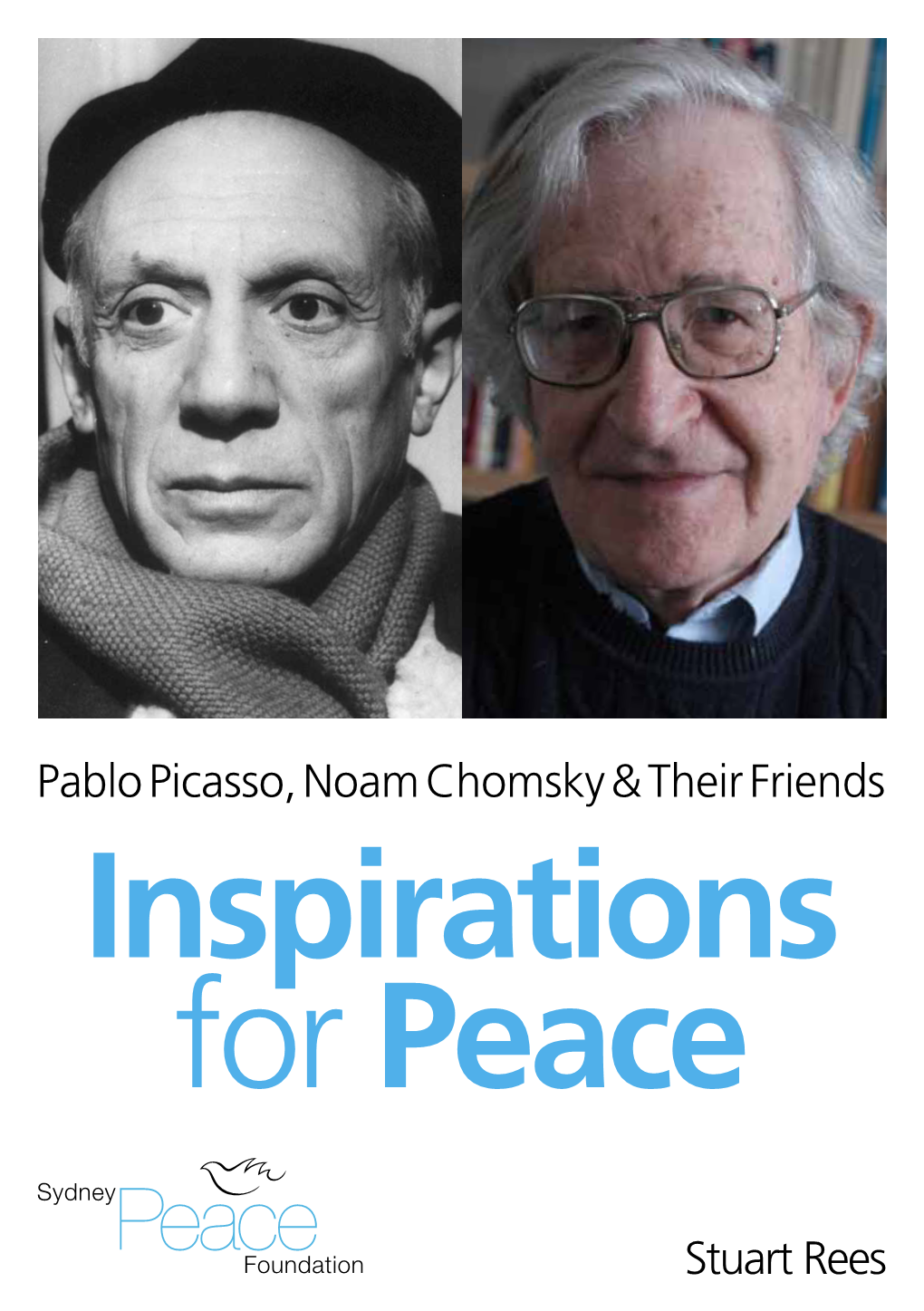

Pablo Picasso, Noam Chomsky & Their Friends

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Australian Media Reaction to Wikileaks

