Sample Pages Sample Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[Wirral] Seacombe Ferry Terminal](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6648/wirral-seacombe-ferry-terminal-206648.webp)

[Wirral] Seacombe Ferry Terminal

Pier Head Ferry Terminal [Liverpool] Mersey Ferries, Pier Head, Georges Parade, Liverpool L3 1DR Telephone: 0151 227 2660 Fax: 0151 236 2298 By Car Leave the M6 at Junction 21a, and take the M62 towards Liverpool. Follow the M62 to the end, keeping directly ahead for the A5080. Continue on this road until it merges into the A5047, following signs to Liverpool City Centre, Albert Dock and Central Tourist Attractions. Pier Head Ferry Terminal is signposted from the city centre. Parking Pay and display parking is available in the Albert Dock and Kings Dock car parks. Pier Head Ferry Terminal is approximately 5-10 minutes walk along the river. By Public Transport Using Merseyrail’s underground rail service, alight at James Street Station. Pier Head Ferry Terminal is a 5- minute walk from James Street. For further information about bus or rail links contact Merseytravel on: 0870 608 2 608 or log onto: www.merseytravel.gov.uk By National Rail Lime Street Station is Liverpool’s main national rail terminus, with main line trains to and from Manchester, London, Scotland and the rest of the UK. Pier Head Ferry Terminal is a 20-minute walk from Lime Street [see tourist information signs]. Enquire at Queen Square Tourist Information Centre for details of bus services to Pier Head. Woodside Ferry Terminal [Wirral] Mersey Ferries, Woodside, Birkenhead, Merseyside L41 6DU Telephone: 0151 330 1472 Fax: 0151 666 2448 By Car From the M56 westbound, turn right onto the M53 at Junction 11. Follow the M53 motorway to Junction 1, and then take the A5139 [Docks Link/ Dock Road]. -

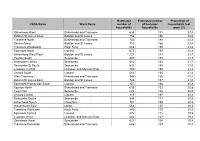

Full List As Proportion of Households

Estimated Estimated number Proportion of LSOA Name Ward Name number of of fuel poor households fuel households households poor (%) Birkenhead West Birkenhead and Tranmere 695 191 27.5 Bidston St James West Bidston and St James 756 186 24.6 Tranmere North Birkenhead and Tranmere 740 180 24.3 Bidston Moss Bidston and St James 710 166 23.4 Tranmere Woodward Rock Ferry 686 159 23.2 Egremont North Liscard 677 150 22.2 Birkenhead West Float Bidston and St James 1,124 244 21.7 Poulton South Seacombe 807 175 21.7 Seacombe Library Seacombe 682 148 21.7 Seacombe St Pauls Seacombe 692 149 21.5 Leasowe Central Leasowe and Moreton East 700 150 21.4 Liscard South Liscard 683 146 21.4 West Tranmere Birkenhead and Tranmere 746 158 21.2 Bidston St James East Bidston and St James 748 157 21.0 Egremont Promenade South Liscard 807 168 20.8 Egerton North Birkenhead and Tranmere 636 132 20.8 Town Hall Seacombe 672 138 20.5 Liscard Central Liscard 819 167 20.4 Seacombe Docks Seacombe 844 171 20.3 Birkenhead South Claughton 784 159 20.3 Woodchurch East Upton 664 135 20.3 Tranmere Well Lane Rock Ferry 840 170 20.2 Egremont Central Liscard 572 114 19.9 Leasowe West Leasowe and Moreton East 642 127 19.8 Seacombe West Seacombe 627 124 19.8 Tranmere Parklands Birkenhead and Tranmere 696 137 19.7 Estimated Estimated number Proportion of LSOA Name Ward Name number of of fuel poor households fuel households households poor (%) Egremont West Liscard 651 128 19.7 Egremont South Seacombe 701 134 19.1 Beechwood North Bidston and St James 637 121 19.0 Bidston Hill North -

