Rapid Response Achieves Eradication – Chub in Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISFC Annual Report 1999

1999 Salmon, Sea Trout . 3 Location Map for Awards Presentation in Doyle Burlington Brown Trout (Lake) . 4 Brown Trout (River) . 5 Bream . 6 Pike (Lake), Pike (River) . 8 Carp . 10 Eel, Roach/Bream Hybrid . 11 Rudd/Bream Hybrid, Perch . .12 Tench . 13 Bass . 14 Coalfish, Cod, Conger Eel, Dab, Greater Spotted Dogfish . 15 Lesser Spotted Dogfish, Spur Dogfish . 16 Flounder, Garfish, Grey Gurnard . 17 Red Gurnard, Tub Gurnard, Ling . 18 Mackerel . 19 Grey Mullet, Plaice . 20 ONTENTS Pollack, Pouting . 21 Blonde Ray, Homelyn Ray, Painted Ray . 22 Sting Ray, Three Bearded Rockling, Twaite Shad . 24 C Blue Shark . 25 Tope, Torsk, Ballan Wrasse, Cuckoo Wrasse . 26 New Records, Ten Species Award, Ten Pin Awards, Special Award for Juveniles, The Minister’s Award, . .27 Revised Specimen Weight/New Class, Special Notice, Limitation on Number of Claims, Exclusion from Specimen Status, Weighing of Fish, Metrification . 28 Common Skate, Captors Addresses, Distribution of Specimen Awards . .29 Acknowledgements, Presentation of Awards 1998, Fund Raising . 30 Accounts, Donations . 31 Use of the information contained in this report for press articles Balance Sheet . 32 and publicity is encouraged. It may be quoted without charge, Irish Record Fish Listing . 33 provided the source is acknowledged. Schedule of Specimen Weights (Revised) . 35 The report is copyright and prior permission to reproduce the Rules . 37 data for any other purpose other than reasonable review or Weighing Scale Certification – List of Centres . .40 analysis must be obtained in writing from the Irish Specimen Fish “Read it Carefully” by Des Brennan . 42 Committee. “Maybe we’ll stay at home this year!” by Derek Evans . -

EREP 2017 Annual Report

EREP 2017 Annual Report Inland Fisheries Ireland & the Office of Public Works Environmental River Enhancement Programme Acknowledgments The assistance and support of OPW staff, of all grades, from each of the three Drainage Maintenance Regions is gratefully appreciated. The support provided by regional IFI officers, in respect of site inspections and follow up visits and assistance with electrofishing surveys is also acknowledged. Overland access was kindly provided by landowners in a range of channels and across a range of OPW drainage schemes. Project Personnel Members of the EREP team include: Dr. James King Brian Coghlan MSc (Res) Amy McCollom IFI Report Number: IFI/2018/1-4430 CITATION: Coghlan, B., McCollom, A., and King, J.J. (2018) Environmental River Enhancement Programme Summary Report 2017. Inland Fisheries Ireland, 3044 Lake Drive, Citywest, Dublin 24, Ireland. © Inland Fisheries Ireland 2018 The report includes Ordnance Survey Ireland data reproduced under OSi Copyright Permit No. MP 007508. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Ordnance Survey Ireland and Government of Ireland copyright. © Ordnance Survey Ireland, 2016. Table of Contents 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 The Inny Survey Programme ..................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Long-term Monitoring ................................................................................................................ -

