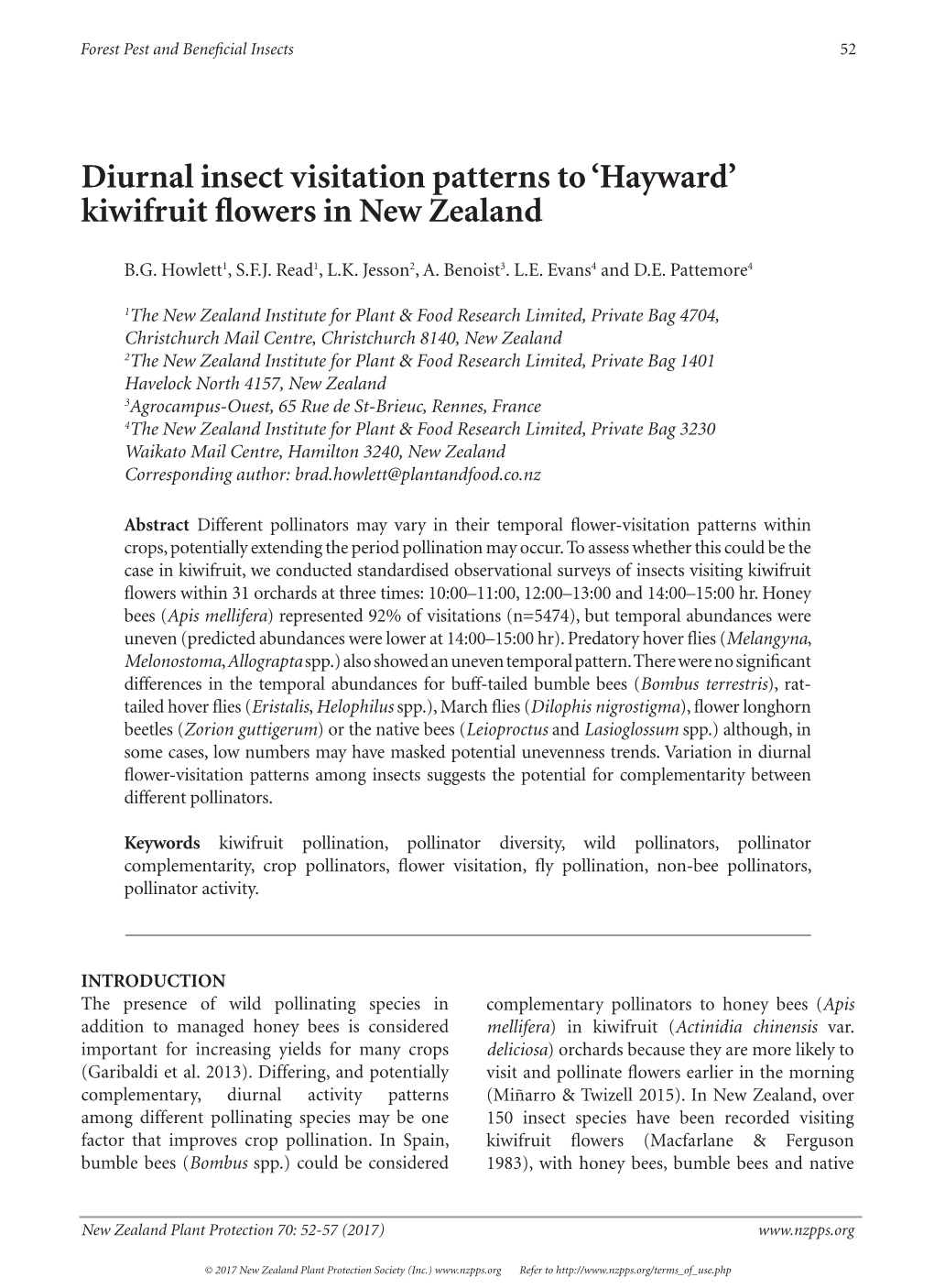

Diurnal Insect Visitation Patterns to 'Hayward' Kiwifruit Flowers in New

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apoidea (Insecta: Hymenoptera). Fauna of New Zealand 57, 295 Pp. Donovan, B. J. 2007

