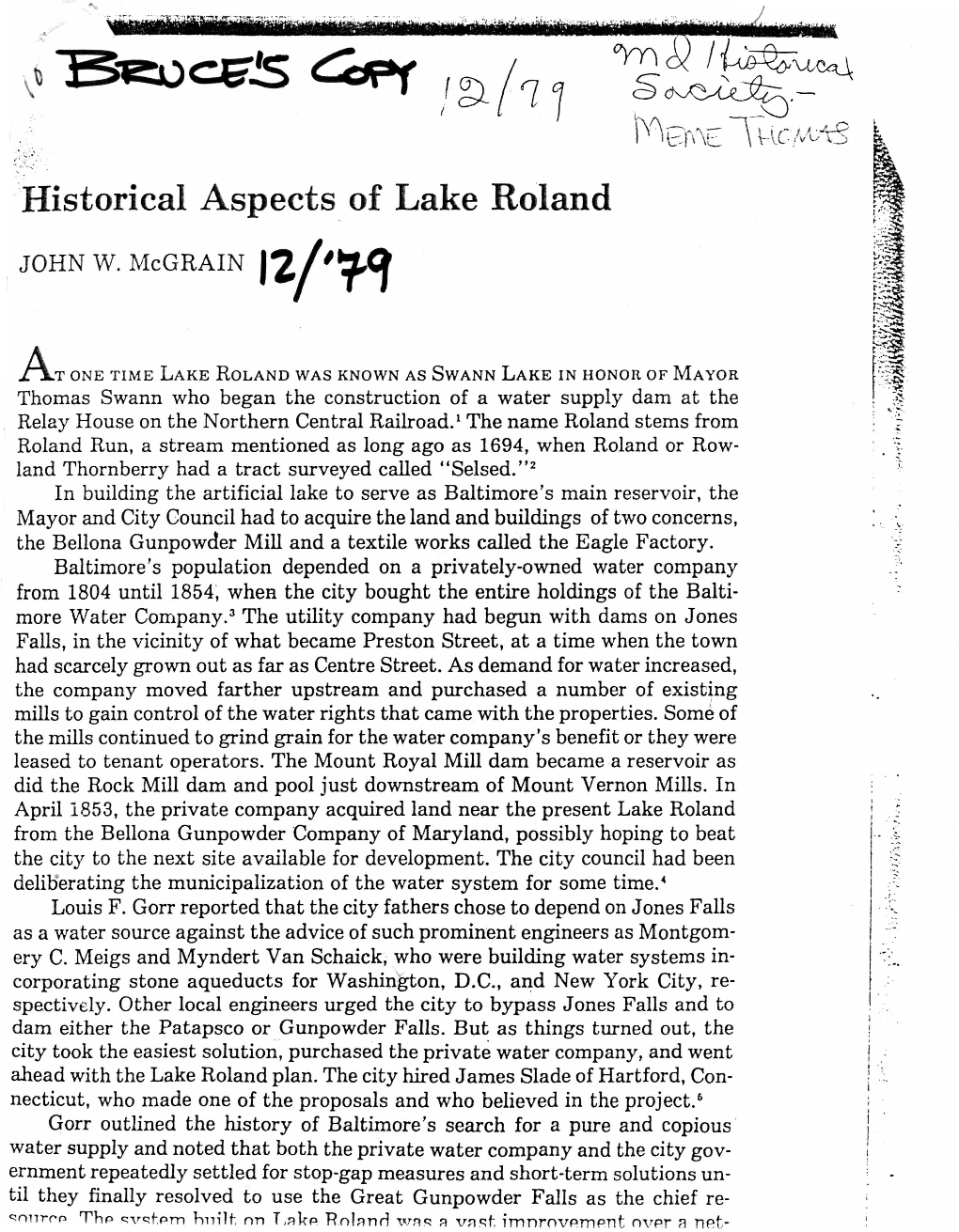

Historical Aspects of Lake Roland JOHN W. Mcgrain 12/07,,Cr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RPN Spring13

