Israel in the Australian Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2014 – 2015

Annual Report 2014 – 2015 JewishCare’s Mission Support and strengthen the resilience and independence of community members in need BOARD ALLAN BOYD VIDOR LAWRENCE MYERS DR JEFFREY LIONEL President Honorary Treasurer ENGELMAN SHIRLI KIRSCHNER ALLAN VIDOR LAWRENCE MYERS Auditor and a Registered member of the Australian Tax Agent. Lawrence holds Jewish Holocaust Survivors Appointed as Director on Appointed as Director on several board position’s and Descendants, 29 June 2006. 26 June 2008. with private and not where his father is a past Born 29/03/1963 in Born on 17/04/1974 in for profit organisations. President. Sydney, Australia. Cape Town South Africa. Lawrence is also a SHIRLI KIRSCHNER Allan is the Managing Lawrence is the Managing non-executive director of Appointed as Director on Director of the Toga Group Director and founder of Breville Group Limited, 20 March 2013 of Companies, a property MBP Advisory Pty. Limited listed on the Australian development, construction, - a prominent high end Stock Exchange. Born 05/12/1964 in Tel investment and hospitality Sydney firm - which he DR JEFFREY Aviv Israel management group. established in 1998. Prior ENGELMAN Shirli has a Bachelor of He graduated from the to that, Lawrence spent Appointed as Director on Arts (Psychology) and Law University of NSW with 6 years in small and large 24 November 2005. (UNSW) and is a Nationally Bachelor of Commerce Chartered Accounting accredited mediator. and Laws degrees in 1985 firms. His client base Born 08/11/1962 in and was admitted as a spans a broad range of Sydney, Australia. She worked as a lawyer for Solicitor of the Supreme industries and activities six years before founding Jeffrey is a Court of NSW in 1986. -

The Palestinian-Israeli Experience Delivered on the 4Th of November, 2004 at the Joan B

Hanan Ashrawi, Ph.D. Concept, Context and Process in Peacemaking: The Palestinian-Israeli Experience Delivered on the 4th of November, 2004 at the joan b. kroc institute for peace & justice University of San Diego San Diego, California Hanan Ashrawi, Ph.D. Concept, Context and Process in Peacemaking: The Palestinian-Israeli Experience Edited by Emiko Noma CONTENTS Joan B. Kroc Institute for Peace & Justice 4 Joan B. Kroc Distinguished Lecture Series 6 Biography of Hanan Ashwari, Ph.D. 8 Interview with Dr. Hanan Ashwari by Dr. Joyce Neu 10 Introduction by Dr. Joyce Neu 22 Lecture - Concept, Context and Process in Peacemaking: 25 The Palestinian-Israeli Experience Questions and Answers 48 Related Resources 60 About the University of San Diego 64 Photo: Architectural Photography, Inc. Photography, Photo: Architectural 3 JOAN B. KROC INSTITUTE FOR PEACE & JUSTICE The mission of the Joan B. peacemaking, and allow time for reflection on their work. Kroc Institute for Peace & Justice (IPJ) is to foster peace, cultivate A Master’s Program in Peace & Justice Studies trains future leaders in justice and create a safer world. the field and will be expanded into the Joan B. Kroc School of Peace Studies, Through education, research and supported by a $50 million endowment from the estate of Mrs. Kroc. peacemaking activities, the IPJ offers programs that advance scholarship WorldLink, a year-round educational program for high school students and practice in conflict resolution from San Diego and Baja California connects youth to global affairs. and human rights. The Institute for Peace & Justice, located at the Country programs, such as the Nepal project, offer wide-ranging conflict University of San Diego, draws assessments, mediation and conflict resolution training workshops. -

Peace, Propaganda, and the Promised Land

1 MEDIA EDUCATION F O U N D A T I O N 60 Masonic St. Northampton, MA 01060 | TEL 800.897.0089 | [email protected] | www.mediaed.org Peace, Propaganda & the Promised Land U.S. Media & the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Transcript (News clips) Narrator: The Israeli-Palestinian conflict dominates American news coverage of International issues. Given the news coverage is America's main source of information on the conflict, it becomes important to examine the stories the news media are telling us, and to ask the question, Does the news reflect the reality on the ground? (News clips) Prof. Noam Chomsky: The West Bank and the Gaza strip are under a military occupation. It's the longest military occupation in modern history. It's entering its 35th year. It's a harsh and brutal military occupation. It's extremely violent. All the time. Life is being made unlivable by the population. Gila Svirsky: We have what is now quite an oppressive regime in the occupied territories. Israeli's are lording it over Palestinians, usurping their territory, demolishing their homes, exerting a very severe form of military rule in order to remain there. And on the other hand, Palestinians are lashing back trying to throw off the yoke of oppression from the Israelis. Alisa Solomon: I spent a day traveling around Gaza with a man named Jabra Washa, who's from the Palestinian Center for Human Rights and he described the situation as complete economic and social suffocation. There's no economy, the unemployment is over 60% now. Crops can't move. -

