86 Sugar Creek Through 98 Yurok

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Bibliography of Klamath Mountains Geology, California and Oregon

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY A bibliography of Klamath Mountains geology, California and Oregon, listing authors from Aalto to Zucca for the years 1849 to mid-1995 Compiled by William P. Irwin Menlo Park, California Open-File Report 95-558 1995 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards (or with the North American Stratigraphic Code). Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. PREFACE This bibliography of Klamath Mountains geology was begun, although not in a systematic or comprehensive way, when, in 1953, I was assigned the task of preparing a report on the geology and mineral resources of the drainage basins of the Trinity, Klamath, and Eel Rivers in northwestern California. During the following 40 or more years, I maintained an active interest in the Klamath Mountains region and continued to collect bibliographic references to the various reports and maps of Klamath geology that came to my attention. When I retired in 1989 and became a Geologist Emeritus with the Geological Survey, I had a large amount of bibliographic material in my files. Believing that a comprehensive bibliography of a region is a valuable research tool, I have expended substantial effort to make this bibliography of the Klamath Mountains as complete as is reasonably feasible. My aim was to include all published reports and maps that pertain primarily to the Klamath Mountains, as well as all pertinent doctoral and master's theses. -

Modeling Insolation, Multi-Spectral Imagery and Lidar Point-Cloud Metrics to Predict Plant Diversity in a Temperate Montane Forest

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 3 August 2021 doi:10.20944/preprints202108.0078.v1 Article Modeling Insolation, Multi-spectral Imagery and LiDAR Point-cloud Metrics to Predict Plant Diversity in a Temperate Montane Forest Paul Dunn 1,* and Leonhard Blesius 2 1 Department of Geography and Environment, San Francisco State University; [email protected] 2 Department of Geography and Environment, San Francisco State University; [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed. Abstract: Incident solar radiation (insolation) passing through the forest canopy to the ground sur- face is either absorbed or scattered. This phenomenon, known as radiation attenuation, is measured using the extinction coefficient (K). The amount of radiation at the ground surface of a given site is effectively controlled by the canopy’s surface and structure, determining its suitability for plant species. Menhinick’s and Simpson biodiversity indexes were selected as spatially explicit response var- iables for the regression equation using canopy structure metrics as predictors. Independent varia- bles include modeled area solar radiation, LiDAR derived canopy height, effective leaf area index data derived from multi-spectral imagery, and canopy strata metrics derived from LiDAR point- cloud data. The results support the hypothesis that, 1.) canopy surface and strata variability may be associated with understory species diversity due to habitat partitioning and radiation attenuation, and that, 2.) such a model can predict both this relationship and biodiversity clustering. The study data yielded significant correlations between predictor and response variables and was used to produce a multiple-linear model comprising canopy relief, texture of heights, and veg- etation density to predict understory plant diversity. -

9691.Ch01.Pdf

© 2006 UC Regents Buy this book University of California Press, one of the most distinguished univer- sity presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2006 by The Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sawyer, John O., 1939– Northwest California : a natural history / John O. Sawyer. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-23286-0 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Natural history—California, Northern I. Title. QH105.C2S29 2006 508.794—dc22 2005034485 Manufactured in the United States of America 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 10987654321 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum require- ments of ansi/niso z/39.48-1992 (r 1997) (Permanence of Paper).∞ The Klamath Land of Mountains and Canyons The Klamath Mountains are the home of one of the most exceptional temperate coniferous forest regions in the world. The area’s rich plant and animal life draws naturalists from all over the world. Outdoor enthusiasts enjoy its rugged mountains, its many lakes, its wildernesses, and its wild rivers. Geologists come here to refine the theory of plate tectonics. Yet, the Klamath Mountains are one of the least-known parts of the state. The region’s complex pattern of mountains and rivers creates a bewil- dering set of landscapes. -