Globally Networked Public Spheres? The Australian Media Reaction to WikiLeaks Terry Flew & Bonnie Rui Liu – Creative Industries Faculty, Queensland University of Technology Abstract The global release of 250,000 US Embassy diplomatic cables to selected media sites worldwide through the WikiLeaks website, was arguably the major global media event of 2010. As well as the implications of the content of the cables for international politics and diplomacy, the actions of WikiLeaks and its controversial editor-in-chief, the Australian Julian Assange, bring together a range of arguments about how the media, news and journalism are being transformed in the 21st century. This paper will focus on the reactions of Australian online news media sites to the release of the diplomatic cables by WikiLeaks, including both the online sites of established news outlets such as The Australian, Sydney Morning Herald and The Age, the ABC’s The Drum site, and online-only sites such as Crikey, New Matilda and On Line Opinion. The study focuses on opinion and commentary rather than straight news reportage, and analysis is framed around three issues: WikiLeaks and international diplomacy; implications of WikiLeaks for journalism; and WikiLeaks and democracy, including debates about the organisation and the ethics of its own practice. It also whether a “WikiLeaks Effect” has wider implications for how journalism is conducted in the future, particularly the method of ‘redaction’ of large amounts of computational data. WikiLeaks and the public sphere theories The theory of the public sphere is commonly seen as one of the major contributions of media and communications theory to the social sciences. -

Australia's Silence on Tibet

AUSTRALIA’S SILENCE ON TIBET Australia Tibet Council 2017 How China is shaping our agenda AUSTRALIA’S SILENCE ON TIBET: How China is shaping our agenda Author: Kyinzom Dhongdue Editors: Kerri-Anne Chinn, Paul Bourke Australia Tibet Council acknowledges the input from the International Campaign for Tibet for this report. For further information on the issues raised in this report please email [email protected] ©Australia Tibet Council, September 2017 www.atc.org.au CONTENTS Executive summary 3 Chapter 1 - China’s influence on ustralianA politics and Tibet Australia’s response to Tibet 6 Chinese influence on Australian politics 8 Two Australian politicians with connections to China 11 Recommendations 12 Chapter 2 - China’s influence on Australian universities and Tibet A billion-dollar industry 13 Confucius Institutes 15 Case studies of two academics 18 Recommendations 19 Chapter 3 - Australia’s Tibetan community 20 Conclusion 22 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Under the leadership of the Dalai Lama, the Tibetans have earned widespread public support, with the Tibet cause continuing to test the conscience of world leaders. While China is far from winning over the international community on its policies in Tibet, in recent years it has been making rapid progress in numerous areas. Through a proactive foreign policy, utilising both economic leverage and soft power diplomacy, the Chinese government is making determined efforts to erode the support the Tibet movement has built up over many years. In Australia, China’s influence has infiltrated political and educational institutions, perhaps more than in any country in the western world. In fact, extensive reports in the Australian media over the past year have revealed an alarming level of Chinese influence in Australia. -

Social and Public Policy AUTUMN/WINTER 2021 SOCIAL and PUBLIC POLICY | 2

Social and Public Policy AUTUMN/WINTER 2021 SOCIAL AND PUBLIC POLICY | 2 IVER IVER BRAT N SI N SI E I U T U T L N L Y L Y G E O P O P C T R T R S E S E I I S S R R S S B B PUBLISHING WITH A PURPOSE F F S I S F I V R V R YEARSI V R S Welcome E Y E A E Y E A E Y E A This year Policy Press (PP) is celebrating 25 years since it was launched and Bristol University Press (BUP) is marking its fifth anniversary. PUBLISHING WITH A PURPOSE YEARS We publish pioneering scholarship In this catalogue, we are delighted and social commentary which to present our new titles for Autumn aims to influence research, and Winter 2021 and announce education, policy, practice and our new Open Access Global wider culture and thereby support Social Challenges Journal (pages social change. 4-5). Despite the challenges of the last 18 months, I hope that our Since the beginning, our mission work can help us to move closer has been to show the damage to a society that is caring and done to individuals and society compassionate to its people and by social problems and structural planet, challenging injustice and inequalities and how enlightened, discrimination in all its forms. evidence-based interventions can mediate this and positively change lives. Social challenges, from the local to the global, have of course become greater and ever more urgent: as 2020 has showed us, we can no ALISON SHAW, CEO longer talk about social justice without focusing on racial, gender and environmental justice. -

