co-arranger Promises, Promises Southwark Playhouse Bronagh Lagan Arranger/mus.supervisor Crush Belgrade, Coventry + tour Anna Linstrum MD/arranger A Christmas Carol Noel Coward Phelim McDermott Musical director I Love You, You're Perfect... Frinton Summer Theatre Ben Stock Composer Volpone RSC, Swan Trevor Nunn Composer/research/MD The Captain of Köpenick NT, Olivier Adrain Noble MD/conductor Grand Hotel Guildhall School Martin Connor Arranger Oklahoma UK tour Rachel Kavanaugh Composer Richard III York/Nottingham Loveday Ingram -

Voice Training and the Royal National Theatre Rena Cook

Spring 1999 165 Voice Training and the Royal National Theatre Rena Cook I stepped off the double-decker bus at Waterloo Station with my map in hand, walked several blocks and found the Old Vic quite easily. But the Royal National Theatre Studio, where the orientation was to take place, was nowhere in sight. "Next to the Old Vic," I had been told. With address and directions in my pocket, I surveyed the area as my internal compass spun out of control. After a brief moment of panic, I went to the box office and asked for help. "Out this door, two steps to your left and through the iron gate." I had traveled to London to participate in a course entitled "International Voice Intensive" with Patsy Rodenburg. As I walked up the steps of the studio on that chilly Sunday afternoon, with jet lag hanging heavily on my limbs, I had little idea that in my two weeks study I was about to experience a Zeitgeist of contemporary London theatre, training and practice. The focus was, of course, the voice work under the tutelage of master teacher Patsy Rodenburg, who currently heads the voice departments at the Royal National Theatre and Guildhall School of Music and Drama. In addition, the course participants were exposed to and interacted with some of the finest artists working in Western theatre today, including Trevor Nunn, Richard Eyre, and Judi Dench. Following each exhaustive day of study, workshop, and discussion, we attended theatre, viewing five of the six productions currently in repertory at the National. -

Tesori Di Svezia E Danimarca

Capo Nord Alta ALF Lofoten ISLANDA Reykjavik KEF Tesori di Svezia 7 GIORNI / 6 NOTTI TOUR DI GRUPPO CON GUIDA e Danimarca DI LINGUA ITALIANA Un tour fiabescoFINLANDIA tra foreste, laghi e castelli Castello di Frederiksborg Nusnäs Falun Uppsala Karlstad Stoccolma ARN ESTONIA Göteborg SVEZIA DANIMARCA LETTONIA Copenaghen CPH Stoccolma Uppsala GIORNO 1 - ITALIA / STOCCOLMA e villaggi come Fjällbacka, con le sue pittoresche stradine. Arrivo a Stoccolma. Trasferimenti non inclusi, disponibili Il paesaggio è caratterizzato da un’atmosfera idilliaca, uno IN EVIDENZA su supplemento. Incontro con accompagnatore in hotel stile di vita tranquillo che segue l’antica tradizione svedese, Informiamo che per ragioni logistiche e tecniche, (disponibile entro le ore 21:00) Benvenuto a Stoccolma, dove le principali attivitá sono legate al mare (pesca di ara- l’itinerario puó subire delle variazioni nell’ordine la regina delle Capitali del Nord! In base al Vostro orario goste, conattaggio e kajak), Pranzo libero lungo il percorso. delle visite e potrebbe anche essere effettuato in senso inverso. Qualsiasi modifica apportata di arrivo, consigliamo una passeggiata per scoprire Dal villaggio di Lysekil ci imbarcheremo per una navigazio- da V.O.S non altererá in alcun modo la quantitá/ questa città dal fascino unico, ne di un´ora e mezza attraverso l’arcipelago per scoprire la qualitá dei servizi inclusi in programma. magnifica natura e le colonie di foche adagiate sulle rocce. Pernottamento presso Clarion Amaranten o similare INCLUSO NEL PREZZO Proseguimento verso Göteborg, una delle città portuali più importanti della Svezia. Consigliamo una passeggiata • Volo a/r Roma e/o Milano GIORNO 2 - STOCCOLMA / UPPSALA - FALUN • 6 pernottamenti con colazione negli Colazione in hotel. -