Vegetation Descriptions NORTH COAST and MONTANE ECOLOGICAL PROVINCE

Vegetation Descriptions NORTH COAST AND MONTANE ECOLOGICAL PROVINCE CALVEG ZONE 1 December 11, 2008 Note: There are three Sections in this zone: Northern California Coast (“Coast”), Northern California Coast Ranges (“Ranges”) and Klamath Mountains (“Mountains”), each with several to many subsections CONIFER FOREST / WOODLAND DF PACIFIC DOUGLAS-FIR ALLIANCE Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) is the dominant overstory conifer over a large area in the Mountains, Coast, and Ranges Sections. This alliance has been mapped at various densities in most subsections of this zone at elevations usually below 5600 feet (1708 m). Sugar Pine (Pinus lambertiana) is a common conifer associate in some areas. Tanoak (Lithocarpus densiflorus var. densiflorus) is the most common hardwood associate on mesic sites towards the west. Along western edges of the Mountains Section, a scattered overstory of Douglas-fir often exists over a continuous Tanoak understory with occasional Madrones (Arbutus menziesii). When Douglas-fir develops a closed-crown overstory, Tanoak may occur in its shrub form (Lithocarpus densiflorus var. echinoides). Canyon Live Oak (Quercus chrysolepis) becomes an important hardwood associate on steeper or drier slopes and those underlain by shallow soils. Black Oak (Q. kelloggii) may often associate with this conifer but usually is not abundant. In addition, any of the following tree species may be sparsely present in Douglas-fir stands: Redwood (Sequoia sempervirens), Ponderosa Pine (Ps ponderosa), Incense Cedar (Calocedrus decurrens), White Fir (Abies concolor), Oregon White Oak (Q garryana), Bigleaf Maple (Acer macrophyllum), California Bay (Umbellifera californica), and Tree Chinquapin (Chrysolepis chrysophylla). The shrub understory may also be quite diverse, including Huckleberry Oak (Q. -

California Floras, Manuals, and Checklists: a Bibliography

Humboldt State University Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University Botanical Studies Open Educational Resources and Data 2019 California Floras, Manuals, and Checklists: A Bibliography James P. Smith Jr Humboldt State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Smith, James P. Jr, "California Floras, Manuals, and Checklists: A Bibliography" (2019). Botanical Studies. 70. https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps/70 This Flora of California is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources and Data at Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Botanical Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CALIFORNIA FLORAS, MANUALS, AND CHECKLISTS Literature on the Identification and Uses of California Vascular Plants Compiled by James P. Smith, Jr. Professor Emeritus of Botany Department of Biological Sciences Humboldt State University Arcata, California 21st Edition – 14 November 2019 T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S Introduction . 1 1: North American & U. S. Regional Floras. 2 2: California Statewide Floras . 4 3: California Regional Floras . 6 Northern California Sierra Nevada & Eastern California San Francisco Bay, & Central Coast Central Valley & Central California Southern California 4: National Parks, Forests, Monuments, Etc.. 15 5: State Parks and Other Sites . 23 6: County and Local Floras . 27 7: Selected Subjects. 56 Endemic Plants Rare and Endangered Plants Extinct Aquatic Plants & Vernal Pools Cacti Carnivorous Plants Conifers Ferns & Fern Allies Flowering Trees & Shrubs Grasses Orchids Ornamentals Weeds Medicinal Plants Poisonous Plants Useful Plants & Ethnobotanical Studies Wild Edible Plants 8: Sources . -

Vascular Plants of the Russian Peak Area Siskiyou County, California James P

Humboldt State University Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University Botanical Studies Open Educational Resources and Data 2-2004 Vascular Plants of the Russian Peak Area Siskiyou County, California James P. Smith Jr Humboldt State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Smith, James P. Jr, "Vascular Plants of the Russian Peak Area Siskiyou County, California" (2004). Botanical Studies. 34. http://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps/34 This Flora of Northwest California: Checklists of Local Sites of Botanical Interest is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources and Data at Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Botanical Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VASCULAR PLANTS OF THE RUSSIAN PEAK AREA SISKIYOU COUNTY, CALIFORNIA Edited by John O. Sawyer, Jr. & James P. Smith, Jr. Professor Emeritus of Botany Department of Biological Sciences Humboldt State University Arcata, California 18 February 2004 Russian Peak (elevation 8196 ft.) is located in the Salmon Mountains, about 12.5 miles south-southwest FLOWERING PLANTS of Etna. It is the highest peak in the Russian Wilderness. The Salmon Mountains are a subunit of Aceraceae the Klamath Mountains. The area is famous for its Acer glabrum var. torreyi diversity of conifer species and for the discovery of the subalpine fir in California, based on the field work Apocynaceae of John Sawyer and Dale Thornburgh. Apocynum androsaemifolium FERNS Berberidaceae Mahonia dictyota Equisetaceae Mahonia nervosa var. -