Spring 2013 Volume Forty-Nine ROLAND PARK NEWS Saying Goodbye…and Thank You…to Mille Fleurs By Kate Culotta medical school. Her residency at the University of We first became acquainted with Mille Fleurs about Maryland brought her to Maryland. Even before she 18 years ago, when fledgling florists Diane Pappas completed her medical training, she knew it wasn’t and Kathy Quinn took over the former But No going to be enough. Bunnies, a children’s clothing store in Wyndhurst When Pappas asked her husband for advice, he Station. Pappas and Quinn said, “Practice medicine first met during a two-year for a year, and if you’re certificate Florist Program not completely happy, you at Dundalk Community have my blessing to do College. Quinn wanted something else.” to leave her position with local interior designer, Rita One year later, Diane St. Clair, and Pappas was started taking classes at a practicing physician with Dundalk Community specialties in radiology and College and made a mammography. The pair ran new friend. Mille Fleurs together until It didn’t take long for two years ago, when Quinn’s Mille Fleurs, with Pappas other love, animal rescue, and Quinn at the helm, pulled at her heartstrings to make a name for itself, and pulled her away to start bringing sophisticated another adventure. floral designs and When I sat down with unparalleled service to Pappas a few weeks ago, I its clients. Even from the asked about her “it” talent. As start, the shop’s mantra I am in a creative field myself, has been “quality and I know you’ve either got it or service first.” Pappas has you don’t. -

Park Pavilions and Designated Picnic Areas for Rental

PARK PAVILIONS AND DESIGNATED PICNIC AREAS FOR RENTAL PARK ADDRESS Zip Pavilion Electricity Area Picnic Grill Capacity Gazebo Playground Basketball Court TennisCourt Field Ball AthleticField OutdoorPool WadingPool Skateboard BoatLaunce GolfCourse Center Rec Fee CARROLL PARK: AREA 1 MONROE ST. NR. WASHINGTON BLVD 21230 Y 100 Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y $85 CARROLL PARK: AREA 2 MONROE ST. NR. WASHINGTON BLVD 21230 Y 100 Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y $85 CLIFTON PARK DELEPORTE GROVE INDIAN HEAD DRIVE 21218 Y 75 Y Y Y Y $85 CLIFTON PARK BANDSHELL GROVE HARFORD RD & ST. LO DR 21218 Y 150 Y Y Y Y Y Y Y $85 DRUID HILL PARK - ATRIUM PAVILION RED ROAD & EAST DRIVE 21217 Y Y Y 100 Y Y $115 DRUID HILL PARK - CHINESE PAVILION SWAN DRIVE & EAST DRIVE 21217 Y Y Y 175 Y $170 DRUID HILL PARK - COLUMBUS PAVILION MANSION HOUSE DRIVE & EAST DRIVE 21217 Y Y Y 150 Y $140 DRUID HILL PARK - LIBERTY PAVILION LIBERTY HEIGHTS & BEECHWOOD 21217 Y Y Y 150 $140 DRUID HILL PARK - PARKIE EAST GROVE RED ROAD & EAST DRIVE 21217 Y 100 $85 DRUID HILL PARK - PARKIE LAKESIDE PAVILION RED ROAD & EAST DRIVE 21217 Y Y Y 150 Y Y $140 DRUID HILL PARK - PARKIE WEST GROVE RED ROAD & EAST DRIVE 21217 Y 100 $85 DRUID HILL PARK - SUNDIAL GROVE SWAN DRIVE 21217 Y 100 $85 DRUID HILL PARK - SUNDIAL PAVILION SWAN DRIVE 21217 Y Y Y 75 $115 DRUID HILL PARK - SUSQUEHANNOCK PAVILION EAST DRIVE 21217 Y Y Y 150 Y Y Y Y $140 DRUID HILL PARK - SWANN PAVILION RED ROAD & SHOP ROAD 21217 Y Y Y 100 Y Y $115 GWYNNS FALLS/LEAKIN PARK #1 4921 WINDSOR MILL RD 21217 Y Y 100 Y Y $85 GWYNNS FALLS/LEAKIN PARK #2 4921 WINDSOR MILL RD 21217 Y Y Y 100 Y Y $85 GWYNNS FALLS/LEAKIN PARK #3 4921 WINDSOR MILL RD 21217 Y Y Y 100 Y Y $85 GWYNNS FALLS/LEAKIN PARK #4 4921 WINDSOR MILL RD 21217 Y Y Y 100 Y Y $85 GWYNNS FALLS/WINANS MEADOW FRANKLINTOWN RD 21217 Y Y Y Y 200 $200 HANLON PARK 2400 LONGWOOD ST 21216 Y Y 100 Y $115 HERRING RUN PARK HARFORD RD & ARGONNE DR. -

