"The Bishop's Ministers":The Office of Coroner in Late Medieval Durham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

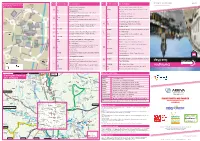

Darlington Borough Local Plan Policies Maps

Darlington Borough Local Plan Policies Maps Darlington Borough Council June 2018 Contents Map 1 Key Diagram Map 2 Borough Overview Map 3 West side of the Borough Map 4 East side of the Borough Map 5 Town Overview Map 6 North West of the Town Map 7 North East of the Town Map 8 South East of the Town Map 9 South West of the Town Map 10 Town Centre Map 11 Heighington Map 12 Hurworth Map 13 Middleton St George Map 14 Sadberge, Bishopton, Brafferton and Neasham Map 15 Low Coniscliffe, Merrybent, High Coniscliffe and Piercebridge Key Æb A6072 Æb Map 1 A68 Æb Heighington B6275 Bishopton Brafferton A167 B6279 A1 (M) Sadberge A66 A67 A66 High North Road Piercebridge Coniscliffe Railway Station Æb Merrybent Æb Darlington Railway Station Æb Low Dinsdale Railway A67 Teesside Airport Coniscliffe Station Æb Railway Station Middleton Main Urban Area (SH 1) St George Durham Tees Valley Airport Z (! Service Villages (SH 1) A66 e Rural Villages (SH 1) (! A167 Strategic Housing Locations (H 2) Mixed Strategic Use (H 11) & (E 2) Strategic Employment Sites (E 1) & (E 2) Hurworth Neasham Town Centre Fringe (TC 6) Proposed Strategic Green Infrastructure Corridors (EN 3) & (EN 4) & (EN 7) Existing Strategic Green Infrastructure Corridors (EN 3) & (EN 4) & (EN 7) Strategic Highway Link Northern Link Road Potential Routes (IN 1) (H 10) New Road & Public Transport Links (IN 1) Key Road Network (IN 1) Key Public Transport Corridors (IN 1) Z Durham Tees Valley Airport bÆ Rail Stations Darlington Borough Boundary Main Roads Railway Line Rivers Map 2 Map 3 Map 4 Map -

The Stocktonian Year Book

THE STOCKTONIAN YEAR BOOK 1950-51 HOT F.;: ;--R/AT THE STOCKTONIAN YEAR BOOK % 1950-51 Bilhnjum Press Limited, Press Buildings, Rillm^h^m. (So, Durham. 1951 OLD STOCKTONIANS' ASSOCIATION. Founded 1913 An Association of Old Boys of the Grangefield Grammar School, Stockton-on-Tees, formerly known as the Stockton Secondary School for Boys, and originally as the Stockton Higher Grade School. Annual Subscription: 2/-. Annual Subscription from those who left 1949-1951: 1/-. Life Subscription: 25/-. All communications should be addressed to the Hon. Secretary, Old Stocktonians' Association. Grangefield Grammar School for Boys, Stockton-on-Tees. 2 List of Officials for 1951-52 Presidents: G. D LITTLE. Esq.. Dr. J. R. KINNES. M.A.. Ph.D., E. BALDWIN. Esq.. O.B.E.. M.Ed. Vice-Presidents: N. E. Green. Esq. H. D. Hardie. Esq. D. Shepherd. Esq. Councillor E. H. Brown. L Bell. Esq.. A.I.I.A. A.M.I.P.E. J. Wilkinson. Esq . F.C.C.S. F.H.A. Committee: R. Beaumont, Esq. S. V. Morris, Esq.. M.A. T. H. Bulmer. Esq. W. H. Munday. Esq.. B.A. V. E. Cable. Esq.. B.A. W B. Readman, Esq. K. Dodsworth, Esq. G. M. W. Scott. Esq. j. Gill. Esq. J. Short, Esq. D. W. Henderson, Esq. G. Claxton Smith. Esq. I Howden, Esq. G. Stott. Esq. T. L. James. Esq. R. B. Wright. Esq.. B.A. Hon. Auditor: N. E. Green, Esq. Hon. Treasurer: H. Nicholson. Esq.. M.Sc. Hon. Secretary: T. B. Brooke. Esq., M.A. Trustees of Benevolent Fund: N. E. Green. -