Spawning Strategies in Cypriniform Fishes in a Lowland River Invaded By

Hydrobiologia (2020) 847:4031–4047 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-020-04394-9 (0123456789().,-volV)( 0123456789().,-volV) PRIMARY RESEARCH PAPER Spawning strategies in cypriniform fishes in a lowland river invaded by non-indigenous European barbel Barbus barbus Catherine Gutmann Roberts . J. Robert Britton Received: 15 May 2020 / Revised: 11 August 2020 / Accepted: 23 August 2020 / Published online: 4 September 2020 Ó The Author(s) 2020 Abstract Spawning strategies of lowland river remained relatively small by the end of their growth fishes include single spawning, where reproduction season (October). For dace Leuciscus leuciscus, only generally occurs in early spring to provide 0? fish single spawning events were evident, but with 0? dace with an extended growth season through the summer, always being relatively large. Therefore, multiple but with a high risk of stochastic mortality events spawning appears to be a common strategy that occurring, such as early summer floods. This risk can provides resilience in 0? fish against stochastic be reduced by multiple or protracted spawning strate- mortality events in lowland rivers. gies, where 0? fish are produced over an extended period, often into mid-summer, but with the trade-off Keywords Spawning strategies Á Invasion biology Á being a shorter growth season. The spawning strate- Recruitment Á Cypriniform Á Barbus gies of cypriniform fish were explored in the River Teme, a spate river in Western England, which has non-indigenous European barbel Barbus barbus pre- sent. Sampling 0? fish in spring and summer and Introduction across three spawning periods, B. barbus, chub Squalius cephalus and minnow Phoxinus phoxinus In temperate lowland rivers, larval and juvenile fish in always revealed multiple spawning events, with 0? their first year of life (‘0?’) may face episodic flood fish of \ 20 mm present in samples collected from events that can be deleterious to their cohorts, June to August. -

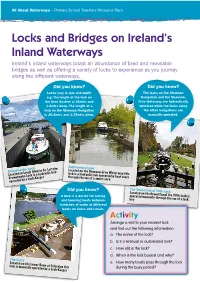

Locks and Bridges on Ireland's Inland Waterways an Abundance of Fixed

ack eachers Resource P ways – Primary School T All About Water Locks and Bridges on Ireland’s Inland Waterways Ireland’s inland waterways boast an abundance of fixed and moveable bridges as well as offering a variety of locks to experience as you journey along the different waterways. Did you know? Did you know? The locks on the Shannon Navigation and the Shannon- Locks vary in size and depth Erne Waterway are hydraulically e.g. the length of the lock on operated while the locks along the Erne System is 36mtrs and the other navigations are 1.2mtrs deep. The length of a manually operated. lock on the Shannon Navigation is 29.2mtrs and 1.35mtrs deep. Ballinamore Lock im aterway this Lock . Leitr Located on the Shannon-Erne W n in Co ck raulic lock operated by boat users gh Alle ulic lo lock is a hyd Drumshanbon Lou ydra ugh the use of a smart card cated o ock is a h thro Lo anbo L eeper rumsh ock-K D ed by a L operat The Grand Canal 30th Lock Did you know? Located on the Grand Canal the 30th Lock is operated manually through the use of a lock A lock is a device for raising key and lowering boats between stretches of water of different levels on rivers and canals. Activity Arrange a visit to your nearest lock and find out the following information: a. The name of the lock? b. Is it a manual or automated lock? c. How old is the lock? d. -

How Barriers Shape Freshwater Fish Distributions: a Species Distribution Model Approach

1 How barriers shape freshwater fish distributions: a species distribution model approach 2 3 Mathias Kuemmerlen1* [email protected] 4 Stefan Stoll1,2 [email protected] 5 Peter Haase1,3 [email protected] 6 7 1Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum Frankfurt, Department of River 8 Ecology and Conservation, Clamecystr. 12, D-63571 Gelnhausen, Germany 9 2University of Koblenz-Landau, Institute for Environmental Sciences, Fortstr. 7, 76829 Landau, 10 Germany 11 3University of Duisburg-Essen, Faculty of Biology, Essen, Germany 12 *Corresponding author: Tel: +49 6051-61954-3120 13 Fax: +49 6051-61954-3118 14 15 Running title: How barriers shape fish distributions 16 17 Word count main text = 4679 18 1 PeerJ Preprints | https://doi.org/10.7287/peerj.preprints.2112v2 | CC BY 4.0 Open Access | rec: 18 Aug 2016, publ: 18 Aug 2016 19 Abstract 20 Aim 21 Barriers continue to be built globally despite their well-known negative effects on freshwater 22 ecosystems. Fish habitats are disturbed by barriers and the connectivity in the stream network 23 reduced. We implemented and assessed the use of barrier data, including their size and 24 magnitude, in distribution predictions for 20 species of freshwater fish to understand the 25 impacts on freshwater fish distributions. 26 27 Location 28 Central Germany 29 30 Methods 31 Obstruction metrics were calculated from barrier data in three different spatial contexts 32 relevant to fish migration and dispersal: upstream, downstream and along 10km of stream 33 network. The metrics were included in a species distribution model and compared to a model 34 without them, to reveal how barriers influence the distribution patterns of fish species. -

