Chub (Leuciscus Cephalus): a New Potentially Invasive Fish Species in Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISFC Annual Report 1999

1999 Salmon, Sea Trout . 3 Location Map for Awards Presentation in Doyle Burlington Brown Trout (Lake) . 4 Brown Trout (River) . 5 Bream . 6 Pike (Lake), Pike (River) . 8 Carp . 10 Eel, Roach/Bream Hybrid . 11 Rudd/Bream Hybrid, Perch . .12 Tench . 13 Bass . 14 Coalfish, Cod, Conger Eel, Dab, Greater Spotted Dogfish . 15 Lesser Spotted Dogfish, Spur Dogfish . 16 Flounder, Garfish, Grey Gurnard . 17 Red Gurnard, Tub Gurnard, Ling . 18 Mackerel . 19 Grey Mullet, Plaice . 20 ONTENTS Pollack, Pouting . 21 Blonde Ray, Homelyn Ray, Painted Ray . 22 Sting Ray, Three Bearded Rockling, Twaite Shad . 24 C Blue Shark . 25 Tope, Torsk, Ballan Wrasse, Cuckoo Wrasse . 26 New Records, Ten Species Award, Ten Pin Awards, Special Award for Juveniles, The Minister’s Award, . .27 Revised Specimen Weight/New Class, Special Notice, Limitation on Number of Claims, Exclusion from Specimen Status, Weighing of Fish, Metrification . 28 Common Skate, Captors Addresses, Distribution of Specimen Awards . .29 Acknowledgements, Presentation of Awards 1998, Fund Raising . 30 Accounts, Donations . 31 Use of the information contained in this report for press articles Balance Sheet . 32 and publicity is encouraged. It may be quoted without charge, Irish Record Fish Listing . 33 provided the source is acknowledged. Schedule of Specimen Weights (Revised) . 35 The report is copyright and prior permission to reproduce the Rules . 37 data for any other purpose other than reasonable review or Weighing Scale Certification – List of Centres . .40 analysis must be obtained in writing from the Irish Specimen Fish “Read it Carefully” by Des Brennan . 42 Committee. “Maybe we’ll stay at home this year!” by Derek Evans . -

EREP 2017 Annual Report

EREP 2017 Annual Report Inland Fisheries Ireland & the Office of Public Works Environmental River Enhancement Programme Acknowledgments The assistance and support of OPW staff, of all grades, from each of the three Drainage Maintenance Regions is gratefully appreciated. The support provided by regional IFI officers, in respect of site inspections and follow up visits and assistance with electrofishing surveys is also acknowledged. Overland access was kindly provided by landowners in a range of channels and across a range of OPW drainage schemes. Project Personnel Members of the EREP team include: Dr. James King Brian Coghlan MSc (Res) Amy McCollom IFI Report Number: IFI/2018/1-4430 CITATION: Coghlan, B., McCollom, A., and King, J.J. (2018) Environmental River Enhancement Programme Summary Report 2017. Inland Fisheries Ireland, 3044 Lake Drive, Citywest, Dublin 24, Ireland. © Inland Fisheries Ireland 2018 The report includes Ordnance Survey Ireland data reproduced under OSi Copyright Permit No. MP 007508. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Ordnance Survey Ireland and Government of Ireland copyright. © Ordnance Survey Ireland, 2016. Table of Contents 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 The Inny Survey Programme ..................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Long-term Monitoring ................................................................................................................ -