Ending War, Building Peace

ENDING WAR, BUILDING PEACE Edited by Lynda-ann Blanchard and Leah Chan Published 2009 by Sydney University Press SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS Fisher Library, University of Sydney www.sup.usyd.edu.au © Individual authors 2009 © Sydney University Press 2009 Reproduction and communication for other purposes Except as permitted under the Act, no part of this edition may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or communicated in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All requests for reproduction or communication should be made to Sydney University Press at the address below: Sydney University Press Fisher Library University of Sydney, NSW Australia 2006 Email: [email protected] National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Ending war, building peace / editors, Lynda-Ann Blanchard, Leah Chan. ISBN: 781920899431 (pbk.) Notes: Includes index. Bibliography. Subjects: Peace. Peace-building. Other Authors/Contributors: Blanchard, Lynda-Ann. Chan, Leah. Dewey Number: 327.172 Cover image: An Iraqi child carries tattered clothes across an empty lot in Sayda Zainab, ©Tamara Fenjan Cover design by Pria Adam Mützelburg Printed in Australia CONTENTS Foreword. Ending war, building peace ............................................v Lynda-ann Blanchard and Leah Chan Contributors ...................................................................................... ix Introduction. Thinking war, crafting peace: a future for Iraq and civil liberties in Australia .......................................................xiii -

Digital Edition

AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL REVIEW VOLUME 46 No. 7 JULY 2021 AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL & JEWISH AFFAIRS COUNCIL A GOVERNMENT LIKE NO OTHER The prospects and symbolism of Israel’s unique new governing coalition THE NETANYAHU PARADOX THE PRESIDENT’S THE PLACARD NOT CHILD’S PLAY MASSACRES STRATEGY How personal flaws brought down Israel’s Ugliness invades The alleged past human How not to think about the children’s book longest serving PM ............................. PAGE 20 rights abuses of newly- the Israeli-Palestinian industry ........ PAGE 40 selected Iranian Presi- conflict ..........PAGE 31 dent Raisi ........PAGE 25 NAME OF SECTION WITH COMPLIMENTS AND BEST WISHES FROM GANDEL GROUP CHADSTONE SHOPPING CENTRE 1341 DANDENONG ROAD CHADSTONE VIC 3148 TEL: (03) 8564 1222 FAX: (03) 8564 1333 2 AIR – July 2021 AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL VOLUME 46 No. 7 REVIEW JULY 2021 EDITOR’S NOTE NAME OF SECTION his AIR edition focuses on Israel’s unique and highly diverse new eight-party coalition ON THE COVER TGovernment. Members of Israel’s new Amotz Asa-El looks at the way this complicated, ideologically-diverse coalition gov- ministry led by Prime Min- ernment has been structured and what it can and cannot aspire to accomplish as a result. ister Naftali Bennett sit with In addition, we offer a profile of new Israeli PM Naftali Bennett from BICOM, plus President Reuven Rivlin in Je- profiles of other key players in the governing coalition penned by Zachary Milewicz and rusalem (Source: Israeli Prime Minister’s Office/ Flickr) other AIR staff. Finally, in the editorial, Colin Rubenstein points out how this diverse and democratic Government debunks the claims of Israel haters. -