John AJ Creswell of Maryland

Dickinson College Dickinson Scholar Faculty and Staff Publications By Year Faculty and Staff Publications 2015 Forgotten Abolitionist: John A. J. Creswell of Maryland John M. Osborne Dickinson College Christine Bombaro Dickinson College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.dickinson.edu/faculty_publications Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Osborne, John M., and Christine Bombaro. Forgotten Abolitionist: John A. J. Creswell of Maryland. Carlisle, PA: House Divided Project at Dickinson College, 2015. https://www.smashwords.com/books/ view/585258 This article is brought to you for free and open access by Dickinson Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Forgotten Abolitionist: John A.J. Creswell of Maryland John M. Osborne and Christine Bombaro Carlisle, PA House Divided Project at Dickinson College Copyright 2015 by John M. Osborne and Christine Bombaro Distributed by SmashWords ISBN: 978-0-9969321-0-3 License Notes: This book remains the copyrighted property of the authors. It may be copied and redistributed for personal use provided the book remains in its complete, original form. It may not be redistributed for commercial purposes. Cover design by Krista Ulmen, Dickinson College The cover illustration features detail from the cover of Harper's Weekly Magazine published on February 18, 1865, depicting final passage of Thirteenth Amendment on January 31, 1865, with (left to right), Congressmen Thaddeus Stevens, William D. Kelley, and John A.J. Creswell shaking hands in celebration. TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword by Matthew Pinsker Introduction Marylander Dickinson Student Politician Unionist Abolitionist Congressman Freedom’s Orator Senator Postmaster General Conclusion Afterword Notes Bibliography About the Authors FOREWORD It used to be considered a grave insult in American culture to call someone an abolitionist. -

Gunpowder River

Table of Contents 1. Polluted Runoff in Baltimore County 2. Map of Baltimore County – Percentage of Hard Surfaces 3. Baltimore County 2014 Polluted Runoff Projects 4. Fact Sheet – Baltimore County has a Problem 5. Sources of Pollution in Baltimore County – Back River 6. Sources of Pollution in Baltimore County – Gunpowder River 7. Sources of Pollution in Baltimore County – Middle River 8. Sources of Pollution in Baltimore County – Patapsco River 9. FAQs – Polluted Runoff and Fees POLLUTED RUNOFF IN BALTIMORE COUNTY Baltimore County contains the headwaters for many of the streams and tributaries feeding into the Patapsco River, one of the major rivers of the Chesapeake Bay. These tributaries include Bodkin Creek, Jones Falls, Gwynns Falls, Patapsco River Lower North Branch, Liberty Reservoir and South Branch Patapsco. Baltimore County is also home to the Gunpowder River, Middle River, and the Back River. Unfortunately, all of these streams and rivers are polluted by nitrogen, phosphorus and sediment and are considered “impaired” by the Maryland Department of the Environment, meaning the water quality is too low to support the water’s intended use. One major contributor to that pollution and impairment is polluted runoff. Polluted runoff contaminates our local rivers and streams and threatens local drinking water. Water running off of roofs, driveways, lawns and parking lots picks up trash, motor oil, grease, excess lawn fertilizers, pesticides, dog waste and other pollutants and washes them into the streams and rivers flowing through our communities. This pollution causes a multitude of problems, including toxic algae blooms, harmful bacteria, extensive dead zones, reduced dissolved oxygen, and unsightly trash clusters. -

All Hazards Plan for Baltimore City

All-Hazards Plan for Baltimore City: A Master Plan to Mitigate Natural Hazards Prepared for the City of Baltimore by the City of Baltimore Department of Planning Adopted by the Baltimore City Planning Commission April 20, 2006 v.3 Otis Rolley, III Mayor Martin Director O’Malley Table of Contents Chapter One: Introduction .........................................................................................................1 Plan Contents....................................................................................................................1 About the City of Baltimore ...............................................................................................3 Chapter Two: Natural Hazards in Baltimore City .....................................................................5 Flood Hazard Profile .........................................................................................................7 Hurricane Hazard Profile.................................................................................................11 Severe Thunderstorm Hazard Profile..............................................................................14 Winter Storm Hazard Profile ...........................................................................................17 Extreme Heat Hazard Profile ..........................................................................................19 Drought Hazard Profile....................................................................................................20 Earthquake and Land Movement -

This Special Bulletin Brings to You the Summary and Recommendations of the Whitman, Requardt and Associates Report on Lake Rolan

