Cesifo Working Paper No. 8217

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ist Cover Page-I-Ii.P65

DISTRICT HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT NORTH 24 PARGANAS DEVELOPMENT & PLANNING DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL District Human Development Report: North 24 Parganas © Development and Planning Department Government of West Bengal First Published February, 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission from the Publisher. Front Cover Photograph: Women of SGSY group at work. Back Cover Photograph: Royal Bengal Tiger of the Sunderban. Published by : HDRCC Development & Planning Department Government of West Bengal Setting and Design By: Saraswaty Press Ltd. (Government of West Bengal Enterprise) 11 B.T. Road, Kolkata 700056 Printed by: Saraswaty Press Ltd. (Government of West Bengal Enterprise) 11 B.T. Road, Kolkata 700056 While every care has been taken to reproduce the accurate date, oversights/errors may occur. If found, please convey it to the Development and Planning Department, Government of West Bengal. Minister-in-Charge Department of Commerce & Industries, Industrial Reconstruction, Public Enterprises and Development & Planning GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL E-mail : [email protected] Foreword It has been generally accepted since ancient times that welfare and well being of human is the ultimate goal of Human Development. An environment has to be created so that the people, who are at the centre of the churning process, are able to lead healthy and creative lives. With the publication of the West Bengal Human Development Report in 2004 and it being subsequently awarded by the UNDP for its dispassionate quality of analysis and richness in contents, we had to strive really hard to prepare the District Human Development Reports. -

Rainfall, North 24-Parganas

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN 2016 - 17 NORTHNORTH 2424 PARGANASPARGANAS,, BARASATBARASAT MAP OF NORTH 24 PARGANAS DISTRICT DISASTER VULNERABILITY MAPS PUBLISHED BY GOVERNMENT OF INDIA SHOWING VULNERABILITY OF NORTH 24 PGS. DISTRICT TO NATURAL DISASTERS CONTENTS Sl. No. Subject Page No. 1. Foreword 2. Introduction & Objectives 3. District Profile 4. Disaster History of the District 5. Disaster vulnerability of the District 6. Why Disaster Management Plan 7. Control Room 8. Early Warnings 9. Rainfall 10. Communication Plan 11. Communication Plan at G.P. Level 12. Awareness 13. Mock Drill 14. Relief Godown 15. Flood Shelter 16. List of Flood Shelter 17. Cyclone Shelter (MPCS) 18. List of Helipad 19. List of Divers 20. List of Ambulance 21. List of Mechanized Boat 22. List of Saw Mill 23. Disaster Event-2015 24. Disaster Management Plan-Health Dept. 25. Disaster Management Plan-Food & Supply 26. Disaster Management Plan-ARD 27. Disaster Management Plan-Agriculture 28. Disaster Management Plan-Horticulture 29. Disaster Management Plan-PHE 30. Disaster Management Plan-Fisheries 31. Disaster Management Plan-Forest 32. Disaster Management Plan-W.B.S.E.D.C.L 33. Disaster Management Plan-Bidyadhari Drainage 34. Disaster Management Plan-Basirhat Irrigation FOREWORD The district, North 24-parganas, has been divided geographically into three parts, e.g. (a) vast reverine belt in the Southern part of Basirhat Sub-Divn. (Sundarban area), (b) the industrial belt of Barrackpore Sub-Division and (c) vast cultivating plain land in the Bongaon Sub-division and adjoining part of Barrackpore, Barasat & Northern part of Basirhat Sub-Divisions The drainage capabilities of the canals, rivers etc. -

Selecting the Best of Us? Politician Quality in Village Councils in West Bengal, India

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Chaudhuri, Ananish; Iversen, Vegard; Jensenius, Francesca R.; Maitra, Pushkar Working Paper Selecting the Best of Us? Politician Quality in Village Councils in West Bengal, India CESifo Working Paper, No. 8597 Provided in Cooperation with: Ifo Institute – Leibniz Institute for Economic Research at the University of Munich Suggested Citation: Chaudhuri, Ananish; Iversen, Vegard; Jensenius, Francesca R.; Maitra, Pushkar (2020) : Selecting the Best of Us? Politician Quality in Village Councils in West Bengal, India, CESifo Working Paper, No. 8597, Center for Economic Studies and Ifo Institute (CESifo), Munich This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/226299 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

