Chapter 13 Apollo and Icarus Daedalus Warned His Son Not to Fly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scottish Highlands Hillwalking

SHHG-3 back cover-Q8__- 15/12/16 9:08 AM Page 1 TRAILBLAZER Scottish Highlands Hillwalking 60 DAY-WALKS – INCLUDES 90 DETAILED TRAIL MAPS – INCLUDES 90 DETAILED 60 DAY-WALKS 3 ScottishScottish HighlandsHighlands EDN ‘...the Trailblazer series stands head, shoulders, waist and ankles above the rest. They are particularly strong on mapping...’ HillwalkingHillwalking THE SUNDAY TIMES Scotland’s Highlands and Islands contain some of the GUIDEGUIDE finest mountain scenery in Europe and by far the best way to experience it is on foot 60 day-walks – includes 90 detailed trail maps o John PLANNING – PLACES TO STAY – PLACES TO EAT 60 day-walks – for all abilities. Graded Stornoway Durness O’Groats for difficulty, terrain and strenuousness. Selected from every corner of the region Kinlochewe JIMJIM MANTHORPEMANTHORPE and ranging from well-known peaks such Portree Inverness Grimsay as Ben Nevis and Cairn Gorm to lesser- Aberdeen Fort known hills such as Suilven and Clisham. William Braemar PitlochryPitlochry o 2-day and 3-day treks – some of the Glencoe Bridge Dundee walks have been linked to form multi-day 0 40km of Orchy 0 25 miles treks such as the Great Traverse. GlasgowGla sgow EDINBURGH o 90 walking maps with unique map- Ayr ping features – walking times, directions, tricky junctions, places to stay, places to 60 day-walks eat, points of interest. These are not gen- for all abilities. eral-purpose maps but fully edited maps Graded for difficulty, drawn by walkers for walkers. terrain and o Detailed public transport information strenuousness o 62 gateway towns and villages 90 walking maps Much more than just a walking guide, this book includes guides to 62 gateway towns 62 guides and villages: what to see, where to eat, to gateway towns where to stay; pubs, hotels, B&Bs, camp- sites, bunkhouses, bothies, hostels. -

Glen Strathfarrar 1757

Title: Plan of the lands in Glen StrathFarrar. This title is taken from Adams (1979); no title on photostat. National Archive of Scotland Ref: nil, but photocopy of Mather photostats deposited in Highland Council Archives, Inverness. Tel. 01463 220 330 ref: HCA/D670. View by appointment. Location of Original: thought to be Lovat Estate Office, Beauly, Inverness-shire. Adams described this plan, as well as six others of Lovat lands, as ‘wanting’, in his 1979 publication, but apparently no attempt has since been made to trace them. Surveyor, Date and Purpose: Peter May, 1757 (as per Adams 1979); compiled as a requirement of Annexation to the Crown for the Commissioner to the Forfeited Estates, following the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745. Associated References: Mather, Alexander S., 1970, ‘Pre-1745 Land Use and Conservation in a Highland Glen: An Example from Glen Strathfarrar, North Inverness-shire’, Scottish Geographical Magazine 86 (3), 159-69. Adams, I. H. (ed.), 1979, Papers on Peter May Land Surveyor 1749-1793, Scottish History Society, 4th series, vol. 15. Description: photostats of this map were taken c.1970 from the Lovat Estate copy by A. Mather, now (’04) Head of Dept., Geography Dept., Aberdeen University, for his article in Scottish Geographical Magazine 86 (3) (1970), on land use. Working copy is a photocopy of these, although Mather’s original photostats were needed to check certain letters (not indicated here). Thirteen overlapping A3 photocopies make up this map. Professor Mather’s numbering scheme has been adopted - i.e. from west to east they are 1a/1b, 2a/2b etc, with ‘a’ the upper part of the map, and ‘b’ the lower part. -

View Away from the Teeming Masses at Morvich, and Across to Rhum the Venue for Some of Us in 1971

