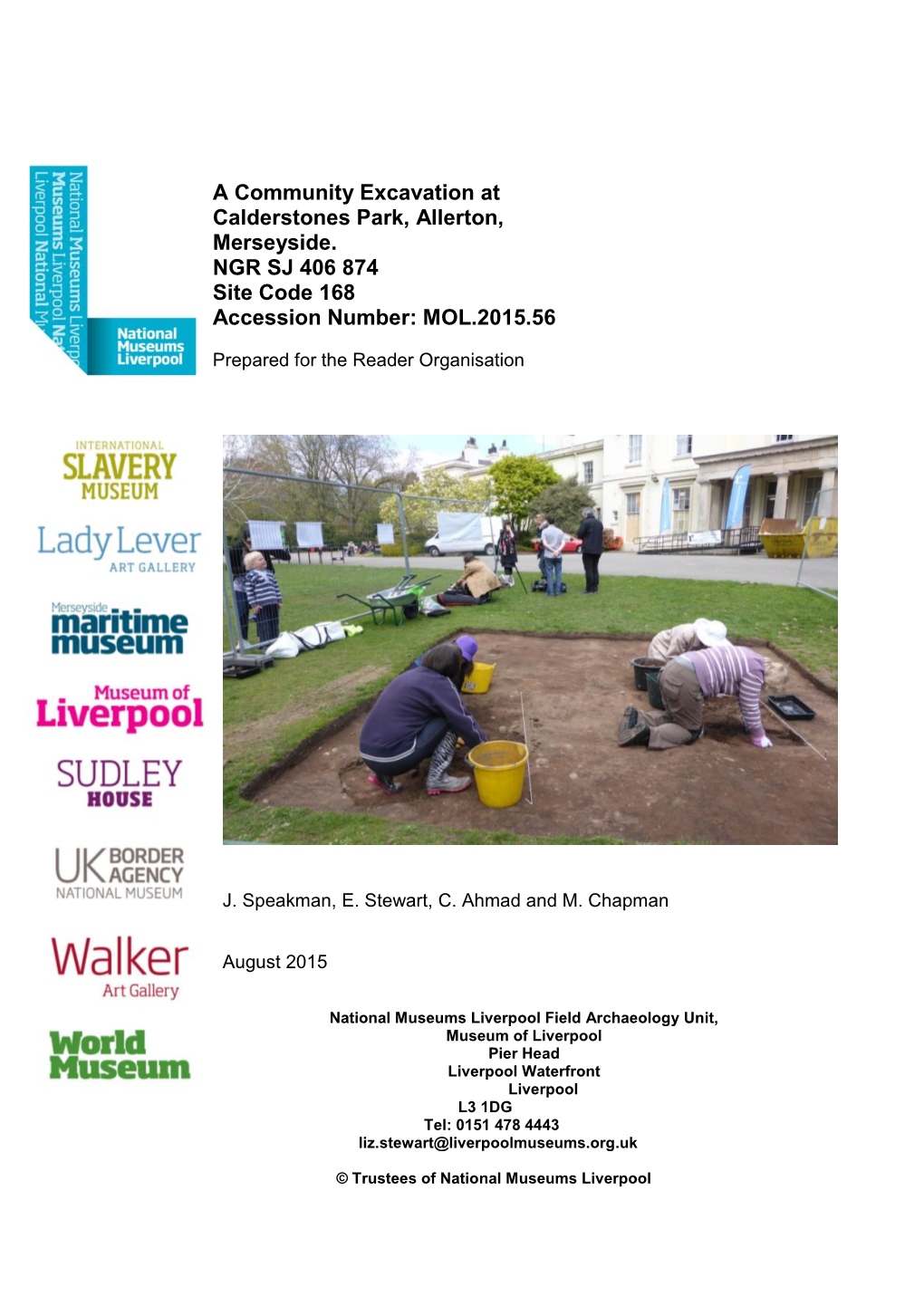

Calderstones Community Excavation Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Speke Cycle Route