Hingalganj Assembly West Bengal Factbook

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : www.electionsinindia.com Online Book Store : www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Report No. : AFB/WB-126-0619 ISBN : 978-93-5293-668-7 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : June, 2019 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 167 for the use of this publication. Printed in India No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency at a Glance | Features of Assembly as per 1-2 Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps 2 Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency in District | Boundaries 3-9 of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary Constituency | Town & Village-wise Winner Parties- 2019, 2016, 2014, 2011 and 2009 Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 10-14 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographics 4 Population | Households | Rural/Urban Population | Towns and Villages by 15-16 Population Size | Sex Ratio (Total -

E2767 V. 2 Public Disclosure Authorized ACCELERATED DEVELOPMENT of MINOR IRRIGATION (A.D.M.I) PROJECT in WEST BENGAL

E2767 v. 2 Public Disclosure Authorized ACCELERATED DEVELOPMENT OF MINOR IRRIGATION (A.D.M.I) PROJECT IN WEST BENGAL ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT Public Disclosure Authorized ANNEXURE (Part II) November 2010 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Annexure - I - Map of West Bengal showing Environmental Features Annexure – II - Sample Blocks Annexure – III - Map of West Bengal Soils Annexure – IV - Ground Water Availability in Pilot Districts Annexure – V - Ground Water Availability in non-pilot districts Annexure – VI - Arsenic Contamination Maps of Districts Annexure – VII - Details of Wetlands more than 10 ha Annexure – VIII - Environmental Codes of Practice Annexure – IX - Terms of Reference for Limited EA Annexure – X - Environmental Survey Report of Sample Blocks Annexure – XI - Stakeholder Consultation Annexure – XII - Primary & Secondary Water Quality Data Annexure – XIII - Primary & Secondary Soil Quality Data Annexure – XIV - EMP Master Table ii Annexure II Sample Blocks for Environmental Assessment Agro- Hydrogeological No. of climatic Soil group District Block Status of the Block Samples zone Hill Zone Acid soils/sandy Jalpaiguri Mal Piedmont zone 1 loam Terai Acid soils/sandy Darjeeling Phansidewa Piedmont zone 1 Teesta loam Flood plain Acid soils/sandy Jalpaiguri Dhupguri Recent to sub-recent 1 loam alluvium Acid soils/sandy Coochbehar Tufangunge II Recent to sub-recent 1 loam alluvium Acid soils/sandy Coochbehar Sitai Recent to subrecent 1 loam alluvium Vindhyan Alluvial/sandy Dakshin Gangarampur( Older alluvium -

Climate Change, Migration and Adaptation in Deltas: Key Findings

CLIMATE CHANGE, MIGRATION AND ADAPTATION IN DELTAS Key findings from the DECCMA project BANGLADESH UNIVERSITY JADAVPUR UNIVERSITY OF GHANA OF ENGINEERING & UNIVERSITY INDIA TECHNOLOGY CONTENTS Our approach and research activities 1 Why are deltas important? 6 What we have done 8 What we have done: economic modelling 10 What we have done: integrated assessment modelling 12 Present situation in deltas 14 At risk from climate change – sea level rise, coastal erosion, flooding, salinization 16 Deltas play a key role in national economies 18 Migration from rural areas to nearby urban areas is a continuing trend, driven largely by economic opportunity 20 Migration has consequences in both sending and receiving areas 22 Environment is a proximate cause of migration 23 Displacement and planned relocation 24 Adaptation is occurring now 30 Livelihood adaptations 31 Structural adaptations 33 Migration as an adaptation 34 Sub-optimal policy and implementation framework for migration and adaptation 36 Future situation in deltas 38 Impacts of 1.5OC temperature increase 40 Climate change will lead to significant economic losses by 2050 42 More adaptation will be needed 44 Modelling what determines adaptation decisions 46 Influential drivers of adaptation decisions by male- and female-headed households 47 Engagement and impact 50 Raising the profile of delta residents with parliamentarians (Volta) 52 Inputs to the Coastal Development Authority Bill (Volta) 53 Requested to provide inputs to policy and highlighting delta migration (Mahanadi) 54 Partnership with the West Bengal State Department of Environment (Indian Bengal delta) 55 Capacity building 56 Outputs 63 DECCMA team members 72 OUR APPROACH OUR APPROACH AND RESEARCH ACTIVITIES 4 5 1. -

