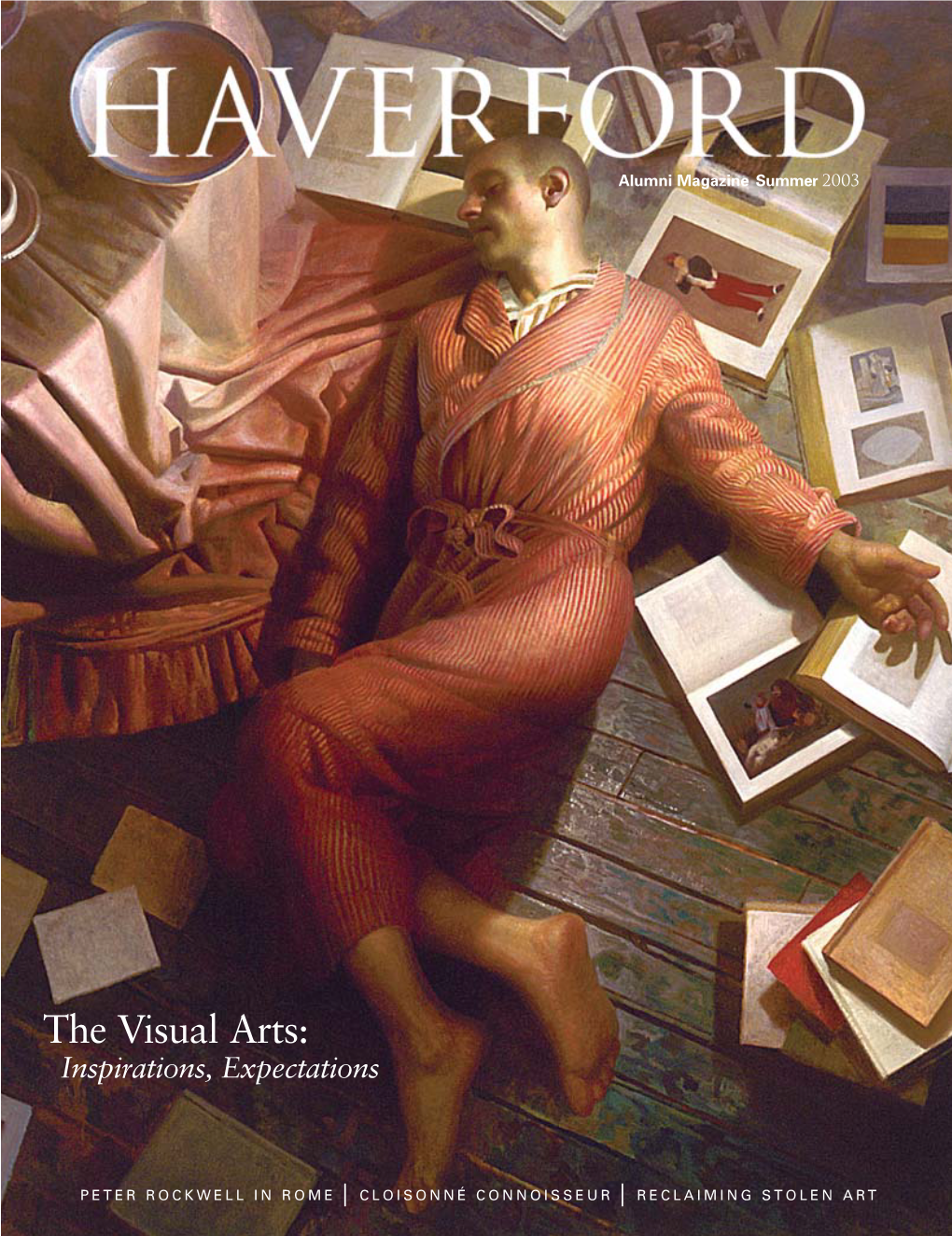

50287 Magazine Cover.Q4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Annual Report

MoNAMuseum of Northwest Art 2016 ANNUAL REPORT Annual Report 2016 D.indd 24 9/25/17 11:07 AM 3 From the President MISSION STATEMENT 4 Board & Staff The Museum of Northwest Art connects people with the art, diverse cultures and environments of the Northwest. 5 Exhibitions Visitor Testimonials VISION STATEMENT 10 The Museum of Northwest Art enriches lives in our diverse community by fostering essential 11 Acquisitions conversations and encouraging creativity through exhibitions and educational activities that explore the art of the Northwest. 12 MoNA Store COLLECTIONS & EXHIBITIONS 13 Education MoNA collects and exhibits contemporary art from across the Northwest, including Alaska, British Columbia, California, Idaho, Montana, Oregon and Washington. 15 Year in Review 17 Supporters 22 Volunteers Annual Report 2016 D.indd 1 9/25/17 11:07 AM 17,283 visits 42,866 website visits 100% visited for free 427 155 members volunteers 1,404 32 students visited with permanent collection 76 school tours acquisitions monamuseum.org 2 Annual Report 2016 D.indd 2 9/25/17 11:07 AM FROM THE PRESIDENT It is my great pleasure to share with you some of the successes achieved in 2016, made possible by your generous support. Because of you, more members of our community have experienced Northwest art in all of its facets through museum visits, program participation, and attendance at MoNA events and celebrations. MoNA’s commitment to providing free museum admission has fostered a broader and more engaged audience, making the museum accessible to more first-time visitors than ever before. MoNA, with your support, continues to fund significant investments in programming and collections. -

