Amgen Inc. V. Sanofi, No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recommendations for the Primary Analysis of Continuous Endpoints in Longitudinal Clinical Trials

02-DIJ42(4) 2348.qxd 6/9/08 1:46 PM Page 303 STATISTICS 303 Recommendations for the Primary Analysis of Continuous Endpoints in Longitudinal Clinical Trials Craig H. Mallinckrodt, PhD Research Advisor, Lilly This position paper summarizes relevant theo- simple methods in favor of joint analysis of Research Laboratories, Eli ry and current practice regarding the analysis data from all time points based on a multivari- Lilly and Company, of longitudinal clinical trials intended to sup- ate model (eg, of a mixed-effects type). One Indianapolis, Indiana port regulatory approval of medicinal prod- such newer method, a likelihood-based mixed- Peter W. Lane, MA, CStat ucts, and it reviews published research regard- effects model repeated measures (MMRM) ap- Director of Consultancy and Training, Research Statistics ing methods for handling missing data. It is proach, has received considerable attention in Unit, GlaxoSmithKline, one strand of the PhRMA initiative to improve the clinical trials literature. We discuss specif- Harlow, United Kingdom efficiency of late-stage clinical research and ic concerns raised by regulatory agencies with Dan Schnell, PhD gives recommendations from a cross-industry regard to MMRM and review published evi- Section Head, Pharmaceutical Statistics, team. We concentrate specifically on continu- dence comparing LOCF and MMRM in terms Procter & Gamble ous response measures analyzed using a linear of validity, bias, power, and type I error. Our Pharmaceuticals, model, when the goal is to estimate and test main conclusion is that the mixed model ap- Mason, Ohio treatment differences at a given time point. proach is more efficient and reliable as a Yahong Peng, PhD Traditionally, the primary analysis of such tri- method of primary analysis, and should be Senior Biometrician, Clinical Biostatistics, Merck als handled missing data by simple imputation preferred to the inherently biased and statisti- Research Lab, Upper using the last, or baseline, observation carried cally invalid simple imputation approaches. -

2012 Financial Markets Preview Living Creatively

REPRINT FROM JANUARY 2, 2012 BioCentury ™ THE BERNSTEIN REPORT ON BIOBUSINESS Article Reprint • Page 1 of 8 2012 Financial Markets Preview Living creatively By Stacy Lawrence “As the capital markets Viren Mehta of Mehta Partners. “Many Senior Writer companies don’t have any option but to For small, early stage biotech compa- continue to be difficult, raise at lower valuations.” nies, 2012 could be the year of living traditional investors are able He added: “Many companies are not creatively. able to defer any longer. The moment Although public biotechs raised more to extract terms that are comes for many companies when they funds last year than ever before, the vast have to swallow hard and accept painful majority of the money was debt financing more and more onerous.” dilution.” by established companies with marketed products. Thus while the overall numbers Todd Wyche, Brinson Patrick look good and are likely to continue to do Cash on hand so, precommercial companies will have to large and mid-cap companies (see “The Market volatility and macroeconomic get creative with their financings. 1% Effect,” page 2). risk had most buysiders sitting on the Many of these companies avoided rais- In 2011, public biotechs raised $43 sidelines through the back half of 2011. ing money in 2011 because they didn’t billion, easily eclipsing the record $33.1 Bankers are hopeful that this year will be like the valuations, but Wall Streeters say billion in 2000. But debt accounted for more stable, in which case investors might they are now running out of cash. As a 82% of the total dollars raised, compared be willing to support more deal flow dur- result, they will have to use the tricks at to only 19% in 2000 (see “Debt Domi- ing 1H12 (see “Fear Factor,” page 5). -

Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc. V. Actavis

United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit ______________________ ENDO PHARMACEUTICALS INC., MALLINCKRODT LLC, Plaintiffs-Appellees v. ACTAVIS LLC, FKA ACTAVIS INC., ACTAVIS SOUTH ATLANTIC LLC, TEVA PHARMACEUTICALS USA, INC., Defendants-Appellants ______________________ 2018-1054 ______________________ Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Delaware in No. 1:14-cv-01381-RGA, Judge Richard G. Andrews. ______________________ Decided: May 3, 2019 ______________________ MARTIN JAY BLACK, Dechert LLP, Philadelphia, PA, ar- gued for plaintiffs-appellees. Also represented by SHARON K. GAGLIARDI; BLAKE GREENE, Austin, TX; JONATHAN LOEB, Mountain View, CA; ROBERT RHOAD, Princeton, NJ. JEFFREY J. TONEY, Kasowitz, Benson, Torres & Fried- man LLP, Atlanta, GA, for plaintiff-appellee Mallinckrodt LLC. Also represented by RODNEY R. MILLER, PAUL GUNTER WILLIAMS. 2 ENDO PHARM. INC. v. ACTAVIS LLC JOHN C. O'QUINN, Kirkland & Ellis LLP, Washington, DC, argued for defendants-appellants. Also represented by WILLIAM H. BURGESS; CHARLES A. WEISS, ERIC H. YECIES, Holland & Knight, LLP, New York, NY. ______________________ Before WALLACH, CLEVENGER, and STOLL, Circuit Judges. Opinion for the court filed by Circuit Judge WALLACH. Dissenting opinion filed by Circuit Judge STOLL. WALLACH, Circuit Judge. Appellees Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc. (“Endo Pharma- ceuticals”) and Mallinckrodt LLC (“Mallinckrodt”) (collec- tively, “Endo”) sued Appellants Actavis LLC, Actavis South Atlantic LLC, and Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. (collec- tively, “Actavis”) in the U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware (“District Court”), alleging that two Abbrevi- ated New Drug Applications filed by Actavis infringed claims 1–6 (“the Asserted Claims”) of Mallinckrodt’s U.S. Patent No. 8,871,779 (“the ’779 patent”), which Endo Phar- maceuticals licenses. -

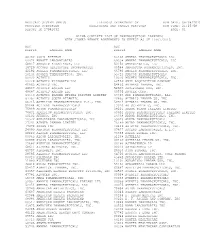

Medicaid System (Mmis) Illinois Department of Run Date: 08/08/2015 Provider Subsystem Healthcare and Family Services Run Time: 21:25:58 Report Id 2794D052 Page: 01

MEDICAID SYSTEM (MMIS) ILLINOIS DEPARTMENT OF RUN DATE: 08/08/2015 PROVIDER SUBSYSTEM HEALTHCARE AND FAMILY SERVICES RUN TIME: 21:25:58 REPORT ID 2794D052 PAGE: 01 ALPHA COMPLETE LIST OF PHARMACEUTICAL LABELERS WITH SIGNED REBATE AGREEMENTS IN EFFECT AS OF 10/01/2015 NDC NDC PREFIX LABELER NAME PREFIX LABELER NAME 68782 (OSI) EYETECH 65162 AMNEAL PHARMACEUTICALS LLC 00074 ABBOTT LABORATORIES 69238 AMNEAL PHARMACEUTICALS, LLC 68817 ABRAXIS BIOSCIENCE, LLC 53150 AMNEAL-AGILA, LLC 16729 ACCORD HEALTHCARE INCORPORATED 00548 AMPHASTAR PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 42192 ACELLA PHARMACEUTICALS, LLC 66780 AMYLIN PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 10144 ACORDA THERAPEUTICS, INC. 55724 ANACOR PHARMACEUTICALS 00472 ACTAVIS 10370 ANCHEN PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 00228 ACTAVIS ELIZABETH LLC 62559 ANIP ACQUISITION COMPANY 45963 ACTAVIS INC. 54436 ANTARES PHARMA, INC. 46987 ACTAVIS KADIAN LLC 52609 APO-PHARMA USA, INC. 49687 ACTAVIS KADIAN LLC 60505 APOTEX CORP. 14550 ACTAVIS PHARMA MFGING PRIVATE LIMITED 63323 APP PHARMACEUTICALS, LLC. 67767 ACTAVIS SOUTH ATLANTIC 42865 APTALIS PHARMA US, INC 66215 ACTELION PHARMACEUTICALS U.S., INC. 58914 APTALIS PHARMA US, INC. 52244 ACTIENT PHARMACEUTICALS 13310 AR SCIENTIFIC, INC. 75989 ACTON PHARMACEUTICALS 08221 ARBOR PHARM IRELAND LIMITED 76431 AEGERION PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 60631 ARBOR PHARMACEUTICALS IRELAND LIMITED 50102 AFAXYS, INC. 24338 ARBOR PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 10572 AFFORDABLE PHARMACEUTICALS, LLC 59923 AREVA PHARMACEUTICALS 27241 AJANTA PHARMA LIMITED 76189 ARIAD PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 17478 AKORN INC 24486 ARISTOS PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 24090 AKRIMAX PHARMACEUTICALS LLC 67877 ASCEND LABORATORIES, L.L.C. 68220 ALAVEN PHARMACEUTICAL, LLC 76388 ASPEN GLOBAL INC. 00065 ALCON LABORATORIES, INC. 51248 ASTELLAS 00998 ALCON LABORATORIES, INC. 00469 ASTELLAS PHARMA US, INC. 25682 ALEXION PHARMACEUTICALS 00186 ASTRAZENECA LP 68611 ALIMERA SCIENCES, INC. -