www.LetsTravelWise.org 1253 330 0151 Telephone: need. might you else 090305/IS/TM/08O9/P anything and times, the through you talk will bike. by easily more Speke around get and person local a – 33 22 200 0871 travel to way wiser a is cycling how shows leaflet This future. our and us on Traveline call want, for move wise a is out them trying Merseyside, in options of lots have We Updated you train or bus which out find To Getting around Speke on your bike your on Speke around Getting September journey. each making of way Manchester. best the about think to need all we cities big other in seen pollution and and Widnes Warrington, in stations 2011. congestion the avoid to want we If slower. getting is travel car meaning Cycle Speke Cycle for outwards and Centre City the in MA. rapidly, rising is Merseyside in car by made being trips of number the Central Liverpool and Street Lime but journeys, their of many or all for TravelWise already are people Most Liverpool towards stations rail Cross Hunts and Parkway South Liverpool from both operate trains Line City and Northern Frequent Centre. City car. a without journeys make the to Parkway South Liverpool from minutes 15 to 10 about takes only It to everyone for easier it make to aim we Merseytravel, and Authorities Local Merseyside the by Funded sharing. car and transport public cycling, trains. Merseyside walking, more – travel sustainable more encourage to aims TravelWise all on free go Bikes problem. a be can parking where Centre City Liverpool into travelling when or workplace, your or school to get to easier it makes www.transpenninetrail.org.uk Web: This way. -

Change Places in Lancashire

For more information contact Accessible Changing Bill Nightingale Tel: 07814426712 Facilities in Lancashire Email: [email protected] The booklet contains Changing Places and other accessibility facilities known to the publisher in September 2014. Please tell us if you know of any Changing PlacesIN PARTNERSHIP WITH in Lancashire that are not on our list. If you find any of this information is Changing Places not correct, let us know and we will Locations and Accessibility update it. Information Changing Places Changing Places toilets provide: The right equipment Standard accessible toilets (disabled toilets) do not meet the needs of all people with a disability or ● A height adjustable changing the needs of their carers. Many people with bench profound and multiple learning disabilities need support to use the toilet, or require the use of a ● A tracking hoist system, or height adjustable changing bench where a carer can safely change their continence pad. mobile hoist Enough space They also need a hoisting system so they can be helped to transfer safely from their wheelchair to ● Adequate space in the changing the toilet or changing bench. area for the disabled person and up to two carers This booklet has been put together as a guide for Lancashire and surrounding areas. The content ● A centrally placed toilet with is true and accurate as of 15/09/2014. room either side for the carers ● A screen or curtain to allow the disabled person and carer some privacy A safe and clean environment ● Wide tear off paper roll to cover the bench Click on the name of the town to go to changing places in that area. -

Enquiries To: Information Team Our Ref: FOI553771

Enquiries to: Information Team Our Ref: FOI553771 [email protected] Dear Mr Barry, Freedom of Information Request 553771 Thank you for your recent request received 5th September 2017. Your request was actioned under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 in which you requested the following information – I would like to request a copy of the event document submitted to the Safety Advisory Group (SAG) and the membership list of the SAG, who Chairs the SAG, how much this event cost the City and out of which budget any cost was met. I would also request which departments were involved within the Council in this event and a list of any external partners, companies or agencies involved with this event. Response: Liverpool City Council confirms that it holds information relevant to the terms of your request, our responses being as follows – 1. A copy of the final Event Management Plan for this specific event is appended to this response and which provides the requested information (Appendix 1). 2. SAG attendees are listed on the minutes, copies of which being appended to this response (Appendix 2). 3. Two Regulatory Compliance Officers from the Licensing Authority attended on the morning of the event to check compliance with premises licence conditions only. Details of additional Officers present are set out within the report produced by The Event Safety Shop as a result of its Independent Inquiry, as commissioned by the City Council. Details of additional Council Officer attendees are as set out in the independent investigation report details of which are already in the public domain and which may be accessed via the following weblink – https://licensing.liverpool.gov.uk/PAforLalpacLIVE/1/LicensingActPremises/Search/34 96/Detail?LIC_ID=23111 4. -