Spawning Strategies in Cypriniform Fishes in a Lowland River Invaded By

Hydrobiologia (2020) 847:4031–4047 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-020-04394-9 (0123456789().,-volV)( 0123456789().,-volV) PRIMARY RESEARCH PAPER Spawning strategies in cypriniform fishes in a lowland river invaded by non-indigenous European barbel Barbus barbus Catherine Gutmann Roberts . J. Robert Britton Received: 15 May 2020 / Revised: 11 August 2020 / Accepted: 23 August 2020 / Published online: 4 September 2020 Ó The Author(s) 2020 Abstract Spawning strategies of lowland river remained relatively small by the end of their growth fishes include single spawning, where reproduction season (October). For dace Leuciscus leuciscus, only generally occurs in early spring to provide 0? fish single spawning events were evident, but with 0? dace with an extended growth season through the summer, always being relatively large. Therefore, multiple but with a high risk of stochastic mortality events spawning appears to be a common strategy that occurring, such as early summer floods. This risk can provides resilience in 0? fish against stochastic be reduced by multiple or protracted spawning strate- mortality events in lowland rivers. gies, where 0? fish are produced over an extended period, often into mid-summer, but with the trade-off Keywords Spawning strategies Á Invasion biology Á being a shorter growth season. The spawning strate- Recruitment Á Cypriniform Á Barbus gies of cypriniform fish were explored in the River Teme, a spate river in Western England, which has non-indigenous European barbel Barbus barbus pre- sent. Sampling 0? fish in spring and summer and Introduction across three spawning periods, B. barbus, chub Squalius cephalus and minnow Phoxinus phoxinus In temperate lowland rivers, larval and juvenile fish in always revealed multiple spawning events, with 0? their first year of life (‘0?’) may face episodic flood fish of \ 20 mm present in samples collected from events that can be deleterious to their cohorts, June to August. -

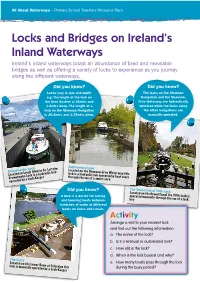

Locks and Bridges on Ireland's Inland Waterways an Abundance of Fixed

ack eachers Resource P ways – Primary School T All About Water Locks and Bridges on Ireland’s Inland Waterways Ireland’s inland waterways boast an abundance of fixed and moveable bridges as well as offering a variety of locks to experience as you journey along the different waterways. Did you know? Did you know? The locks on the Shannon Navigation and the Shannon- Locks vary in size and depth Erne Waterway are hydraulically e.g. the length of the lock on operated while the locks along the Erne System is 36mtrs and the other navigations are 1.2mtrs deep. The length of a manually operated. lock on the Shannon Navigation is 29.2mtrs and 1.35mtrs deep. Ballinamore Lock im aterway this Lock . Leitr Located on the Shannon-Erne W n in Co ck raulic lock operated by boat users gh Alle ulic lo lock is a hyd Drumshanbon Lou ydra ugh the use of a smart card cated o ock is a h thro Lo anbo L eeper rumsh ock-K D ed by a L operat The Grand Canal 30th Lock Did you know? Located on the Grand Canal the 30th Lock is operated manually through the use of a lock A lock is a device for raising key and lowering boats between stretches of water of different levels on rivers and canals. Activity Arrange a visit to your nearest lock and find out the following information: a. The name of the lock? b. Is it a manual or automated lock? c. How old is the lock? d. -

How Barriers Shape Freshwater Fish Distributions: a Species Distribution Model Approach

1 How barriers shape freshwater fish distributions: a species distribution model approach 2 3 Mathias Kuemmerlen1* [email protected] 4 Stefan Stoll1,2 [email protected] 5 Peter Haase1,3 [email protected] 6 7 1Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum Frankfurt, Department of River 8 Ecology and Conservation, Clamecystr. 12, D-63571 Gelnhausen, Germany 9 2University of Koblenz-Landau, Institute for Environmental Sciences, Fortstr. 7, 76829 Landau, 10 Germany 11 3University of Duisburg-Essen, Faculty of Biology, Essen, Germany 12 *Corresponding author: Tel: +49 6051-61954-3120 13 Fax: +49 6051-61954-3118 14 15 Running title: How barriers shape fish distributions 16 17 Word count main text = 4679 18 1 PeerJ Preprints | https://doi.org/10.7287/peerj.preprints.2112v2 | CC BY 4.0 Open Access | rec: 18 Aug 2016, publ: 18 Aug 2016 19 Abstract 20 Aim 21 Barriers continue to be built globally despite their well-known negative effects on freshwater 22 ecosystems. Fish habitats are disturbed by barriers and the connectivity in the stream network 23 reduced. We implemented and assessed the use of barrier data, including their size and 24 magnitude, in distribution predictions for 20 species of freshwater fish to understand the 25 impacts on freshwater fish distributions. 26 27 Location 28 Central Germany 29 30 Methods 31 Obstruction metrics were calculated from barrier data in three different spatial contexts 32 relevant to fish migration and dispersal: upstream, downstream and along 10km of stream 33 network. The metrics were included in a species distribution model and compared to a model 34 without them, to reveal how barriers influence the distribution patterns of fish species. -

