Other “L” Marks

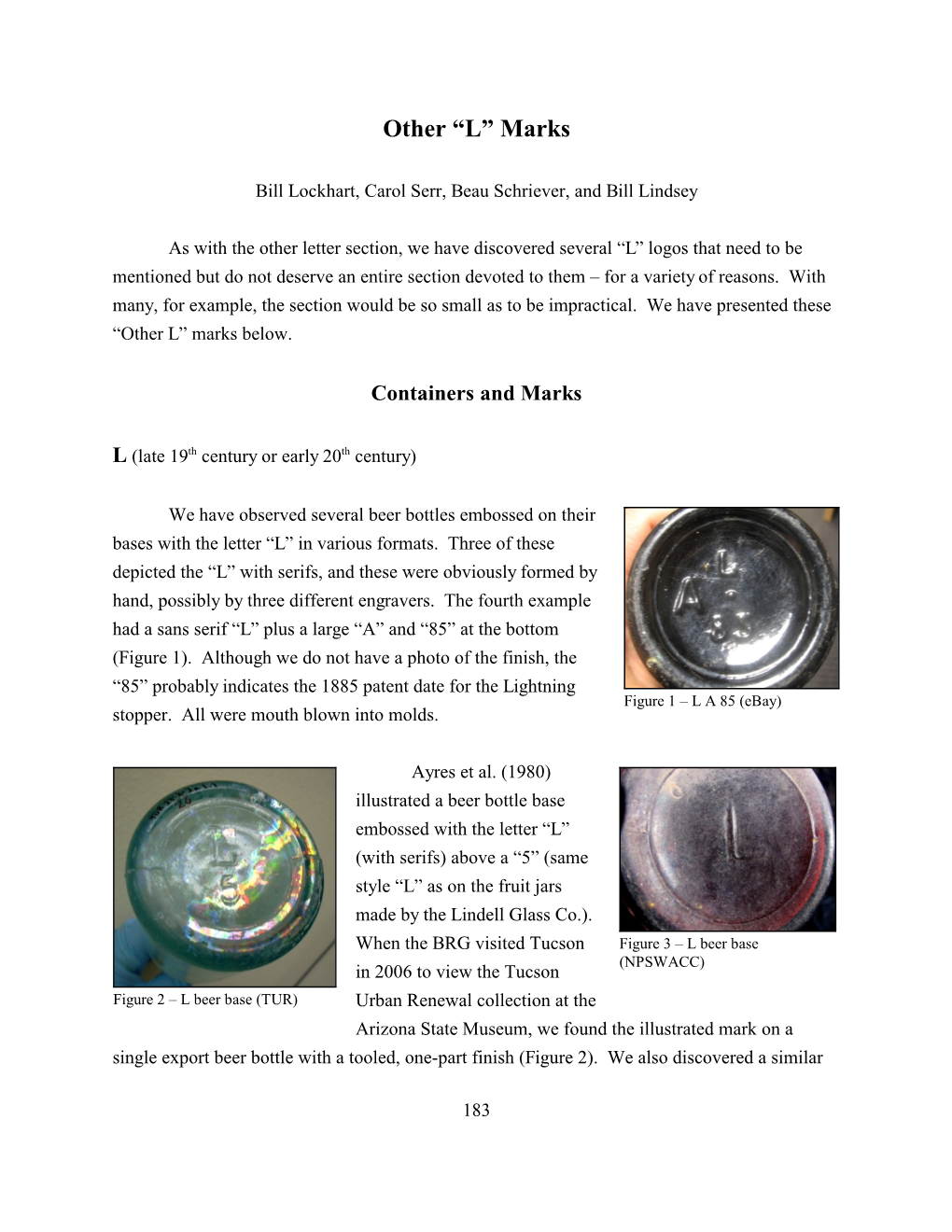

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Example of Closure Systems for Bottled Wine