THE TRANSFORMATIVE ROLES of PALESTINIAN WOMEN in the ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN CONFLICT by MEGAN BA

AN ARMY OF ROSES FOR WAGING PEACE: THE TRANSFORMATIVE ROLES OF PALESTINIAN WOMEN IN THE ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN CONFLICT by MEGAN BAILEY A THESIS Presented to the Department of International Studies and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts June 2014 An Abstract of the Thesis of Megan Bailey for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of International Studies to be taken June 2014 Title: An Army of Roses for Waging Peace: The Transformative Roles of Palestinian Women in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Approved: __'_J ~-= - ....;::-~-'--J,,;...;_.....:~~:==:......._.,.,~-==~------ Professor FrederickS. Colby This thesis examines the different public roles Palestinian women have assumed during the contemporary history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The thesis uses the problematic juxtaposition between the high public visibility of female militants and relatively low visibility of female political figures as a basis for investigating individual Palestinian women and women's groups that have participated in the Palestinian public sphere from before the first Intifada to the present. The thesis addresses the current state of Palestine's political structure, how international sources of support for enhancing women's political participation might be implemented, and internal barriers Palestinian women face in becoming politically active and gaining leadership roles. It draws the conclusions that while Palestinian women do participate in the political sphere, greater cohesion between existing women's groups and internal support from society and the political system is needed before the number of women in leadership positions can be increased; and that inclusion of women is a necessary component ofbeing able to move forward in peace negotiations. -

Digital Edition

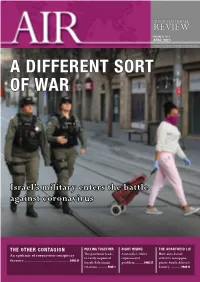

AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL REVIEW VOLUME 45 No. 4 APRIL 2020 AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL & JEWISH AFFAIRS COUNCIL A DIFFERENT SORT OF WAR Israel’s military enters the battle against coronavirus THE OTHER CONTAGION PULLING TOGETHER RIGHT RISING THE APARTHEID LIE An epidemic of coronavirus conspiracy The pandemic leads Australia’s white How anti-Israel to vastly improved supremacist activists misappro- theories ............................................... PAGE 21 Israeli-Palestinian problem ........PAGE 27 priate South Africa’s relations .......... PAGE 7 history ........... PAGE 31 WITH COMPLIMENTS NAME OF SECTION L1 26 BEATTY AVENUE ARMADALE VIC 3143 TEL: (03) 9661 8250 FAX: (03) 9661 8257 WITH COMPLIMENTS 2 AIR – April 2020 AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL VOLUME 45 No. 4 REVIEW APRIL 2020 EDITOR’S NOTE NAME OF SECTION his AIR edition focuses on the Israeli response to the extraordinary global coronavirus ON THE COVER Tpandemic – with a view to what other nations, such as Australia, can learn from the Israeli Border Police patrol Israeli experience. the streets of Jerusalem, 25 The cover story is a detailed look, by security journalist Alex Fishman, at how the IDF March 2020. Israeli authori- has been mobilised to play a part in Israel’s COVID-19 response – even while preparing ties have tightened citizens’ to meet external threats as well. In addition, Amotz Asa-El provides both a timeline of movement restrictions to Israeli measures to meet the coronavirus crisis, and a look at how Israel’s ongoing politi- prevent the spread of the coronavirus that causes the cal standoff has continued despite it. Plus, military reporter Anna Ahronheim looks at the COVID-19 disease. (Photo: Abir Sultan/AAP) cooperation the emergency has sparked between Israel and the Palestinians. -

A Conversation with Dr. Hanan Ashrawi

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by NSU Works A CONVERSATION WITH DR. HANAN ASHRAWI DoctorHanan Ashrawi* Introduction: Dr. Ashrawi was the official spokesperson at the Madrid Peace Process (also known as the Madrid Conference) for the Palestinian Delegation and will speak about those issues and whatever issues you would like to talk about.' Dr. Ashrawi: Anything you are interested in, I would be glad to address, related, of course, to what I have been doing. I am not going to address the latest space explorations, but I am quite willing to be diverse in talking about the Middle East Peace Process, how it started, the issues of Palestinian-Israeli realities, regional realities, questions related to human rights and democracy in the region, and developments in our part of the world. So, I do not know if you want me to begin with a brief presentation or if you would like to start with your questions and tell me what you are interested in, because every session I promise to be interactive, and then I end up lecturing, and this time I will do it too. I am going to have you ask questions and I will answer those questions. Student: Although Israel is negotiating with the Palestinian Authority 2 for * Hanan Ashrawi, who holds a Ph.D. in medieval literature from the University of Virginia, is the founder and Secretary General of the Palestinian Initiative for the Promotion of Global Dialogue and Democracy, an organization committed to human rights, democracy, and global dialogue in Jerusalem. -