Defending John Pilger's Journalism on Israel and Palestine

Jake Lynch (with the UK, and released in 2002, called Palestine additional research by is still the issue (PISTI). In the tradition of Catherine Dix and Stuart authored documentary film-making, it ends Rees) with a long in-vision commentary by Pilger himself, framed against the Jerusalem skyline. His concluding words were: Israelis will never have peace until they recognise that Palestinians have the same right to the same peace and the same inde- pendence that they enjoy. The occupation of Palestine should end now. Then, the solution is clear. Two countries, Israel and Palestine, neither dominating nor menacing the other. In an earlier sequence, Pilger made it clear Defending John that Palestinian independence meant a state in East Jerusalem, the West Bank and Gaza Pilger’s journalism on Strip, the territories occupied since 1967: Israel and Palestine [The establishment of the State of Israel] cost No sooner had the journalist and film-maker, the Palestinians 78 per cent of their country. John Pilger, been named the 2009 winner of Today, they are seeking only the remaining the Sydney Peace Prize, than a chorus of criti- 22 per cent of their homeland. For 35 years, cism broke out from Jewish groups objecting that homeland has been dominated by Israel. to his coverage of the Israel-Palestine conflict. This was conducted in public media and It was for films such as this – along with his included several contributions from Philip books and his regular column for the New Mendes, a social work academic from Monash Statesman magazine – that Pilger was named University, Melbourne, and a writer on the peace prize winner in succession to previ- Australian Jewish affairs. -

NONVIOLENCE NEWS FEBRUARY – MARCH - APRIL 2019 Issue 6.1 ISSN: 2202 - 9648

NONVIOLENCE NEWS FEBRUARY – MARCH - APRIL 2019 Issue 6.1 ISSN: 2202 - 9648 I have nothing new to teach the world. Truth and Nonviolence are as old as the hills. All I have done is to try experiments in both on as vast a scale as I could. - Mahatma Gandhi President’s Page Corruption is the biggest enemy of human rights. Gambhir Watts OAM, President, International Centre of Nonviolence Australia “Woman is the companion of man, gifted with equal mental capacity…If by strength is meant moral power, then woman is immeasurably man’s superior…If non-violence is the law of our being, the future is with women…” – Mahatma Gandhi "Achieving gender equality and empowering women and girls is the unfinished business of our time, and the greatest human rights challenge in our world." - UN Secretary-General, António Guterres In ancient civilized cultures women had highest regards and respect as such shared equally with men all facets of life. The modern concepts of ‘empowerment of women’; ‘gender equality’ etc were unheard of then. The role of women in orienting life and family were elucidated in Rig Vedic age. They enjoyed independence and self-reliance. Besides their domestic role, they had every access to education with tremendous potential to realize the highest truths. Many of them were seers who had an intellectual and spiritual depth. Women played an important role in maintaining the economic status of the family with the occupation of spinning, weaving, and needlework. Widow's remarriage was permitted in Rig Vedic society as evidenced in the funeral hymn in the Rig Veda. -

Legislative Assembly

5018 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Friday 14 November 2003 ______ Mr Speaker (The Hon. John Joseph Aquilina) took the chair at 10.00 a.m. Mr Speaker offered the Prayer. REGISTERED CLUBS AMENDMENT BILL Bill introduced and read a first time. Second Reading Mr GRANT McBRIDE (The Entrance—Minister for Gaming and Racing) [10.03 a.m.]: I move: That this bill be now read a second time. This highly anticipated bill makes amendments to the Registered Clubs Act that resulted from deliberations of the club industry task force. As honourable members may recall, on 22 August I announced the formation of the club industry task force. The task force comprises representatives of ClubsNSW, the Services Clubs Association, the New South Wales Bowling Association, the Club Managers Association of Australia, the Leagues Clubs Association of New South Wales, the Liquor, Hospitality and Miscellaneous Workers Union, the Department of Gaming and Racing and members of my personal staff. The aim of the task force was to develop a set of recommendations that would clearly identify and articulate what is expected of the club industry in New South Wales in the future. Particular emphasis was placed on the importance of transparency and accountability. The proposals that resulted from this process represent a significant step in addressing the concerns not only of many club members but also of the general community. This bill deals specifically with the provision of recommendations for legislative amendments to club governance, probity and various reporting requirements. The recommendations aim to raise and set a uniform high standard of transparency and accountability in reporting the activities of registered clubs. -