WALK 1 Bidston Hill & River Fender

Information WALK 1 Bidston Hill & River Fender WALK 2 The Wonders of Birkenhead This Walk and Cycle leaflet for Wirral covers the north eastern quarter and is one of a series of A circular walk starting at the Tam O’Shanter 2a Turn left onto Noctorum Lane. Follow this grows in the shallow sandy soils. Follow the main path Birkenhead has some fascinating historical traffic lights and turn left into Ivy Street, following 7 From the Transport Museum retrace your steps four leaflets each consisting of three walks and Urban Farm, this route takes you across Wirral unsurfaced lane to the junction with Budworth Road. along this natural Sandstone Pavement. The Windmill attractions and if you haven’t yet discovered the Birkenhead Priory sign on your right. Birkenhead back to Pacific Road where there is the Pacific Road one cycle route. Cross with care as there is a blind bend to the right. should now be coming into view. Priory is at the end of Priory Street on the left. This Arts Centre and on towards the river to view the Ladies Golf Course, along the River Fender and Continue along Noctorum Lane past Mere Bank on the them you may be pleasantly surprised. This walk former Benedictine monastery has an exhibition and the is Mersey Tunnel Ventilation Tower. The architect who 8 Continue to the iron footbridge above the deep rocky I have recently updated all 12 walks based on back to the heights of Bidston Hill with views of right. Continue straight ahead. The track swings right visits ten of them. -

Mersey Ferries Group Guide Experience the Essence of Group Travel

Mersey Ferries group guide experience the essence of group travel Visit merseyferries.co.uk or call 0151 330 1444 COME ABOARD 4–5 6–7 8–9 FOR THE GREATEST GROUP DAYS OUT Mersey Ferries sail to Liverpool. Wirral. wider horizons A world class city of A wonderfully We can take your group a culture and fun different contrast lot further than you might Liverpool is putting on a Over on the other side of For every kind of group, great days out begin think. Our River Explorer whole new look with its the river, Wirral offers a Cruises give a unique view historic waterfront legacy complete contrast to all on the banks of the Mersey – with more reasons of Liverpool and Wirral, just a short walk away from that urban excitement. while our Manchester Ship the shopping paradise of Famed for its natural to visit than ever before. From the moment Canal Cruises take the scenic the smart new Liverpool beauty, it’s where visitors route right into the heart One centre. they arrive and the whole day through there’s of Manchester. flock to the landscaped Plus, all the attractions acres of Ness Botanic more to see, more to do and more to enjoy on that make this famous city gardens, and the an unforgettable trip. With so much to please such a tourist magnet for picturesque delights of Port visitors from all over the Sunlight garden village. everyone, no wonder it’s such a popular choice world – lots of lively streets And, where they discover to explore with a wealth of surprises like the unique for groups. -

Applied Business Inside Merseytravel Booklet

Inside Merseytravel and Mersey Ferries A Vocational Education Pack for Key Stage 4 Teachers’ Notes Promoting Business and Enterprise Education Merseytravel: a Business Organisation case study Unit 1: Investigating Business Portfolio Work Completed This unit considers what kind of organisation Merseytravel is and where its services are located. 1. Ownership 2. Aims and Objectives 3. Business Location 4. The Merseytravel organisation 5. The Personnel Division 6. The Operations Directorate 7. Customer Service 8. The information Services Division Unit 2: People and Business Portfolio Work Completed This unit describes the range of people who are involved with Merseytravel and how they interact with the organisation. 9. Stakeholders 10. Rights and responsibilities 11. Investigating job roles 12. Working arrangements 13. Training and development 14. Resolving disagreements 15. Recruitment and induction 16. Researching community views Unit 3: Business Finance Portfolio Work Completed This unit considers how Merseytravel uses its finance and maintains its records. 17. The flow of financial documents 18. Methods of making payments 19. Using a Revenue Budget 20. Breaking Even 21. Calculating profit or loss 22. Understanding a balance sheet 23. Financial planning 24. Sources of Finance Mersey Ferries: a Leisure and Tourism case stud Unit 1: Investigating Leisure & Tourism Portfolio Work Completed This unit shows the popularity of Mersey Ferries and its importance in the regional economy. 1. Welcome to Mersey Ferries 2. Mersey Ferries’ visitors 3. The customer passenger profile 4. The Business Plan 5. Mersey Ferries - a tourist attraction 6. Employment opportunities 7. Mersey Ferries and the local economy 8. Social, economic and environmental impact Unit 2: Marketing in Leisure & Tourism Portfolio Work Completed This unit introduces a variety of marketing methods used by Mersey Ferries to promote its business. -