Encyklopédia Kresťanského Umenia

Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia americká architektúra - pozri chicagská škola, prériová škola, organická architektúra, Queen Anne style v Spojených štátoch, Usonia americká ilustrácia - pozri zlatý vek americkej ilustrácie americká retuš - retuš americká americká ruleta/americké zrnidlo - oceľové ozubené koliesko na zahnutej ose, užívané na zazrnenie plochy kovového štočku; plocha spracovaná do čiarok, pravidelných aj nepravidelných zŕn nedosahuje kvality plochy spracovanej kolískou americká scéna - american scene americké architektky - pozri americkí architekti http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:American_women_architects americké sklo - secesné výrobky z krištáľového skla od Luisa Comforta Tiffaniho, ktoré silno ovplyvnili európsku sklársku produkciu; vyznačujú sa jemnou farebnou škálou a novými tvarmi americké litografky - pozri americkí litografi http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:American_women_printmakers A Anne Appleby Dotty Atti Alicia Austin B Peggy Bacon Belle Baranceanu Santa Barraza Jennifer Bartlett Virginia Berresford Camille Billops Isabel Bishop Lee Bontec Kate Borcherding Hilary Brace C Allie máj "AM" Carpenter Mary Cassatt Vija Celminš Irene Chan Amelia R. Coats Susan Crile D Janet Doubí Erickson Dale DeArmond Margaret Dobson E Ronnie Elliott Maria Epes F Frances Foy Juliette mája Fraser Edith Frohock G Wanda Gag Esther Gentle Heslo AMERICKÁ - AMES Strana 1 z 152 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia Charlotte Gilbertson Anne Goldthwaite Blanche Grambs H Ellen Day -

The Weyerhauser Art Collection + MORE!