Donovan, B. J. 2007: Apoidea (Insecta: Hymenoptera). Fauna of New Zealand 57, 295 pp. EDITORIAL BOARD REPRESENTATIVES OF L ANDCARE R ESEARCH Dr D. Choquenot Landcare Research Private Bag 92170, Auckland, New Zealand Dr R. J. B. Hoare Landcare Research Private Bag 92170, Auckland, New Zealand REPRESENTATIVE OF UNIVERSITIES Dr R.M. Emberson c/- Bio-Protection and Ecology Division P.O. Box 84, Lincoln University, New Zealand REPRESENTATIVE OF M USEUMS Mr R.L. Palma Natural Environment Department Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa P.O. Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand REPRESENTATIVE OF OVERSEAS I NSTITUTIONS Dr M. J. Fletcher Director of the Collections NSW Agricultural Scientific Collections Unit Forest Road, Orange NSW 2800, Australia * * * SERIES EDITOR Dr T. K. Crosby Landcare Research Private Bag 92170, Auckland, New Zealand Fauna of New Zealand Ko te Aitanga Pepeke o Aotearoa Number / Nama 57 Apoidea (Insecta: Hymenoptera) B. J. Donovan Donovan Scientific Insect Research, Canterbury Agriculture and Science Centre, Lincoln, New Zealand [email protected] Manaaki W h e n u a P R E S S Lincoln, Canterbury, New Zealand 2007 4 Donovan (2007): Apoidea (Insecta: Hymenoptera) Copyright © Landcare Research New Zealand Ltd 2007 No part of this work covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means (graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping information retrieval systems, or otherwise) without the written permission of the publisher. Cataloguing in publication Donovan, B. J. (Barry James), 1941– Apoidea (Insecta: Hymenoptera) / B. J. Donovan – Lincoln, N.Z. : Manaaki Whenua Press, Landcare Research, 2007. (Fauna of New Zealand, ISSN 0111–5383 ; no. -

Pollination in New Zealand

2.11 POLLINATION IN NEW ZEALAND POLLINATION IN NEW ZEALAND Linda E. Newstrom-Lloyd Landcare Research, PO Box 69040, Lincoln 7640, New Zealand ABSTRACT: Pollination by animals is a crucial ecosystem service. It underpins New Zealand’s agriculture-dependent economy yet has hitherto received little attention from a commercial perspective except where pollination clearly limits crop yield. In part this has been because background pollination by feral honey bees (Apis mellifera) and other unmanaged non-Apis pollinators has been adequate. However, as pollinators decline throughout the world, the consequences for food production and national economies have led to increasing research on how to prevent further declines and restore pollination services. In New Zealand, managed honey bees are the most important pollinators of most commercial crops including pasture legumes, but introduced bumble bees can be more important in some crops and are increasingly being used as managed colonies. In addition, New Zealand has several other introduced bees and a range of solitary native bees, some of which offer prospects for development as managed colonies. Diverse other insects and some vertebrates also contribute to background pollination in both natural and agricultural ecosystems. However, New Zealand’s depend- ence on managed honey bees makes it vulnerable to four major threats facing these bees: diseases, pesticides, a limited genetic base for breeding varroa-resistant bees, and declining fl oral resources. To address the fourth threat, a preliminary list of bee forage plants has been developed and published online. This lists species suitable for planting to provide abundant nectar and high-quality pollen during critical seasons. -

Pheromone Trap Colour Determines Catch of Non-Target Insects

Horticultural Insects 216 PHEROMONE TRAP COLOUR DETERMINES CATCH OF NON-TARGET INSECTS G. CLARE1 , D.M. SUCKLING2,6, S.J. BRADLEY3, J.T.S WALKER3, P.W. SHAW4, J.M. DALY2, G.F. McLAREN5 and C.H. WEARING5 1HortResearch, Mt Albert Research Centre, PB 92169, Auckland 2HortResearch, Canterbury Research Centre, P.O. Box 51, Lincoln 3HortResearch, Hawke’s Bay Research Centre, Private Bag, Havelock North 4HortResearch, Nelson Research Centre, Private Bag, Riwaka 5HortResearch, Clyde Research Centre, RD 1, Alexandra 6Author for correspondence ABSTRACT Pheromone traps were operated in five regions to determine the impact of trap colour on catch of target and non-target insects. Red or green coloured pheromone sticky traps caught fewer native and introduced bees compared to the standard white traps, and yellow or blue traps. Honey bees (Apis mellifera) were caught mainly in white followed by blue traps, while bumble bees (Bombus spp.) were most attracted to blue traps, with most of the remainder caught in white traps. Native bee (Lasioglossum and Hylaeus spp.) catches were greatest in white traps, followed by yellow traps, with a few in green traps. There was no significant difference in catch of the target species, Cydia pomonella or Epiphyas postvittana, with trap colour. Replacement of the white traps with green or red traps is recommended to reduce non- target impacts on bees. Keywords: pheromone trapping, non-target, bees, codling moth, lightbrown apple moth. INTRODUCTION The New Zealand apple industry is reliant on export markets, which place phytosanitary restrictions on insects and their damage (Batchelor et al. 1997). Leafrollers and codling moth are key pests of apples and are the target of most insecticides in the crop. -

