A River of Unrivaled Advantages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Quality

CULTURAL QUALITY Historic Hills Scenic Byway puts visitors right in the middle of rural, small-town Iowa. The key cultural Cultural Quality Definition: quality is small-town Americana and agriculture and Cultural resources are derived from the distinctive cultural resources are also tightly woven with history. communities that influence the byway character. In addition, there are a surprising number of art Events, traditions, food, and music provide insight resources, ranging from diverse artisans at into the unique cultural qualities of the area. These th Bentonsport to pottery made in 19 century molds. cultural qualities are not necessarily expressed in The themes of art, Americana and agriculture the landscape. Culture encompasses all aspects of a converge at the American Gothic House in Eldon. community’s life, and it may be difficult to decide what is necessary to define cultural resources as Amish and Mennonite settlements add another intrinsic qualities. Aspects to consider include dimension to the Corridor’s cultural resources. geography, economy, community life, domestic life and artistic genres. ASSESSMENT AND CONTEXT The assessment of the Byway’s cultural quality focused on resources related to small town life, have modern commerce, the architecture and age of agriculture, Amish and Mennonites communities, and the buildings give the towns a sense of place not often visual arts. present in larger communities. What aspects of small-town life will visitors see? A Small–Town Life hotel that has been offering lodging since 1899. Small-town life as a quality is difficult to describe. Small, locally owned grocery stores and The Corridor towns are, indeed, small - Bloomfield is restaurants. -

A Statistical Study of the Variations in Des Moines River Water Quality Lewis Metzler Naylor Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1975 A statistical study of the variations in Des Moines River water quality Lewis Metzler Naylor Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Civil Engineering Commons, and the Oil, Gas, and Energy Commons Recommended Citation Naylor, Lewis Metzler, "A statistical study of the variations in Des Moines River water quality " (1975). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 5496. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/5496 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

April 22—23, 2016 Grand View University

PROCEEDINGS OF THE 128TH ANNUAL MEETING OF THE IOWA ACADEMY OF SCIENCE April 22—23, 2016 Grand View University FRIDAY SCHEDULE Time Events Location Page 7:30 a.m. IJAS Registration SC Lobby 2, 3 7:30 a.m. - 4:30 p.m. IAS Bookstore Open SC Lobby 2, 3 8:00 a.m. Registration Desk Opens SC Lobby 2, 3 8:00 a.m. Silent Auction begins SC Lobby 2, 3 8:00 a.m. -10:30 a.m. Morning Snack SC Lounge 2 8:00 a.m. - 3:00 p.m. IJAS Program Schedule 10 8:00 a.m. -10:45 a.m. IJAS Poster Presentations SC Lounge 7-9 SC—See IJAS Schedule 8:00 a.m. - 10:45 a.m. IJAS Oral Presentations 10 11:00 a.m. - Noon General Session I SC Speed Lyceum 12 Noon - 1:15 p.m. IJAS Award Luncheon Valhallah Dining 11,12 1:15 p.m. -1:40 p.m. IAS Business Meeting SC Plaza View Room 12 Exploring Lunar & Planetary SC Conference A & B 1:30 p.m. -2:25 p.m. 10 Science with NASA IJAS Grand View University 1:30 p.m. - 4:00 p.m. SC Conference A,B,C 10 Event 1:45 p.m. - 4:30 p.m. Symposiums A, B, C See Symposiums Schedule 13, 14 4:30 p.m. - 5:45 p.m . Senior Poster Session SC Lounge 14 4:45 p.m. - 6:00 p.m. Social Hour SC Lounge 14 6:00 p.m. -7:30 p.m. President’s Banquet Valhallah Dining 15 7:45 p.m. -