SPECIAL REPORT FROM Associates, Engineers, to do an engineering study on how THE LAKE ROLAND WATERSHED FOUNDATION, INC. best to remove silt now clogging the Lake, and collecting daily at a rapid rate. This study was authorized by Baltimore This special Bulletin brings to you the Summary and City and Baltimore County. Recommendations of the Whitman, Requardt and Associates (2) The offer of free dredging services for two months by report on Lake Roland, published in July, 1974. We are Ellicott Machine Corporation, and reduced labor-operating grateful to Mr. Douglas L. Tawney, Director, Baltimore City costs by C. J. Langenfelder & Company and the Operating Bureau of Recreation and Parks, for permission to do this. Engineers Union. We alsoprovide you with a map showing where the planned (3) Theformation of a tax-exempt, non-profit community basins will be and the location of the spoil areas. organization, under the auspices of the Ruxton-Riderwood We ask you to read this carefully so that you will know the Improvement Association, known as The Lake Roland facts when the community meeting is held Monday evening, Watershed Foundation, Inc. The Foundation will act as a September 30, in the Auditorium of the Church of the Good voice for the community, and will work to insure that any Shepherd, Boyce Avenue, Ruxton, at 8P.M. At this time, Mr. conservation program for Lake Roland is carefully and John B. Gillett of Whitman, Requardt and Associates, will sensitively executed. present the project and will try to answer any questions you (4) Expression of interest in the designation of Lake may have. -

Upstream, Downstream from Good Intentions to Cleaner Waters

Upstream, Downstream From Good Intentions to Cleaner Waters A Ground-Breaking Study of Public Attitudes Toward Stormwater in the Baltimore Area Sponsored by the Herring Run Watershed Association and the Jones Falls Watershed Association OpinionWorks / 2008 OpinionWorks Stormwater Action Coalition The Stormwater Action Coalition is a subgroup of the Watershed Advisory Group (WAG). WAG is an informal coalition of about 20 organizations from the Baltimore Metropolitan area who come together from time to time to interact with local government on water quality issues. WAG members represent all the region’s streams and waters and recently pressed the city and county to include stormwater as one of the five topics in the 2006 Baltimore City/Baltimore County Watershed Agreement. The Stormwater Action Coalition is focused on raising public awareness about the problems caused by contaminated urban runoff. Representa- tives of the following organizations have participated in Stormwater Action Coalition activities: Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay Baltimore Harbor Watershed Association Center for Watershed Protection Chesapeake Bay Foundation Clean Water Action Environment Maryland Friends of the Patapsco Valley Gunpowder Valley Conservancy Gwynns Falls Watershed Association Herring Run Watershed Association Jones Falls Watershed Association Parks & People Foundation Patapsco/Back River Tributary Team Prettyboy Watershed Alliance Watershed 263 We extend our appreciation to our local government colleagues: Baltimore City Department of Public Works Baltimore City Department of Planning Baltimore County Department of Environmental Protection and Resource Management Baltimore Metropolitan Council And to our funders: The Keith Campbell Foundation for the Environment The Rauch Foundation The Abell Foundation The Baltimore Community Foundation The Cooper Family Fund and the Cromwell Family Fund at the Baltimore Community Foundation More than half of the study participants strongly agree that they would do more, if they just knew what to do. -

MDE-Water Pollution

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION Chapters 01-10 Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT ........................................................................................... 1 Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION .................................................................................................................... 1 Chapters 01-10 ................................................................................................................................................ 1 Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT ........................................................................................... 2 Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION .................................................................................................................... 2 Chapter 01 General ......................................................................................................................................... 2 .01 Definitions................................................................................................................................................. 3 .02 Principles of Water Pollution Control.................................................................................................... -

Baltimore Police Department: Understanding Its Status As a State Agency

1 The Abell Report Published by the Abell Foundation March 2019 Volume 32, Number 2 The Baltimore Police Department: Understanding its status as a state agency by George A. Nilson Executive Summary remove the Commissioner remained with the Governor. In 1976, the General Assembly In recent years, the Baltimore Police Department transferred the appointment and removal has come under intense scrutiny following the powers to the Mayor of Baltimore. However, in-custody death of Freddie Gray in 2015 and the Maryland General Assembly left intact the the ensuing Department of Justice investigation, State Agency status of the Police Department. which resulted in a Federal Consent Decree. Many This means the General Assembly rather have started calling for turning control of the than the City Council is the legislative body Department back to the City from the State as a responsible for any legislative enactments way of increasing accountability. This report seeks governing the Baltimore Police Department. to understand the history of how the Department became a State Agency 158 years ago and the Throughout this 158-year history as a state implications of changing it now. agency, the funding of the operations of the Police Department has remained almost entirely By 1860, the Know-Nothing Party had taken the responsibility of the City of Baltimore. complete political control of Baltimore City and was abusing its power. The Maryland General While the Mayor and City Council are Assembly reached the conclusion that the Mayor constrained by the remaining Public Local and City Council had proven themselves incapable Laws establishing the Department’s continuing of maintaining order in Baltimore and accordingly status as a State Agency, the Mayor is able enacted Public Local Laws making the Baltimore to impact the conduct of the Commissioner Police Department a State Agency. -

