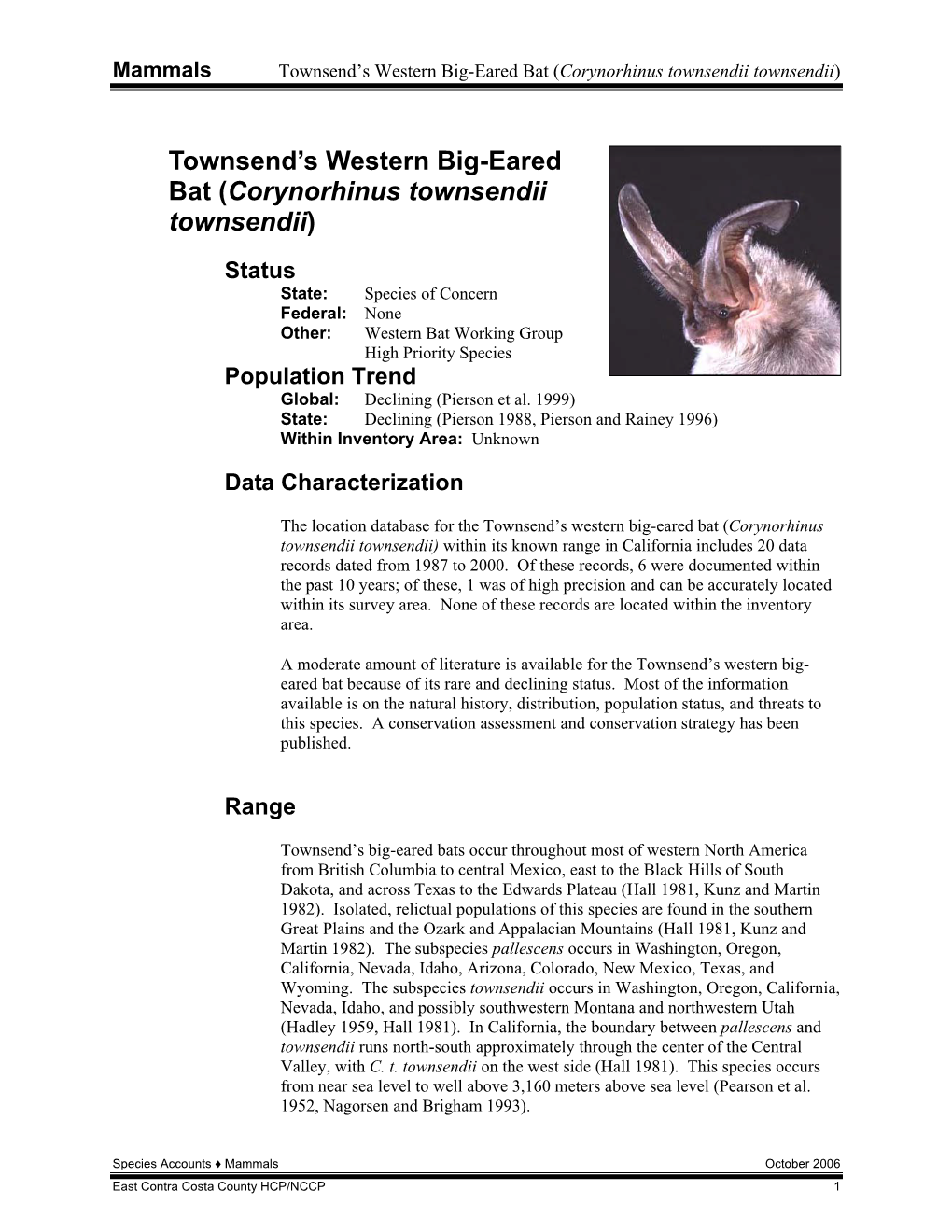

Townsend's Western Big-Eared Bat (Corynorhinus Townsendii Townsendii)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