FORFAR AND DISTRICT HILL -WALKING CLUB NEWSLETTER No. 3 JUNE 1993 A FEW WORDS FROM THE PRESIDENT . Summer is here again. All hillwalkers like this time of year when the daylight is long, the hills are relatively dry and the air is warm. At the May weekend meet at Dundonnell, I saw my first swallow and wheatear of the year and heard my first cuckoo of the summer. Yet despite these signs, we were treated to biting cold winds and snow showers. Weekend meets are certainly popular these days. More so, since we have turned slightly soft and started using bunkhouses or hostels. On the other hand, the attendances at day meets continue to be disappointing. OK - we haven't been blessed with our fair share of good weather but where are you all? As you can see later in your new 93/94 meet calendar, due to the interest in weekend meets, the committee added a couple of weekends bring the total to 5. We are going to the Borders in September - tough luck for all you Munro-baggers but excellent hillwalking to be had. Our extra weekends are in November at Whitehaugh and in March at Roybridge. I have been assured by the hut custodian that the weekend will NOT be a work party but a truly social occasion! So bring your dancing shoes! Our March weekend is reinstating our "traditional" winter weekend which was dropped in favour of the May weekend a couple of years ago. But now we have both! Next May we return to Dundonnel to let some of us try the rocks on An Cheallaich again. -

The Highland Clans of Scotland

:00 CD CO THE HIGHLAND CLANS OF SCOTLAND ARMORIAL BEARINGS OF THE CHIEFS The Highland CLANS of Scotland: Their History and "Traditions. By George yre-Todd With an Introduction by A. M. MACKINTOSH WITH ONE HUNDRED AND TWENTY-TWO ILLUSTRATIONS, INCLUDING REPRODUCTIONS Of WIAN'S CELEBRATED PAINTINGS OF THE COSTUMES OF THE CLANS VOLUME TWO A D. APPLETON AND COMPANY NEW YORK MCMXXIII Oft o PKINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN CONTENTS PAGE THE MACDONALDS OF KEPPOCH 26l THE MACDONALDS OF GLENGARRY 268 CLAN MACDOUGAL 278 CLAN MACDUFP . 284 CLAN MACGILLIVRAY . 290 CLAN MACINNES . 297 CLAN MACINTYRB . 299 CLAN MACIVER . 302 CLAN MACKAY . t 306 CLAN MACKENZIE . 314 CLAN MACKINNON 328 CLAN MACKINTOSH 334 CLAN MACLACHLAN 347 CLAN MACLAURIN 353 CLAN MACLEAN . 359 CLAN MACLENNAN 365 CLAN MACLEOD . 368 CLAN MACMILLAN 378 CLAN MACNAB . * 382 CLAN MACNAUGHTON . 389 CLAN MACNICOL 394 CLAN MACNIEL . 398 CLAN MACPHEE OR DUFFIE 403 CLAN MACPHERSON 406 CLAN MACQUARIE 415 CLAN MACRAE 420 vi CONTENTS PAGE CLAN MATHESON ....... 427 CLAN MENZIES ........ 432 CLAN MUNRO . 438 CLAN MURRAY ........ 445 CLAN OGILVY ........ 454 CLAN ROSE . 460 CLAN ROSS ........ 467 CLAN SHAW . -473 CLAN SINCLAIR ........ 479 CLAN SKENE ........ 488 CLAN STEWART ........ 492 CLAN SUTHERLAND ....... 499 CLAN URQUHART . .508 INDEX ......... 513 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Armorial Bearings .... Frontispiece MacDonald of Keppoch . Facing page viii Cairn on Culloden Moor 264 MacDonell of Glengarry 268 The Well of the Heads 272 Invergarry Castle .... 274 MacDougall ..... 278 Duustaffnage Castle . 280 The Mouth of Loch Etive . 282 MacDuff ..... 284 MacGillivray ..... 290 Well of the Dead, Culloden Moor . 294 Maclnnes ..... 296 Maclntyre . 298 Old Clansmen's Houses 300 Maclver .... -