Scanned Document

125 Years m 1866-1991 Tower Times US Army Corps of Engineers Volume 13 No. 10 October 1991 North Central Division Rock Island District Col. John R. Brown Commander's Corner To talk of many things ... Congratulations and appreciation for through donations to the charity of our Rock Island District's 125 years of service choice. You should be contacted by a were expressed by the Quad Cities Council keyperson who will provide you all the in of the Chambers of Commerce with a din formation needed to make a decision. If ner and program on the 4th of September. you choose to donate, you can specify the Speakers were Congressman Leach of agency( s) who will benefit from your gift. Iowa, Mayor Schwiebert of Rock Island, As a group, we have been generous in the Commissioner Winborn of Scott County, past and I expect that trend will continue and Mr. Charles Ruhl of the Council of so I thank you for your generosity in ad Chambers of Commerce. It was a pleasant vance. evening on the banks of the Mississippi Safety is still a concern for all of us. We near the Visitors Center with a large tur are making progress in reducing both the nout of guests and our people. I was very rate and severity of the accidents ex proud to accept the speakers' laudatory perienced. However, the rate is not zero so comments on behalf of all the past and we can still improve. I encourage present members of the Rock Island Dis everybody to review their work habits from trict. -

Time for a Field Trip!

Field Trip Curriculum for 4th-6th Grade Students Time for a Field Trip! Pre-Field Trip Warm Up____________________ Starved Rock and Matthiessen State Parks IDNR Educational Trunks: People and Animals from Illinois’ Past https://www2.illinois.gov/dnr/education/Pages/ ItemsForLoan.aspx Group Permit Form (to be completed prior to visit) https://www2.illinois.gov/dnr/Parks/Activity/Pages/ StarvedRock.aspx Enjoy Your Trip! Starved Rock Wigwam STEAM Activity- Pages 2 & 3 “Starved Rock History and Activity Packet - Pages 4-10 Thank you for your Day of Field Trip Activities________________________ interest in Starved 1.5 –2 hours Rock State Park. The Field Trip Pack for Teachers following is a packet of https://www2.illinois.gov/dnr/education/Pages/ materials intended to assist teachers in using ItemsForLoan.aspx the site for field trips. Hike to Starved Rock and French Canyon .8 miles roundtrip For your convenience, Map: https://www2.illinois.gov/dnr/Parks/Pages/ we have assembled a StarvedRock.aspx list of activities that Scavenger Hunt - Page 11 can be incorporated Tour the Visitor Center exhibits into the classroom and In the Shadow of the Rock film—15 minutes daily lesson plans in conjunction with a POST-VISIT ACTIVITIES field trip to Starved Rock State Park. • Write your own Starved Rock Story: “My Day at Starved Rock State Park” Template Page 12 2 2 Wigwam Construction: Engineering 3 The Kaskaskia People lived in villages of small round houses called wigwams. What you need: 6 for each student or pair of (buddy up) Square pieces of cardboard box for each student/pair Circle to trace/tree bark sheets Instructions: Have students trace the circle template onto their square piece of cardboard. -