Barney Connect Issue 01 Alan Spring 2014 Stevens

RECONNECTING Inside THE BARNARDIAN 16 BARNARDIAN WEEKEND 2014 18 OB RUGBY RETURNS COMMUNITY 22 DATES FOR THE DIARY 24 REMEMBERING ALAN WILKINSON New OB website recently launched Page 19 ISSUE 01 BARNEY SPRING 2014 Magazine for Barnard Castle School CONNECT alumni and supporters IT’S ALL ABOUT BEING YOURSELF OB Spotlight: Rob Andrew MBE 2 ISSUE 01 Contact Welcome BARNEY CONNECT ISSUE 01 ALAN SPRING 2014 STEVENS Headmaster Barnard School Castle Alumni & Archive Recently I received a letter from Bruce Crawcour, an Old Barnardian Miss Dorothy Jones: in Shrewsbury, formerly of Durham House from 1958-1964. +44 (0)1833 696025 Enclosed with the letter was an aged and yellowing piece of paper [email protected] which dated from 1886. It was an original programme for the opening of the main school building which brought the School back to Barney from Published in partnership with Middleton-one-Row and situated it close to the decrepit medieval the Old Barnardians’ Club institution which gave it part of its foundation. On the cover of the programme, the School’s architect, Robert Johnson, had drawn a sketch of the front of the new building, but – with typical architect’s license – he had gone even further and had drawn something which did not even exist then. Just to the east of School House (what is now Brereton House and the Linen Room) he had drawn a Chapel. What he drew, however, was quite different in both style and orientation from what we have today. He drew a chapel in sympathy with All correspondence to be directed the design of the main building which appeared to have a belfry in the style through the OB Club Secretary of a pepperpot on its roof. -

Darlington Borough Council M3

This document was classified as: OFFICIAL Darlington Borough Council Hearing Statement April 2021 Matter 3 - Vision, aims, objectives and spatial strategy Presumption in favour of sustainable development (policy SD1) SQ3.1. Subject to the Council’s proposed modification, is policy SD1 consistent with national policy and would it be effective in helping decision makers know how to react to development proposals? Yes. Subject to the proposed modification, policy SD1 is consistent with national policy and would be effective in helping decision makers know how to react to development proposals. In the Council’s response to PQ11 it was acknowledged that there were inconsistencies with policy SD1 and paragraph 11 of the NPPF. The related paragraph to the presumption in favour of sustainable development was revised in the 2018 version of the NPPF and these changes were not reflected in policy SD1. Modifications are suggested to the policy to resolve these issues and ensure consistency with the framework. Although policy SD1 replicates parts of paragraph 11 of the NPPF the intention was to assist in making local communities, developers and stakeholders more aware of the presumption and how it is applied. The Council would however be open to further discussion on this policy. Settlement hierarchy (policy SH1) and the distribution of housing and employment development allocations Q3.2. Is the settlement hierarchy set out in policy SH1 based on evidence that is relevant, up to date, adequate and proportionate? Is the hierarchy and associated broad distribution of development reasonable, having regard to alternatives that were considered during the preparation of the Plan and the findings of the sustainability appraisal? With regards to the first part of the question; yes, it is considered that the settlement hierarchy set out in policy SH1 is based on evidence that is relevant, up to date, adequate and proportionate. -

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society Unwanted

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society baptism birth marriage No Gsurname Gforename Bsurname Bforename dayMonth year place death No Bsurname Bforename Gsurname Gforename dayMonth year place all No surname forename dayMonth year place Marriage 933ABBOT Mary ROBINSON James 18Oct1851 Windermere Westmorland Marriage 588ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul1869 Tynemouth Marriage 935ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 Jul1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland Marriage1561ABBS Maria FORDER James 21May1861 Brooke, Norfolk Marriage 1442 ABELL Thirza GUTTERIDGE Amos 3 Aug 1874 Eston Yorks Death 229 ADAM Ellen 9 Feb 1967 Newcastle upon Tyne Death 406 ADAMS Matilda 11 Oct 1931 Lanchester Co Durham Marriage 2326ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth SOMERSET Ernest Edward 26 Dec 1901 Heaton, Newcastle upon Tyne Marriage1768ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16Oct1849 Coughton Northampton Death 1556 ADAMS Thomas 15 Jan 1908 Brackley, Norhants,Oxford Bucks Birth 3605 ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth 18 May 1876 Stockton Co Durham Marriage 568 ADAMSON Annabell HADAWAY Thomas William 30 Sep 1885 Tynemouth Death 1999 ADAMSON Bryan 13 Aug 1972 Newcastle upon Tyne Birth 835 ADAMSON Constance 18 Oct 1850 Tynemouth Birth 3289ADAMSON Emma Jane 19Jun 1867Hamsterley Co Durham Marriage 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth Marriage1292ADAMSON Jane HARTBURN John 2Sep1839 Stockton & Sedgefield Co Durham Birth 3654 ADAMSON Julie Kristina 16 Dec 1971 Tynemouth, Northumberland Marriage 2357ADAMSON June PORTER William Sidney 1May 1980 North Tyneside East Death 747 ADAMSON -