The Weyerhauser Art Collection + MORE! December 11th @ 5PM - EARLY START! 16% Buyers Premium In-House 19% Online & Phone Bidding Online Bidding Through LiveAuctioneers 717 S Third St Renton, WA (425) 235-6345 SILENT AUCTION ITEMS 6 4pc Antique Chinese Pheasant Silk Rank Lot 1,000's END @ 8:00PM Badges 10.5"x11" and 11"x12" Sets. Two Mandarin square front chest plate and back Lot Description patch sets. Polychrome silk embroidery. Staining and some edge fray. Qing dynasty. 1 Antique Chinese Silk Embroidered Dragon 7 7pc Antique Chinese Silk Embroidery. Robe 40"x52". Depicts four panels of Includes a large forbidden stitch panel forward facing five-clawed dragons in gold 27"x14", a pair of blue and white forbidden thread. Forbidden stitch sleeves with stitch lotus panels 8"x9.5" each, a round blossoming lotus flowers. Some staining. shou symbol panel 8.5" diameter, a pheasant Late Qing dynasty. Mandarin square rank badge 8"x8", and a 2 3pc Antique Chinese Pheasant Rank Badges gold thread leopard Mandarin square rank 11"x12" Each Approx. Each Mandarin chest badge 11"x12". There is also half a square has gold thread with silk chest plate rank badge. All have edge fray embroidered blossoming flowers. Also a and some soiling. Qing dynasty. coral colored beaded moon at the top corner. 8 Antique Chinese Imperial Dragon Kesi Silk Scattered fray and some staining. Qing Round Rank Badge 11" Diameter. Depicts a dynasty. gold thread five-clawed dragon with 3 4pc Antique Chinese Pheasant Rank Badges flaming pearl. Light soiling. Qing dynasty. 11"x12" Each Approx. -

Annual Year Dates Theme Painting Acquired Artists Exhbited Curator Location Media Used Misc

Annual Year Dates Theme Painting acquired Artists Exhbited Curator Location Media Used Misc. Notes 1st 1911 Paintings by French and American Artists Loaned by Robert C Ogden of New York 2nd 1912 (1913 by LS) Paintings by French and American Artists Loaned by Robert C Ogden of New York 3rd 1913 (1914 by LS) 1914/ (1915 from Lake Bennet, Alaska, Louise Jordan 4th Alaskan Landscapes by Leonard Davis Leonard Davis Purchase made possible by the admission fees to 4th annual LS) M1915.1 Smith Fifth Exhbition Oil Paintings at Randolph-Macon Groge Bellows, Louis Betts, Irving E. Couse, Bruce Crane, Frank V. DuMonds, Ben Foster, Daniel Garber, Lillian Woman's College: Paintings by Contemporary Matilde Genth, Edmund Greacen, Haley Lever, Robert Henri, Clara MacChesney, William Ritschel, Walter Elmer March 9- 5th 1916 American Artists, Loaned by the National Art Club Schofield, Henry B. Snell, Gardner Symons, Douglas Folk, Guy C. Wiggins, Frederick J. Waugh, Frederick Ballard Loaned by the National Arts Club of New York from their permanent collection by Life Members. April 8 of New York from Their Permanent Collection by Williams Life Members Exhibition by:Jules Guerin, Childe Hassam, Robert Louise Jordan From catalogue: "Randolph-Macon feels that its annual Exhibition forms a valuable part of the cultural opportunities of college 6th 1917 March 2-28 Jules Guerin, Childe Hassam, Robert Henri, J. Alden Weir Henri, J. Alden Weir Smith life." Juliu Paul Junghanns, Sir Alfred East, Henri Martin, Jacques Emile Blanche, Emond Aman-Jean, Ludwig Dill, Louise Jordan 7th 1918 International Exhbition George Sauter, George Spencer Watson, Charles Cottet, Gaston LaTouche, S.J. -

Fine Northwest Art & Objects Thursday

Fine Northwest Art & Objects Thursday March 28th @ 5:00PM 20% Buyers Premium In-House 25% Buyers Premium Online/Phone (425) 235-6345 SILENT AUCTIONS impressive transparent oval cabochon cut medium dark very slightly bluish green Lots 1,000’s End @ 8:00PM emerald beryl measuring 14.7x10.2x9.4mm. It is surrounded by (24) tapered baguette and Lot Description (16) round brilliant cut diamonds of approx. 1.2ctw average clarity VS-2, color G. It 1 Patek Philippe for Tiffany & Co. 18k Split weighs 17 grams and is unmarked. Current Second Chronograph Pocket Watch. Serial 2018 appraisal included from Northwest No.198112 with matching case number. 28 Gemological Laboratory. jewel movement with 5 adjusted positions 3 Lady's Citrine & Diamond 14k Ring Size 5. and 3 hot, cold, isochronism. Up down split Contains a large oval modified cut citrine second chronograph function. White quartz measuring 24.7x16.6x11.3mm. It is porcelain dial with black numerals and flanked by (15) round brilliant cut pave markers. 46mm case with monogram diamonds of .9 to 1.2mm diameter each. "WRC" on verso. This watch was presented Illegibly marked. It weighs 15 grams. Estate to Walter R. Cox (1868-1941), famed jewelry with no appraisal included. Harness Racing driver. Known as 4 2pc Lady's Natural Emerald Crystal & "Longshot" or "King of the Half Milers", Diamond 14k Floral Jewelry Set. Includes a Cox won the Hambletonian in 1929 with floral vine ring size 6. It has a natural Walter Dear and is in the Harness Racing emerald crystal specimen measuring Hall of Fame. -