Life-History Traits Correlate with Temporal Trends in Freshwater Fish

Life-history traits correlate with temporal trends in freshwater fish populations for common European species Rafael Santos, Besnard Aurélien, Raphaël Santos, Nicolas Poulet, Aurélien Besnard To cite this version: Rafael Santos, Besnard Aurélien, Raphaël Santos, Nicolas Poulet, Aurélien Besnard. Life-history traits correlate with temporal trends in freshwater fish populations for common European species. Freshwater Biology, Wiley, 2021, 66 (2), pp.317-331. 10.1111/fwb.13640. hal-03177433 HAL Id: hal-03177433 https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-03177433 Submitted on 23 Mar 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Received: 28 October 2019 | Revised: 23 September 2020 | Accepted: 29 September 2020 DOI: 10.1111/fwb.13640 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Life-history traits correlate with temporal trends in freshwater fish populations for common European species Raphaël Santos1,2 | Nicolas Poulet3 | Aurélien Besnard1 1EPHE, PSL Research University, CNRS, INRA, UMR 5175 CEFE, Montpellier, France Abstract 2HES-SO / HEPIA, University of Applied 1. Understanding the population dynamics of aquatic species and how inter-specific Sciences and Arts of Western Switzerland, variation in demographic and life history traits influence population dynamics is cru- Ecology and Engineering of Aquatic Systems Research Group, Jussy, Switzerland cial to define their conservation status and design appropriate protection measures. -

Abbeyshrule, Co. Longford Unique ID

Location: Abbeyshrule, Co. Longford Unique ID: 260,446 (from PFRA database) Initial OPW Designation APSR AFRR IRR Co-ordinates Easting: 223,250 Northing: 260,250 River / Catchment / Sub-catchment River Inny / Owenacharra River / River Shannon (Lough Ree) Type of Flooding / Flood Risk Fluvial non-tidal Fluvial tidal Coastal (identify all that apply) Stage 1: Desktop Review River Flow Path 1.1 Flood History The River Inny flows through the township of Abbeyshrule on the eastern (include review of town boundary whilst the Royal Canal forms the perimeter on the western Floodmaps.ie) side. The village has a canal harbour with a boat slip. Flood Event Records There are no records of flood events for Abbeyshrule on floodmaps.ie. PFRA database comments (in italics) : 1.2 Relevant information on OPW comments flooding issues from Designated APSR on the basis of predictive analysis. OPW and LA staff LA comments Inny Abbeyshrule - Potentially due to new development – twenty houses. Questioned the extent shown in the PFRA maps. Possibly not the experience but not to be ruled out. Should be compared to 2009 flood extent. Farmland. Meeting / discussion summary comments: OPW comments • There are no flood risk issues that they are aware of. • The land downstream is low and acts as floodplain. • New houses near the church may be at risk. • The airfield is not known to be at significant risk. LA comments • Farmland flooded during the November 2009 event. • A public water supply intake is located upstream of the village; this is the source for the regional water supply. • The airfield was just about operational during the 2009 floods. -