East Wirral(Mersey Estuary)

River Mersey near to Eastham Country Park. East Wirral (Mersey Estuary) The East Wirral route takes you from the start of the Manchester Ship Canal on the banks of the River Mersey, into the woodlands of Eastham Country Park and through the area of industrial heritage of the east coast to Seacombe. Along the route you will pass near to the historic village of Port Sunlight, through the Victorian suburb of Rock Park, past Cammell Lairds Shipyard, and along to Woodside where you can see the world’s first rail tram system. 60 From Woodside Ferry Terminal and the U-boat Story you will pass the docks, the Twelve Quays Irish Ferry Terminal and on towards Seacombe, where you will find Spaceport and the best views of the Liverpool Waterfront World Heritage Site. The River Mersey was once renowned as a polluted river but now it’s not unusual to see seals, porpoise and dolphin in the Mersey. Charter fishing boats regularly pass from the Mersey to Liverpool Bay which has become one of the best inshore cod fishing grounds in north west Europe. 61 East Wirral (Mersey Estuary) Eastham Country Park 1 Eastham Country Park Eastham Country Park holds immense value and is a long- standing, major leisure and nature conservation area. It covers some 43 hectares and it is the last remaining substantial area of undeveloped land with public access on the Wirral bank of the River Mersey between Birkenhead and Ellesmere Port. Its location gives it particular importance as a local amenity, wildlife and educational resource. The site includes approximately 26 hectares of mature mixed deciduous woodland, 8 hectares of amenity grassland, 3 hectares of new plantation woodland and 3 hectares of natural grassland and scrub. -

Translating the Street

Translating the street Translating the street Brigitte Jurack Alan Dunn Chris Dobrowolski & Kitstop Models & Hobbies Kwong Lee & Birkenhead Central Library Casey Orr & The Hive, Wirral Youth Zone Alternator Studio & Project Space and Oxton Road, 13 April 2019 The work shown in this publication has been produced in three artist micro-residencies during which the artists spent time with businesses and community facilities in the vicinity of Alternator Studio & Project Space. Founded by Brigitte Jurack and Alan Dunn in 2012, Alternator is located in The Old Bakery at 57-59 Balls Road East, Birkenhead CH43 2TZ and leases spaces to artists. It has an additional outdoor building awaiting upgrading and the wider plan is for a dedicated space that is available all year round for micro-residencies for local and international artists, especially those seeking a large making-space close to the docklands and a multicultural neighbourhood. Alternator sees a future for the Translating the street project model using the Oxton Road neighbourhood as the key loca- tion for further micro-residencies. Front cover: location shoot for Casey Orr Our Birkenhead; Portraits with The Hive. Back cover: still from Kwong Lee Grzegorz’s Zurek. Illustration on p6: The Old Bakery circa 1905. The residencies and this publication have been suported by: INTRODUCTION is once again used to transform the small into Brigitte Jurack the substantial. International artists have been invited to translate the stories of the street, build In 2012 I took over one of the three remaining bridges and make visible the hitherto hidden. buildings on Balls Road East in Birkenhead. -