33245 02 Inside Front Cover

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by KnowledgeBank at OSU 186 BATS OF RAVENNA VOL. 106 Bats of Ravenna Training and Logistics Site, Portage and Trumbull Counties, Ohio1 VIRGIL BRACK, JR.2 AND JASON A. DUFFEY, Center for North American Bat Research and Conservation, Department of Ecology and Organismal Biology, Indiana State University, Terre Haute, IN 47089; Environmental Solutions & Innovations, Inc., 781 Neeb Road, Cincinnati, OH 45233 ABSTRACT. Six species of bats (n = 272) were caught at Ravenna Training and Logistics Site during summer 2004: 122 big brown bats (Eptesicus fuscus), 100 little brown myotis (Myotis lucifugus), 26 red bats (Lasiurus borealis), 19 northern myotis (Myotis septentrionalis), three hoary bats (Lasiurus cinereus), and two eastern pipistrelles (Pipistrellus subflavus). Catch was 9.7 bats/net site (SD = 10.2) and 2.4 bats/net night (SD = 2.6). No bats were captured at two net sites and only one bat was caught at one site; the largest captures were 33, 36, and 37 individuals. Five of six species were caught at two sites, 2.7 (SD = 1.4) species were caught per net site, and MacArthur’s diversity index was 2.88. Evidence of reproduction was obtained for all species. Chi-square tests indicated no difference in catch of males and reproductive females in any species or all species combined. Evidence was found of two maternity colonies each of big brown bats and little brown myotis. Capture of big brown bats (X2 = 53.738; P <0.001), little brown myotis (X2 = 21.900; P <0.001), and all species combined (X2 = 49.066; P <0.001) was greatest 1 – 2 hours after sunset. -

Bat Distribution in the Forested Region of Northwestern California

BAT DISTRIBUTION IN THE FORESTED REGION OF NORTHWESTERN CALIFORNIA Prepared by: Prepared for: Elizabeth D. Pierson, Ph.D. California Department of Fish and Game William E. Rainey, Ph.D. Wildlife Management Division 2556 Hilgard Avenue Non Game Bird and Mammal Section Berkeley, CA 9470 1416 Ninth Street (510) 845-5313 Sacramento, CA 95814 (510) 548-8528 FAX [email protected] Contract #FG-5123-WM November 2007 Pierson and Rainey – Forest Bats of Northwestern California 2 Pierson and Rainey – Forest Bats of Northwestern California 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Bat surveys were conducted in 1997 in the forested regions of northwestern California. Based on museum and literature records, seventeen species were known to occur in this region. All seventeen were identified during this study: fourteen by capture and release, and three by acoustic detection only (Euderma maculatum, Eumops perotis, and Lasiurus blossevillii). Mist-netting was conducted at nineteen sites in a six county area. There were marked differences among sites both in the number of individuals captured per unit effort and the number of species encountered. The five most frequently encountered species in net captures were: Myotis yumanensis, Lasionycteris noctivagans, Myotis lucifugus, Eptesicus fuscus, and Myotis californicus; the five least common were Pipistrellus hesperus, Myotis volans, Lasiurus cinereus, Myotis ciliolabrum, and Tadarida brasiliensis. Twelve species were confirmed as having reproductive populations in the study area. Sampling sites were assigned to a habitat class: young growth (YG), multi-age stand (MA), old growth (OG), and rock dominated (RK). There was a significant response to habitat class for the number of bats captured, and a trend towards differences for number of species detected. -