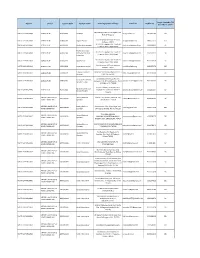

COVID Session Sites North 24 Parganas 10.3.21

COVID Session Sites North 24 Parganas 10.3.21 Sl No District /Block/ ULB/ Hospital Session Site name Address Functional Status Ashoknagar Kalyangarh 1 Ashoknagar SGH Govt. Functional Municipality 2 Bangaon Municipality Bongaon SDH & SSH Govt. Functional 3 Baranagar Municipality Baranagar SGH Govt. Functional 4 Barasat Municipality Barasat DH Govt. Functional 5 Barrackpur - I Barrackpore SDH Govt. Functional 6 Bhatpara Municipality Bhatpara SGH Govt. Functional Bidhannagar Municipal 7 Salt Lake SDH Govt. Functional Corporation 8 Habra Municipality Habra SGH Govt. Functional 9 Kamarhati Municipality Session 1 Academic Building Govt. Functional Session 2 Academic Building, Sagar Dutta Medical college 10 Kamarhati Municipality Govt. Functional and hospital 11 Kamarhati Municipality Session 3 Lecture Theater Govt. Functional 12 Kamarhati Municipality Session 4 Physiology Dept Govt. Functional 13 Kamarhati Municipality Session 5 Central Library Govt. Functional 14 Kamarhati Municipality Collage of Medicine & Sagore Dutta MCH Govt. Functional 15 Khardaha Municipality Balaram SGH Govt. Functional 16 Naihati Municipality Naihati SGH Govt. Functional 17 Panihati Municipality Panihati SGH Govt. Functional 18 Amdanga Amdanga RH Govt. Functional 19 Bagda Bagdah RH Govt. Functional 20 Barasat - I Chhotojagulia BPHC Govt. Functional 21 Barasat - II Madhyamgram RH Govt. Functional 22 Barrackpur - I Nanna RH Govt. Functional 23 Barrackpur - II Bandipur BPHC Govt. Functional 24 Bongaon Sundarpur BPHC Govt. Functional 25 Deganga Biswanathpur RH Govt. Functional 26 Gaighata Chandpara RH Govt. Functional 27 Habra - I Maslandpur RH Govt. Functional 28 Habra - II Sabdalpur RH Govt. Functional 29 Rajarhat Rekjoani RH Govt. Functional 30 Amdanga Adhata PHC Govt. Functional 31 Amdanga Beraberia PHC Govt. Functional 32 Amdanga Maricha PHC Govt. Functional 33 Bagda Koniara PHC Govt. -

Kolkata 700 017 Ph

WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTION COMMISSION 18, Sarojini Naidu Sarani (Rawdon Street) – Kolkata 700 017 Ph. No. 2280-5805; FAX- 2280-7373 No. 1820-SEC/1D-134/2012 Kolkata, the 3rd December, 2012 O R D E R In exercise of the power conferred by Sections 16 and 17 of the West Bengal Panchayat Elections Act, 2003 (West Bengal Act XXI of 2003), read with rules 26 and 27 of the West Bengal Panchayat Elections Rules, 2006, West Bengal State Election Commission, hereby publish the draft Order for delimitation of North 24 Parganas Zilla Parishad constituencies and reservation of seats thereto. The Block(s) have been specified in column (1) of the Schedule below (hereinafter referred to as the said Schedule), the number of members to be elected to the Zilla Parishad specified in the corresponding entries in column (2), to divide the area of the Block into constituencies specified in the corresponding entries in column (3),to determine the constituency or constituencies reserved for the Scheduled Tribes (ST), Scheduled Castes (SC) or the Backward Classes (BC) specified in the corresponding entries in column (4) and the constituency or constituencies reserved for women specified in the corresponding entries in column (5) of the said schedule. The draft will be taken up for consideration by the State Election Commissioner after fifteen days from this day and any objection or suggestion with respect thereto, which may be received by the Commission within the said period, shall be duly considered. THE SCHEDULE North 24 Parganas Zilla Parishad North 24 Parganas District Name of Number of Number, Name and area Constituenci- Constituen- Block members to of the Constituency es reserved cies be elected for ST/SC/ BC reserved for to the Zilla persons women Parishad (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) Bagdah 3 Bagdah/ ZP-1 SC Women Sindrani, Malipota and Kaniara-II grams. -

District Sector Course Code Course Name Training Center Address E-Mail ID Mobile No 31St March 2019