Introduction: Shakespeare in Cross-Cultural Spaces

Multicultural Shakespeare: Translation, Appropriation and Performance vol. 15 (30), 2016; DOI: 10.1515/mstap-2017-0001 Robert Sawyer and Varsha Panjwani Introduction: Shakespeare in Cross-Cultural Spaces The seeds for this volume were planted in the fertile soil of Guimarães, Portugal, during a colloquium organized by Francesca Rayner and the Centre for Humanistic Studies of the Universidade do Minho in October 2015, where scholars presented papers on the subject of “Shakespearean Collaborations.” Two themes emerged across many of the papers: the intercultural negotiation through Shakespeare and the consideration of spatial studies of Shakespeare. These ideas, germinated in Portugal, were then cross-pollinated with similar topics by other multinational Shakespearean scholars for this special issue on “Shakespeare in Cross-Cultural Spaces.” As we worked on this issue through 2016, the significance of discussing our first theme of cross-cultural relations became increasingly urgent. While, on the one hand, the world was marking the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, on the other hand, political and cultural borders were being re-imagined and re-made: the United Kingdom voted to exit from the European Union, the mass-migration of refugees from war-torn countries such as Iraq, Syria and Libya continued to increase, and the U.S. president, Donald Trump, threatened to build a wall across the Mexican border during his campaign. It seemed that the currents of Shakespeare studies and performance, which were celebrating diversity and interculturalism as witnessed by publications such as Shakespeare, Race and Performance: The Diverse Bard (2016) and productions such as Royal Shakespeare Company’s Hamlet with the Black actor, Paapa Essiedu, in the lead role (both reviewed in this issue), were moving in the opposite direction to these international events. -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85054-4 - The Cambridge Companion to David Hare Edited by Richard Boon Frontmatter More information the cambridge companion to david hare David Hare is one of the most important playwrights to have emerged in the UK in the last forty years. This volume examines his stage plays, television plays and cinematic films, and is the first book of its kind to offer such comprehen- sive and up-to-date critical treatment. Contributions from leading academics in the study of modern British theatre sit alongside those from practitioners who have worked closely with Hare throughout his career, including former Director of the National Theatre Sir Richard Eyre. Uniquely, the volume also includes a chapter on Hare’s work as journalist and public speaker; a personal mem- oir by Tony Bicat,ˆ co-founder with Hare of the enormously influential Portable Theatre; and an interview with Hare himself in which he offers a personal ret- rospective of his career as a film maker which is his fullest and clearest account of that work to date. A complete list of books in the series is at the back of this book. © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85054-4 - The Cambridge Companion to David Hare Edited by Richard Boon Frontmatter More information THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO DAVID HARE EDITED BY RICHARD BOON University of Hull © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85054-4 - The Cambridge Companion to David Hare Edited by Richard Boon Frontmatter More information cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao˜ Paulo, Delhi Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 8ru,UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521615570 C Cambridge University Press 2007 This publication is in copyright. -

Sovereign Order of St. John of Jerusalem, Knights Hospitaller

Sovereign Order of St. John of Jerusalem, Knights Hospitaller TOUR OPTION 1 WEDNESDAY, 17 JUNE 2020 17:00 (5PM) sharp! MEET IN THE HOTEL LOBBY FOR A TOUR OF COPENHAGEN’S LATIN QUARTER & A NO-HOST DINNER. YOUR GUIDE WILL BE OUR VERY OWN COMMANDER JENS A. VEXO. WHEELCHAIR ACCESSIBLE Latinerkvarteret Stylish Latinerkvarteret, or the Latin Quarter, is known for charming, colorful buildings on Mejlgade street, including the 17th- century Juul’s House. Buzzing Pustervig Square is home to global eateries and hip cafes serving traditional smørrebrød open- faced sandwiches. Cultural venues include East of Eden, a tiny cinema showing foreign and indie films, and the Women’s Museum, telling 150 years of women’s stories. The neighborhood dates back to the 1200’s, with the founding of a Latin school (hence the name), and later, the University of Copenhagen was created here in the 1400’s, lending an air of intellectual vibrancy to the narrow streets lined with medieval buildings. And while it’s an ideal place for visitors to base themselves during a visit to the Denmark’s largest city, it’s also convenient. From here, some of the best drinking, eating and sites in the city are all about a ten-minute walk away, in neighborhoods like Vesterbro and Indre By (the city center). We will visit… Rosenborg Castle Far more intimate than Europe’s usual imperial palaces, the turreted 17th-century Rosenborg Castle has three cozy floors with gilded chambers, chinoiserie, and intricate tapestries. In warm months, pick up lunch to go from the nearby smørrebrød shop Aamanns and go for a picnic on the lush grounds. -