Who Needs Norwegians?" Explaining the Oslo Back Channel: Norway’S Political Past in the Middle East

Evaluation Report 9/2000 Hilde Henriksen Waage "Norwegians? Who needs Norwegians?" Explaining the Oslo Back Channel: Norway’s Political Past in the Middle East A report prepared by PRIO International Peace Research Institute, Oslo Institutt for fredsforskning Responsibility for the contents and presentation of findings and recommendations rests with the author. The views and opinions expressed in the report do not necessarily correspond with the views of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Preface In September 1998, I was commissioned by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs to carry out a preliminary study looking into Norway’s role in the Middle East. According to the agreement with the Ministry, the study should focus on the years prior to 1993 and examine whether Norway’s political past in the Middle East – and, not least, the mediating and confidence-building efforts of Norwegians prior to the opening of the secret Oslo Back Channel – had had any influence on the process that followed. The study should also try to answer the question ‘Why Norway?’ – that is, what had made Norway, of all countries, suitable for such an extraordinary task? The work on the study started on 15 September 1998. The date of submission was stipulated as 15 April 2000. This was achieved. The following report is based on recently declassified and partly still classified documents (to which I was granted access) at the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the verbatim records of the Parliamentary Foreign Affairs Committee, records of government proceedings and the Norwegian Parliament, Labour Party Archives, documents from the US State Department and the Socialist International – to mention the most important. -

For 2021 Victoria`S Organisations List Click Here

1 The information contained in this directory has been provided by the organisations listed. The JCCV takes no responsibility for the accuracy of the information provided by the organisations, or lack thereof. # ACCESS INC Partners with young adults with disabilities to achieve goals CEO: Sharon Malecki T: 9272 5603 LJLA 304-306 Hawthorn Rd, Caulfield Sth 3162 PO Box 2401, Caulfield Junction 3161 [email protected] www.accessinc.org.au ADASS ISRAEL CONGREGATION 24 Glen Eira Ave, Ripponlea, 3183 T: 9523 1204, 9528 5632; Office: T: 9528 3079 [email protected] Adass Israel School 10-12 King St, & 86-90 Orrong Rd, Elsternwick 3185. Kindergarten-high school [email protected]; T: 9523 6422 Admin: Mr Moshe Nussbacher: [email protected] Adass Israel Chevra Kadisha 712 Princes Hwy, Springvale T: 9528 5424 Parlour: 16 Horne St, Elsternwick 3185 Caulfield-Adass Israel Mikvah 9 Furneaux Gve, East St Kilda 3183 T: 9528 1116 Ring for appointment. AIA – ASSOCIATION OF ISRAELIS IN AUSTRALIA www.ausraelim.com.au Pres: Eitan Drori 0414 235 567 Sec: Dr Ran Porat 0404 642 833 AISH AUSTRALIA Rabbi Andrew Saffer T: 1300 741 613 [email protected] www.aish.org.au 46 Balaclava Rd, St Kilda East Vic 3183 2 ALEPH MELBOURNE A support & advocacy group for people of diverse sexual orientation, gender identity and intersex status. [email protected] Unit 2/24 Winbirra Pde, Ashwood 3147 Michael Barnett T: 0417-595-541 www.aleph.org.au facebook.com/alephmelb ALIYAH CENTRE 306 Hawthorn Rd, Caulfield South 3162 T: 9272 5688 [email protected] ANTI-DEFAMATION -

The Australian Media Reaction to Wikileaks

Globally Networked Public Spheres? The Australian Media Reaction to WikiLeaks Terry Flew & Bonnie Rui Liu – Creative Industries Faculty, Queensland University of Technology Abstract The global release of 250,000 US Embassy diplomatic cables to selected media sites worldwide through the WikiLeaks website, was arguably the major global media event of 2010. As well as the implications of the content of the cables for international politics and diplomacy, the actions of WikiLeaks and its controversial editor-in-chief, the Australian Julian Assange, bring together a range of arguments about how the media, news and journalism are being transformed in the 21st century. This paper will focus on the reactions of Australian online news media sites to the release of the diplomatic cables by WikiLeaks, including both the online sites of established news outlets such as The Australian, Sydney Morning Herald and The Age, the ABC’s The Drum site, and online-only sites such as Crikey, New Matilda and On Line Opinion. The study focuses on opinion and commentary rather than straight news reportage, and analysis is framed around three issues: WikiLeaks and international diplomacy; implications of WikiLeaks for journalism; and WikiLeaks and democracy, including debates about the organisation and the ethics of its own practice. It also whether a “WikiLeaks Effect” has wider implications for how journalism is conducted in the future, particularly the method of ‘redaction’ of large amounts of computational data. WikiLeaks and the public sphere theories The theory of the public sphere is commonly seen as one of the major contributions of media and communications theory to the social sciences. -