West Fork Des Moines River and Heron Lake TMDL Implementation Plan

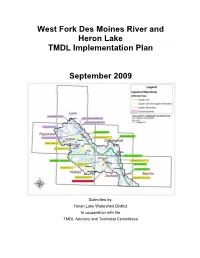

West Fork Des Moines River and Heron Lake TMDL Implementation Plan September 2009 Submitted by: Heron Lake Watershed District In cooperation with the TMDL Advisory and Technical Committees Preface This implementation plan was written by the Heron Lake Watershed District (HLWD), with the assistance of the Advisory Committee, and Technical Committee, and guidance from the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) based on the report West Fork Des Moines River Watershed Total Maximum Daily Load Final Report: Excess Nutrients (North and South Heron Lake), Turbidity, and Fecal Coliform Bacteria Impairments. Advisory Committee and Technical Committee members that helped develop this plan are: Advisory Committee Karen Johansen City of Currie Jeff Like Taylor Co-op Clark Lingbeek Pheasants Forever Don Louwagie Minnesota Soybean Growers Rich Perrine Martin County SWCD Randy Schmitz City of Brewster Michael Hanson Cottonwood County Tom Kresko Minnesota Department of Natural Resources - Windom Technical Committee Kelli Daberkow Minnesota Pollution Control Agency Jan Voit Heron Lake Watershed District Ross Behrends Heron Lake Watershed District Melanie Raine Heron Lake Watershed District Wayne Smith Nobles County Gordon Olson Jackson County Chris Hansen Murray County Pam Flitter Martin County Roger Schroeder Lyon County Kyle Krier Pipestone County and Soil and Water Conservation District Ed Lenz Nobles Soil and Water Conservation District Brian Nyborg Jackson Soil and Water Conservation District Howard Konkol Murray Soil and Water Conservation District Kay Clark Cottonwood Soil and Water Conservation District Rose Anderson Lyon Soil and Water Conservation District Kathy Smith Martin Soil and Water Conservation District Steve Beckel City of Jackson Mike Haugen City of Windom Jason Rossow City of Lakefield Kevin Nelson City of Okabena Dwayne Haffield City of Worthington Bob Krebs Swift Brands, Inc. -

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc. 7407 La Jolla Boulevard www.raremaps.com (858) 551-8500 La Jolla, CA 92037 [email protected] Map of the Des Moines Rapids of the Mississippi River. Drawn by Lt. M.C. Meigs & Henry Kayser Stock#: 53313 Map Maker: Lee Date: 1837 Place: Washington, DC Color: Uncolored Condition: VG+ Size: 21 x 50 inches Price: $ 345.00 Description: Fort Des Moines, Wisconsin Territory Finely detailed map of the section of the Mississippi River, showing the Des Moines Rapids in the area of Fort Des Moines, based upon the surveys of Lieutenant Robert E. Lee of the US Corps of Engineers. The Des Moines Rapids was one of two major rapids on the Mississippi River that limited Steamboat traffic on the river through the early 19th century. The Rapids between Nauvoo, Illinois and Keokuk, Iowa- Hamilton, Illinois is one of two major rapids on the Mississippi River that limited Steamboat traffic on the river through the early 19th century. The rapids just above the confluence of the Des Moines River were to contribute to the Honey War in the 1830s between Missouri and Iowa over the Sullivan Line that separates the two states. The map shows the area between Montrose, Iowa and Nauvoo, Illinois in the north to Keokuk, Iowa and Hamilton, Illinois. On the west bank of the river, the names, Buttz, Wigwam, McBride, Price, Dillon, Withrow, Taylor, Burtis and Store appear. On the east bank, Moffat, Geo. Middleton, Dr. Allen, Grist Mill, Waggoner, Cochran, Horse Mill, Store, Mr. Phelt, and Mrs. Gray, the latter grouped around the town of Montebello. -

The Mormon Settlement at Nashville, Lee, Iowa

THE MORMON SETTLEMENT AT NASHVlLLE, LEE, IOWA: ONE OF THE SATELLITE SETTLEMENTS OF NAWOO Maurine Carr Ward The Missouri expulsion in 1838-39 found most of Des Moines. WhenIsrael Barlow met Galland, the owner the Mormon refugees heading for Quincy, Illinois. Israel of the army barracks, Galland began negotiations to buy Barlow and others, however, traveled northfromDaviess not only land in Iowa in the Half Breed Tract but also the County and then followed along the southern tier of Iowa land and buildings in Commerce. until they arrived at the abandoned barracks of Fort Des Moines, now Montrose, Iowa This area was located in The weaq Mormons flocked to Commerce where the "Half Breed Tract," 119,000 acres set apart on 4 they began the task of draining the swampy land and August 1824 for the mixed-blood natives belonging to building their city, shortly thereafter renamed Nawoo. the Sacs and Foxes but later sold to the whites for home- Soon, other Saints moved into the newly purchased land steading.1 in Iowa4 where the Church had bought the town site of Nashville and 20,000 surrounding acres, 30,000 acres One of the first settlers is a man named Isaac near and including Montrose, and other lands-some Galland, who not only purchased land in Iowa but also 120,000 in all. Individuals also purchased land in bought land across the Mississippi River in Commerce, Ambrosia, Keokuk, and additional areas in Iowa Illinois. Galland's property, about three miles below pre- sent-day Monmse, was procured in 1829. Dr. -