Life-History Traits Correlate with Temporal Trends in Freshwater Fish

Life-history traits correlate with temporal trends in freshwater fish populations for common European species Rafael Santos, Besnard Aurélien, Raphaël Santos, Nicolas Poulet, Aurélien Besnard To cite this version: Rafael Santos, Besnard Aurélien, Raphaël Santos, Nicolas Poulet, Aurélien Besnard. Life-history traits correlate with temporal trends in freshwater fish populations for common European species. Freshwater Biology, Wiley, 2021, 66 (2), pp.317-331. 10.1111/fwb.13640. hal-03177433 HAL Id: hal-03177433 https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-03177433 Submitted on 23 Mar 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Received: 28 October 2019 | Revised: 23 September 2020 | Accepted: 29 September 2020 DOI: 10.1111/fwb.13640 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Life-history traits correlate with temporal trends in freshwater fish populations for common European species Raphaël Santos1,2 | Nicolas Poulet3 | Aurélien Besnard1 1EPHE, PSL Research University, CNRS, INRA, UMR 5175 CEFE, Montpellier, France Abstract 2HES-SO / HEPIA, University of Applied 1. Understanding the population dynamics of aquatic species and how inter-specific Sciences and Arts of Western Switzerland, variation in demographic and life history traits influence population dynamics is cru- Ecology and Engineering of Aquatic Systems Research Group, Jussy, Switzerland cial to define their conservation status and design appropriate protection measures. -

Underwater Observation and Habitat Utilization of Three Rare Darters

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2010 Underwater observation and habitat utilization of three rare darters (Etheostoma cinereum, Percina burtoni, and Percina williamsi) in the Little River, Blount County, Tennessee Robert Trenton Jett University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Natural Resources and Conservation Commons Recommended Citation Jett, Robert Trenton, "Underwater observation and habitat utilization of three rare darters (Etheostoma cinereum, Percina burtoni, and Percina williamsi) in the Little River, Blount County, Tennessee. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2010. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/636 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Robert Trenton Jett entitled "Underwater observation and habitat utilization of three rare darters (Etheostoma cinereum, Percina burtoni, and Percina williamsi) in the Little River, Blount County, Tennessee." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Wildlife and Fisheries Science. James L. Wilson, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: David A. Etnier, Jason G. -

Affect Space Use by Warpaint Shiners (Luxilus Coccogenis)

Received: 26 February 2018 | Revised: 16 July 2018 | Accepted: 19 July 2018 DOI: 10.1111/eff.12440 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Stocked rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) affect space use by Warpaint Shiners (Luxilus coccogenis) Duncan Elkins | Nathan P. Nibbelink | Gary D. Grossman Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources, University of Georgia, Athens, Abstract Georgia Due to widespread stocking, Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss Walbaum) are per- Correspondence haps the most widely distributed invasive species in the world. Nonetheless, little is Gary D. Grossman, Warnell School of known about the effects of stocked Rainbow Trout on native non- game species. We Forestry & Natural Resources, University of Georgia, Athens, GA. conducted experiments in an artificial stream to assess the effects of hatchery Email: [email protected] Rainbow Trout on home range and behaviour of Warpaint Shiners (Luxilus coccogenis Funding information Cope), a common minnow frequently found in stocked Southern Appalachian Georgia Department of Natural Resources, streams. We used the LoCoH algorithm to generate polygons describing the home Grant/Award Number: 2021RR272; Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources; ranges used by Warpaint Shiners. When a stocked trout was present Warpaint USDA McIntire-Stennis Program, Grant/ Shiners: (a) increased home range size by 57%, (b) were displaced into higher velocity Award Number: GEOZ-0176-MS Grossman mesohabitats, and (c) reduced mean overlap between the home ranges of individual warpaint shiners. Rainbow Trout did not significantly affect the edge/area ratio of Warpaint Shiner home ranges. Warpaint Shiner density (two and five fish treatments) did not significantly affect any response variable. Displacement from preferred mi- crohabitats and increases in home range size likely result in increased energy ex- penditure and exposure to potential predators (i.e., decreased individual fitness) of Warpaint Shiners when stocked trout are present. -