Calendar of Events 2021

Calendar of Events 2021 April 30 Apr Aonach Eagach Guided day rock-scrambling along the Aonach Eagach Ridge in Central Highlands, 2 Munros Summits : Meall Dearg (Aonach Eagach), Sgorr nam Fiannaidh (Aonach Eagach) http://www.stevenfallon.co.uk/guide-aonach-eagach.html May 1-2 May Kintail's Brothers and Sisters Hillwalking days on high crests in the Western Highlands, 7 Munros Summits : Ciste Dhubh, Aonach Meadhoin, Sgurr a' Bhealaich Dheirg, Saileag, Sgurr na Ciste Duibhe, Sgurr na Carnach, Sgurr Fhuaran http://www.stevenfallon.co.uk/guide-kintail.html 3-4 May Kintail Bookends Hill-walking day in the Western Highlands, 5 Munros Summits : Carn Ghluasaid, Sgurr nan Conbhairean, Sail Chaorainn, A' Ghlas-bheinn, Beinn Fhada http://www.stevenfallon.co.uk/guide-cluanie.html 4-7 May Skye Munros Hill-walking and rock-scrambling to summit the 11 Munros on the Cuillin Ridge of Skye. Includes some moderate climbing on the Inaccessible Pinnacle and Sgurr nan Gillean Summits : Sgurr nan Eag, Sgurr Dubh Mor, Sgurr Alasdair, Sgurr Mhic Choinnich, Sgurr Dearg - the Inaccessible Pinnacle, Sgurr na Banachdich, Sgurr a' Ghreadaidh, Sgurr a' Mhadaidh, Sgurr nan Gillean, Am Basteir, Bruach na Frithe http://www.stevenfallon.co.uk/guide-skye-munros.html 7 May An Teallach Day rock-scrambling the An Teallach main ridge in the Northern Highlands, 2 Munros Summits : An Teallach - Sgurr Fiona, An Teallach - Bidein a' Ghlas Thuill http://www.stevenfallon.co.uk/guide-anteallach.html 8-10 May Inverlael Munros Extended hill-walking weekend in the Northern Highlands, 6 Munro Summits : Eididh nan Clach Geala, Meall nan Ceapraichean, Cona' Mheall, Beinn Dearg, Seana Bhraigh, Am Faochagach http://www.stevenfallon.co.uk/guide-inverlael.html 10 May Aonach Eagach Guided day rock-scrambling along the Aonach Eagach Ridge in Central Highlands, 2 Munros Summits : Meall Dearg (Aonach Eagach), Sgorr nam Fiannaidh (Aonach Eagach) http://www.stevenfallon.co.uk/guide-aonach-eagach.html 11-14 May Skye Munros Hill-walking and rock-scrambling to summit the 11 Munros on the Cuillin Ridge of Skye. -

Moray Mountaineering Club Newsletter November 2012

Moray Mountaineering Club Newsletter November 2012 http://moraymc.wordpress.com The MMC Club Journals: Numbers 1 - 3 (1935, 1936 and 1950) In an effort to preserve original Moray Mountaineering Club Journals, and also to make a copy of journals available for members and non-members to read, I have digitised copies into PDF format. A copy of the 1935 Club Journal can now be downloaded by clicking on the following link: Download 1935 Journal. A copy of the 1936 Club Journal can now be downloaded by clicking on the following link: Download 1936 Journal. A copy of the 1950 Club Journal can now be downloaded by clicking on the following link: Download 1950 Journal. Please note that these journals are over 70 pages long (files are >8Mb each), so it may take a minute or two to download each of them. Thanks to Heavy Whalley for providing a loan of these journals. Andy Lawson 2013 Club Calendars now on sale 2013 Club calendars are now available, at the bargain price of only £6, from the following Committee members: Dan Moysey, Illona Morrice, Imke Henderson, Dave Whitelock, Jake Lee and Jenny Smith. All photos in the calendar have been taken by Club members. Special thanks to Glen Moray Distillery who have kindly sponsored the calendar again. Missing Photograph Album The Club has a number of albums of old photographs. Unfortunately one is currently missing. It was last seen at the 80th Anniversary dinner at the Mansion House Hotel. Would the person who borrowed it please return it to Daniel Moysey (or any other member of the committee). -