Nine Species of Bats, Each Relying on Specific Summer and Winter Habitats

Species Guide to Vermont Bats • Vermont has nine species of bats, each relying on specific summer and winter habitats. • Six species hibernate in caves and mines during the winter (cave bats). • During the summer, two species primarily roost in structures (house bats), • And four roost in trees and rocky outcrops (forest bats). • Three species migrate south to warmer climates for the winter and roost in trees during the summer (migratory bats). • This guide is designed to help familiarize you with the physical characteristics of each species. • Bats should only be handled by trained professionals with gloves. • For more information, contact a bat biologist at the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department or go to www.vtfishandwildlife.com Vermont’s Nine Species of Bats Cave Bats Migratory Tree Bats Eastern small-footed bat Silver-haired bat State Threatened Big brown bat Northern long-eared bat Indiana bat Federally Threatened State Endangered J Chenger Federally and State J Kiser Endangered J Kiser Hoary bat Little brown bat Tri-colored bat Eastern red bat State State Endangered Endangered Bat Anatomy Dr. J. Scott Altenbach http://jhupressblog.com House Bats Big brown bat Little brown bat These are the two bat species that are most commonly found in Vermont buildings. The little brown bat is state endangered, so care must be used to safely exclude unwanted bats from buildings. Follow the best management practices found at www.vtfishandwildlife.com/wildlife_bats.cfm House Bats Big brown bat, Eptesicus fuscus Big thick muzzle Weight 13-25 g Total Length (with Tail) 106 – 127 mm Long silky Wingspan 32 – 35 cm fur Forearm 45 – 48 mm Description • Long, glossy brown fur • Belly paler than back • Black wings • Big thick muzzle • Keeled calcar Similar Species Little brown bat is much Commonly found in houses smaller & lacks keeled calcar. -

Big Brown Bats

MINNESOTA PROFILE ig Brown Bat (Eptdicusfuscus) Description The big brown bat's scientific name, Eptesicus/uscus,® is Latin for dark house-flier. It is the more common of the two^^^WSj bat species sometimes found in houses and barns. An adult is about 5 inches from nose to tail and has a wingspan of about 10 inches. It has glossy copper or chocolate-brown fur and black membranes on its face, ears, wings, and tail. Long, slender finger bones are encased in leathery skin to make up its wings. This bat belongs to an order of mammals called Chiroptera, from the Creek for hand-wing. Range and habitat Big browns range throughout temperate North America into South America and many Caribbean islands. At home in city and country, they are among Minnesota's hardiest bats. Diet and echolocation They feed at night on flying insects, especially beetles. Nursing females ingest their body weight in insects each night. Bats locate prey by emitting high-frequency sound and listening for echoes bouncing off objects in front of them. The big brown's call is beyond human hearing. Reproduction Big browns mate in fall. In spring females form maternity colonies in attics, barns, and hollow trees. They give birth to one or two pups in early summer. Within a month, pups can fly and forage with their mothers. Hibernation They hibernate in caves, sewers, mines, and buildings. They are the last of Minnesota's cave bats to enter hibernation—usually forced in by a November storm—and among the first to leave in spring. -

Eared Bat (Corynorhinus Townsendii) in West Texas

MORPHOLOGICAL AND MOLECULAR VARIATION IN TOWNSEND’S BIG- EARED BAT (CORYNORHINUS TOWNSENDII) IN WEST TEXAS A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Angelo State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SCIENCE by TERESITA MARIE TIPPS May 2012 Major: Biology MORPHOLOGICAL AND MOLECULAR VARIATION IN TOWNSEND’S BIG- EARED BAT (CORYNORHINUS TOWNSENDII) IN WEST TEXAS by TERESITA MARIE TIPPS APPROVED: Loren K. Ammerman Robert C. Dowler Nicholas J. Negovetich Tom Bankston April 10, 2012 APPROVED: Dr. Brian May Dean of the College of Graduate Studies ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to begin by thanking my advisor Dr. Loren Ammerman, whose countless hours of patience and guidance led me to be the researcher I am today. She first recruited me to work in the molecular lab in 2008, and had it not been for this, I would not be working in the field that I am today. She inspires me to be the best I can be and gives me the confidence to know that I can accomplish anything I put my mind to. Without her advice and help throughout this thesis process, I probably would have gone crazy! I look forward to any future endeavors in which she can be involved. Secondly, I would like to thank all of my lab mates, Candace Frerich, Sarah Bartlett, Pablo Rodriguez-Pacheco, and Wes Brashear. Without their constant support and availability to bounce my ideas off of, I would not have been able to finish this project. I especially appreciate all of the help Dana Lee gave me as an undergraduate and a graduate, even though she did not live in San Angelo! Dana helped me understand various lab techniques and helped me troubleshoot several problems with PCR and sequencing that had me puzzled. -