Target Available Till District Sector Course Code Course Name Training Center Address E-mail ID Mobile No 31st March 2019 Mama Bhagina Bus stand, Bagdah, Dist- NORTH 24 PARGANAS AGRICULTURE AGR/Q0801 Gardener [email protected] 9874062186 570 Norh 24 Parganas Prafulla Kanan, VIP Road, Kestopur, NORTH 24 PARGANAS AGRICULTURE AGR/Q1201 Organic Grower [email protected] 9830037376 254 Kolkata - 700101 Vill +PO+PS : Bagdah, Dist : North 24 NORTH 24 PARGANAS AGRICULTURE AGR/Q4303 Poultry farm manager [email protected] 9434102419 30 Parganas, State : West Bengal Poultry feed, food Vill +PO+PS : Bagdah, Dist : North 24 NORTH 24 PARGANAS AGRICULTURE AGR/Q4305 safety and labelling [email protected] 9434102419 30 Parganas, State : West Bengal supervisor Vill +PO+PS : Bagdah, Dist : North 24 NORTH 24 PARGANAS AGRICULTURE AGR/Q4501 Goat Farmer [email protected] 9434102419 30 Parganas, State : West Bengal Prafulla Kanan, VIP Road, Kestopur, NORTH 24 PARGANAS AGRICULTURE AGR/Q4904 Aqua culture worker [email protected] 9830037376 200 Kolkata - 700101 Fisheries Extension BARASAT, Stn. Rd, Near Platform no1, 7 NORTH 24 PARGANAS AGRICULTURE AGR/Q5107 [email protected] 9331040169 90 Associate K.N.C. Rd., Kol-124 Gurukul Edutech Duttapukur,Vill : Agriculture Extension NORTH 24 PARGANAS AGRICULTURE AGR/Q7601 Gangapur, P.O. & P.S. Duttapukur, North [email protected] 9051352337 30 Service Provider 24 Parganas Pin 743248 Gurukul Edutech, Haroa,Vill & P.O. Agriculture Extension NORTH 24 PARGANAS AGRICULTURE AGR/Q7601 Gopalpur,P.S. Haroa Dist. North 24 [email protected] 9051352337 60 Service Provider Parganas APPAREL, MADE-UPS & Sewing Machine Plot No - 3B, Block-LA, Sector-III, Salt NORTH 24 PARGANAS AMH/Q0301 [email protected] 9679669547 50 HOME FURNISHING Operator Lake, Kolkata - 700098 APPAREL, MADE-UPS & Sewing Machine Jhautalamore, Post. -

North 24-Parganas, Has Been Divided Geographically Into Three Parts, E.G

For Official Use Only MAP OF NORTH 24 PARGANAS DISTRICT DISASTER VULNERABILITY MAPS PUBLISHED BY GOVERNMENT OF INDIA CONTENTS Sl. No. Subject Page No. 1. Map Of North 24 Parganas District i 2. Contents Ii 3. Foreword iii 4. North 24 Parganas At A Glance 1 5. Communication Plan 7 6. History Of Disaster Vulnerability in North 24 Parganas 30 7. Rainfall 34 8. Control Room 36 9. Chapter 1 Introduction To DM Plan 37 10. Chapter 2 HVCRA Hazard, Vulnerability, Capacity And Risk Assessment 38 11. Chapter 3 Institutional Arrangements 45 12. Chapter 4 Prevention And Mitigation 47 13. Chapter 5 Preparedness Measures 49 14. Chapter 6 Capacity Building And Training Measures 53 15. Chapter 7 Response And Relief Measures 57 16. Chapter 8 Reconstruction, Rehabilitation And Recovery Measures 60 17. Chapter 9 Financial Resources For Implementation Of DDMP 63 Chapter 10 Procedure And Methodology For Monitoring, Evaluation, Updation And 18. 64 Maintenance Of DDMP 19. Chapter 11 Coordination Mechanism For Implementation Of DDMP 65 20. Chapter 12 Standard Operating Procedures (Sops) And Checklist 66 21. Irrigation Plan 68 22. Flood Preparedness Horticulture Department Plan 88 23. Contingent Plan of Schools 89 24. Flood Preparedness PHE Department Plan 90 25. Flood Preparedness Animal Resource Development Dept. Plan 92 26. Department of Health Plan 95 27. District controller of Food and supply Plan 99 28. Department of Forest Plan 100 29. WBSEDCL Plan 102 30. Department of Agriculture Plan 103 31. Department of Fisheries Plan 114 Annexure Ambulance 120 Block Hospitals 122 Boats 123 Flood shelter at Block Level Government 128 32. -

Volunteer Name with Reg No State (District) (Block) Mobile No APSANA KHATUN (61467) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Fanside