2014 REPORT on ANTISEMITISM in AUSTRALIA 1 October 2013 – 30 September 2014

of Australian Jewry ECAJ Public Fund 2014 REPORT on ANTISEMITISM in AUSTRALIA 1 October 2013 – 30 September 2014 This Report is produced to assist understanding of anti-Jewish violence, vandalism, harassment and prejudice in contemporary Australia Researched, written and compiled by JULIE NATHAN REPORT on ANTISEMITISM in AUSTRALIA 2014 1 October 2013 – 30 September 2014 This Report was written, researched and compiled by Julie Nathan, Research Officer, Executive Council of Australian Jewry (ECAJ) This document should not be reproduced or distributed, and the original work not quoted, without the express permission of the author. © Executive Council of Australian Jewry Inc. PO Box 1114, Edgecliff, NSW, 2027 Phone: 02 8353 8500 Email: [email protected] Published by ECAJ, and funded by ECAJ Public Fund, a public fund listed on the Register of Harm Prevention Charities under Subdivision 30-EA of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997. 9 November 2014 1 “The Holocaust did not begin in the gas chambers - it began with words.” - Professor Irwin Cotler, former Canadian Minister of Justice “Through the ages, anti-Semitism has been grounded in the foundational anti-Semitic paradigm. This has five elements: Jews are fundamentally different from non-Jews. Jews are noxious. Jews are willfully malevolent. Jews are powerful. Jews are therefore dangerous. Either implicit or explicitly stated is a sixth element: that Jews must be kept in check, at bay, or somehow eliminated. In every era, specific anti-Semitic elaborations and accusations build upon this foundational paradigm by adapting themselves to the local cultural, social and political conditions of the times.” - Daniel Jonah Goldhagen 2 CONTENTS 1. -

Sydney Peace Foundation Annual Report 2004

Annual Report 2004 The Sydney Peace Foundation is a partnership between business, media, public service, community and academic interests Contents Sydney Peace Foundation Profile 4 Sydney Peace Foundation Committee Members and Staff 4 Chairman’s Report 5 Director’s Report 7 Sydney Peace Prize 9 Sydney Peace Prize Events 2004 11 Foundation Events 2004 13 Scholarships and Research 14 Statement of Income & Expenditure 2004 15 Statement of Balances 2004 16 Partners in Peace 17 Acknowledgements 17 Arundhati Roy, winner of the 2004 Sydney Peace Prize (Photo – Pradip Krishen) Peace with justice is a way of thinking and acting which promotes non-violent solutions to everyday problems and provides the foundation of a civil society The Sydney Peace Foundation is a partnership between business, media, public service, community and academic interests. It is a not-for-profit organisation which is wholly funded by our Partners in Peace, and by the support of organisations and individuals with an interest in the promotion of peace with justice and the practice of non-violence. The Foundation ❖ selects and awards the Sydney Peace Prize ❖ recognises significant contributions to peace by young people through the Schools Peace Initiative ❖ develops corporate sector and community Committee Members understanding of the value of peace with justice Chair ❖ is a major sponsor of the Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies, funding research positions Mr Alan Cameron AM and projects ❖ awards scholarships and internships in peace, Director human rights and conflict resolution. Emeritus Professor Stuart Rees Why is peace with justice important? Executive Committee Peace with justice is a way of thinking and Dr Tim Fitzpatrick acting which promotes non-violent solutions to Mr David Hirsch every day problems and provides the foundation Mr Mark Kelly of a civil society. -