Australia's Silence on Tibet

AUSTRALIA’S SILENCE ON TIBET Australia Tibet Council 2017 How China is shaping our agenda AUSTRALIA’S SILENCE ON TIBET: How China is shaping our agenda Author: Kyinzom Dhongdue Editors: Kerri-Anne Chinn, Paul Bourke Australia Tibet Council acknowledges the input from the International Campaign for Tibet for this report. For further information on the issues raised in this report please email [email protected] ©Australia Tibet Council, September 2017 www.atc.org.au CONTENTS Executive summary 3 Chapter 1 - China’s influence on ustralianA politics and Tibet Australia’s response to Tibet 6 Chinese influence on Australian politics 8 Two Australian politicians with connections to China 11 Recommendations 12 Chapter 2 - China’s influence on Australian universities and Tibet A billion-dollar industry 13 Confucius Institutes 15 Case studies of two academics 18 Recommendations 19 Chapter 3 - Australia’s Tibetan community 20 Conclusion 22 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Under the leadership of the Dalai Lama, the Tibetans have earned widespread public support, with the Tibet cause continuing to test the conscience of world leaders. While China is far from winning over the international community on its policies in Tibet, in recent years it has been making rapid progress in numerous areas. Through a proactive foreign policy, utilising both economic leverage and soft power diplomacy, the Chinese government is making determined efforts to erode the support the Tibet movement has built up over many years. In Australia, China’s influence has infiltrated political and educational institutions, perhaps more than in any country in the western world. In fact, extensive reports in the Australian media over the past year have revealed an alarming level of Chinese influence in Australia. -

Submission to the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence And

Australia/Israel & Jewish Affairs Council Submission to the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security on its Review of the re-listing of al-Shabaab, Hamas’ Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades (Hamas Brigades), the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), Lashkar-e-Tayyiba (LeT) and Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) as terrorist organisations under the Criminal Code. Introduction This document forms the submission by the Australia/Israel & Jewish Affairs Council (AIJAC) to the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security (PJCIS) on its review into the relisting of al-Shabaab, Hamas’ Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades (Hamas Brigades), the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), Lashkar-e-Tayyiba (LeT) and Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) as terrorist organisations under the Criminal Code 1995. This submission will focus on the relisting of Hamas’ Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades, though AIJAC also strongly supports the relisting of Palestinian Islamic Jihad: It recommends that the PJCIS not disallow the listing of the Hamas Brigades. It also recommends that the PJCIS advise the Minister for Home Affairs to extend the listing of Hamas’ Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades to Hamas in its entirety. There are three reasons why AIJAC makes these recommendations: 1. There is compelling and publicly available evidence to suggest all of Hamas, not just the Hamas Brigades, is engaged in activity that meets ASIO’s criteria for selecting an organisation to be listed under the Criminal Code 1995. 2. Last year, Yahya Sinwar, a long-time leader of the Hamas Brigades, was nominated Hamas leader in Gaza. This nomination provides recent and compelling evidence that there is no separation between Hamas and the Hamas Brigades. -

Democracy V. the Beast

15 Democracy v. the Beast Her appeal was simply that she represented something authentic in a culture of artefact. She was transparent in an era during which the political class have become expert at concealment. She was a still point in a culture of spin. She advanced our politics even if it was only to the extent of showing us what we might be up against if we chose to get involved as she did. Maybe others will learn from her mistakes Webdiarist Dr Tim Dunlop, an opponent of Pauline Hanson’s policies I do not believe that the real life of this nation is to be found either in the great luxury hotels and the petty gossip of so-called fashionable suburbs, or in the officialdom of organised masses. It is to be found in the homes of people who are nameless and unadvertised and who, whatever their individual religious conviction or dogma, see in their children their greatest contribution to the immortality of their race Robert Menzies, ‘The Forgotten People’, from The Forgotten People radio broadcasts, 1942 ast year a woman named Pauline approached me at a Lcafé in Marrickville and thanked me for a talk I’d given on refugees at the Marrickville town hall. She sat down for a chat and mentioned that she and her sister in Wollongong 298 Democracy v. the Beast 299 had long been at loggerheads over the boat people. Now they were in dispute over the recent jailing of Pauline Han- son – to her dismay, her sister believed that Pauline Hanson should not have gone to jail.