Amgen 2008 Annual Report and Financial Summary Pioneering Science Delivers Vital Medicines

Amgen 2008 Annual Report and Financial Summary Pioneering science delivers vital medicines About Amgen Products Amgen discovers, develops, manufactures Aranesp® (darbepoetin alfa) and delivers innovative human therapeutics. ® A biotechnology pioneer since 1980, Amgen Enbrel (etanercept) was one of the fi rst companies to realize ® the new science’s promise by bringing EPOGEN (Epoetin alfa) safe and effective medicines from the lab Neulasta® (pegfi lgrastim) to the manufacturing plant to patients. NEUPOGEN® (Filgrastim) Amgen therapeutics have changed the practice of medicine, helping millions of Nplate® (romiplostim) people around the world in the fi ght against ® cancer, kidney disease, rheumatoid Sensipar (cinacalcet) arthritis and other serious illnesses, and so Vectibix® (panitumumab) far, more than 15 million patients worldwide have been treated with Amgen products. With a broad and deep pipeline of potential new medicines, Amgen remains committed to advancing science to dramatically improve people’s lives. 0405 06 07 08 0405 06 07 08 0405 06 07 08 0405 06 07 08 Total revenues “Adjusted” earnings Cash fl ow from “Adjusted” research and ($ in millions) per share (EPS)* operations development (R&D) expenses* (Diluted) ($ in millions) ($ in millions) 2008 $15,003 2008 $4.55 2008 $5,988 2008 $2,910 2007 14,771 2007 4.29 2007 5,401 2007 3,064 2006 14,268 2006 3.90 2006 5,389 2006 3,191 2005 12,430 2005 3.20 2005 4,911 2005 2,302 2004 10,550 2004 2.40 2004 3,697 2004 1,996 * “ Adjusted” EPS and “adjusted” R&D expenses are non-GAAP fi nancial measures. See page 8 for reconciliations of these non-GAAP fi nancial measures to U.S. -

UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Form

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington D.C. 20549 Form 10-K (Mark One) ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF ☒ 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2008 OR TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT ☐ OF 1934 Commission file number 000-12477 Amgen Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 95-3540776 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) One Amgen Center Drive, 91320-1799 Thousand Oaks, California (Zip Code) (Address of principal executive offices) (805) 447-1000 (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: Common stock, $0.0001 par value; preferred share purchase rights (Title of class) Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if disclosure of delinquent filers pursuant to Item 405 of Regulation S-K is not contained herein, and will not be contained, to the best of registrant’s knowledge, in definitive proxy or information statements incorporated by reference in Part III of this Form 10-K or any amendment to this Form 10-K. -