Biodiversity 13

FAR Foundation ForFOCUS Arable Research Issue 13, July 2018 FOCUS ISSUE Biodiversity 13 • What do we mean by “biodiversity” • Eco-system services and the benefits for arable farms • The benefits of biodiversity plantings on arable farms • Biodiversity and arable soils ® ADDING VALUE TO THE BUSINESS OF CROPPING © Foundation for Arable Research (FAR) DISCLAIMER This publication is copyright to the Foundation for Arable Research and may not be reproduced or copied in any form whatsoever without written permission. This FAR Focus is intended to provide accurate and adequate information relating to the subject matters contained in it. It has been prepared and made available to all persons and entities strictly on the basis that FAR, its researchers and authors are fully excluded from any liability for damages arising out of any reliance in part or in full upon any of the information for any purpose. No endorsement of named products is intended nor is any criticism of other alternative, but unnamed product. DISCLAIMER Unless agreed otherwise, the New Zealand Institute for Plant & Food Research Limited does not give any prediction, warranty or assurance in relation to the accuracy of or fitness for any particular use or application of, any information or scientific or other result contained in this FAR Focus. Neither Plant & Food Research nor any of its employees shall be liable for any cost (including legal costs), claim, liability, loss, damage, injury or the like, which may be suffered or incurred as a direct or indirect result of the reliance by any person on any information contained in this FAR Focus. -

Download Article As 860.87 KB PDF File

208 AvailableNew Zealandonline at: Journal http://www.newzealandecology.org/nzje/ of Ecology, Vol. 39, No. 2, 2015 Variable pollinator dependence of three Gastrodia species (Orchidaceae) in modified Canterbury landscapes Kristina J. Macdonald1, Zoë J. Lennon1, Lauretta L. Bensemann1, John Clemens2 and Dave Kelly1* 1School of Biological Sciences, University of Canterbury, Private Bag 4800, Christchurch 8140, New Zealand 2Christchurch Botanic Gardens, Christchurch City Council, PO Box 73036, Christchurch 8154, New Zealand *Author for correspondence (Email: [email protected]) Published online: 26 March 2015 Abstract: Pollination is an ecosystem service affected by anthropogenic activity, often resulting in reduced fruit set and increased extinction risk. Orchids worldwide have a wide range of pollination systems, but many New Zealand orchids are self-pollinating. We studied the pollination system of three saprophytic native orchids from the genus Gastrodia in modified landscapes in Canterbury, New Zealand: G. cunninghamii, G. minor, and an undescribed taxon G. “long column”. The species showed two distinct pollination systems. Gastrodia cunninghamii and G. minor were autonomous selfing species. In contrast, G. “long column” had almost no fruit set when pollinators were excluded, and was visited by the endemic New Zealand bee Lasioglossum sordidum, which acted as a pollen vector in order to produce fruit. Visitation rate by L. sordidum varied among four sites around Christchurch, and natural fruit set in G. “long column” ranged from 76% where L. sordidum were abundant to 10% where bees were not observed. Oddly, some of the highest natural fruit-set rates were at a highly modified urban site. Therefore, while some Gastrodia species are dependent on native pollinators, they can still persist in highly modified landscapes. -

Interactions Between Bee Species in Relation to Floral Resources

Interactions between bee species in relation to floral resources Jay Masao Iwasaki A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand January 2017 This thesis is dedicated to my father, Masataka Iwasaki For his patience, sacrifice, and support Abstract Bee communities in New Zealand are composed of native and introduced bees, including honey bees (Apis mellifera), which have been in the country for over 100 years. While there is evidence from other countries that honey bees compete with native bees, the interactions within New Zealand are not well understood. In addition, the arrival in New Zealand of the parasitic mite, Varroa destructor in 2000, and the subsequent loss of feral honey bees across the country has had unknown effects on the native pollinator community. How the loss of honey bees has affected other bee species can provide insight on the potential impact of honey bees prior to introduction to New Zealand and the potential impact prior to the introduction of varroa. To determine the impact of introduced bees on native bees, resource utilisation and overlap between bee species was estimated. The potential impact of honey bees on native bees was also examined with the addition of honey bee hives at a field site on The Remarkables mountain range, Otago, New Zealand. Lastly, the potential competitive impact of honey bees on bumblebees was examined experimentally in a glasshouse. Floral resources, composed of pollen and nectar, are the main food source for adult and larval bees. Different aspects of resource overlap can be compared to estimate the potential competition between bee species. -