Corynorhinus Townsendii): a Technical Conservation Assessment

Townsend’s Big-eared Bat (Corynorhinus townsendii): A Technical Conservation Assessment Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Species Conservation Project October 25, 2006 Jeffery C. Gruver1 and Douglas A. Keinath2 with life cycle model by Dave McDonald3 and Takeshi Ise3 1Department of Biological Sciences, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada 2Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, Old Biochemistry Bldg, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY 82070 3Department of Zoology and Physiology, University of Wyoming, P.O. Box 3166, Laramie, WY 82071 Peer Review Administered by Society for Conservation Biology Gruver, J.C. and D.A. Keinath (2006, October 25). Townsend’s Big-eared Bat (Corynorhinus townsendii): a technical conservation assessment. [Online]. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. Available: http:// www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/assessments/townsendsbigearedbat.pdf [date of access]. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors would like to acknowledge the modeling expertise of Dr. Dave McDonald and Takeshi Ise, who constructed the life-cycle analysis. Additional thanks are extended to the staff of the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database for technical assistance with GIS and general support. Finally, we extend sincere thanks to Gary Patton for his editorial guidance and patience. AUTHORS’ BIOGRAPHIES Jeff Gruver, formerly with the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, is currently a Ph.D. candidate in the Biological Sciences program at the University of Calgary where he is investigating the physiological ecology of bats in northern arid climates. He has been involved in bat research for over 8 years in the Pacific Northwest, the Rocky Mountains, and the Badlands of southern Alberta. He earned a B.S. in Economics (1993) from Penn State University and an M.S. -

Id & Ecology of OC Bats by Stephanie Remington V2

Bats Found in Orange County by Stephanie Remington FOOD HABITAT ROOST* MIGRATION / HIBERNATION STATUS NOTES Family Phyllostomidae nose ornamentation (leaf); migratory (do not hibernate) (Leaf-nosed bats) Mexican long-tongued near night-blooming cactae & caves, mines, bldgs fall migration to maternity roosts in has moved north to S. Cal. as habitat is lost in Mexico and as we plant more exotic batΨ Choeronycteris Nectar, pollen O agavae colonial (up to ~50) Mexico & Central America cactae & agavae; fall & winter records in S. Cal.; sensitive to disturbance mexicana Family Molossidae visible tail; migratory (usually do not hibernate); colonial; females form maternity colonies during the spring and summer months (Free-tailed bats) Mexican free-tailed bat variety of crevices; colonial (100s - migratory in parts of its range; appears one of the most common bats in OC; year-round activity, although reduced in winter; high altitudes C Tadarida brasiliensis agricultural pests 20 million) to overwinter in OC adapts well to urban environments; one pup born in Jun-July Pocketed free-tailed batΨ primarily large variable, from desert scrub to crevices of rugged cliffs; considered resident in San Diego very similar to the Mexican free-tailed bat, but slightly larger and with ears connected at Nyctinomops O moths pine-oak forest colonial County; status unknown in OC the midline; single pup, born in late Jun-Jul femorosaccus Big free-tailed batΨ almost entirely large usu crevices in cliffs; known only from a couple of records in OC; intermediate in size between pocketed free- rugged, rocky habitats seasonal migrant O Nyctinomops macrotis moths colonial tail and western mastiff bats; one pup, born late spring Western mastiff batΨ cliffs, occ. -

Bat Rabies and Other Lyssavirus Infections

Prepared by the USGS National Wildlife Health Center Bat Rabies and Other Lyssavirus Infections Circular 1329 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Front cover photo (D.G. Constantine) A Townsend’s big-eared bat. Bat Rabies and Other Lyssavirus Infections By Denny G. Constantine Edited by David S. Blehert Circular 1329 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2009 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Constantine, D.G., 2009, Bat rabies and other lyssavirus infections: Reston, Va., U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1329, 68 p. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Constantine, Denny G., 1925– Bat rabies and other lyssavirus infections / by Denny G. Constantine. p. cm. - - (Geological circular ; 1329) ISBN 978–1–4113–2259–2 1. -