86. Sugar Creek (Keeler-Wolf 1984D, 1989F, Sawyer and Thornburgh 1971) Location This Candidate RNA Is on the Klamath National Forest

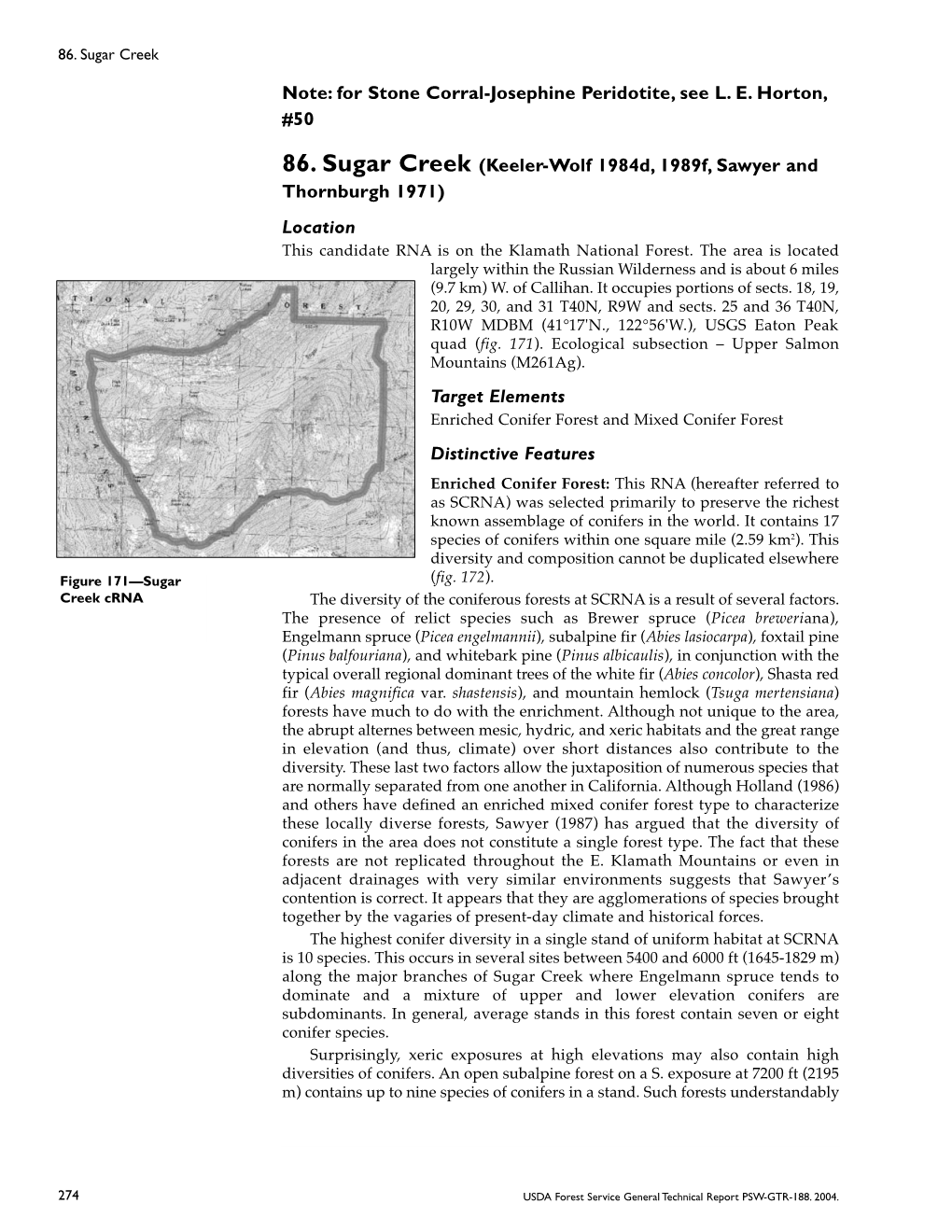

86. Sugar Creek (Keeler-Wolf 1984d, 1989f, Sawyer and Thornburgh 1971) Location This candidate RNA is on the Klamath National Forest. The area is located largely within the Russian Wilderness and is about 6 miles (9.7 km) W. of Callihan. It occupies portions of sects. 18, 19, 20, 29, 30, and 31 T40N, R9W and sects. 25 and 36 T40N, R10W MDBM (41°17'N., 122°56'W.), USGS Eaton Peak quad (fig. 171). Ecological subsection – Upper Salmon Mountains (M261Ag). Target Elements Enriched Conifer Forest and Mixed Conifer Forest Distinctive Features Enriched Conifer Forest: This RNA (hereafter referred to as SCRNA) was Figure 171— selected primarily to preserve the richest known assemblage of conifers in the Sugar Creek world. It contains 17 species of conifers within one square mile (2.59 km2). This cRNA diversity and composition cannot be duplicated elsewhere (fig. 172). The diversity of the coniferous forests at SCRNA is a result of several factors. The presence of relict species such as Brewer spruce (Picea breweriana), Engelmann spruce (Picea engelmanii), subalpine fir (Abies lasiocarpa), foxtail pine (Pinus balfouriana), and whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis), in conjunction with the typical overall regional dominant trees of the white fir (Abies concolor), Shasta red fir (Abies magnifica var. shastensis), and mountain hemlock (Tsuga mertensiana) forests have much to do with the enrichment. Although not unique to the area, the abrupt alternes between mesic, hydric, and xeric habitats and the great range in elevation (and thus, climate) over short distances also contribute to the diversity. These last two factors allow the juxtaposition of numerous species that are normally separated from one another in California. -

Special Areas Report

APPENDIX F - Special Areas Report Within the Callahan Watershed are two specially tation and enjoyment. A site-specific management designated areas which are under special plan has not been completed for this SIA. management direction in the Klamath National Forest CONIFER SPECIES Land and Resource Management Plan (Forest Plan). These are the proposed Sugar Creek Research TRUE FIRS Natural Area (RNA) and the Duck Lakes Botanical Abies amabilis Pacific silver fir Special Interest Area (SIA). Except for a small sliver *Abies concolor white fir of the Sugar Creek RNA, both areas are within the *Abies lasiocarpa subalpine fir Russian Wilderness. Abies magnifica red fir *Abies magnifica var. shastensis Shasta red fir The unique value of these areas is the remarkable Abies procera noble fir conifer species diversity they contain. The Sugar Abies magnifica x procera red fir x noble fir Creek