The Thbsdali Mercury—Wednesday, March 24, 1880

THE THBSDALI MERCURY—WEDNESDAY, MARCH 24, 1880. DM- SOUTH DURHAM ELECTION, 1880. Green well, Thos. Wm., esq., F.R.8.L., Broomshields, Stephens, Rev. W. H. G, St. Jobn'i TO THE ELECTORS OF THE SOUTHERN most important questions which now engage pubhe attention. In the meantime, I venture to submit for Darlington DIVISION OF TOT COUNTY OF esq., Darlington-lane, Norton OLONEL SUBTREE'S CENTRAL Greenwell, Wot., esq., Job's Hill House, Crook DURHAM. your eoBMderetion, • brief itotememt of the views Stewart, Rev. John, Hart, Hartlepool COMMITTEE LISTS. Greeley, R. A D., esq., High Park, Droitwich which I entertain. C Stobart, H. B, esq, Wittoo Tower, Wittoo-le-Weer ENTLEMEN,—The approaching diMolution of The constituencies will shortly be called upon H StobeTt,W.C, *M^gp*Jlow Hill. Borobndg* HENRY EDWARD BCRTEES, Esq., Red worth, Parliament, and the political activity already to decide whether they approve or disapprove of the Hall, Colonel, Heighington, Darlington Btobbs, Hall, esq, Farnley, Willing*"- _ Hall, Darlington, CHAIUUV. Gawakened throughout the division, render it desirable manner in which the affairs of the country have, Hardinge, Sir Edward 8., Bart, Fowler's Park, Storehouse, Thomas, esq, Greatham, West Hartle Sir WILLIAM EDEN, Bart, Windleetone, that I ihould at once addrassyou. during the last six years, been administered by the Hawkhurst pool Cabinet of Lord Beacon.fleld. I will state shortly Vic* CHAIRMAIC, At the ensuing General Election I •ball once more Hardy, George, esq.. Lynn-street, West Hartlepool Storehouse, W, esq, Greatbam, West HarUepool the reasons for which I think that its continuance in place my political set view at your ditpoeal. -

Statement of Persons Nominated, Notice of Poll and Situation of Polling Stations

STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED, NOTICE OF POLL AND SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS Durham County Election of a Member of Parliament for Bishop Auckland Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of a Member of Parliament for Bishop Auckland will be held on Thursday 8 June 2017, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. One Member of Parliament is to be elected. 3. The names, home addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated for election and the names of all persons signing the Candidates nomination paper are as follows: Names of Signatories Names of Signatories Names of Signatories Name of Description (if Home Address Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Candidate any) Assentors Assentors Assentors ADAMS (address in the The Conservative McBain Trotter William K(++) Henderson Henderson (+) (++) Christopher Bishop Auckland Party Candidate Rupert J M(+) Jones Dorothy Edward(+) Christine(++) Fraser Constituency) Thompson Sheila Trotter Mary V McFarlane Alastair J Oxby Lynne Tyrrell Arthur R W Reay Gordon Stubbs Gladys Stubbs Peter L Tyrrell Helen D Simpson Vida M Rowlandson Souter Michael R Mitchell Kathleen M James M Colwill David S Souter Joanne E GOODMAN (address in the Labour Party Nicholson Henry(+) Kellett Marjorie(++) Tait Joanna E A(+) Madgwick (+) (++) Helen Catherine Bishop Auckland Hunt Philip J Allen Joy Fleming David A Alison E(++) Constituency) Foster Neil C Graham Barbara Hackworth-Young Cullen Jack Graham James V Yorke Robert J -