Sustainability 2012, 4, 2673-2706; doi:10.3390/su4102673 OPEN ACCESS sustainability ISSN 2071-1050 www.mdpi.com/journal/sustainability Article The Importance of Considering Product Loss Rates in Life Cycle Assessment: The Example of Closure Systems for Bottled Wine Anna Kounina 1,2,*, Elisa Tatti 1, Sebastien Humbert 1, Richard Pfister 3, Amanda Pike 4, Jean-François Ménard 5, Yves Loerincik 1 and Olivier Jolliet 1 1 Quantis, Parc Scientifique EPFL, Bâtiment D, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland; E-Mails: [email protected] (E.T.); [email protected] (S.H.); [email protected] (Y.L.); [email protected] (O.J.) 2 Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL), 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland 3 Praxis Energia, rue Verte, 1261 Le Vaud, Switzerland; E-Mail: [email protected] 4 Quantis, 283 Franklin St. Floor 2, Boston, MA 02110, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 5 Quantis, 395 rue Laurier Ouest, Montréal, Québec, H2V 2K3, Canada; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +41-21-693-91-95; Fax: +41-21-693-91-96. Received: 23 July 2012; in revised form: 21 September 2012 / Accepted: 2 October 2012 / Published: 18 October 2012 Abstract: Purpose: The objective of this study is to discuss the implications of product loss rates in terms of the environmental performance of bottled wine. Wine loss refers to loss occurring when the consumer does not consume the wine contained in the bottle and disposes of it because of taste alteration, which is caused by inadequate product protection rendering the wine unpalatable to a knowledgeable consumer. -

Glass Container Styles

Glass Container Styles Glass Bottles & Jars Boston Round Bottles Boston Round Bottles are general use bottles that are perfect for liquids, product storage, and field or plant sampling projects. They feature a round body, rounded shoulders and narrow screw neck opening. These environmentally sensitive bottles help eliminate waste and help to ensure product integrity for long term storage. Clear / Flint Boston Round Bottles offers maximum visibility and sample integrity. Amber & Cobalt Blue Boston Round Bottles protect contents from UV rays and are ideal for light sensitive products. Composite Test Jars Clear / Flint Composite Test Jars are clear wide-mouth straight sided jars that are ideal for sampling and provide maximum content visibility. These bottles are designed without shoulders for maximum storage capacity. French Square Bottles Clear / Flint French Square Bottles provide maximum content visibility. The space saving design saves on shelf and storage space. The wide mouth opening is ideal for mixing, storing and sampling. Graduated Medium Round Bottles Bottle Beakers® also known as Graduated Medium Rounds are excellent for use with biological and pathological specimens, but can also be used for storing industrial laboratory chemicals and reagents. These clear / flint bottles are designed with a slight shoulder for easy pouring and handling. Graduated in ml and ounces. Mix, measure, and store in the same container. Media Bottles Media Bottles are manufactured from PYREX® borosilicate glass for chemical and thermal resistance and can be used for storage as well as mixing and sampling. Regular Media Bottles have permanent white enamel graduations and marking spots. PYREXPlus® Media Bottles have a protective PVC coating helps prevent glass from shattering and reduces spills. -

Laboratory Supplies and Equipment

Laboratory Supplies and Equipment Beakers: 9 - 12 • Beakers with Handles • Printed Square Ratio Beakers • Griffin Style Molded Beakers • Tapered PP, PMP & PTFE Beakers • Heatable PTFE Beakers Bottles: 17 - 32 • Plastic Laboratory Bottles • Rectangular & Square Bottles Heatable PTFE Beakers Page 12 • Tamper Evident Plastic Bottles • Concertina Collapsible Bottle • Plastic Dispensing Bottles NEW Straight-Side Containers • Plastic Wash Bottles PETE with White PP Closures • PTFE Bottle Pourers Page 39 Containers: 38 - 42 • Screw Cap Plastic Jars & Containers • Snap Cap Plastic Jars & Containers • Hinged Lid Plastic Containers • Dispensing Plastic Containers • Graduated Plastic Containers • Disposable Plastic Containers Cylinders: 45 - 48 • Clear Plastic Cylinder, PMP • Translucent Plastic Cylinder, PP • Short Form Plastic Cylinder, PP • Four Liter Plastic Cylinder, PP NEW Polycarbonate Graduated Bottles with PP Closures Page 21 • Certified Plastic Cylinder, PMP • Hydrometer Jar, PP • Conical Shape Plastic Cylinder, PP Disposal Boxes: 54 - 55 • Bio-bin Waste Disposal Containers • Glass Disposal Boxes • Burn-upTM Bins • Plastic Recycling Boxes • Non-Hazardous Disposal Boxes Printed Cylinders Page 47 Drying Racks: 55 - 56 • Kartell Plastic Drying Rack, High Impact PS • Dynalon Mega-Peg Plastic Drying Rack • Azlon Epoxy Coated Drying Rack • Plastic Draining Baskets • Custom Size Drying Racks Available Burn-upTM Bins Page 54 Dynalon® Labware Table of Contents and Introduction ® Dynalon Labware, a leading wholesaler of plastic lab supplies throughout -