Abbeyshrule, Co. Longford Unique ID

Location: Abbeyshrule, Co. Longford Unique ID: 260,446 (from PFRA database) Initial OPW Designation APSR AFRR IRR Co-ordinates Easting: 223,250 Northing: 260,250 River / Catchment / Sub-catchment River Inny / Owenacharra River / River Shannon (Lough Ree) Type of Flooding / Flood Risk Fluvial non-tidal Fluvial tidal Coastal (identify all that apply) Stage 1: Desktop Review River Flow Path 1.1 Flood History The River Inny flows through the township of Abbeyshrule on the eastern (include review of town boundary whilst the Royal Canal forms the perimeter on the western Floodmaps.ie) side. The village has a canal harbour with a boat slip. Flood Event Records There are no records of flood events for Abbeyshrule on floodmaps.ie. PFRA database comments (in italics) : 1.2 Relevant information on OPW comments flooding issues from Designated APSR on the basis of predictive analysis. OPW and LA staff LA comments Inny Abbeyshrule - Potentially due to new development – twenty houses. Questioned the extent shown in the PFRA maps. Possibly not the experience but not to be ruled out. Should be compared to 2009 flood extent. Farmland. Meeting / discussion summary comments: OPW comments • There are no flood risk issues that they are aware of. • The land downstream is low and acts as floodplain. • New houses near the church may be at risk. • The airfield is not known to be at significant risk. LA comments • Farmland flooded during the November 2009 event. • A public water supply intake is located upstream of the village; this is the source for the regional water supply. • The airfield was just about operational during the 2009 floods. -

Aquatic Biota

Low Gradient, Cool, Headwaters and Creeks Macrogroup: Headwaters and Creeks Shawsheen River, © John Phelan Ecologist or State Fish Game Agency for more information about this habitat. This map is based on a model and has had little field-checking. Contact your State Natural Heritage Description: Cool, slow-moving, headwaters and creeks of low-moderate elevation flat, marshy settings. These small streams of moderate to low elevations occur on flats or very gentle slopes in watersheds less than 39 sq.mi in size. The cool slow-moving waters may have high turbidity and be somewhat poorly oxygenated. Instream habitats are dominated by glide-pool and ripple-dune systems with runs interspersed by pools and a few short or no distinct riffles. Bed materials are predominenly sands, silt, and only isolated amounts of gravel. These low-gradient streams may have high sinuosity but are usually only slightly entrenched with adjacent Source: 1:100k NHD+ (USGS 2006), >= 1 sq.mi. drainage area floodplain and riparian wetland ecosystems. Cool water State Distribution:CT, ME, MD, MA, NH, NJ, NY, PA, RI, VT, VA, temperatures in these streams means the fish community WV contains a higher proportion of cool and warm water species relative to coldwater species. Additional variation in the stream Total Habitat (mi): 16,579 biological community is associated with acidic, calcareous, and neutral geologic settings where the pH of the water will limit the % Conserved: 11.5 Unit = Acres of 100m Riparian Buffer distribution of certain macroinvertebrates, plants, and other aquatic biota. The habitat can be further subdivided into 1) State State Miles of Acres Acres Total Acres headwaters that drain watersheds less than 4 sq.mi, and have an Habitat % Habitat GAP 1 - 2 GAP 3 Unsecured average bankfull width of 16 feet or 2) Creeks that include larger NY 41 6830 94 325 4726 streams with watersheds up to 39 sq.mi. -