Preview of the Visual Arts | April–May 2008

www.preview-art.com THE GALLERY GUIDE ALBERTA ■ BRITISH COLUMBIA ■ OREGON ■ WASHINGTON April/May 2008 SNAP CONTEMPORARY ART 190 West 3rd Ave., Vancouver, BC 604-879-7627 www.snapart.ca a new look for art on the Web contact subscribe search listings THE GALLERY GUIDE ALBERTA BRITISH COLUMBIA OREGON WASHINGTON GO CALENDAR PREVIEWS GALLERY WEBSITES find www.preview-art.com CONSERVATION CORNER SearchSearch forfor gallery,artwork artist, medium... 8 PREVIEW ■ APRIL/MAY 2008 COVER: Jan Crawford, Nightfall (2007), acrylic on canvas [Linda Lando Fine Art, Vancouver BC, Apr 24-May 3] previews Vol. 22 No. 2 ALBERTA 12 Lynn Richardson:Inter-Glacial Free 10 Calgary Trade agency.ca 14 Edmonton 16 Lethbridge Diana Burgoyne:Sound Drawings 18 Medicine Hat, Red Deer 12 Art Gallery of Calgary BRITISH COLUMBIA 14 Dorothy Knowles 18 Burnaby Douglas Udell Gallery, Edmonton 20 Campbell River, Chilliwack 21 Coquitlam, Courtenay 18 Jan Crawford & Sue Heatherington 22 Delta, Fort Langley, Gabriola Island Linda Lando Fine Art 23 Galiano Island, Grand Forks, Kamloops 38 34 Elspeth Pratt 25 Kaslo, Kelowna Charles H. Scott Gallery 26 Maple Ridge, Nanaimo, Nanoose Bay 38 Vessna Perunovich 27 Nelson, New Westminster, The Stride Gallery North Vancouver 29 Osoyoos, Parksville, Penticton 50 John Franklin Koenig:Northwest Master 30 Port Moody, Prince George, 56 Whatcom Museum Prince Rupert 31 Quadra Island, Qualicum Beach, 54 Stephen Waddell Richmond Contemporary Art Gallery 32 Salmon Arm, Salt Spring Island 56 Gary Pearson:The End is My Beginning 33 Sidney, Sidney-North -