Glass Teacher Book 20

Exploring the Glass City: Toledo Museum of Art A Teacher’s Guide to the Glass Pavilion P.O. Box 1013 Toledo, Ohio 43697-1013 Hours Tuesday-Saturday 10A.M. - 4P.M. Friday 10A.M. - 10P.M. Sunday 11A.M. - 5P.M. Closed Monday Admission Free to all thanks in part to the support of Museum members. There is a charge for select ticketed exhibitions. Directions Just off I-75 near Downtown Toledo Take either the Collingwood or Detroit Avenue exits, then follow the signs. Information 419.255.8000 www.toledomuseum.org Our Mission We believe in the power of art to ignite the imagination, stimulate thought, and provide enjoyment. Through our collection and programs, we strive to integrate art into the lives of people. 1 Welcome to the Glass Pavilion Exploring the Glass City: Talkin’ Glass...Words to Know A Teacher’s Guide to the Glass Pavilion What Is Glass, Anyway? Fuse(ing) heating cut glass in a kiln to melt pieces together. The activities in this guide are designed to be used prior to Glass is the oldest man-made material. Most glass is a mixture your visit to enhance learning that will take place at the of silica (from sand or sandstone), an alkali to lower the melting Furnace Museum, or after you return to the classroom. Each activity point, and lime to act as a stabilizer. The mixture, when an enclosed structure for the production and application of is aligned to the Ohio Academic Content Standards. melted, fuses together. It can be poured or blown into a shape heat. -

Carbopol Pemulen Or Noveon Loss on Drying Test Procedure

LUBRIZOL TEST PROCEDURE Test Procedure SA-004 Edition: August, 2010 Loss on Drying Applicable Products: Carbopol®* Polymers, Pemulen™* Polymeric Emulsifiers and Noveon®* AA-1 Polycarbophil Scope: Apparatus: This procedure is for the determination of 1. Vacuum oven controlled at 80 ± 2°C (176 ± volatile materials in Carbopol® polymers, 4°F) with a vacuum of 29 inches (736 mm) Hg. ® Pemulen™ polymeric emulsifiers and Noveon 2. Vacuum oven controlled at 45 ± 2°C (113 ± AA-1 polycarbophil. 4°F) with a vacuum of 29 inches (736 mm) Hg. 3. Balance capable of ±0.0001 g accuracy. Abstract: 4. Heat safe weighing bottle with glass stopper. A weighed sample of polymer is placed in a 5. Desiccator with silica gel desiccant. vacuum oven at a vacuum of 29 inches (736 mm) 6. Vacuum pump. Hg at the specified temperature and time. The sample is cooled, reweighed and the percent weight loss calculated. Safety Precautions: 1. Wear safety goggles and gloves. 2. Polymer dust is irritating to the respiratory passages and inhalation should be avoided. 3. See all Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS) for additional safety and handling information. Interferences: Care must be taken to avoid moisture pick-up from the atmosphere. The most accurate measurements can be expected from samples removed the first time the sample container is opened. Because of the hygroscopic nature of Carbopol® polymers, Pemulen™ polymeric emulsifiers and Noveon® AA-1 polycarbophil, moisture pick-up each time the sample container is opened will influence the loss on drying. Lubrizol Advanced Materials, Inc. / 9911 Brecksville Road, Cleveland, Ohio 44141-3247 / TEL: 800.379.5389 or 216.447.5000 The information contained herein is believed to be equipment used commercially in processing these Materials, Inc.’s direct control. -

Bottlesinsmall Case for Unlimitedapplications

BOTTLES KIMAX® media bottles are the perfect bottle for any application. The outstanding quality ensures a wide range of use, from long term storage and transporting to the most demanding applications in the pharmaceutical and food industries. Sturdy design and improved clarity allow contents and volume to be checked quickly, while temperature resistance makes the bottles ideal for autoclaving. Essential to every laboratory, KIMAX® media bottles are proven reliable for unlimited applications. We offer a wide variety of general purpose bottles in small case quantities or large bulk packs with a variety of closures. We also offer containers with or without caps attached for high use items or facilities with centralized stockrooms. Customization to meet your specific needs is simpler than ever, including pre-cleaning and barcoding. Trust DWK Life Sciences to be the exclusive source for all your laboratory glass needs. DWK Life Sciences 22 BOTTLES Clear Glass Boston Round / Amber Glass Boston Round Clear Glass Boston Round Bottles Amber Glass Boston Round Bottles Kimble® Clear Boston Rounds are made from Type III Kimble® Amber Boston Rounds are made from Type III soda-lime glass and have a narrow-mouth design. Clear soda-lime glass and have a narrow-mouth design. Amber bottles allow for viewing of contents. They come with a bottles protect light-sensitive contents. They come with a variety of caps and liner combinations and are designed variety of caps and liner combinations. They are designed to protect the quality of liquids and product storage. to protect contents from UV rays and are ideal for light- sensitive products. -