Liverpool Historic Settlement Study

Liverpool Historic Settlement Study Merseyside Historic Characterisation Project December 2011 Merseyside Historic Characterisation Project Museum of Liverpool Pier Head Liverpool L3 1DG © Trustees of National Museums Liverpool and English Heritage 2011 Contents Introduction to Historic Settlement Study..................................................................1 Aigburth....................................................................................................................4 Allerton.....................................................................................................................7 Anfield.................................................................................................................... 10 Broadgreen ............................................................................................................ 12 Childwall................................................................................................................. 14 Clubmoor ............................................................................................................... 16 Croxteth Park ......................................................................................................... 18 Dovecot.................................................................................................................. 20 Everton................................................................................................................... 22 Fairfield ................................................................................................................. -

How to Get to Liverpool Hope University

Issue 1 Spring 2012 The Merseyside Transport Partnership Transport Merseyside The D E This guide has been funded by the Department of Transport through the Local Sustainable Transport Fund. www.LetsTravelWise.org L P C A Y P C E E R R P R N I (Hope Park) (Hope N O T E D University Liverpool Hope Liverpool www.LetsTravelWise.org to learn more. more. learn to www.LetsTravelWise.org How to get to to get to How adult cycle skills and maintenance training sessions. Visit sessions. training maintenance and skills cycle adult details of organised rides and local bike shops and free and shops bike local and rides organised of details including route maps covering the whole of Merseyside, of whole the covering maps route including There are many opportunities to help cyclists on their way, their on cyclists help to opportunities many are There and lockers. lockers. and the locations of local train stations and cycle shelters shelters cycle and stations train local of locations the on the frequency of bus routes is displayed, along with with along displayed, is routes bus of frequency the on cycling options available at Hope Park campus. Information campus. Park Hope at available options cycling This guide shows all public transport and recommended and transport public all shows guide This you money. you journey a week helps to improve fitness and could save save could and fitness improve to helps week a journey Using public transport, walking or cycling for just one just for cycling or walking transport, public Using The campus is situated in a leafy suburb of Liverpool just four miles from the city centre, where traditional architecture sits beside contemporary buildings and facilities Liverpool Hope University wants to improve access to make it easier to travel to and from our campuses. -

The Boundary Committee for England

OAK HILL PARK School E RIV OLD SWAN WARD T D F S MA O HO T M R C I L Y L E E L D N A G O N E L T E A N S KNOTTY ASH WARD E D E R V IV I E R THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND D S N E BROAD M 6 E 2 U Q GREEN BOW OAK VALE RING PERIODIC ELECTORAL REVIEW OF LIVERPOOL PAR K RD OAD COURT HEY PARK RK R G PA WRIN M 62 BO Final Recommendations for Ward Boundaries in Liverpool City March 2003 LIVERPOOL Sheet 3 of 3 King George V Memorial Field Recreation OLIVE Ground AD N MOUNT RO O ELL R VER T C DE H H E W L A W Y O O D A V E Sheet 3 N S U "This map is reproduced from the OS map by The Electoral Commission 1 O E C U y T cle with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. H D T A r W RO a LL ck Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. A WA Y ING TH Licence Number: GD03114G" Q U E E N S 2 3 Schools D R I Playing Field School V School E W A V E Childwall R T Comprehensive R WAVERTREE WARD E CHILDWALL WARD School E S c Playing Field o re L a n e Und G CH a ILD rd WA e LL R n OAD s CHILDWALL VE RI School D LD IE WAVERTREE SF B R The King David O GREEN E YL A High School A Childwall Golf Course U N C L A I R Council D R Offices I V E Ashfield School C H IL D W A L L L A N E Our Lady of AD RO The Assumption D EL FI RC Junior School TH EA H WO Liverpool Hope Wheathills Industrial OL TON University School Estate RO Belle Vale Shopping Centre AD College Hope Park Church BELLE VALE WARD School Primary School School Lee Park Golf Course H School O R N -

A Vision for Tennis in Liverpool (Draft)