Progress in Understanding Pollination Systems in New Zealand

New Zealand Journal of Botany ISSN: 0028-825X (Print) 1175-8643 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tnzb20 Progress in understanding pollination systems in New Zealand Linda Newstrom & Alastair Robertson To cite this article: Linda Newstrom & Alastair Robertson (2005) Progress in understanding pollination systems in New Zealand, New Zealand Journal of Botany, 43:1, 1-59, DOI: 10.1080/0028825X.2005.9512943 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/0028825X.2005.9512943 Published online: 17 Mar 2010. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 1454 View related articles Citing articles: 65 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tnzb20 New Zealand Journal of Botany, 2005, Vol. 43: 1-59 1 0028-825X/05/4301-0001 © The Royal Society of New Zealand 2005 Godley Review Progress in understanding pollination systems in New Zealand LINDA NEWSTROM Pollination systems in New Zealand have been Landcare Research characterised as unspecialised, imprecise entomoph- P.O. Box 69 ilous systems that correspond to the predominance Lincoln 8152, New Zealand of small white or pale flowers with dish or bowl ALASTAIR ROBERTSON shapes. We use a two-tiered conceptual framework Ecology Group incorporating a coarse-scale blossom class analysis Institute of Natural Resources and a finer scale syndrome concept analysis to as- Massey University sess the level of specialisation in plant-pollinator Private Bag 11222 relationships of New Zealand. Within each of the Palmerston North, New Zealand syndromes is a continuum of blossom classes: open-, directed-, and closed-access. -

Lincoln University Digital Dissertation

Lincoln University Digital Dissertation Copyright Statement The digital copy of this dissertation is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This dissertation may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: you will use the copy only for the purposes of research or private study you will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of the dissertation and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate you will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from the dissertation. Insect flower visitors in native plantings within the arable landscape of the Canterbury Plains A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Masters in Agricultural Science at Lincoln University by Franziska Gabriela Schmidlin Lincoln University 2018 Leiproctus fulvescens on Veronica salicifolia Abstract of a Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Masters in Agricultural Science. Abstract Insect flower visitors in native plantings within the arable landscape of the Canterbury Plains by Franziska Gabriela Schmidlin This thesis investigates the value of native plantings for pollination services within the arable landscape of Mid-Canterbury, New Zealand. The vegetation of the Canterbury Plains is among the most heavily modified landscapes in New Zealand with almost all original native vegetation replaced by intensive dairy and arable farming. Arable farmers often grow a variety of vegetable or herbage seed crops that depend on insect pollination. These include carrot, radish, onion, brassicas, and white and red clover. Intensive crop farming on the Canterbury Plains can therefore be highly dependent on a good provision of insect pollinators to maintain economically viable yields. -

Supplementary Figure 1 | an Overview of the Study Site Locations

Supplementary Figure 1 | An overview of the study site locations. Note that some of the symbols are overlapping where a study had temporal (yearly) replicates. Further details of studies are given in Supplementary Table 1. 1 0.5 1 0.4 0.8 0.3 0.6 0.2 0.4 flower visits 5 mostdominant 0.1 0.2 visits totalflower Mean contribution: 0.05 totalofproportionMean 0 0 0 5 10 15 20 25 ofproportionmeanCumulative Species abundance rank order Supplementary Figure 2 | The relationships between the species abundance rank order and the mean (cumulative) proportional contribution of species to the total crop- visitation by wild bee species. Depicted are means (±s.e. indicated by dashed lines) of 90 studies. 2 700 A 600 500 400 300 200 dominant species dominant unique of Number 100 0 0.00 0.05 0.10 0.15 0.20 Minimum contribution for species to qualify as dominant 25 B 20 15 10 5 species per study per species 0 Mean number of dominant dominant of number Mean 0.00 0.05 0.10 0.15 0.20 Minimum contribution for species to qualify as dominant 1 C 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0 visits by dominant species dominant by visits bee wild total of Proportion 0.00 0.05 0.10 0.15 0.20 Minimum contribution for species to qualify as dominant Supplementary Figure 3 | The relationship between threshold level for identifying dominant crop-visiting bee species and the proportion of the total wild bee visits made by dominant bee species. -