English Hundred-Names

l LUNDS UNIVERSITETS ARSSKRIFT. N. F. Avd. 1. Bd 30. Nr 1. ,~ ,j .11 . i ~ .l i THE jl; ENGLISH HUNDRED-NAMES BY oL 0 f S. AND ER SON , LUND PHINTED BY HAKAN DHLSSON I 934 The English Hundred-Names xvn It does not fall within the scope of the present study to enter on the details of the theories advanced; there are points that are still controversial, and some aspects of the question may repay further study. It is hoped that the etymological investigation of the hundred-names undertaken in the following pages will, Introduction. when completed, furnish a starting-point for the discussion of some of the problems connected with the origin of the hundred. 1. Scope and Aim. Terminology Discussed. The following chapters will be devoted to the discussion of some The local divisions known as hundreds though now practi aspects of the system as actually in existence, which have some cally obsolete played an important part in judicial administration bearing on the questions discussed in the etymological part, and in the Middle Ages. The hundredal system as a wbole is first to some general remarks on hundred-names and the like as shown in detail in Domesday - with the exception of some embodied in the material now collected. counties and smaller areas -- but is known to have existed about THE HUNDRED. a hundred and fifty years earlier. The hundred is mentioned in the laws of Edmund (940-6),' but no earlier evidence for its The hundred, it is generally admitted, is in theory at least a existence has been found. -

Darlington Bus

J l uly www.connectteesvalley.com Stand Service number Key destinations Stand Service number Key destinations together journey Let’s Railway Darlington Town Centre Gladstone Street Gladstone Street Bus Stands 9 Woodland Road, Branksome 8 Woodland Road, Shildon, Bishop Auckland : Woodland Road, Mowden 8B/X8 Woodland Road, Shildon, Bishop Auckland, Crook, A 8= Harrowgate Hill Tow Law 8= Hummersknott, Mowden, Faverdale, West Park J 9 Woodland Road, Branksome 9 Yarm Road, Lingfield Point, Red Hall : Woodland Road, Mowden :/:A Clifton Road, Skerne Park B 8@ Hollyhurst Road, Willow Road, Faverdale, West Park ; Corporation Road, Brinkburn Road, Bates Avenue, Minors Crescent 9 Yarm Road, Lingfield Point, Red Hall @ Darlington College, Haughton Road, Springfield K :B Hundens Lane, Albert Hill, North Road, C 87 Darlington College, Haughton Road, Whinfield Northwood Park 8:A/8:B Neasham Road, Firthmoor D 89/89A Yarm Road, Middleton St George, Middleton One Row, @ Darlington College, Haughton Road, Springfield Trees Park Village F L 87 Darlington College, Haughton Road, Whinfield X== Harrowgate Hill, Stockton, Middlesbrough G 8:A/8:B Neasham Road, Firthmoor X== Woodland Road, Faverdale :A Rise Carr, Harrowgate Hill, Harrowgate Farm 89/89A Hurworth Place, Hurworth </<A Harrowgate Hill, Newton Aycliffe, Shildon, :; Middleton Tyas, Catterick Village, Richmond Bishop Auckland >9 Hurworth Place, North & East Cowton, Brompton, > Harrowgate Hill, Newton Aycliffe, Ferryhill, Durham Northallerton ? Harrowgate Hill, Newton Aycliffe, Ferryhill, H M X></X>= -

Durham. (Kelly's

474 RCS DURHAM. (KELLY'S Russell Jas. 28 Buck la. Low fell,Gateshd Samuel Rev. George lii.A. Bridge street, Scott F. Melrose ho. Yarm rd. Stock ton Russell John, Carr's Hill ho. Gateshead Tow Law R.S.O Scott George, Laygate la. South Shields Russell John George, Prospect house, Samuelson Francis Arthur Edward, Scott Geo.7 Lorne ter. Yarm rd.Stockton Shincliffe, Durharn 1 Sockburn hall, Darlington Scott George, Newbottle, Fence Houses Russell Joseph R. 32 Queen's rd. Jarrow Sanders .Arthur, 2 Vane ter. Darlington Scott George,21Westbourne st. Stockton Russell Miss, 129Church st.nth.Sndrlnd SandersE. W.Kincora,Hartburn,Stocktn Scott Ueorge, 34 Whitehall rd.Gateshead Russell William, 223 .Albert rd. J arrow SandersU. W.3Lorne tar. Yarm rd.Stcktn Scott GeorgeHy.9Chester st.Sunderland Russell William, The Knoll, Coniscliffe Sanders I. 102 Northgate st. Hartlepool Scott Hy.44High Southwick,Sunderland road, Darlington Sanders J.J. Glenholme, Yarm rd.Stcktn Scott James, Hill crest, Ryton R.S.O Rust Charle8, 5 Hall terrace, Union Sanders Mrs. 3 Kepier terrace, Durham Scott John, 269 Alhertroad, Jarrow lane, Gateshead Sanderson A. lleaconsfield st. Hartlepool SC'ott John, Burnopfield R.S.O Rust John, 8 Suffolk street, Jarrow Sanderson Franl.'is, 7 Van Mildert ter- Scott John J.P. Ford hall, South Hylton, Rust Mrs. 61 Gilesgate, Durham race, Y arm road, Stock ton Sunderland RutherfordGeo.Carlton ter.Spennymoor Sanderson Frank, Springholm terrace, Scott John, High Coniscliffe, Darlington Rutherford John, 7 Peterbro' st. Gatshd Spring street, Stockton Scott John, 33 South Railway street, Rutherford John,sThe Royalty,Sndrlnd Sanderson G. -