Driving Awareness and Action Around the Country's

THANKS DRIVING TO AWARENESS ALL OUR DONORS AND ACTION AROUND THE COUNTRY’S OPIOID CRISIS $500,000 and over Leon D. Black Sonenshine Partners Human Services (Birmingham, MI) Google Bostock Family Foundation Sovereign Health of California Ibra Morales Conrad N. Hilton Foundation The Boucher Charitable Foundation Partnership for a Drug-Free Wash- National Association of Broadcast- Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation, Inc. ington (Lacey, WA) ers $250,000-$499,999 Timothy J. Brosnan Staten Island Partnership for Com- Gordon Ogden Consumer Healthcare Products Craig D. Brown munity Wellness (Staten Island, NY) Pascack Valley High School Association The Bruni Foundation Televisa, S.A. de C.V. George Patterson CVS Health Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton, LLP Truth Initiative PepsiCo, Inc. Jazz Pharmaceuticals Corning Incorporated Foundation Turn 2 Foundation Donald K. Peterson Major League Baseball The Council on Alcohol & Drug Turner Broadcasting Systems, Inc. Thomas Reuters Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals Abuse (Dallas, TX) Venable LLP Tamara Robinson Pharmaceutical Research & The Marvin H. Davidson Foundation Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Marc Rosenbaum Manufacturers of America Inc. The Xerox Foundation Mitchell S. Rosenthal, M.D. Purdue Pharma L.P. Deloitte Services LLP Rye City School District Discovery Communications $1,000-$4,999 Andrew Scott $100,000-$249,999 DrugFreeAZKids.org (Phoenix, AZ) All Filters, LLC Jeff Shiver James E. & Diane W. Burke Fox Broadcasting Company Bill Anderson Roberto Simon Foundation Joan Ganz Cooney AOL, Inc. Simulmedia, Inc. Millenium Health, LLC General Electric Company Auburn Pharmaceutical Yvette A. Smith Pfizer Inc. The Gottesman Fund The Ayco Company, LP Karen Spence Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz The Governor’s Prevention Partner- Bob Bailey Allan Spivack ship (Wethersfield, CT) Bernstein Investment Research & State of Maine Department of $25,000-$99,999 Hawaii Meth Project Management Health and Human Services Alkermes HBO C.R. -

Compliance Officers.Xlsx

Compliance Officers.xlsx Organization Representative Title Email Phone AbbVie Inc. Karen Hale Vice President, Chief Ethics & Compliance Officer [email protected] 847-932-7850 Amgen Inc. Cynthia Patton Senior Vice President, Chief Compliance Officer [email protected] 805-447-6217 Anacor Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Ryan T. Sullivan Senior Vice President and General Counsel [email protected] 650-543-7500 Astellas Pharma US, LLC Nahrin Marino Vice President, Head of Ethics & Compliance [email protected] 224-205-5618 Americas AstraZeneca LP Trudy Tan Vice President Compliance, North America [email protected] 302-885-5692 Bayer Corporation Lawrence Platkin Vice President and Compliance Officer [email protected] 973-305-5439 Biogen Soph Sophocles Chief Compliance Officer [email protected] 781-464-1943 Boehringer Ingelheim Joshua Marks Chief Ethics and Compliance Officer [email protected] Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company Adam Dubow Chief Compliance and Ethics Officer [email protected] 609-252-3034 Celgene Corporation Maria E. Pasquale EVP and Chief Compliance Officer [email protected] 908-673-9757 Cell Therapeutics, Inc. Steven E. Benner, M.D. Executive Vice President & Chief Medical Officer [email protected] 206-272-4652 Corcept Therapeutics Inc. G. Charles Robb Chief Financial Officer / Compliance Officer [email protected] 650-688-8783 Cumberland Pharmaceuticals James Herman Corporate Compliance Officer [email protected] 615-255-0068 Inc. Daiichi Sankyo, Inc. Matt Allegrucci Vice President, Chief Ethics & Compliance Officer [email protected] 908-992-6674 Eisai Inc. Vincent P. Andrews Vice President, General Counsel and Chief [email protected] 201-746-2938 Compliance Officer Senior Vice President ERM and Chief Compliance Melissa Stapleton Eli Lilly and Company Officer [email protected] 317-276-2923 Barnes EMD Serono, Inc. -