Pick-Me-Up, Your Handy Guide

Your local, independent charity Registered charity number 1034510 2 Our services I’m Jamie Anderson, Chief Executive of Age UK Wirral. I hope you find this Guide a handy and easy introduction to our services available throughout Wirral. Below I have set out the services we provide and on Page 6 under How to Use This Guide it tells you how you can access them where you live. Our services include: Health & Activity If you’re looking to get in shape, pick up a new pastime or Jamie Anderson simply get out of the house to meet new people then our CEO Health and Activity programme has something for you. With our range of activities you can exercise both mind & body. Opportunities include tai chi, seated exercise classes, yoga groups, arts and crafts, flower arranging, pilates and zumba gold and much more including a range of computer & technology courses for the beginner and all levels of ability; these embrace laptops, desktops, tablets, ipads and mobile phones. There are ‘One to One’ sessions were you can learn at your own pace too; it will take you on a journey of education, enlightenment, plus the fun and joys of digital technology We are based in our Activity Hub at Meadowcroft, Bromborough and also offer a range of outreach services and activities at various community centres and housing complexes across Wirral. Lunch & Coffee Corners These are held at multiple venues throughout the Wirral. You will have the opportunity to join other people in your area for an enjoyable meal or cup of coffee in lovely, friendly surroundings, with a varied selection of menu Pick-me-up Handy Guide 3 Home & Communities Service Sometimes we do not always have the friends, family or help around us that we need to stay safe and independent in our home. -

Liverpool the Mersey Ferry

AimAim • To learn about the River Mersey. SuccessSuccess Criteria • StatementI can locate 1 the Lorem River ipsum Mersey dolor on sita map amet of, consecteturthe UK. adipiscing elit. • StatementI can describe 2 the route of the River Mersey. • I can• Subgive statement information about places along the route. • I can give examples of different recreational activities which take place along the route. River Mersey Facts The River Mersey is 112km long (70 miles). Mersey means ‘boundary river’ in Anglo-Saxon. For centuries, the river formed part of the boundary between Lancashire and Cheshire. Many British Hindus consider the river to be sacred. Photo courtesy of ([email protected]) - granted under creative commons licence – attribution Where Is the River Mersey? The Course of the River Mersey The river is formed from three tributaries: the River Etherow (a tributary of the River Goyt), the River Goyt and the River Tame, which flows through Greater Manchester. The river starts at the confluence of the River Tame and River Goyt in Stockport, flowing through south Manchester, between Urmston and Sale, towards Warrington. Here it widens, before narrowing, as it passes by Runcorn and Widnes. From Runcorn, the river widens into a large estuary near Ellesmere Port. The Mersey finishes at Liverpool Bay, flowing into the Irish Sea. The Course Photo courtesy of ([email protected]) - granted under creative commons licence – attribution Stockport The River Goyt, which begins as a trickle high up in the Derbyshire hills, and the River Tame, which begins in Denshaw, Greater Manchester, merge together in Stockport to form the River Mersey. -

Indices of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) for Wirral 2015

Indices of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) for Wirral 2015 Produced by Wirral Council Public Health Intelligence Team November 2015 Indices of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) for Wirral 2015 By Sarah Kinsella, Senior Public Health Information Analyst, Wirral Council Business and Public Health Intelligence Team, Old Market House, Hamilton Street, Birkenhead, Wirral CH41 5AL 0151 666 5145 [email protected] Current Version: 3 Version Date Author Reviewer Actions History 0.1, 0.2 10/11/2015 Sarah Kinsella John Highton Reversed one map, Hannah typos & other minor Cotgrave amends. Report Overview Abstract Report explaining the measurement and distribution of deprivation in Wirral according to the latest Indices of Multiple Deprivation (2015) Intended or potential External audience Community & voluntary sector organisations, particularly those working in areas of deprivation Councillors and Constituency Managers NHS colleagues (e.g CCG, CT etc…) Internal JSNA Bulletin DMT (plus other departmental DMTs) Wider Public Health team Relevant LA Heads of Service Links with other topic areas This topic links with all topics where targeting of services based on deprivation or inequalities is customary Produced by Sarah Kinsella, NHS Wirral Performance & Public Health Intelligence Team October 2012 | Page 1 of 21 Contents Page Introduction 2 National & regional summary 4 Wirral summary 4 The seven deprivation domains: 6 - Income 6 - Employment 7 - Health Deprivation & Disability 7 - Education, Skills & Training 8 - Barriers to Housing & Services 9 - Crime 10 - Living Environment 10 Notes & further reading 15 Appendix 16 Introduction The Indices of Deprivation (also known as the Index of Multiple Deprivation or IMD) is a measure of relative deprivation at a small area level covering all 32,844 Lower Super Output Areas (LSOAs) in England. -