Leuciscus Cephalus

ne Risk Assessment of Leuciscus cephalus Name of Organism: Leuciscus cephalus Linnaeus 1758 – Chub Objective: Assess the risks associated with this species in Ireland Version: Final 15/09/2014 Author(s) Michael Millane and Joe Caffrey Expert reviewer Rob Britton Stage 1 - Organism Information Stage 2 - Detailed Assessment Section A - Entry Section B - Establishment Section C - Spread Section D - Impact Section E - Conclusion Section F - Additional Questions About the risk assessment This risk assessment is based on the Non-native species AP plication based Risk Analysis (NAPRA) tool (version 2.66). NAPRA is a computer based tool for undertaking risk assessment of any non- native species. It was developed by the European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organisation (EPPO) and adapted for Ireland and Northern Ireland by Invasive Species Ireland. It is based on the Computer Aided Pest Risk Analysis (CAPRA) software package which is a similar tool used by EPPO for risk assessment. Notes: Confidence is rated as low, medium, high or very high. Likelihood is rated as very unlikely, unlikely, moderately likely, likely or very likely. The percentage categories are 0% - 10%, 11% - 33%, 34% - 67%, 68% - 90% or 91% - 100%. N/A = not applicable. This is a joint project by Inland Fisheries Ireland and the National Biodiversity Data Centre to inform risk assessments of non-native species for the European Communities (Birds and Natural Habitats) Regulations 2011. It is supported by the National Parks and Wildlife Service. Page 1 of 23 DOCUMENT CONTROL SHEET Risk Assessment of Leuciscus cephalus Name of Document: Dr Michael Millane and Dr Joe Caffrey Author (s): Dr Joe Caffrey Authorised Officer: Non-native species risk assessment Description of Content: Dr Cathal Gallagher Approved by: 15/09/2014 Date of Approval: n/a Assigned review period: n/a Date of next review: n/a Document Code List of No. -

A Continental-Scale Analysis of Fish Assemblage Functional Structure in European Rivers Maxime Logez, Pierre Bady, Andreas Melcher, Didier Pont

A continental-scale analysis of fish assemblage functional structure in European rivers Maxime Logez, Pierre Bady, Andreas Melcher, Didier Pont To cite this version: Maxime Logez, Pierre Bady, Andreas Melcher, Didier Pont. A continental-scale analysis of fish assemblage functional structure in European rivers. Ecography, Wiley, 2013, 36 (1), pp.80-91. 10.1111/j.1600-0587.2012.07447.x. hal-00835204 HAL Id: hal-00835204 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00835204 Submitted on 18 Jun 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. A continental-scale analysis of fish assemblage functional structure in European rivers Maxime Logez*, Pierre Bady†‡, Andreas Melcher◊ and Didier Pont*. * Irstea, UR HBAN, 1 rue Pierre-Gilles de Gennes - CS 10030, F-92761 Antony, France. † University Hospital (CHUV), Rue du Bugnon, 46, 1011 Lausanne, Switzerland. ‡ Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics, Bioinformatics Core Facility, Quartier UNIL-Sorge Bâtiment Génopode, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland ◊ Department of Water, Atmosphere and Environment, Institute of Hydrobiology and Aquatic Ecosystem Management, University of Natural Resources and Applied Life Sciences, Max-Emanuel-Strasse 17, 1180 Vienna, Austria. Correspondence: Maxime Logez Address: Irstea, UR HBAN, 1 rue Pierre-Gilles de Gennes - CS 10030, F-92761 Antony, France. -

Worldwide Status of Burbot and Conservation Measures

F I S H and F I S H E R I E S , 2010, 11, 34–56 Worldwide status of burbot and conservation measures Martin A Stapanian1, Vaughn L Paragamian2, Charles P Madenjian3, James R Jackson4, Jyrki Lappalainen5, Matthew J Evenson6 & Matthew D Neufeld7 1U. S. Geological Survey, Great Lakes Science Center, Lake Erie Biological Station, 6100 Columbus Avenue, Sandusky, OH 44870, USA; 2Idaho Department of Fish and Game, 2885 W. Kathleen Avenue, Coeur d’Alene, ID 83815, USA; 3U.S. Geological Survey, Great Lakes Science Center, 1451 Green Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48105, USA; 4Department of Natural Resources, Cornell Biological Field Station, 900 Shackelton Point Road, Bridgeport, NY 13030, USA; 5Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences, P.O. Box 65, University of Helsinki, Helsinki FIN-00014, Finland; 6Alaska Department of Fish and Game, 1300 College Road, Fairbanks, AK 99701-1551, USA; 7BC Ministry of Environment, #401-333 Victoria Street, Nelson, BC, Canada V1L 4K3 Abstract Correspondence: Although burbot (Lota lota Gadidae) are widespread and abundant throughout much Martin A Stapanian, U. S. Geological of their natural range, there are many populations that have been extirpated, Survey, Great Lakes endangered or are in serious decline. Due in part to the species’ lack of popularity as a Science Center, Lake game and commercial fish, few regions consider burbot in management plans. We Erie Biological review the worldwide population status of burbot and synthesize reasons why some Station, 6100 burbot populations are endangered or declining, some burbot populations have Columbus Avenue, Sandusky, OH 44870, recovered and some burbot populations do not recover despite management USA measures. -