Charlotte Sutton Casting CV 2019

charlotte sutton cdg AGENT: Rachael Swanston, Conway van Gelder Grant 0207 287 0077/ [email protected] AS CASTING DIRECTOR: 2019 Fairview Young Vic Nadia Latif 2019 Death of a Salesman Young Vic & Piccadilly Marianne Elliott & Miranda Cromwell 2019 The Butterfly Lion Chichester Festival Dale Rooks 2019 Sing Yer Heart Out for the Lads Chichester Festival Nicole Charles 2019 Hedda Tesman Chichester Festival Holly Race Roughan 2019 8 Hotels Chichester Festival Richard Eyre 2019 Oklahoma! Chichester Festival Jeremy Sams 2019 The Deep Blue Sea Chichester Festival Paul Foster 2019 The Light in the Piazza Royal Festival Hall &LA Daniel Evans 2019 Plenty Chichester Festival Kate Hewitt 2019 Shadowlands Chichester Festival Rachel Kavanaugh 2019 This is My Family Chichester Festival Daniel Evans 2019 Wild East Young Vic Lekan Lawal 2018 The Convert Young Vic Ola Ince 2018 Caroline, or Change Playhouse&Hampstead Michael Longhurst 2018 The Watsons Chichester Festival Samuel West 2018 My England Young Vic (digital) Nadia Latif/ Rodney Charles 2018 Company* Gielgud Marianne Elliott 2018 Cock Chichester Festival Kate Hewitt 2018 Flowers for Mrs Harris Chichester Festival Daniel Evans 2018 Copenhagen Chichester Festival Michael Blakemore 2018 Me and My Girl Chichester Festival Daniel Evans 2018 The Meeting Chichester Festival Natalie Abrahami 2018 The Chalk Garden Chichester Festival Alan Strachan 2018 Present Laughter Chichester Festival Sean Foley 2018 random/generations Chichester Festival Tinuke Craig 2018 Humble Boy Orange Tree Theatre Paul -

Maggie Service

Maggie Service Nominated for 2012 Manchester Theatre Award for Best Supporting Actress for THE COUNTRY WIFE. Agents Jess Alford Associate Agent [email protected] Ellie Blackford [email protected] 020 3214 0800 Roles Film Production Character Director Company HALCYON HEIGHTS Chirpy Cheryl. Isla Ure Fiddy West productions LONDON ROAD Evening Star Girl Rufus Norris BBC Films Television Production Character Director Company QUIZ Kerry 'The Floor Stephen Frears Left Bank Pictures for ITV & Manager' AMC LIFE Sarah Jane Pollard & Iain Drama Republic for BBC 1 Forsyth GOOD OMENS Sister Theresa Douglas Mackinnon BBC/Amazon Garrulous MAN DOWN Jenny Al Campbell Channel 4 W1A Hotel Receptionist John Morton BBC THREE GIRLS Caroline Wallace Philippa Lowthorpe BBC RED DWARF XI Professor Rachel Barker Doug Naylor Baby Cow Productions for Dave United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Character Director Company QUACKS Sally Andy de Emmony Lucky Giant for NBC & BBC ALIENS Celine Jonathan van Tulleken Quite Funny Films Ltd for E4 I WANT MY WIFE Lin Paul Norton Walker Mainstreet Pictures Ltd for BACK BBC CALL THE MIDWIFE Norma Dominic Leclerc BBC 1 THE MIMIC Community Support Kieron Hawkes Running Bare Pictures for Officer Channel 4 DOCTOR WHO Elsie Ben Wheatley BBC 1 MIRANDA Georgina Juliet May BBC FOYLE'S WAR Sylvie Johnstone Stuart Orme ITV Stage Production Character Director Company DEATH OF A SALESMAN The Woman/Jenny Marianne Elliott -

The Lehman Trilogy

Park Avenue Armory, in collaboration with the National Theatre and Neal Street Productions, brings The Lehman Trilogy, by Stefano Massini, adapted by Ben Power, and directed by Sam Mendes to the Wade Thompson Dill Hall, following a sold-out run at the National Theatre Master actors Adam Godley, Ben Miles, and Simon Russell Beale will reprise their critically- acclaimed roles March 22 – April 20, 2019 Simon Russell Beale, Ben Miles and Adam Godley in The Lehman Trilogy at the National Theatre. Photo by Mark Douet. New York, NY – September 12, 2018 – In March 2019, Park Avenue Armory – in collaboration with the National Theatre and Neal Street Productions – will present the North American premiere of The Lehman Trilogy. Told in three parts in a single evening, the production will unfold in the 1 soaring 55,000-square-foot Wade Thompson Drill Hall from March 22 through April 20, 2019 in a strictly limited engagement. Directed by Sam Mendes, The Lehman Trilogy weaves through nearly two centuries of Lehman lineage, following the brothers Henry, Emanuel, and Mayer Lehman from their 1844 arrival in New York City to the 2008 collapse of the financial firm bearing their name. Adam Godley, Ben Miles, and Simon Russell Beale play the Lehman brothers, and a cast of characters including their sons and grandsons. As the inaugural production of the 2019 season, The Lehman Trilogy builds on the Armory’s history of presenting bold and engaging theater productions that explore the unexpected possibilities of the cross-genre cultural institution. The world premiere of Stefano Massini’s The Lehman Trilogy opened at the Piccolo Teatro in Milan in 2015. -