and Duck Lake Creek drainages and mountains Abies concolor x grandis white fir x grand fir contain the richest assemblage of conifers in the world; 17 species within one square mile. This conifer CYPRESS FAMILY diversity is the result of several factors. A number of *Calocedrus decurrens incense-cedar species are believed to be relicts of the last glacial Chamaecyparis lawsoniana Port-Orford-cedar period, where they occur on Russian Peak (8,200 Chamaecyparis nootkatensis Alaska yellow cedar feet) and several ridgetop sites over 7,600 feet. The Cupressus bakeri Baker cypress deep glacial valleys 2,000 feet below these sites *Juniperus communis common juniper create a wide range of elevations and associated Juniperus occidentalis western juniper climates and habitats. -

Subalpine Forests

TWENTY-EIGHT Subalpine Forests CONSTANCE I. MILLAR and PHILIP W. RUNDEL Introduction Subalpine forests in California, bounded by the treeline at their upper limit at the alpine-treeline ecotone. Treeline has their upper margin, are the forest zone influenced primar long fascinated ecologists for its predominance worldwide, ily by abiotic controls, including persistent snowpack, desic from equatorial tropical forests to polar zones. While many cating winds, acute and chronic extreme temperatures, soil environmental factors mediate the exact location of regional moisture and evapotranspirative stresses in both summer treelines—a “devil-is-in-the-details” that also delights ecolo and winter, and short growing seasons (Fites-Kaufman et al. gists—a robust unifying theory has been developed to explain 2007). Subalpine forest species derive their annual precipita the treeline ecotone as the thermal contour (isotherm) on tion primarily in the form of snow. Disturbances such as fire, the landscape where average growing-season temperature is and biotic interactions including competition, are less impor 6.4°C (Körner and Paulsen 2004, Körner 2012). In this context tant than in montane forests. Although some subalpine for “trees” are defined as plants having upright stems that attain ests are dense and have closed canopies, most are more accu height ≥3 meters regardless of taxonomy, and “forest” is char rately considered woodlands, with short-statured individuals acterized as more-or-less continuous patches of trees whose and wide spacing of young as well as old trees. Subalpine for crowns form at least a loose canopy (Körner 2007). Although est stands are commonly interrupted by areas of exposed bed not without some controversy, the hypothesized mechanism rock, snowfields, and upland herbaceous and shrub types— behind the global treeline isotherm relates to the fact that the latter comprising important components of broader upright trees are more closely coupled with the atmosphere subalpine ecosystems (Figure 28.1; Rundel et al. -