Summits on the Air Scotland

Summits on the Air Scotland (GM) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S4.1 Issue number 1.3 Date of issue 01-Sep-2009 Participation start date 01-July-2002 Authorised Tom Read M1EYP Date 01-Sep-2009 Association Manager Andy Sinclair MM0FMF Management Team G0HJQ, G3WGV, G3VQO, G0AZS, G8ADD, GM4ZFZ, M1EYP, GM4TOE Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. The source data used in the Marilyn lists herein is copyright of Alan Dawson and is used with his permission. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Summits on the Air – ARM for Scotland (GM) Page 2 of 47 Document S4.1 Summits on the Air – ARM for Scotland (GM) Table of contents 1 CHANGE CONTROL ................................................................................................................................. 4 2 ASSOCIATION REFERENCE DATA ...................................................................................................... 5 2.1 PROGRAMME DERIVATION ..................................................................................................................... 5 2.1.1 Mapping to Marilyn regions ............................................................................................................. 6 2.2 MANAGEMENT OF SOTA SCOTLAND ..................................................................................................... 7 2.3 GENERAL INFORMATION ....................................................................................................................... -

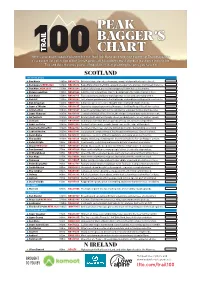

Peak Bagger's Chart

PEAK BAGGER’S CHART Here’s100 your downloadable planner for the Trail 100. Hand-picked by the experts at Trail magazine, it’s a bucket list collection of the 100 UK peaks all hillwalkers must climb at least once in their life. Tick and date the ones you’ve climbed, then start planning the ones you haven’t! SCOTLAND THE HIGHLANDS Ben Nevis 1345m NN166712 Britain’s highest peak; a stunning, complex labyrinth of routes for all. Ben Lawers NEW 2020 1214m NN635414 Bag a Munro from the 500m car park or as part of a glorious multi-peak traverse. Ben More NEW 2020 1174m NN433244 Sadistically steep, perfectly triangular; it dominates the skyline. Bidean nam Bian 1150m NN143542 A fortress of a mountain, closeted and grand – the highest in Glen Coe. Ben Alder 1148m NN496717 Fiercely remote and hard-won, but impressive and satisfying with it. Ben Lui 1130m NN265263 Tall, elegant gatekeeper to the Highlands, defined by amazing north-east corrie. Ben Cruachan 1126m NN069303 A massive presence, once thought to be Scotland’s highest peak. Sgurr a’ Mhaim 1099m NN164667 Quartzite-topped spur on the Mamores’ thrilling Ring of Steall horseshoe. Schiehallion 1083m NN714547 Scientifically important for its symmetry; a wonderful mountain besides. Sgurr Fhuaran 1067m NG978166 Central of Kintail’s Five Sisters. West ridge a stunningly sustained ascent. An Teallach 1060m NH063837 Brutally built and terrifyingly sheer; probably our scariest walker’s peak. Liathach 1055m NG929579 Dominates Torridon like an open bear trap. An awesome expedition. Sgurr na Ciche 1040m NM902966 Fantastically remote, rough, tough cone on the edge of Knoydart. -