Laura-Michelle Kelly

Paddock Suite, The Courtyard, 55 Charterhouse Street, London, EC1M 6HA p: + 44 (0) 20 73360351 e: [email protected] Phone: + 44 (0) 20 73360351 Email: [email protected] Laura-Michelle Kelly Photo: Paul Smith Location: London Other: Equity Height: 5'5" (165cm) Eye Colour: Grey-Green Weight: 8st. 6lb. (54kg) Hair Colour: Black Playing Age: 16 - 30 years Hair Length: Long Appearance: Eastern European, Mediterranean,Voice Quality: Melodious White Stage 2012, Stage, Paula Ray, The Second Mrs Tanqueray, Kingston Rose Theatre, Stephen Unwin 2008, Stage, Karen, Speed The Plow, Old Vic Company, Matthew Warchus Musical 2014, Musical, Sylvis Llewelyn Davies, Finding Neverland, A.R.T Loeb Drama Center, Diane Paulus 2013, Musical, Eliza Doolittle, My Fair Lady, Kennedy Centre Washington DC, Marica Milgrim Dodge 2013, Musical, Nellie Forbrush, South Pacific, MUNY, St Louis, Rob Ruggiero 2012, Musical, Anna, The King & I, St Louis MUNY, Rob Ruggiero 2010, Musical, Mary Poppins, Mary Poppins, New Amsterdam Theatre, Richard Eyre 2004, Musical, Hodel, Fiddler On The Roof, Minskoff Theatre, Broadway, David Leveaux 2005, Musical, Emma, A Twist Of Fate, Singapore Esplanade Theatre 2005, Musical, Mary Poppins, Mary Poppins, London Prince Edward Theatre, Richard Eyre 2003, Musical, Eliza, My Fair Lady, Cameron Mackintosh Productions, Trevor Nunn 2002, Musical, Sophie, Mamma Mia, Littlestar Productions, Peter Addis 2002, Musical, Soloist, Night Of A Thousand Voices, Albert Hall 2002, Musical, Lolita, Zorro, The Old Vic, London, Chris Wrenshaw 2001, Musical, Principal, -

Linguaculture 1, 2014

LINGUACULTURE 1, 2014 THE HOLLOW CROWN:SHAKESPEARE, THE BBC, AND THE 2012 LONDON OLYMPICS RUTH M ORSE Université-Paris-Diderot Abstract During the summer of 2012, and to coincide with the Olympics, BBC2 broadcast a series called The Hollow Crown, an adaptation of Shakespeare’s second tetralogy of English history plays. The BBC commission was conceived as part of the Cultural Olympiad which accompanied Britain’s successful hosting of the Games that summer. I discuss the financial, technical, aesthetic, and political choices made by the production team, not only in the context of the Coalition government (and its attacks on the BBC) but also in the light of theatrical and film tradition. I argue that the inclusion or exclusion of two key scenes suggest something more complex and balanced that the usual nationalism of the plays'; rather, the four nations are contextualised to comprehend and acknowledge the regions – apropos not only in the Olympic year, but in 2014's referendum on the Union of the crowns of England/Wales and Scotland. Keywords: Shakespeare, BBC, adaptation, politics, Britishness During the summer of 2012, to coincide with the London summer Olympics, BBC2 broadcast a series called The Hollow Crown, an adaptation of Shakespeare’s second tetralogy of English history plays. An additional series, Shakespeare Unlocked, accompanied each play with a program fronted by a lead actor discussing the play and the process, illustrated by clips from the plays in which they had appeared (“The Hollow Crown”). The producer was the Neal Street Production Company in the person of Sam Mendes, a well-known stage and cinema director, celebrated not least for an Oscar for American Beauty, a rare honour for a first-time film director.