Pacific Crest Trail Distance: 221 Miles One Way Conifer Count: 19 Sections P, Q, and R Difficulty: Extremely Strenuous

Pacific Crest Trail Distance: 221 Miles one way Conifer Count: 19 Sections P, Q, and R Difficulty: Extremely Strenuous 0 10 Kilometers etting there: This trek is described r e v 0 10 Miles i Ashland for the length of the PCT through R G e the Klamath Mountains—from Inter- t a g state 5 at Castle Crags State Park in e common l p California to interstate 5 at Siskiyou p juniper A Summit in Oregon. The route can be R hiked from north to south or south Red Buttes Oregon Wilderness Soda Mountain to north. The advantage to either re- Siskiyou Pacific ally lies in your interests in hiking with cypress silver fir Wilderness r other people. About 300 people will be Klamath Rive Seiad Valley streaming along (south to north) in July on their way from Mexico to Canada attempting the entire 2650 miles of the route. If you want to meet up with other hikers and talk trail, this might be your Sc ott R route. In the fall, you will mostly likely iver have it to yourself most of the way. Q hy go? The Big Bend is botani- Marble subalpine fir Wcally interesting. This is due to Mountain the unique geology and climate offered Wilderness as the trail swings westward to the Etna foxtail pine ocean and onto the complex soils of the Engelmann spruce Klamath Mountains. The trail also offers whitebark Mount 6 designated wilderness areas and many Brewer spruce pine Shasta more miles of undesignated wild land. 14,179 If you have the stamina and the time, it Russian Port Orford- Wilderness P cedar is surely one of the greatest segments of the Pacific Crest Trail. -

Humboldt State University Herbarium

HUMBOLDT STATE UNIVERSITY HERBARIUM CALIFORNIA FLORAS: LITERATURE ON THE IDENTIFICATION AND USES OF CALIFORNIA VASCULAR PLANTS Compiled by James Payne Smith, Jr. Professor of Botany, Emeritus Department of Biological Sciences Humboldt State University Arcata, California MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATION NO. 1 (17th Edition) 10 November 2010 T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S Introduction ........................................................................................... 1 1: Regional and Statewide Floras North America & United States ....................................................... Western United States .................................................................... Statewide ........................................................................................ 2: California Regional Floras Northern California ..................................................................... 7 Sierra Nevada & Eastern California ............................................... 9 San Francisco Bay, & Central Coast .............................................. 9 Central Valley & Central California ............................................. 11 Southern California ................................................................... 12 3: National Forests, Parks, Monuments, & Reserves ...................... 15 4: State Parks, Beaches, & Historic Sites ........................................ 23 5: County and Local Floras .............................................................. 26 6: Selected Plant Groups Ferns & Fern Allies ................................................................... -

Inferring Bedrock Uplift in the Klamath Mountains Province from River Profile Analysis and Digital Topography

Inferring bedrock uplift in the Klamath Mountains Province from river profile analysis and digital topography By Timothy Kirt Anderson, B.A., B.S. A Thesis In Geosciences Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Degree of Masters of Science Approved Dr. Aaron Yoshinobu Chairperson of the Committee Dr. Calvin Barnes Dr. David Leverington Accepted Fred Hartmeister Dean of Graduate School December, 2008 Texas Tech University, Timothy Anderson, December 2008 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Aaron Yoshinobu for the opportunity to work on an exciting project, and am grateful for his enthusiastic approach to science. I would like to thank my committee members, Dr. Cal Barnes and Dr. David Leverington, for their thoughtful reviews of this manuscript. I would like to thank Dr. Jeff Lee and Linda Jones of the Department of Economics and Geography for the role they played in my financial support as a teaching assistant. I would like to acknowledge the Department of Geography and Dr. Yoshinobu for allowing me access to the hardware and software necessary to undertake this research. I would like to thank Dr. Don Elder for providing me with his ‘latest and greatest’ digital data of the Klamath Mountains. Finally, I’d like to thank my friends and family for their understanding, support, encouragement, and willingness to listen to my ideas. ii Texas Tech University, Timothy Anderson, December 2008 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ii Abstract v List of Figures vi List of Acronyms xii Chapter 1. Introduction 1 2. Tectonic Setting of the KMP and its Geologic History 10 2.1.