Hedging Our Bets: Choosing Hedgerow Plants to Enhance Beneficial

Hedging our bets: choosing hedgerow plants to enhance beneficial insects to optimise crop pollination and pest management on Canterbury farms Davidson MM, Howlett BG June 2010 A report prepared for: MAF SFF, Grant No. L09-009 Melanie M Davidson Plant & Food Research, Location Brad G Howlett Plant & Food Research, Location SPTS No. 4104 PFR Client Report No. 37105 PFR Contract No. 24631 DISCLAIMER Unless agreed otherwise, The New Zealand Institute for Plant & Food Research Limited does not give any prediction, warranty or assurance in relation to the accuracy of or fitness for any particular use or application of, any information or scientific or other result contained in this report. Neither Plant & Food Research nor any of its employees shall be liable for any cost (including legal costs), claim, liability, loss, damage, injury or the like, which may be suffered or incurred as a direct or indirect result of the reliance by any person on any information contained in this report. This report has been prepared by The New Zealand Institute for Plant & Food Research Limited (Plant & Food Research), which has its Head Office at 120 Mt Albert Rd, Mt Albert, Auckland. This report has been approved by: Melanie Davidson Scientist/Researcher, Vegetable, Arable & Southern Entomology Date: 23 June 2010 Louise Malone Science Group Leader, Applied Entomology Date: 23 June 2010 Contents Executive summary i 1 Introduction 3 2 Methods 4 3 Results 5 4 Conclusions and recommendations 9 5 Acknowledgements 10 6 References 10 7 Appendices 12 Executive summary Hedging our bets: choosing hedgerow plants to enhance beneficial insects to optimise crop pollination and pest management on Canterbury farms Davidson M, Howlett BG, June 2010, SPTS No. -

Conservation and Biology of the Rediscovered Nationally Endangered Canterbury Knobbled Weevil, Hadramphus Tuberculatus

ISSN: 1177-6242 (Print) ISSN: 1179-7738 (Online) ISBN: 978-0-86476-397-6 (Print) ISBN: 978-0-86476-398-3 (Online) Lincoln University Wildlife Management Report No. 57 Conservation and biology of the rediscovered nationally endangered Canterbury knobbled weevil, Hadramphus tuberculatus Jenifer Iles1, Mike Bowie1, Peter Johns2 & Warren Chinn3 1Department of Ecology, Lincoln University PO Box 85084, Lincoln 7647, Canterbury. 2Canterbury Museum, Rolleston Ave, Christchurch 8013, Canterbury. 3Department of Conservation, 70 Moorhouse Ave, Addington, Christchurch 8011. Prepared for: Department of Conservation 2007 (Summer Scholarship Report) 2015 (Published) 2 Abstract Three areas near Burkes Pass Scenic Reserve were surveyed for the presence of Hadramphus tuberculatus, a recently rediscovered endangered weevil. The reserve itself was resurveyed to expand on a 2005/2006 survey. Non-lethal pitfall traps and mark and recapture methods were used. Six H. tuberculatus were caught in pitfall traps over 800 trap nights. Day and night searching of Aciphylla aurea was conducted. Four specimens were observed on Aciphylla flowers between 9 am and 1.30 pm within the reserve. No specimens were found outside of the reserve by either method. Other possible locations where H. tuberculatus may be found were identified and some visited. At most locations Aciphylla had already finished flowering, no H. tuberculatus were found. Presence of H. tuberculatus at other sites would be best determined by searching of Aciphylla flowers during the morning from late October onwards. 3 Introduction Hadramphus tuberculatus belongs to a small genus of large, nocturnal flightless weevils (Craw 1999). The protected fauna list in the Seventh Schedule of the Wildlife Amendment Act 1980, included Hadramphus tuberculatus (Craw 1999) and it was identified as one of the highest priorities for conservation action in Canterbury by Pawson and Emberson (2000). -

Ecology of Native Bees in North Taranaki, New Zealand

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Ecology of Native Bees in North Taranaki, New Zealand A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Zoology at Massey University, Manawatū, New Zealand. Nikki Maria Hartley 2018 ii Abstract Studies are increasingly finding that native bees are important pollinators in many systems, in both natural and agricultural settings. With the possible loss of honey bees due to various reasons, it has become clear that relying on major pollinator for the world’s pollination needs is problematic. Instead, we must look to native, wild pollinators, such as solitary bees, to avoid declines in pollination rates. However, these native bees are at risk from a number of different factors worldwide including habitat destruction and degradation for agriculture, climate change, and pesticide use. It is therefore important to have a clear idea of the state of native pollinators, to assess how they are affected by these risks. This thesis gives a novel insight into the abundance and diversity of native bee species in the northern Taranaki area, New Zealand. I examined three main research questions concerning potential threats to native bees: how native bees are affected by varying land uses; how the abundances of native bees respond to different weather variables; and what the floral preferences of native bees in this region are.