NB: Some Products Have a Short Lead Time Built in to Help Us Meet Your Order

DOORSTEP DELIVERY AREAS... A family business delivering you Darlington Newton Aycliffe Northallerton Middleton St. George award-winning, organic dairy Richmond & most villages in-between produce with provenance. Barnard Castle Redworth Newton Aycliffe Heighington Aycliffe Bolam Village Ingleton Staindrop Stainton Village Sadberge Barnard Castle Gainford Walworth Winston Peircebridge Long Newton Whorlton Caldwell Darlington Manfield Middleton Saint George Croft-on-Tees Neaham Barningham Hurworth-on-Tees Newsham Barton Melsonby Dalton on Tees Dalton Ravensworth Gayles Middleton Gilling West Tyas Skeeby North Cowton Great Smeaton East Cowton Richmond Hutton Bonville Danby Wiske Brompton Northallerton HOW TO ORDER… We are proud to supply our local Online and enjoy flexibility to add eggs, cheese, community“ & passionate about sharing the milk, cream & butter up to 8pm the evening before benefits of dairy farming organically your delivery. Caroline Bell and brother Graham Tweddle” Register for your online account from our home of Acorn Dairy page www.acorndairy.co.uk NB: Some products have a short lead time built in to help us meet your order. Best Dairy Milk Brand 2020 To order via the office: T: 01325 466999 Garthorne Farm, Archdeacon Newton, E: [email protected] Darlington, Co. Durham DL2 2YB T: 01325 466999 Mon-Fri 8am- 4pm, Sat 8am-10.00am [email protected] Easy to set up & hassle-free. Please www.acorndairy.co.uk ring to set yours up, or download the YOUR DOORSTEP form from our website resources page OCTOBER - no more waiting -

Handlist 8: Parishes Indexed on the IGI and on Boyd's Marriage Index

Durham County Record Office County Hall Durham DH1 5UL Telephone: 03000 267619 Email: [email protected] Website: www.durhamrecordoffice.org.uk Handlist 8 – Parishes Indexed on the International Genealogical Index (IGI) and on Boyd’s Marriage Index Issue no. 14 July 2020 This list gives date ranges for those County Durham parish records that are included in the two major national indexes. Includes registers of baptisms, of marriages, of banns of marriage and, occasionally, of burials. County Durham parishes were not included in the Phillimore marriage index or Pallot’s marriage index. IGI Registers included in the 1992 microfiche of the International Genealogical Index, plus those added to the on-line version at FamilySearch.org by 2013. IGI includes surviving baptism and marriage records up to 1812 for all County Durham parishes and chapelries except: Bishopton, Croxdale, Elwick Hall, Hart, Hartlepool, Heighington, Kelloe, Lamesley, Penshaw, Sadberge, Satley, St John’s Chapel, Stockton, Stranton and Whitworth. Boyd Registers covered by Boyd’s Marriage Index of 1812, available here on Microfiche or on-line at FindMyPast.co.uk. AUCKLAND, ST. ANDREW BEAMISH – see Stanley BOLDON bap 1558-1653 IGI bap 1572-1812 IGI BEARPARK bap 1720-1897 IGI marr 1573-1812 IGI bap 1879-1901 IGI marr 1558-1877 IGI marr 1573-1812 Boyd marr 1879-1900 IGI marr 1558-1653 Boyd bann 1751-1812 Boyd BELMONT AUCKLAND, ST. HELEN BOWES bap 1858-1894 IGI bap 1653-1774 IGI bap 1615-1847 IGI marr 1858-1901 IGI bap 1798-1855 IGI marr 1615-1842 IGI bap 1864-1887 IGI