— Eric Johnson

THE GRISTLE P.06 + FUZZ BUZZ P.09 + BUSINESS BRIEFS P.22 c a s c a d i a REPORTING FROM THE HEART OF CASCADIA WHATCOM*SKAGIT*SURROUNDING AREAS 01-01-2020 • ISSUE: 01 • V.15 BOOK CLUBBING Something for everyone P.10 FLY— ZONE Skagit Eagle Festival P.12 ERIC WINTER EXHIBITS JOHNSON Vivid visions The perks of at Jansen perfectionism Art Center P.16 P.14 FOOD Tour and Tasting: 2pm, Chuckanut Bay Distillery A brief overview of this Blind Tasting Experiment: 2pm-4pm, Seifert & 23 Jones Wine Merchants week’s happenings Potluck Social: 5pm-7pm, Sudden Valley Dance FOOD THISWEEK Barn VISUAL 20 Artist Talk and Demo: 2pm-5pm, Perry and Carl- son Gallery, Mount Vernon Voyager Opening: 5pm-7pm, Smith & Vallee Gal- B-BOARD lery, Edison The Language of Pattern Opening: 4pm-6pm, i.e. gallery, Edison 19 SUNDAY [01.05.20] FILM ONSTAGE The Curious Savage: 2:30pm, Alger Community 16 Church Depot Comedy Club: 8pm, Aslan Depot MUSIC Panty Hoes: 9:30pm, Rumors Cabaret 14 WORDS Resolutions for Writers: 11am-3pm, Village Books ART GET OUT 13 Rabbit Ride: 8:30am, Fairhaven Bicycle Deep Forest Experience: 11am-2pm, Rockport State Park STAGE FOOD 12 Country Breakfast: 8am-12pm, Rome Grange Langar: 11am-2pm, Guru Nanak Gursikh Gurdwara, Lynden GET OUT The Sky Colony will join a loaded lineup for a Give Me Shelter Solidarity Shindig VISUAL Ed Bereal Exhibit Closing: 12pm-5pm, Whatcom 10 Sat., Jan. 4 at the Lincoln Theatre. Museum’s Lightcatcher Building WORDS MONDAY [01.06.20] WEDNESDAY [01.01.20] ONSTAGE 8 Guffawingham: 9pm, Firefly Lounge GET OUT First Day Hike: 10am-12pm, Deception Pass Park DANCE CURRENTS Sudden Valley Polar Bear Plunge: 10am-12pm, Skagit Folk Dancers: 7pm, Bayview Civic Hall Marina Beach Park 6 Resolution Run, Padden Polar Dip: 11am, Lake WORDS Padden Attend an opening General Lit Book Group: 7pm, Village Books VIEWS Penguin Dip: 11am, Clear Lake Beach Polar Bear Plunge: 12pm, Birch Bay Beach Park reception for “Eat Your FOOD 4 Heart Out” Fri., Jan. -

Tacoma Art Museum Receives Gift of Key Works by Northwest Artists in the Vasiliki and William Dwyer Collection

MEDIA RELEASE June 30, 2016 Media Contact: Julianna Verboort, 253-272-4258 x3011 or [email protected] TACOMA ART MUSEUM RECEIVES GIFT OF KEY WORKS BY NORTHWEST ARTISTS IN THE VASILIKI AND WILLIAM DWYER COLLECTION Tacoma, WA — Tacoma Art Museum (TAM) has received a major promised gift from Seattle art collector Vasiliki Dwyer on behalf of her family and late husband William Dwyer, whose work as a federal judge had broad impact in the Pacific Northwest. The gift includes 22 works by important Northwest artists, and significant funding for the care and interpretation of the collection. The museum’s board of trustees accepted the promised gift on June 28, 2016. ―We are exceedingly grateful for the extraordinary gift of the Dwyer collection,‖ said Stephanie Stebich, Executive Director of Tacoma Art Museum. Stebich praised the gift as a beneficial contribution to TAM, the City of Tacoma, and the broader arts community. ―TAM’s remarkable collection has been built largely through transformative gifts like this one. The Dwyer’s gift joins major recent contributions from the Benaroya family, the Haub family, Dale Chihuly, Paul Marioni, and Anne Gould Hauberg.‖ The Vasiliki and William Dwyer Collection is the second large-scale bequest of Northwestern art and funds from prominent Seattle art collectors to TAM since January. Among the works are paintings by notable artists such as William Acheff, Kenneth Callahan, Richard Gilkey, William Ivey, Leo Kenney, Frank Okada, and Ambrose Patterson; sculptures by Julie Speidel and Margaret Ford; a key collage by Paul Horiuchi; mixed media by John Franklin Koenig and Wesley Wehr; encaustic by Joseph Goldberg; and photography by Johsel Namkung. -