BMW of North America, LLC NJ ""K"" Line America, Inc. VA 1199

The plan sponsors listed below have at least one application for the Retiree Drug Subsidy (RDS) program in an "Approved" status for a plan year ending in 2010 as of February 4, 2011. The state listed for each sponsor is the state provided by the sponsor on the application for the subsidy. This state may, or may not, be where the majority of the plan sponsor's retirees reside or where the plan sponsor is headquartered. This list will be updated periodically. Plan Plan Sponsor Business Name Sponsor State : BMW of North America, LLC NJ ""K"" Line America, Inc. VA 1199 SEIU Greater New York Benefit Fund NY 1199 SEIU National Benefit Fund NY 3M Company MN 4th District IBEW Health Fund WV A-C RETIREES' VOLUNTARY BENFITS PLAN WI A. DUDA & SONS, INC. FL A. SCHULMAN, INC OH A. T. Massey Coal Company, Inc. VA A&E Television Networks NY AAA EAST PENN PA AARP DC ABB Inc. CT Abbott Laboratories IL Abbott Pharmaceuticals PR Ltd. PR Acadia Parish School Board LA Accenture LLP IL Accuride Corporation IN ACF Industries LLC MO ACGME IL Acton Health Insurance Trust MA Actuant Corporation WI Adirondack Central School NY Administrative Office of the Pennsylvania Courts PA Adventist Risk Management MD Advisory Services OH AEGON USA, Inc. IA AFL-CIO Health and Welfare Trust DC AFSCME DC AFSCME Council 31 IL afscme d.c. 47 health & welfare fund PA AFSCME District Council 33 Health and Welfare Plan PA AFTRA Health Fund NY AGC FLAT GLASS NORTH AMERICA INC TN Page 1 AGC-IUOE Local 701 Health & Welfare Trust Fund WA AGCO Corporation GA Agilent Technologies, Inc. -

Jan. 3, 1967 H. C. A. EVERS ETAL 3,295,525 SELF-ASPIRATING CARTRIDGE AMPOULE Filed April 7, 1964

Jan. 3, 1967 H. C. A. EVERS ETAL 3,295,525 SELF-ASPIRATING CARTRIDGE AMPOULE Filed April 7, 1964 K. K. a/1a/yapas M24/VS 6as Zaat 176ao A227as sp12.1/ 12476a 2/774/// attazá3. 1772a Mays 3,295,525 United States Patent Office Patented Jan. 3, 1967 1. 2 the interior of the ampoule, includes the elastic mem 3,295,525 brane and is substantially plane. SELF-ASPERATING CARTRIDGE AMPOULE The reason why the bubble gets easily loose from the Hans Christer Arvid Evers and Sven Paul Littorin, Soder talje, Sweden, assignors to Aktiebolaget Astra, Apote plunger is probably that there is no narrow pocket in karnes Kemiska Fabriker, Sodertalje, Sweden, a com the plunger, and that bubbles are probably more inclined pany of Sweden to adhering to a rubber surface than to a glass surface. Filed Apr. 7, 1964, Ser. No. 358,034 As is well known bubbles have a tendency for gathering Claims priority, application Sweden, Apr. 9, 1963, in "concave corners.” In the known plunger there is a 3,975/63 concave corner defined by two rubber walls, whereas the 1 Claim. (C. 128-272) 10 plunger of the present invention has a concave corner defined by a rubber wall and a glass wall. This invention relates to a self-aspirating cartridge The invention will now be more fully disclosed with ampoule of the known type in which the aspiration is reference to the accompanying drawing which illustrates produced by a particular shape of the rubber stopper an embodiment of a cartridge ampoule of the invention. -

Glass and Glass-Ceramics

Chapter 3 Sintering and Microstructure of Ceramics 3.1. Sintering and microstructure of ceramics We saw in Chapter 1 that sintering is at the heart of ceramic processes. However, as sintering takes place only in the last of the three main stages of the process (powders o forming o heat treatments), one might be surprised to see that the place devoted to it in written works is much greater than that devoted to powder preparation and forming stages. This is perhaps because sintering involves scientific considerations more directly, whereas the other two stages often stress more technical observations M in the best possible meaning of the term, but with manufacturing secrets and industrial property aspects that are not compatible with the dissemination of knowledge. However, there is more: being the last of the three stages M even though it may be followed by various finishing treatments (rectification, decoration, deposit of surfacing coatings, etc.) M sintering often reveals defects caused during the preceding stages, which are generally optimized with respect to sintering, which perfects them M for example, the granularity of the powders directly impacts on the densification and grain growth, so therefore the success of the powder treatment is validated by the performances of the sintered part. Sintering allows the consolidation M the non-cohesive granular medium becomes a cohesive material M whilst organizing the microstructure (size and shape of the grains, rate and nature of the porosity, etc.). However, the microstructure determines to a large extent the performances of the material: all the more reason why sintering Chapter written by Philippe BOCH and Anne LERICHE. -