Britain's Greatest Mountains

✁ BRITAIN’S GREATEST MOUNTAINS Here it is: your hundred-hill ticket to adventure. Download it , print it, laminate it... and most importantly, enjoy it! Mountain name Height Grid ref Trail says... Done/date W&S SCOTLAND Ben Nevis 1345m/4,411ft NN166712 Britain’s highest peak; a stunning, complex labyrinth of routes for all. Bidean nam Bian 1150m/3,773ft NN143542 A fortress of a mountain, closeted and grand – the highest in Glen Coe. Ben Alder 1148m/3,766ft NN496717 Fiercely remote and hard-won, but impressive and satisfying with it. Ben Lui 1130m/3,707ft NN265263 Tall, elegant gatekeeper to the Highlands, defined by amazing NE corrie. Ben Cruachan 1126m/3,694ft NN069303 A massive presence, once thought to be Scotland’s highest peak. Sgurr a’ Mhaim 1099m/3,606ft NN164667 Snaggly satellite of the Mamores’ thrilling Ring of Steall horseshoe. Schiehallion 1083m/3,553ft NN714547 Scientifically important for its symmetry; a wonderful mountain besides. Buachaille Etive Mór 1021m/3,351ft NN222542 Sentinel of Glen Coe; star of a million postcards. Demanding as a climb. The Saddle 1010m/3,314ft NG934129 Mighty and sharp, climbing this Glen Shiel hulk via Forcan Ridge is a must. Ben Lomond 974m/3,195ft NN367028 Most southerly Munro, many people’s first. Scenically stupendous. The Cobbler 884m/2,899ft NN259058 Collapsed, tortured jumble of a peak with a thrilling summit block. Merrick 843m/2,766ft NX427856 The highest point in a fascinating zone of incredibly rough uplands. CAIRNGORMS Ben Macdui 1309m/4,295ft NN988989 Brooding and sprawling, Britain’s deputy is a wilderness of a mountain. -

MUNROVERGROUND TUBULAR FELLS Copyright © 2012 P.M.Burgess

Lochboisdale DUNVEGAN LOCH Tarbet & Lochmaddy Stornoway (Lewis) Munro’s Tabular Hills NORTH All 283 Hills Over 3000’ Meall Key to table: Height in feet (metres), name of Munro, OS Landranger Map number and eight Figure Grid Reference Tuath 3070 (936) A' Bhuidheanach Bheag 42 NN66087759 3700 (1128) Creag Meagaidh 34 NN41878753 LOCH 6 hours 2 hours 3 hours Sandwood 3270 (997) A' Chailleach (Fannaichs) 19/20 NH13607141 3435 (1047) Creag Mhor (Glen Lochay) 50 NN39123609 SNIZORT Kilmaluag T H E M I N C H NW WATERNISH Bay 3051 (930) A' Chailleach (Monadh Liath) 35 NH68130417 3011 (918) Creag nan Damh 33 NG98361120 DUIRINISH 3674 (1120) A' Chralaig 33/34 NH09401481 3031 (924) Creag Pitridh 42 NN48758145 Flodigarry Cape Wrath Dunvegan L. SNIZORT BEAG HANDA 3011 (918) A' Ghlas-bheinn 25 NH00822307 3608 (1100) Creise 41 NN23845063 S E A OF T H E H E B R I D E S Uig L. LAXFORD 3064 (934) Am Basteir 32 NG46572530 3431 (1046) Cruach Ardrain 51 NN40922123 SW NE L. INCHARD Kinlochbervie 3385 (1032) Am Bodach 41 NN17656509 3789 (1155) Derry Cairngorm 36/43 NO01729804 Quiraing 3126 (953) Am Faochagach 20 NH30367938 3106 (947) Driesh 44 NO27137358 3172 (967) A' Mhaighdean 19 NH00787489 3238 (987) Druim Shionnach 33 NH07420850 SE Ferry 3198 (975) A' Mharconaich 42 NN60437629 3041 (927) Eididh nan Clach Geala 20 NH25788421 LOCH HARPORT LOCH ISLE OF The EDDRACHILLIS Scourie House 3264 (995) An Caisteal 50 NN37851933 3061 (933) Fionn Bheinn 20 NH14786213 LOCH TROTTERNISHOld Man 3028 (923) An Coileachan 20 NH 241680 BRACADALE of Storr BAY 3015 (919) Gairich 33 NN02489958 Laxford Durness 3221 (982) An Gearanach 41 NN18776698 3238 (987) Gaor Bheinn (Gulvain) 41 NN00288757 ENARD Bridge NORTH-WEST 3704 (1129) An Riabhachan 25 NH13373449 3323 (1013) Garbh Chioch Mhor 33 NM90989611 SUMMER KYLE OF DURNESS SKYE BAY Kylestrome 3300 (1006) An Sgarsoch 43 NN93348366 3441 (1049) Geal Charn (Loch Laggan) 42 NN50458117 ISLES SUTHERLAND Carbost 3507 (1069) An Socach (Loch Mullardoch) 25 NH10063326 3038 (926) Geal Charn (Monadh Liath) 35 NH56159879 Kylesku Foinaven SOUND L. -