Life History Account for Pallid

California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Interagency Wildlife Task Group PALLID BAT Antrozous pallidus Family: VESPERTILIONIDAE Order: CHIROPTERA Class: MAMMALIA M038 Written by: J. Harris Reviewed by: P. Brown Edited by: D. Alley, R. Duke DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND SEASONALlTY The pallid bat is a locally common species of low elevations in California. It occurs throughout California except for the high Sierra Nevada from Shasta to Kern cos., and the northwestern corner of the state from Del Norte and western Siskiyou cos. to northern Mendocino Co. A wide variety of habitats is occupied, including grasslands, shrublands, woodlands, and forests from sea level up through mixed conifer forests. The species is most common in open, dry habitats with rocky areas for roosting. A yearlong resident in most of the range. SPECIFIC HABITAT REQUIREMENTS Feeding: Takes a wide variety of insects and arachnids, including beetles, orthopterans, homopterans, moths, spiders, scorpions, solpugids, and Jerusalem crickets. The stout skull and dentition of this species allows it to take large, hard-shelled prey. Forages over open ground, usually 0.5-2.5 m (1.6-8 ft) above ground level. Foraging flight is slow and maneuverable with frequent dips, swoops, and short glides. Many prey are taken on the ground. Gleaning is frequently used, and a few prey are taken aerially. Can maneuver well on the ground. May carry large prey to a perch or night roost for consumption. Ingestion of fruit in one study (Howell 1980) was a result of feeding on frugivorous moths. Uses echolocation for obstacle avoidance; possibly utilizes prey-produced sounds while foraging. -

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats A agnella, Kerivoula 901 Anchieta’s Bat 814 aquilus, Glischropus 763 Aba Leaf-nosed Bat 247 aladdin, Pipistrellus pipistrellus 771 Anchieta’s Broad-faced Fruit Bat 94 aquilus, Platyrrhinus 567 Aba Roundleaf Bat 247 alascensis, Myotis lucifugus 927 Anchieta’s Pipistrelle 814 Arabian Barbastelle 861 abae, Hipposideros 247 alaschanicus, Hypsugo 810 anchietae, Plerotes 94 Arabian Horseshoe Bat 296 abae, Rhinolophus fumigatus 290 Alashanian Pipistrelle 810 ancricola, Myotis 957 Arabian Mouse-tailed Bat 164, 170, 176 abbotti, Myotis hasseltii 970 alba, Ectophylla 466, 480, 569 Andaman Horseshoe Bat 314 Arabian Pipistrelle 810 abditum, Megaderma spasma 191 albatus, Myopterus daubentonii 663 Andaman Intermediate Horseshoe Arabian Trident Bat 229 Abo Bat 725, 832 Alberico’s Broad-nosed Bat 565 Bat 321 Arabian Trident Leaf-nosed Bat 229 Abo Butterfly Bat 725, 832 albericoi, Platyrrhinus 565 andamanensis, Rhinolophus 321 arabica, Asellia 229 abramus, Pipistrellus 777 albescens, Myotis 940 Andean Fruit Bat 547 arabicus, Hypsugo 810 abrasus, Cynomops 604, 640 albicollis, Megaerops 64 Andersen’s Bare-backed Fruit Bat 109 arabicus, Rousettus aegyptiacus 87 Abruzzi’s Wrinkle-lipped Bat 645 albipinnis, Taphozous longimanus 353 Andersen’s Flying Fox 158 arabium, Rhinopoma cystops 176 Abyssinian Horseshoe Bat 290 albiventer, Nyctimene 36, 118 Andersen’s Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arafura Large-footed Bat 969 Acerodon albiventris, Noctilio 405, 411 Andersen’s Leaf-nosed Bat 254 Arata Yellow-shouldered Bat 543 Sulawesi 134 albofuscus, Scotoecus 762 Andersen’s Little Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arata-Thomas Yellow-shouldered Talaud 134 alboguttata, Glauconycteris 833 Andersen’s Naked-backed Fruit Bat 109 Bat 543 Acerodon 134 albus, Diclidurus 339, 367 Andersen’s Roundleaf Bat 254 aratathomasi, Sturnira 543 Acerodon mackloti (see A. -