Patient Services, Inc. 2014 Annual Report Table of Contents

Patient Services, Inc. 2014 Annual Report Table of ConTenTs 2014 Board of Directors and Sponsors .......................................................................................... 3 Pharmaceutical, Provider Industries, Corporate, Government and Individual Sponsors ............ 3-5 Ways to Support PSI ..................................................................................................................... 6 2014 Executive Message ................................................................................................................ 7 Marketing and Development ........................................................................................................ 8 Government Relations .................................................................................................................. 9 Operations and Program Reimbursement ....................................................................................10 PSI Traditional Programs ....................................................................................................... 11-13 IT Department ............................................................................................................................14 ACCESS® Program ......................................................................................................................15 Message from our Board Treasurer ..............................................................................................16 Statement of Activities .................................................................................................................17 -

Rxoutlook® 4Th Quarter 2020

® RxOutlook 4th Quarter 2020 optum.com/optumrx a RxOutlook 4th Quarter 2020 While COVID-19 vaccines draw most attention, multiple “firsts” are expected from the pipeline in 1Q:2021 Great attention is being given to pipeline drugs that are being rapidly developed for the treatment or prevention of SARS- CoV-19 (COVID-19) infection, particularly two vaccines that are likely to receive emergency use authorization (EUA) from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the near future. Earlier this year, FDA issued a Guidance for Industry that indicated the FDA expected any vaccine for COVID-19 to have at least 50% efficacy in preventing COVID-19. In November, two manufacturers, Pfizer and Moderna, released top-line results from interim analyses of their investigational COVID-19 vaccines. Pfizer stated their vaccine, BNT162b2 had demonstrated > 90% efficacy. Several days later, Moderna stated their vaccine, mRNA-1273, had demonstrated 94% efficacy. Many unknowns still exist, such as the durability of response, vaccine performance in vulnerable sub-populations, safety, and tolerability in the short and long term. Considering the first U.S. case of COVID-19 was detected less than 12 months ago, the fact that two vaccines have far exceeded the FDA’s guidance and are poised to earn EUA clearance, is remarkable. If the final data indicates a positive risk vs. benefit profile and supports final FDA clearance, there may be lessons from this accelerated development timeline that could be applied to the larger drug development pipeline in the future. Meanwhile, drug development in other areas continues. In this edition of RxOutlook, we highlight 12 key pipeline drugs with potential to launch by the end of the first quarter of 2021. -

05/09/2016 Provider Subsystem Healthcare and Family Services Run Time: 04:25:50 Report Id 2794D052 Page: 01

MEDICAID SYSTEM (MMIS) ILLINOIS DEPARTMENT OF RUN DATE: 05/09/2016 PROVIDER SUBSYSTEM HEALTHCARE AND FAMILY SERVICES RUN TIME: 04:25:50 REPORT ID 2794D052 PAGE: 01 ALPHA COMPLETE LIST OF PHARMACEUTICAL LABELERS WITH SIGNED REBATE AGREEMENTS IN EFFECT AS OF 07/01/2016 NDC NDC PREFIX LABELER NAME PREFIX LABELER NAME 68782 (OSI) EYETECH 55513 AMGEN USA 00074 ABBOTT LABORATORIES 58406 AMGEN/IMMUNEX 68817 ABRAXIS BIOSCIENCE, LLC 53746 AMNEAL PHARMACEUTICALS 16729 ACCORD HEALTHCARE INCORPORATED 65162 AMNEAL PHARMACEUTICALS LLC 42192 ACELLA PHARMACEUTICALS, LLC 69238 AMNEAL PHARMACEUTICALS, LLC 10144 ACORDA THERAPEUTICS, INC. 53150 AMNEAL-AGILA, LLC 00472 ACTAVIS 00548 AMPHASTAR PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 00228 ACTAVIS ELIZABETH LLC 69918 AMRING PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 45963 ACTAVIS INC. 66780 AMYLIN PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 46987 ACTAVIS KADIAN LLC 55724 ANACOR PHARMACEUTICALS 49687 ACTAVIS KADIAN LLC 10370 ANCHEN PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 14550 ACTAVIS PHARMA MFGING PRIVATE LIMITED 43595 ANGELINI PHARMA, INC. 61874 ACTAVIS PHARMA, INC. 62559 ANIP ACQUISITION COMPANY 67767 ACTAVIS SOUTH ATLANTIC 54436 ANTARES PHARMA, INC. 66215 ACTELION PHARMACEUTICALS U.S., INC. 52609 APO-PHARMA USA, INC. 52244 ACTIENT PHARMACEUTICALS 60505 APOTEX CORP. 75989 ACTON PHARMACEUTICALS 63323 APP PHARMACEUTICALS, LLC. 69547 ADAPT PHARMA INC. 43485 APRECIA PHARMACEUTICALS COMPANY 76431 AEGERION PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 42865 APTALIS PHARMA US, INC 50102 AFAXYS, INC. 58914 APTALIS PHARMA US, INC. 10572 AFFORDABLE PHARMACEUTICALS, LLC 13310 AR SCIENTIFIC, INC. 27241 AJANTA PHARMA LIMITED 08221 ARBOR PHARM IRELAND LIMITED 17478 AKORN INC 60631 ARBOR PHARMACEUTICALS IRELAND LIMITED 24090 AKRIMAX PHARMACEUTICALS LLC 24338 ARBOR PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 68220 ALAVEN PHARMACEUTICAL, LLC 59923 AREVA PHARMACEUTICALS 00065 ALCON LABORATORIES, INC. 76189 ARIAD PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 00998 ALCON LABORATORIES, INC. 24486 ARISTOS PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. -