A VISION FOR TENNIS IN LIVERPOOL (DRAFT) Produced by the Liverpool Tennis Steering Group, in co-operation with the Tennis Clubs of the City of Liverpool. The draft of this document is designed to be considered by the Tennis Clubs of Liverpool and other interested parties by way of an open process of consultation. 1. Background: The Liverpool and District Tennis Steering Group was set up between June and October 2016 at the behest of the Tennis Clubs of the City of Liverpool. Two stake-holder meetings were held at Liverpool Cricket Club at which representatives of the clubs came to the conclusion that a representative group was needed to develop a Vision and Strategy for tennis in the City and to bring forward a range of actions to ensure that fragmentation among the various aspects of tennis provision was overcome. From its outset the LDTSG benefitted from a substantial grant from the Liverpool Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG.) It was agreed to include a range of representatives to sit on the LDTSG who would speak on behalf of the “family” of tennis in Liverpool. The current representatives are: Representing the Liverpool Tennis League: Jamie Semple Representing the Lancashire LTA: Mike McBrien Representing Schools: Tony McKee Representing the Liverpool City Council: Chris Caskie Representing Community Tennis: David Hardman Representing the Merseyside Sports Partnership: Andrew Wileman Representing Coaches: David Simms Representing the LTA: Allison Lewis. Once the Committee met it determined the following persons should act as officers to carry out the administration of the committee: Chair: Tony McKee Vice-Chair: Mike McBrien Secretary: Allison Lewis. -

Guide to Family Activities

Guide to Family Activities Liverpool Football Club – one of the most successful clubs in the world, LFC is a truly international club. Whether a football fan or not, the Anfield Stadium tour gives a unique insight into the club’s dazzling history. Visitors will see the dressing rooms, press room, trophy room as well as walk out under the famous ‘This is Anfield’ sign to view the magnificent pitch. Underwater Street – a zoned activity and discovery centre where children can explore, play and learn. Let your little ones experience the sensory area, the lab, the imagination village, physical zone, construction area or art area Museums and Galleries – the World Museum, Maritime Museum, Walker Art Gallery, Tate Liverpool, and Museum of Liverpool all have children-friendly exhibits and activities. Check details to see special events for children. Free entry to all. Mersey Ferry – take the 50 minute River Explorer and learn more about the maritime history of Liverpool whilst taking in the view. Passengers also have the option to hop off the ferry to visit Spaceport, where children can blast off through space and time. Parks – Liverpool is well equipped with parks and coastal walks to help burn off some energy. Close to Liverpool city centre are Sefton Park, with its beautiful Victorian Glasshouse, and Calderstones Park, home to Liverpool International Tennis Tournament. Otterspool Prom in South Liverpool is also popular, with a play park, café and activity centre. Formby Nature Reserve – a short journey from Liverpool is the National Trust’s nature reserve at Freshfield, Formby. Look out for a Red Squirrel or try out your technical treasure hunt skills with geocaching. -

Court of Appeal Judgment Template

Neutral Citation Number: [2020] EWCA Civ 861 Case No: C1/2019/0388 IN THE COURT OF APPEAL (CIVIL DIVISION) ON APPEAL FROM THE ADMINISTRATIVE COURT PLANNING COURT MR JUSTICE KERR [2019] EWHC 55 (Admin) Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 9 July 2020 Before: Lady Justice Rafferty Lord Justice Lindblom and Lord Justice Newey - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between: R. (on the application of Liverpool Open and Green Respondent Spaces Community Interest Company) - and - Liverpool City Council Appellant - and - (1) Redrow Homes Ltd. Interested (2) Arthur Brooks (on behalf of the Merseyside Live Parties Steam and Model Engineers) - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Mr Paul Tucker Q.C. and Ms Constanze Bell (instructed by Liverpool City Council Legal Services) for the Appellant Mr Ned Westaway and Mr Charles Streeten (instructed by E. Rex Makin & Co Solicitors) for the Respondent The Interested Parties did not appear and were not represented. Hearing date: 19 May 2020 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Judgment Approved by the court for handing down (subject to editorial corrections) Covid-19 Protocol: This judgment was handed down remotely by circulation to the parties’ representatives by email, release to BAILII and publication on the Courts and Tribunals Judiciary website. The date and time for hand-down is deemed to be 1630 on Thursday, 9 July 2020. Judgment Approved by the court for handing down R. (on the application of Liverpool Open and Green Spaces (subject to editorial corrections) Community -