Information for Teachers and Group Leaders

Information for Teachers and Group Leaders Planning your visit to Birkenhead Priory Birkenhead The small place with a big history Priory www.thebirkenheadpriory.org Planning your visit Information for Teachers and Group Leaders Location of Birkenhead Priory Priory Street, Birkenhead, Wirral, CH41 5JH Open Wednesday to Sunday LIVERPOOL M62 Woodside James St. Bus Station Hamilton Sq. Hamilton Sq. BIRKENHEAD 3 Birkenhead Priory MARKET ST . A561 A41 .CHUR A41 IVY ST M53 PRIORY ST CH ST . 5 Birkenhead Priory Background to Birkenhead Priory The Birkenhead Priory, founded Far from being an isolated place of c1150, by the Benedictine monks is retreat, the priory monks looked after the oldest standing building on travellers for nearly 400 years and Merseyside and is a scheduled supervised the rst regulated "ferry ancient monument. Today it is across the Mersey", up to the Dissolution surrounded by modern Birkenhead, in 1536. First restored over a century factory units and is direct neighbour to ago, the site continues to develop and The camel Laird Shipyards. The whole share its rich history with recent history of the town is wrapped up in restoration and conservation. this one site – "the small place with a big history". There are a number of areas of interest on site, including The Chapter House, Undercroft, Refectory, Western Range, Scriptorium and St Mary's Tower, all of which create a great opportunity for exploring local history/geography units of work and enhancing cross curricular teaching and learning. Further detailed information on the site can be found on the website www.thebirkenheadpriory.org Birkenhead The small place with a big history 1 Priory www.thebirkenheadpriory.org Planning your visit Information for Teachers and Group Leaders What to see at Birkenhead Priory Chapter House (c1150) St Mary's Tower is the oldest building on site, is Designed by Thomas Rickman and consecrated as an Anglican church and completed in 1821, St Mary's Church is now home to the parish of St Mary's was built alongside the Priory ruins and Church and Christ the King. -

Ferries to the Rescue

Ferries to the Rescue Mike Royden (A chapter originally researched and written for Merseyside at War 1939-45, but edited out by the author, as the main focus was on the Home Front, although parts regarding service on the Mersey were retained within the chapter on ‘Defence of the Port’.) Mersey Ferries The Mersey Ferries played an important role in the defence of the port of Liverpool during the Second World War, and also carried out vital war work elsewhere. The Manx ferries too, a familiar site on the river, played an indispensable role, working in many supporting roles for the military and serving with great distinction and honour during the evacuation of Dunkirk. Although the Queensway Mersey Tunnel had opened in 1936, the Mersey Ferries were still essential to both commuters and pleasure seekers alike. Nevertheless, contingency plans for the safe operation of the Mersey ferries had been put in place a full year before outbreak of war. On 24 September 1938, meetings took place at the Mersey Docks & Harbour Building, where it was agreed that there should be no public lighting on the St George’s stage, nor the Wirral stages, while the ferries would only show navigation lights to the exterior at night and inside ‘if lights were necessary in the various rooms on such ferry boats, it would be necessary for all windows to be darkened and possibly for the lighting to be reduced in power’. In the event of an air raid when the ferry was crossing, ‘Such ferry should immediately come to rest and either stem the tide or anchor, and extinguish all lights’.