The Inland Waterways of Ireland 1St Edition 2002 ISBN 085288 424 9

The Inland Waterways of Ireland 1st Edition 2002 ISBN 085288 424 9 Supplement No.1 Supplement Date: February 2011 This replaces all previous supplements Caution Erne Charter Boat Association www.boat-holidays.com Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of this supplement. It contains selected information and thus is Royal Canal Amenity Group www.royalcanal.net not definitive and does not include all known information River Bann and Lough Neagh Association on the subject in hand; this is particularly relevant to the http://riverbannloughneagh.org plans, which should not be used for navigation. The Tourism Ireland www.discoverireland.com author and Imray Laurie Norie and Wilson Ltd believe that Northern Ireland its selection is a useful aid to prudent navigation, but the www.discovernorthernireland.com safety of a vessel depends ultimately on the judgement of Afloat magazine www.afloat.ie the navigator, who should assess all information, National Trust www.nationaltrust.org.uk published or unpublished, available to him. Sustrans www.sustrans.org.uk This supplement contains amendments and corrections sent in by cruising yachtsmen and women. The updating Restorations and new projects of cruising guides is an ongoing process and the publisher Royal Canal is always glad to receive information, sketch charts or photographs for incorporation in future supplements or On 1st October 2010 the Royal Canal was opened through new editions. to Richmond Harbour in Co. Longford and so access to the Shannon was re-established for the first time in over 50 Note where lights have been modified in this text do please years. -

Wild Salmon and Sea Trout Catch Statistics Report

TABLE OF CONTENTS Chairman’s Statement 2 The Central and Regional Fisheries Boards 3 Introduction 4 Chapter 1 Summary Commercial and Angling Catch Statistics 2001 - 2009 5 Chapter 2 Summary Commercial Catch Statistics 2001 - 2009 8 Chapter 3 Summary Angling Catch Statistics 2001 - 2009 11 Chapter 4 Commercial and Angling Catch Tables 2009 16 Chapter 5 Commercial Catch Tables 2009 20 Chapter 6 Angling Catch Tables 2009 26 Chapter 7 Angling Catch Graphs and Charts 2009 58 Appendix i Map of Districts, Open, Catch and Release, and Closed Rivers 2009 70 Appendix ii Legislation 72 Appendix iii References 73 Appendix iv Glossary of Terms used in Report 74 1 CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT I am delighted to present the 2009 Wild Salmon and Sea Trout Fisheries Statistics Report. This annual report maps trends in the stocks of salmon and sea trout since 2001 from both the commercial and recreational fisheries sectors. This report provides valuable information to fisheries’ managers, scientists, policy makers and legislators and assists in the design and implementation of policies and strategies for the conservation of salmon and sea trout stocks in Ireland. The 2009 statistics show that the total number of salmon harvested by all methods was 24,278 – which represent a decrease of 22% on the total harvest recorded in 2008 . 2009 proved a difficult year for both anglers and commercial fishermen with the deterioration in catches due to unfavourable fishing conditions, high water levels, marine survival rates and some late fish runs at key fishing periods. The 2009 commercial catch was 6,757 salmon and 45 sea trout (over 40 cm) which was only 37% of the Total Allowable Catch (TAC) allocated to the sector.