Celluloid Hitler's Thedevil Inferno Hellmouth Instereo

THE 'IT' FACTOR REVOLUTION IN THE HEAD INSIDE PUTIN'S VIRTUAL RUSSIA SINISTER CLOWNS SPREAD GOING UNDERGROUND UNCOVERING A TUNNEL TO HADES TERROR ACROSS THE USA CRYING WOLF CHILDREN ABDUCTED BY ANIMALS FT346 NOVEMBER 2016 £4.25 CELLULOID HITLER'S THE DEVIL INFERNO HELLMOUTH IN STEREO BRINGING HELL TO THE DARK SECRETS THE AMAZING ART THE SILVER SCREEN OF HRAD HOUSKA OF THE DIABLERIES Fortean Times 346 strange days Rains of meat, catfish from the sky, creepy clowns, attack of the sea potatoes, world’s oldest people, signals from space, self-immolating ancients, EU aliens, pioneer potheads and CONTENTS early brewers, the lost city that wasn’t – and much more. 05 THE CONSPIRASPHERE 22 NECROLOG 14 ARCHAEOLOGY 23 FAIRIES & FORTEANA the world of strange phenomena 15 CLASSICAL CORNER 24 FLYING SORCERY 16 SCIENCE 25 UFO CASEBOOK features COVER STORY 26 DIABLERIES: THE DEVIL IN 3-D In the 19th century, Paris was overtaken by a new sensation – stereoscopic cards in which the Devil and all his works were shown in astonishing, and often humourously satirical, detail. BRIAN MAY tells how he fell under their diabolical spell and with fellow fi ends DENIS PELLERIN & PAULA FLEMING explores the technological and cultural background of these hellish creations. 32 A VISIT TO THE UNDERWORLD MIKE DASH examines the unsolved mystery of the tunnels at Baia. Did ancient priests fool visitors to a sulphurous NDON STEREOSCOPIC COMPANY subterranean stream into believing that they had crossed LO 26 THE DEVIL IN 3-D the River Styx and entered Hades? The diabolical pleasures of the ‘Diableries’ stereoscopic cards 38 DARKNESS VISIBLE: HELL IN THE CINEMA Ever since the silent era, fi lmmakers have been putting their visions of Hell on the silver screen, and much of their inspiration derives from a 14th century Italian poet and a 19th century French artist. -

Strategic Green and Open Spaces Review Board

Submission Document SD20 Strategic Green and Open Spaces Review Board Final Report 2016 A city becomes magnificent when the spaces between the buildings equal the architecture they frame Contents Mayoral Preface .................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Chair’s Note ........................................................................................................................................................................ 8 1. The Strategic Green and Open Spaces Review Board ............................................................................................... 9 Board Members .................................................................................................................................................................................. 9 2. Overview and Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 13 Background and Context ................................................................................................................................................................. 13 Time of Austerity .............................................................................................................................................................................. 13 The Review ...................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Questionnaire Report.Pub

Liverpool Parks and Open Spaces Project 2006 Pilot Survey Report Newsham Park User Questionnaire 1 Contents Page No. Part One: Introduction 3 Part Two: Survey 4 I Methodology 4 i. Selection of the site ii. Questionnaire model iii. Circulation and collection II Reponses and Results 7 III Conclusion 16 i. Question breakdown ii. Recurrent issues/themes/concerns iii. Potential future research Part Three: Viability Assessment 19 i. Circulation, accessibility and collection ii. Identification iii. Other 2 Part One: Introduction Liverpool’s Parks The history of parks and open spaces in Liverpool, to a large extent mirrors the national ,picture. In 1833, the Select Committee on Public Walks emphasised the need to provide accessible space for recreation to improve the health of the urban population, to diffuse social tensions, and to create meeting places where 'the classes could learn from each other' (Conway, 1991, pp.3, 5). This challenge was taken up initially by the Commissioners for the Improvement of Birkenhead, with the opening of the first fully municipal park in 1847 designed by Joseph Paxton. An ambitious plan for a ring of nine separate parks around Liverpool was drawn up by H.P. Homer in 1850, but cost considerations restricted development to Wavertree (1856) and Shiel Park (1862). Only after the Liverpool Improvement Act of 1865 were key elements of the original plan finally realised with the opening of Newsham (1868), Stanley (1870) and Sefton (1872) parks, which represented truly public access to open space. Both the range and nature of open space provision changed significantly in the course of the twentieth century.