Rebateable Manufacturers

Rebateable Labelers – July 2021 Manufacturers are responsible for updating their eligible drugs and pricing with CMS. Montana Healthcare Programs will not pay for an NDC not updated with CMS. Note: Some manufacturers on this list may have some NDCs that are covered and others that are not. Manufacturer ID Manufacturer Name 00002 ELI LILLY AND COMPANY 00003 E.R. SQUIBB & SONS, LLC. 00004 HOFFMANN-LA ROCHE 00006 MERCK & CO., INC. 00007 GLAXOSMITHKLINE 00008 WYETH PHARMACEUTICALS LLC, 00009 PHARMACIA AND UPJOHN COMPANY LLC 00013 PFIZER LABORATORIES DIV PFIZER INC 00015 MEAD JOHNSON AND COMPANY 00023 ALLERGAN INC 00024 SANOFI-AVENTIS, US LLC 00025 PFIZER LABORATORIES DIV PFIZER INC 00026 BAYER HEALTHCARE LLC 00032 ABBVIE INC. 00037 MEDA PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 00039 SANOFI-AVENTIS, US LLC 00046 WYETH PHARMACEUTICALS INC. 00049 ROERIG 00051 ABBVIE INC 00052 ORGANON USA INC. 00053 CSL BEHRING L.L.C. 00054 HIKMA PHARMACEUTICAL USA, INC. 00056 BRISTOL-MYERS SQUIBB PHARMA CO. 00065 ALCON LABORATORIES, INC. 00068 AVENTIS PHARMACEUTICALS 00069 PFIZER LABORATORIES DIV PFIZER INC 00071 PARKE-DAVIS DIV OF PFIZER 00074 ABBVIE INC 00075 AVENTIS PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 00078 NOVARTIS 00085 SCHERING CORPORATION 00087 BRISTOL-MYERS SQUIBB COMPANY 00088 AVENTIS PHARMACEUTICALS 00093 TEVA PHARMACEUTICALS USA, INC. 00095 BAUSCH HEALTH US, LLC Page 1 of 19 Manufacturer ID Manufacturer Name 00096 PERSON & COVEY, INC. 00113 L. PERRIGO COMPANY 00115 IMPAX GENERICS 00116 XTTRIUM LABORATORIES, INC. 00121 PHARMACEUTICAL ASSOCIATES, INC. 00131 UCB, INC. 00132 C B FLEET COMPANY INC 00143 HIKMA PHARMACEUTICAL USA, INC. 00145 STIEFEL LABORATORIES, INC, 00168 E FOUGERA AND CO. 00169 NOVO NORDISK, INC. 00172 TEVA PHARMACEUTICALS USA, INC 00173 GLAXOSMITHKLINE 00178 MISSION PHARMACAL COMPANY 00185 EON LABS, INC.