Prog Ogram / Ssaturday 16 / / / / / / /

16 PROGRAM / SATURDAY 16TH 08:00 Venue Doors Open 08:10 Auditorium Doors Open 08:30 WELCOME TO THE CONFERENCE Parade of Flags / Youth Exchange Students Conference Welcome / DG John Dodd National Anthem (One Verse) Local District Welcome / DG Phil Armstrong 08:50 Welcome: Rotary International President’s Representative / RIPPR Bhichai Rattakul SESSION 2: Youth Service Chair: Jade Catherall 09:10 Guest Speaker: Fighting Chance / Jordan O’Reilly 09:30 Guest Speakers: The 11Eleven Project / Dannielle Lauren / Alex McCann 09:50 Morning Tea SESSION 3: Vocational Service Chair: PP Peter Kirkwood PARALLEL SESSIONS 10:20 Keynote: Vocational Service 10:20 Youth / Kemuel Lam Paktsun Discussion Panel 10:45 Four Way Test Public Speaking Competition 11:15 Guest Speaker: SkillsOne 11:15 Social Media / Brian Wexham Discussion Panel 11:35 Vocational Excellence Awards / PP Margaret Sachs 12:00 Lunch & Club Showcase PROGRAM / SATURDAY 16TH 17 Keynote: Vocational Service Kemuel Lam Paktsun Australian Federal Police Kemuel Lam Paktsun is a Federal Agent with the Australian Federal Police (AFP). He has had a diverse career with the AFP working in the areas of international narcotic and criminal syndicates, people smuggling, counterfeit credit cards and counterfeit currency, taxation offences, major fraud, family law, computer crime, intelligence and most recently Counter Terrorism. Kemuel has worked on a number of multi-agency strike-forces investigating various Commonwealth, State and transnational offences. He has performed the role of investigator as well as intelligence officer. He has also served overseas with the United Nations in peacekeeping missions and participated in a study exchange with the United Kingdom Metropolitan Police. -

Professor Chomsky Will Be Available for Interviews Wednesday 2Nd November

MEDIA ALERT October, 2011 ‘In a time of violence and abuses of human rights, a brilliant, inspiring choice.’ Noam Chomsky in Australia to receive 2011 Sydney Peace Prize Distinguished American linguist, social scientist and human rights campaigner Professor Noam Chomsky is the 2011 recipient of the Sydney Peace Prize. Prof Chomsky will be in Sydney from Wednesday 2nd November to Friday 4th November to receive Australia’s only international prize for peace. In receiving the Sydney Peace Prize, Prof Chomsky joins significant previous recipients such as Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Arundhati Roy, Sir William Deane and former Secretary General of Amnesty International Irene Khan. Official public engagements to honour this award, hosted by the Sydney Peace Foundation and attended by Prof Chomsky, include: - Wednesday 2nd November, 7 pm Sydney Town Hall: City of Sydney Peace Prize Lecture by Prof Noam Chomsky. - Thursday 3rd November, 10:30am Sydney Opera House: Chaired by veteran Australian broadcaster Mary Kostakidis, Prof Chomsky answers audience questions on ‘Problems of Knowledge and Freedom’- linguistics, global politics, human rights, responses to climate change, the nature of democracy. - Thursday 3rd November, 7pm MacLaurin Hall, the University of Sydney: Gala Dinner when Patrick Dodson will award Noam Chomsky with the 2011 Sydney Peace Prize; a $50,000 prize and a hand-made glass trophy crafted by the Australian artist Brian Hirst. - Friday 4th November, 8:30am Cabramatta High School – “Voices Inspiring Peace”. A welcome by thousands of high school student, hundreds in national costumes from all over the world, in a music and dance festival to honour Noam Chomsky. The release of two dozen peace doves in that day’s finale is the last piece of Sydney hospitality for Noam Chomsky.