Making Music out of Electricity, P.21 Nursery, Landscaping & Orchards

THE GRISTLE, P.6 DEVOTCHKA, P.20 FREE WILL, P.29 cascadia REPORTING FROM THE HEART OF CASCADIA SKAGIT*WHATCOM*ISLAND*LOWER B.C. 4.23.08 :: #17, v.03 :: FREE TRAVEL WRITER AND BIOGRAPHER PICO IYER On the OPENROADOPENROAD P.8 JOHN FRANKLIN KOENIG: REMEMBERING A MASTER, P.18 APRIL BREW’S DAY: QUAFF FOR A CAUSE, P.34 BEAF: MAKING MUSIC OUT OF ELECTRICITY, P.21 NURSERY, LANDSCAPING & ORCHARDS UNIQUE 34 34 FOOD PLANTS FOR 28 NORTHWEST CLASSIFIEDS GARDENS 24 ornamentals, natives, fruit FILM FILM Spring: Mon-Sat 10-5, Sun 11-4 20 20 . Goodwin Road, Everson MUSIC www.cloudmountainfarm.com 18 18 IT’S YOUR HORIZON. ART I know Cornwall Avenue is 17 under construction, But left coast is having a huge sale! STAGE STAGE 16 A Personal Fundraiser GET OUT We think it’s time to raise a little money for someone special — you. And our new Personal Fundraiser Savings th 14 4 Annual Account makes it easy. Simply deposit any amount up to $5,000, and we’ll pay a hefty 4.00% APY for up to six Crawfish Feed! WORDS months. But wait... There’s more! No checking account May 9 & 10 necessary. No early withdrawal penalties. Nobody 8 Starting at 5pm your knocking at your door. It’s just you and money. or until gone! Go ahead... You can smile. After all, it’s your Horizon, CURRENTS CURRENTS and it’s looking a little greener. All you can eat $ 99 Worth braving the 6 19 / person downtown construction: VIEWS VIEWS % Our floor models 4.00 APY ON BALANCES 4 are on sale.. -

Preview of the Visual Arts | January-February, 2010

w w w .p re v ie w -a r t. co m THE GALLERY GUIDE ALBERT A I BRITISH COLUMBI A I OREGO N I WASHINGTON February/March 2010 courtesy of Preview Graphics 2 PREVIEW I FEB/MAR 2010 # OPEN LATE ON FIRST THURSDAYS 8 PREVIEW I FEB/MAR 2010 Feb/Mar 2010 Vol. 24 No. 1 ALBERTA previews 10 Calgary 16 Drumheller, Edmonton 88 12 Lisa Birke: 20/10 Vision 18 Lethbridge Bau-Xi Gallery 19 Medicine Hat, Red Deer 14 Snap, Crackle, Pop BRITISH COLUMBIA University of Lethbridge Art Gallery 19 Abbotsford 20 Burnaby 26 Alexander Calder: A Balancing Act 22 Campbell River, Castlegar, Seattle Art Museum Chilliwack, Coquitlam 23 Courtenay, Delta, 32 Ken Monkman: The Triumph of Mischief Denman Island, Duncan Glenbow Museum 25 Fort Langley, Gabriola Island, ` Gibsons, Grand Forks 36 Bright Light: Public Art 26 Kamloops, Kaslo, Kelowna Downtown Eastside, various locations 27 Maple Ridge, Nanaimo 28 Nanoose Bay, Nelson, 26 38 James Nizam: Memorandoms New Westminster , North Vancou ver Gallery Jones 29 Osoyoos 46 Backstory: Nuuchaanulth 30 Penticton, Port Alberni, Port Moody, Prince George Ceremonial Curtains 31 Prince Rupert, Qualicum Beach, Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery Richmond, Salmon Arm 52 David Burdeny: Sacred and Secular 32 Salt Spring Island, Sidney, Sidney-North Saanich Jennifer Kostuik Gallery Herringer Kiss Gallery 33 Silver Star Mountain, Sooke, 52 Squamish, Summerland 60 Visceral Bodies 34 Sunshine Coast, Surrey, Vancouver Art Gallery Tsawwassen 35 Vancouver 62 Art and the Winter Olympic Games 61 Vernon 65 Victoria 66 Great New Wave: Contemporary -