Bats of the Savannah River Site and Vicinity

United States Department of Agriculture Bats of the Forest Service Savannah River Site and Vicinity Southern Research Station Michael A. Menzel, Jennifer M. Menzel, John C. Kilgo, General Technical Report SRS-68 W. Mark Ford, Timothy C. Carter, and John W. Edwards Authors: Michael A. Menzel,1 Jennifer M. Menzel,2 John C. Kilgo,3 W. Mark Ford,2 Timothy C. Carter,4 and John W. Edwards5 1Graduate Research Assistant, Division of Forestry, Wildlife and Fisheries, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV 26506; 2Research Wildlife Biologist, Northeastern Research Station, USDA Forest Service, Parsons, WV 26287; 3Research Wildlife Biologist, Southern Research Station, USDA Forest Service, New Ellenton, SC 29809; 4Graduate Research Assistant, Department of Zoology, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL 62901; and 5Assistant Professor, Division of Forestry, Wildlife and Fisheries, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV 26506, respectively. Cover photos: Clockwise from top left: big brown bats (photo by John MacGregor); Rafinesque’s big-eared bat (photo by John MacGregor); eastern red bat (photo by John MacGregor); and eastern red bat (photo by Julie Roberge). September 2003 Southern Research Station P.O. Box 2680 Asheville, NC 28802 Bats of the Savannah River Site and Vicinity Michael A. Menzel, Jennifer M. Menzel, John C. Kilgo, W. Mark Ford, Timothy C. Carter, and John W. Edwards Abstract The U.S. Department of Energy’s Savannah River Site supports a diverse bat community. Nine species occur there regularly, including the eastern pipistrelle (Pipistrellus subflavus), southeastern myotis (Myotis austroriparius), evening bat (Nycticeius humeralis), Rafinesque’s big-eared bat (Corynorhinus rafinesquii), silver-haired bat (Lasionycteris noctivagans), eastern red bat (Lasiurus borealis), Seminole bat (L. -

Bciissue22018.Pdf

BAT CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL ISSUE 2 • 2018 // BATCON.ORG CHIROPTERAN Research and development seeks to unlock and harness the secrets of bats’ techextraordinary capabilities THE CAVERN SPECIES SPOTLIGHT: THE SWEETEST OF YOUTH TRI-COLORED BAT FRUITS BECOME a MONTHLY SUSTAINING MEMBER Photo: Vivian Jones Vivian Photo: Grey-headed flying fox (Pteropus poliocephalus) When you choose to provide an automatic monthly donation, you allow BCI to plan our conservation programs with confidence, knowing the resources you and other sustaining members provide are there when we need them most. Being a Sustaining Member is also convenient for you, as your monthly gift is automatically transferred from your debit or credit card. It’s safe and secure, and you can change or cancel your allocation at any time. As an additional benefit, you won’t receive membership renewal requests, which helps us reduce our paper and postage costs. BCI Sustaining Members receive our Bats magazine, updates on our bat conservation efforts and an opportunity to visit Bracken Cave with up to five guests every year. Your consistent support throughout the year helps strengthen our organizational impact. TO BECOME A SUSTAINING MEMBER TODAY, VISIT BATCON.ORG/SUSTAINING OR SELECT SUSTAINING MEMBER ON THE DONATION ENVELOPE ENCLOSED WITH YOUR DESIRED MONTHLY GIFT AMOUNT. 02 }bats Issue 23 2017 20172018 ISSUE 2 • 2018 bats INSIDE THIS ISSUE FEATURES 08 CHIROPTERAN TECH For sky, sea and land, bats are inspiring waves of new technology THE CAVERN OF YOUTH 12 Bats could help unlock