The Chesapeake Bay Trust

The Chesapeake Bay Trust Working to promote public awareness and participation in the restoration and protection of the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries Annual Report 2003 From the Chairman Dear Friends of the Chesapeake Bay, With the help of many partners, volunteers, and donors, 2003 has been a terrific year for the Chesapeake Bay Trust. In 2003, the Trust was pleased to award more than $1.8 million in grants to nonprofit organizations, community groups, schools, and public agencies—an increase of nearly 50 percent from the previous year. This marks the highest level of annual grantmaking in the Trust’s 18-year history. Through this ambitious year of grantmaking, the Trust has supported hundreds of projects that benefit the Bay and involve the citizens of Maryland in the process. Trust grants helped plant stream- side forests to reduce water pollution and create important wildlife habitat. They supported innovative streambank stabilization projects—called “living shorelines”—that absorb polluted run-off and reestablish fish and crab habitat. And Trust grants gave thousands of Maryland students a greater appreciation for the Bay through hands-on experiences like skipjack trips and schoolyard habitat projects. The following pages detail these and other projects supported by the Trust at locations throughout the state. This report also summarizes other notable Trust activities in 2003, including a new scholarship, an urban watershed grant program, and a new design for the popular Treasure the Chesapeake license plate. In 2003, the Trust made significant strides in advancing its mission to promote public awareness and participation in the restoration and protection of the Chesapeake Bay and its rivers. -

Trip Schedule NOVEMBER 2013 – FEBRUARY 2014 the Club Is Dependent Upon the Voluntary Trail Policies and Etiquette Cooperation of Those Participating in Its Activities

Mountain Club of Maryland Trip Schedule NOVEMBER 2013 – FEBRUARY 2014 The Club is dependent upon the voluntary Trail Policies and Etiquette cooperation of those participating in its activities. Observance of the following guidelines will enhance the enjoyment The Mountain Club of Maryland (MCM) is a non-profit organization, of everyone: founded in 1934, whose primary concern is to provide its members and • Register before the deadline. Early registration for overnight or com- guests the opportunity to enjoy nature through hiking and other activi- plicated trips is especially helpful. Leaders may close registration early ties, particularly in the mountainous areas accessible to Baltimore. when necessary to limit the size of the trip. The leader may also refuse We publish a hike and activities schedule, with varieties in location registration to persons who may not be sufficiently strong to stay with and difficulty. We welcome guests to participate in most of our activi- the group. ties. We include some specialized hikes, such as family or nature hikes. • Trips are seldom canceled, even for inclement weather. Check with We help each other, but ultimately everyone is responsible for their the leader when conditions are questionable. If you must cancel, call individual safety and welfare on MCM trips. the leader before he or she leaves for the starting point. Members and We generally charge a guest fee of $2 for non-members. This fee is guests who cancel after trip arrangements have been made are billed waived for members of other Appalachian Trail maintaining clubs. Club for any food or other expenses incurred. members, through their dues, pay the expenses associated with publish- • Arrive early. -

Analysis of the Jones Falls Sewershed

GREEN TOWSON ALLIANCE WHITE PAPER ON SEWERS AUGUST 31, 2017 IS RAW SEWAGE CONTAMINATING OUR NEIGHBORHOOD STREAMS? ANALYISIS OF THE JONES FALLS SEWERSHED ADEQUATE PUBLIC SEWER TASK FORCE OF THE GREEN TOWSON ALLIANCE: Larry Fogelson, Retired MD State Planner, Rogers Forge Resident Tom McCord, Former CFO, and MD Industry CPA, Ruxton Resident Roger Gookin, Retired Sewer Contractor, Towsongate Resident JONES FALLS SEWER SYSTEM INVESTIGATION AND REPORT It is shocking that in the year 2017, human waste is discharged into open waters. The Green Towson Alliance (GTA) believes the public has a right to know that continuing problems with the Baltimore County sanitary sewer system are probably contributing to dangerous bacteria in Lake Roland and the streams and waterways that flow into it. This paper is the result of 15 months of inquiries and analysis of information provided by the County and direct observations by individuals with expertise in various professional disciplines related to this topic. GTA welcomes additional information that might alter our analysis and disprove our findings. To date, the generalized types of responses GTA has received to questions generated by our analysis do not constitute proof, or provide assurance, that all is well. 1. The Adequate Public Sewer Task Force of the Green Towson Alliance: The purpose of this task force is to protect water quality and public health by promoting the integrity and adequacy of the sanitary sewer systems that serve the Towson area. It seeks transparency by regulators and responsible officials to assure that the sewerage systems are properly planned, maintained, and operated in a manner that meets the requirements of governing laws and regulations.