Sandra Zeiset Richardson

F O S T E R / W H I T E G A L L E R Y LOIS GRAHAM 1930 – 2007 Education Washington University School of Fine Arts, St. Louis, MO Knox College, Galesburg, IL Private study with Lothar Schall, Stuttgart, Germany Factory of Visual Art Centrum Foundation, Master Workshops with Jack Tworkov and Nathan Oliviera Selected Solo Exhibitions 2010 ‘Fierce Abstraction: From the Archives,’ Foster/White Gallery, Seattle, WA 2007 ‘New Works,’ Foster/White Gallery, Seattle, WA 2004 ‘Survey,’ Foster/White Gallery, Seattle, WA 2002 Foster/White Gallery, Seattle, WA 2000 ‘New Paintings and Works on Paper,’ Foster/White Gallery, Seattle, WA 1998 ‘Painting and Monotypes,’ Foster/White Gallery, Seattle, WA 1996 ‘New Work,’ Foster/White Gallery, Kirkland, WA 1995 The Whatcom Museum, Bellingham, WA 1994 Foster/White Gallery, Seattle, WA 1991 Foster/White Gallery, Seattle, WA 1989 Foster/White Gallery, Seattle, WA 1988 Pacific Lutheran University, Tacoma, WA Helen S. Smith Gallery, Green River Community College, WA 1987 ‘Recent Paintings,’ Foster/White Gallery, Seattle, WA 1986 Harris Gallery, Houston, TX 1985 Foster/White Gallery, Seattle, WA ‘Lois Graham: A Decade in Review,’ Bellevue Art Museum, Bellevue, WA 1984 Kirk deGooyer Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 1983 Artemisia Gallery, Chicago, IL 1982 Foster/White Gallery, Seattle, WA Kirk deGooyer Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 220 Third Avenue South, Suite 100, Seattle, WA 98104 206.622.2833 [email protected] www.fosterwhite.com 1981 Foster/White Gallery, Seattle, WA 1979 Artists Gallery, Seattle, WA 1977 Artists Gallery, -

Premier Modernism, Fine Art & Asian Artifacts!

Premier Modernism, Fine Art & Asian Artifacts! Thursday June 30th @ 2:00PM 16% Buyers Premium In-House 19% Buyers Premium Online/Phone 717 S Third St Renton (425) 235-6345 SILENT AUCTIONS 4A Set of Hans Wegner for Fritz Hansen "Heart" Teak Stacking Chairs 28.5"x17"x20" Each. Lots 1,000’s End @ 8:00PM Set of four danish teak stacking tripod chairs. Burned in "FH" Denmark with Raymor Lot Description aluminum retailer tags on bottom. Excellent condition. Mid century modern. 1 Arne Jacobsen for Fritz Hansen Egg Chair & 5 Finn Juhl for Niels Vodder Teak Dining Ottoman. Original black leather armchair and Table 28.5"x71"x47". Denmark oval dining ottoman with aluminum feet. Chair measures table with two original 21.5" leaves. Comes 42"x35"x30" and ottoman is 14"x21"x15". with original fitted pads. Illums Bolighus Each piece has its original Illums Bolighus aluminum retailer tag on bottom. Excellent, aluminum retailer tag attached to bottom. original condition. Danish mid century Scattered edge wear to leather. Overall modern. excellent condition. Designed in 1958 for 6 Set of 8 Niels Moller Denmark Teak Dining Fritz Hansen of Denmark. Chairs. Includes two armchairs 30"x23"x22" 2 Pair of Ib Kofod-Larsen Denmark Teak and six straight side chairs 29.5"x20"x19" Lounge Chairs 30"x25"x26" Each. Teak with original upholstery. Each has aluminum frames with original sea green upholstery. J.L. Moller Mobelfabrik button on bottom. Unmarked. One has a small crack to screw Also original Illums Bolighus aluminum joint on verso. Overall excellent condition. retailer label on bottom.