Leuciscus Cephalus

ne Risk Assessment of Leuciscus cephalus Name of Organism: Leuciscus cephalus Linnaeus 1758 – Chub Objective: Assess the risks associated with this species in Ireland Version: Final 15/09/2014 Author(s) Michael Millane and Joe Caffrey Expert reviewer Rob Britton Stage 1 - Organism Information Stage 2 - Detailed Assessment Section A - Entry Section B - Establishment Section C - Spread Section D - Impact Section E - Conclusion Section F - Additional Questions About the risk assessment This risk assessment is based on the Non-native species AP plication based Risk Analysis (NAPRA) tool (version 2.66). NAPRA is a computer based tool for undertaking risk assessment of any non- native species. It was developed by the European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organisation (EPPO) and adapted for Ireland and Northern Ireland by Invasive Species Ireland. It is based on the Computer Aided Pest Risk Analysis (CAPRA) software package which is a similar tool used by EPPO for risk assessment. Notes: Confidence is rated as low, medium, high or very high. Likelihood is rated as very unlikely, unlikely, moderately likely, likely or very likely. The percentage categories are 0% - 10%, 11% - 33%, 34% - 67%, 68% - 90% or 91% - 100%. N/A = not applicable. This is a joint project by Inland Fisheries Ireland and the National Biodiversity Data Centre to inform risk assessments of non-native species for the European Communities (Birds and Natural Habitats) Regulations 2011. It is supported by the National Parks and Wildlife Service. Page 1 of 23 DOCUMENT CONTROL SHEET Risk Assessment of Leuciscus cephalus Name of Document: Dr Michael Millane and Dr Joe Caffrey Author (s): Dr Joe Caffrey Authorised Officer: Non-native species risk assessment Description of Content: Dr Cathal Gallagher Approved by: 15/09/2014 Date of Approval: n/a Assigned review period: n/a Date of next review: n/a Document Code List of No. -

![Kyfishid[1].Pdf](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2624/kyfishid-1-pdf-1462624.webp)

Kyfishid[1].Pdf

Kentucky Fishes Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources Kentucky Fish & Wildlife’s Mission To conserve, protect and enhance Kentucky’s fish and wildlife resources and provide outstanding opportunities for hunting, fishing, trapping, boating, shooting sports, wildlife viewing, and related activities. Federal Aid Project funded by your purchase of fishing equipment and motor boat fuels Kentucky Department of Fish & Wildlife Resources #1 Sportsman’s Lane, Frankfort, KY 40601 1-800-858-1549 • fw.ky.gov Kentucky Fish & Wildlife’s Mission Kentucky Fishes by Matthew R. Thomas Fisheries Program Coordinator 2011 (Third edition, 2021) Kentucky Department of Fish & Wildlife Resources Division of Fisheries Cover paintings by Rick Hill • Publication design by Adrienne Yancy Preface entucky is home to a total of 245 native fish species with an additional 24 that have been introduced either intentionally (i.e., for sport) or accidentally. Within Kthe United States, Kentucky’s native freshwater fish diversity is exceeded only by Alabama and Tennessee. This high diversity of native fishes corresponds to an abun- dance of water bodies and wide variety of aquatic habitats across the state – from swift upland streams to large sluggish rivers, oxbow lakes, and wetlands. Approximately 25 species are most frequently caught by anglers either for sport or food. Many of these species occur in streams and rivers statewide, while several are routinely stocked in public and private water bodies across the state, especially ponds and reservoirs. The largest proportion of Kentucky’s fish fauna (80%) includes darters, minnows, suckers, madtoms, smaller sunfishes, and other groups (e.g., lam- preys) that are rarely seen by most people.