Upper Mississippi River Basin Association Ppa N I81i1uppi Jl.I:Ru C1 ~1.D

Mississippi River UMR HAB Response Basin Association Resource Manual LAUREN SALVATO GREAT PLAINS AND MIDWEST HARMFUL ALGAL BLOOMS CONFERENCE FEBRUARY 5, 2020 CWAReach #6 c~~::::hD#~m 11 - Lock t •m 13 Lock and Dam 13 -Iowa River -.z-- -- CWA Reach #8 \ Lower Impounded Iowa River -Des Moines River CWAReach #9 Des Moines Rive r - Lock and DamI 21 CWA Reach #10 \ Lock and Dam 21 - Cuivre River\ CWA Reach #11 ( Cuivre River -Missouri River CWA Reach #12 ) Open River--_____J Missouri River - Kaskaskia River ,-'----~------- .? CWA Reach #13 Legend Kaskaskia River - Ohio River - Reach Boundaries -:'c- ape G.irar ds eau Floodplain Reaches ~ Cairo.) -- Upper Impounded - Lower Impounded 0 50 100 200 Miles About UMRBA • Regional interstate organization formed in 1981 by the Governors of Minnesota, Wisconsin, Illinois, Iowa, and Missouri • Facilitate dialogue and cooperative action regarding water and related land resource issues on behalf of the five basin states Photo credit: US FWS UMRBA Issue Areas Ecosystem Commercial Health Navigation Clean Hazardous Water Spills Aquatic Flooding Nuisance Species Photo credit: MVS Flickr UMRBA Water Quality Groups Water Quality Executive Committee • Policy making body • Influences water quality areas of focus Water Quality Task Force • Technical body • Makes recommendations to the Executive Committee and takes on new directives Photo: USFWS Refuge Flicker Mississippi River Harmful Algal Bloom HABs Response Resource Manuall • Communication List • Response Tools and Resources • Maps and Spatial References • Communication Tools • Algae/Toxin Guidelines • Capacities Compilation January 2020 http://umrba.org/wq/umr-hab-response- resource-manual.pdf Upper Mississippi River Basin Association ppa N i81i1uppi Jl.i:ru C1_~1.D. -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet

?/ , V, • i Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF TH! INTERIOR (Dec. 1968) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Iowa COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES _____Van INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) APR z JLJ9J2 Bentonsport AND/OR HISTORIC: Bentonsport liiiliiiiilit|......... .....,.;.-.•. ................. STREET AND NUMBER: _________Washington Township, rural route, Keosauqua, Iowa CITY OR TOWN: Keosauqua Iowa 52565 14 Van Buren 177 liiiiiiliiiiilliNi CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE IS) OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC District | | Bui Iding D Public Public Acquisition: Occupied CD Yes: Site (Xl Structure D Private In Process [ | Unoccupied Restricted Q Both Being Considered Preservation work Unrestricted 3 Object Q in progress No: D U PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) ID Agricultural | | Government | | Park Transportation ___O^_^ Comments Commercial d) Industrial Q Private Residence Other rSM$T^r;\ U.Q //_———— /-vO'- - ~ *:>/ Educational (x) Military Q Religious Entertainment fc) Museum {£] Scientific OWNERS NAME: Van Buren County Conservation Board UJ STREET AND NUMBER: UJ Courthouse, Van Buren County Cl TY OR TOWN: Keosauqua Iowa COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS. ETC: Van Buren County Courthouse STREET AND NUMBER: __________City of Keosauqua Cl TY OR TOWN: Keosauqua Iowa 14 APPROXIMATE ACREAGE OF NOMINATED PROPERTY: 35 TITLE OF SURVEY: County Outdoor Recreation Plan...Master restoration plan by Bill Wagner DATE OF SURVEY: 2/11/69 Federal f~| State County Local DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: County Courthouse of Van Buren County STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: Keosauqua Iowa 52565 14 (Check One) CONDITION Excellent | | Good Q3 Fair E Deteriorated Q] Ruins a Unexposed a (Check One) (Check One) INTEGRITY Altered | | Unaltered (x] Moved G Original Site g] DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (if known) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The remaining store buildings in Bentonsport appear today much as they did originally. -

Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma (Oklahoma Social Studies Standards, OSDE)

OKLAHOMA INDIAN TRIBE EDUCATION GUIDE Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma (Oklahoma Social Studies Standards, OSDE) Tribe: Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma Tribal website(s): http//www. iowanation.org 1. Migration/movement/forced removal Oklahoma History C3 Standard 2.3 “Integrate visual and textual evidence to explain the reasons for and trace the migrations of Native American peoples including the Five Tribes into present-day Oklahoma, the Indian Removal Act of 1830, and tribal resistance to the forced relocations.” Oklahoma History C3 Standard 2.7 “Compare and contrast multiple points of view to evaluate the impact of the Dawes Act which resulted in the loss of tribal communal lands and the redistribution of lands by various means including land runs as typified by the Unassigned Lands and the Cherokee Outlet, lotteries, and tribal allotments.” • Original Homeland – present day state of Iowa • Location In Oklahoma – Perkins, Oklahoma The Iowa or Ioway, lived for the majority of its recorded history in what is now the state of Iowa. The Iowas call themselves the Bah-Kho-Je which means grey snow, probably derived from the fact that during the winter months their dwellings looked grey, as they were covered with fire- smoked snow. The name Iowa is a French term for the tribe and has an unknown connection with 'marrow.' The Iowas began as a Woodland culture, but because of their migration to the south and west, they began to adopt elements of the Plains culture, thus culminating in the mixture of the two. The Iowa Nation was probably indigenous to the Great Lakes areas and part of the Winnebago Nation. -

April 2020 "Heron"

Clinton County The Heron Conservation Newsletter of Clinton County Conservation Volume 42 Number 1 January - April, 2020 The 2019 Fall Hawk Watch at Eagle Point Park: A Memorable Day for Migrating Raptors and a First State Record by Kelly J. McKay and Mark A. Roberts stopped by during the event, 55% fewer than last year. The brave souls who did show up however, were treated to a good day of raptor migration, as well as many other species. We observed 13 species of raptors (10 species last year) and 474 individual birds (172 birds last year). These included: 73 turkey vultures, a noteworthy 19 os- prey, 1 northern harrier, 15 sharp-shinned hawks, 2 Cooper’s hawks, 40 bald eagles, 2 red-shouldered hawks, 272 broad-winged hawks, 3 red-tailed hawks, 1 barred Owl, 2 American kestrels and 6 merlins. Additionally, we had an amazing number of 38 peregrine falcons! Besides raptors, we recorded an impressive number of total birds for the day (82 species). Among these, some of the more noteworthy observations included: 32 wood ducks, 13 northern pintail, a very early single female com- mon goldeneye, 240 chimney swifts, 6 caspian terns, 764 double-crested cormorants, 295 American white pelicans, 12 red-eyed vireos, 41 blue jays, 2 winter wrens, 20 gray The Clinton County Conservation Board decided to hold its catbirds, 15 pine siskins, 70 American goldfinches, 25 Second Annual Fall Raptor Migration Watch at Eagle Point white-throated sparrows, and 35 northern cardinals. Park in Clinton, Iowa on September 28, 2019. Once again, we chose this date to coincide with the peak period of broad-winged hawk migration through the Upper Midwest, when large numbers of these raptors can be observed in migratory flocks called “kettles.” This site is very good for observing a variety of migrating raptors, since it is located on top of the high bluffs overlooking the Upper Mississippi at the southern extent of the “driftless area” of Iowa.