Basic Considerations for Container Closure Selection of Parenteral Drug Products Lakshmi Prasanna Kolluru*

A tica nal eu yt c ic a a m A r a c t h a P Kolluru, Pharm Anal Acta 2017, 8:5 Pharmaceutica Analytica Acta DOI: 10.4172/2153-2435.1000e189 ISSN: 2153-2435 Editorial Open Access Basic Considerations for Container Closure Selection of Parenteral Drug Products Lakshmi Prasanna Kolluru* Medefil Inc, Glendale Heights, IL 60139, USA. *Corresponding author: Lakshmi Prasanna Kolluru, Sr. Formulation Scientist, Medefil Inc., 250/405 Windy Point Drive, Glendale Heights, IL 60139, USA, Tel: +1-630-682-4600; Email: [email protected] Received date: May 02, 2017; Accepted date: May 10, 2017; Published date: May 16, 2017 Copyright: © 2017 Kolluru LP. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Editorial usage of RTU components can aid in reducing the risk on contamination of the drug product [4]. By definition, container closure system encompasses all components of the packaging system that hold and protect the drug product. It Intended use includes primary packaging system (components with which the drug product comes in direct contact) and secondary packaging system Container-closure selection varies for liquid and lyophilized drug (components that offer additional protection to the system but do not products. Traditionally, tubular vials are preferred over molded vials come in direct contact with the drug product). This article focuses on during lyophilization because of the flat bottom of vials that help in primary packaging components as they have a significant effect on the uniform heat transfer from the freeze drying shelves to the drug critical quality attributes of the drug product throughout the product product. -

Parts Catalog 10 03.P65

TupperwareItem # Mold # DescriptionParts Catalog Credit Value Suggested Retail Item # Mold # Description Credit Value Suggested Retail 2440 ................. 13 .................... Paddle Scraper/Spatula ...................................................... 0.49 .............................. 0.98 OBS ................. 39/40 ............... Soap Case .......................................................................... 0.35 OBS ................. 52/55 ............... Bye Fly Swatter ................................................................... 0.49 OBS ................. 61 .................... Curl Comb ........................................................................... 0.29 OBS ................. 62 .................... Purse Comb ........................................................................ 0.29 OBS ................. 63 .................... Pocket Comb ...................................................................... 0.46 OBS ................. 64 .................... Man’s Dresser Comb .......................................................... 0.55 OBS ................. 93 .................... Nursery Tray ....................................................................... 0.74 OBS ................. 101 .................. 2-oz. Midgets® cont. C.S. see # 4789 .............................. 1.07 OBS ................. 102 .................. Spice Shaker see #1843, #1844 ........................................ 0.73 OBS ................. 107 .................. 16-oz Tumbler see #3515 .................................................. -

INSTRUCTIONS for USE It

INSTRUCTIONS FOR USE it. Do not use it if the liquid is discolored or contains any lumps or large particles in it. STRENSIQ® [stren' sik] Throw it away and get a new (asfotase alfa) vial. injection, for subcutaneous use Step 2: Using your thumb, flip the vial plastic cap off the STRENSIQ vial. Read this “Instructions for Use” before you start using STRENSIQ and each time you get a refill. There may be new information. This information does not take the place of talking to your healthcare provider about your medical condition or your treatment. Step 3: Remove the larger bore Do not share your syringes or needles with anyone else. You may give an infection needle (e.g., 25 G) from the to them or get an infection from them. package. Pick up the syringe and place the needle on the Supplies needed to give your STRENSIQ injection (See Figure A): tip of the syringe. Push down • 1 or 2 STRENSIQ vial(s). and twist the needle onto • 1 or 2 sterile disposable 1 mL syringes for injection with 25 to 29 gauge (G), the syringe until it is tight. ½ inch needles. Step 4: Hold the syringe with the o The use of two different gauge needles is recommended, a larger needle pointing up and pull bore needle (e.g. 25 gauge) for withdrawal of the medication, and back the plunger until the a smaller bore needle (e.g. 29 gauge) for the injection. top of the plunger reaches o Always use a new syringe and needle for each injection.