Volunteer Name with Reg No State (District) (Block) Mobile no APSANA KHATUN (61467) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Fansidewa) 9547651060 RABINA KHAWAS (64657) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Kalimpong-I) 7586094862 NITSHEN TAMANG (64650) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Takda) 9564994554 ARBIND SUBBA (61475) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Takda) 7001894077 SANTOSH KUMAR PASWAN (61593) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Nakshalbari) 8917830020 SAMIRAN KHATUN (64837) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Fansidewa) 7407206018 ANISHA THAKURI (64645) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Bijanbari) 7679456517 BIKASH SINGHA (61913) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Kharibari) 9064394568 PUSKAR TAMANG (64607) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Garubathan) 8436112429 ANIP RAI (61968) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Bijanbari) 7047337757 SUDIBYA RAI (61976) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Kalimpong-II) 8944824498 DICHEN LAMA (64633) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Kalimpong-II) 9083860892 YOGESH N SARKI (62019) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Kurseong) 7478305517 BIJAYA LAXMI SINGH (61586) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Matigara) 9932839481 SAGAR RAI (64619) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Garubathan) 7029143177 DEEPTI BISWAKARMA (61491) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Garubathan) 9734902283 ANMOL CHHETRI (61496) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Kurseong) 9593951858 BIJAY CHANDRA SHARMA (61470) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Kalimpong-I) 9233666950 KHAGESH ROY (61579) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Nakshalbari) 8759721171 SANGAM SUBBA (61462) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Mirik) 8972908640 LIMESH TAMANG (64627) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Bijanbari) 9679167713 ANUSHILA LAMA TAMANG (61452) WEST BENGAL -

North 24 Parganas

Present Place of District Sl No Name Post Posting DPMU, DH&FWS, CMOH OFFICE N 24 Pgs 1 PRATAP MAJUMDER DPC NORTH 24 PARGANAS, Barasat DPMU, DH&FWS, CMOH OFFICE N 24 Pgs 2 JAYANTA KUMAR PAL DAM NORTH 24 PARGANAS, Barasat DPMU, DH&FWS, CMOH OFFICE N 24 Pgs 3 Goutam Maity DSM NORTH 24 PARGANAS, Barasat DPMU, DH&FWS, CMOH OFFICE N 24 Pgs 4 SAMIRAN KARMAKAR Account Assistant NORTH 24 PARGANAS, Barasat DPMU, DH&FWS, CMOH OFFICE N 24 Pgs 5 APAN SEN Computer Assistant NORTH 24 PARGANAS, Barasat DPMU, DH&FWS, NORTH 24 N 24 Pgs 6 KRISHNA BISWAS AE PARGANAS, Barasat DPMU, DH&FWS, NORTH 24 N 24 Pgs 7 PRONAB HALDER SAE PARGANAS, Barasat N 24 Pgs 8 Dr.Sudip Sarkar GDMO Amdanga BPHC N 24 Pgs 9 Dr.Mudhusudhan Mirdha GDMO Jogeshgunj PHC N 24 Pgs 10 Dr.Mahuya Saha GDMO Goshpur BPHC N 24 Pgs 11 Dr Mannaf Ali GDMO Nazat PHC Dr.Kushik Das GDMO Madhayam Gram N 24 Pgs 12 RH Dr. Surendra Nath Mondal GDMO Bagbon Saiberia N 24 Pgs 13 PHC N 24 Pgs 14 Dr.Debansu Sarkar GDMO Nataberia PHC N 24 Pgs 15 Dr.Soumyajit Chakrabarti GDMO PallaPHC N 24 Pgs 16 Dr.Pusun kr Ghosh GDMO Bandipur BPHC N 24 Pgs 17 Dr.Asim Sarkar GDMO Bandipur BPHC N 24 Pgs 18 Dr.Santunu Sarkar GDMO Barunhat PHC N 24 Pgs 19 Dr.Partha Sarathi Biswas GDMO Routara PHC N 24 Pgs 20 Dr.Shamol Kanta Kundu GDMO Chad para BPHC N 24 Pgs 21 Dr.Pradip Kr Dutta GDMO Chad para BPHC N 24 Pgs 22 Dr.Manoj Mondal GDMO Dharampur PHC N 24 Pgs 23 Dr.Dilip Biswas GDMO Minakha RH N 24 Pgs 24 Dr.Indranil Khatua GDMO Rajarhat BPHC N 24 Pgs 25 Dr.Dilip Patra GDMO Harowa BPHC N 24 Pgs 26 Dr.