The Structural Evolution of the Glenelg Inlier and Surrounding Morar Group

Glenelg_MS_SJG_NORA.docx Caledonian and Knoydartian overprinting of a Grenvillian inlier and the enclosing Morar Group rocks: structural evolution of the Precambrian Proto-Moine Nappe, Glenelg, NW Scotland M. Krabbendam 1, *, J. G. Ramsay 2, A. G. Leslie 1, P. W. G. Tanner 3, D. Dietrich 2& K. M. 1 Goodenough 1 British Geological Survey, Lyell Centre, Research Avenue South, Edinburgh EH14 4AP, UK 2 Cratoule, Issirac, France 3 School of Geographical and Earth Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G2 8QQ, UK * Corresponding author: email: [email protected] Keywords: Poly-orogenic; nappe; eclogite; refolding Abstract The Grenville and Caledonian orogens, fundamental to building Laurentia and Baltica, intersect in northern Scotland. The Precambrian Glenelg Inlier, within the Scottish Caledonides preserves a record of Grenvillian, Knoydartian and Caledonian orogenesis. Based on new mapping and re-interpretation of previous mapping, we present a structural model for the evolution of the Glenelg Inlier. The inlier can be divided into Western Glenelg gneiss comprising orthogneiss with no record of Grenville-age metamorphism, and Eastern Glenelg gneiss with ortho- and para-gneiss, affected by Grenvillian eclogite-facies metamorphism. The basement gneisses and their original cover of psammitic, Neoproterozoic Morar Group (Moine) rocks were deformed by three generations of major ductile folds (F1-F3). In medium-strain areas F2 and F3 folds are broadly coaxial and both face to the west; in higher strain areas F2 and F3 folds are oblique to each other. By restoring post-F1 folds and late faults, the Glenelg gneiss inliers are seen to form the core of a major recumbent SSE-facing F1 isoclinal fold nappe – the Proto-Moine Nappe. -

NEW ROUTES with a New Publication Date for the Journal, the Deadline for New Routes Each Year Is 1St August

NEW ROUTES With a new publication date for the Journal, the deadline for new routes each year is 1st August. Winter routes should still be sent at the end of winter. OUTER ISLES LEWIS, Butt of Lewis, (Rubha Robhanais): Immediately behind the lighthouse is a west facing pillar. Abseil to a narrow ledge from a carefully parked car on the cliff edge (check your handbrake!). Mondeo Man 20m HVS 5a. Charlie Henderson, Robert Durran. 9th July 2008. Climb a short steep crack above the left side of the ledge and then finish more easily rightwards. Trojan Wall (see SMCJ 2005): Access: abseil down the line of Trojan Horse from stakes 20m back (not in situ). It is possible from rocks but not advised as these are poor. The wall can be easily viewed from the cliff-top on the west side of the geo. The wall is split into four distinct sections, from left to right these are; Seaward Buttress, Three Corner Buttress, The Wall and Right End Wall. Right of this the rock is loose and broken. Routes are described from left to right starting at the large chimney in the corner that separates Seaward Buttress from Three Corner Buttress. Seaward Buttress The buttress at the left end of the wall contains Journey over the Sea (2004). Three Corner Buttress: The buttress that extends rightwards from the large chimney in the corner. Gniess Achilles (2004) climbs the left corner of the chimney. Apple of Discord 13m VS 4c. Ross Jones, Andrew Wardle. 6th September 2008. Climb the right corner of the chimney.