We Change the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer Reading by Grade/Title Fifth and Sixth Grades 2018 Summer

Summer Reading By Grade/Title Fifth and Sixth Grades 2018 Summer Reading Requirements Choose 2 The Evolution of Calpurnia Tate Jacqueline Kelly 830L Fish in a Tree Lynda Mullaly Hunt 550L Inside Out and Back Again Thanhha Lai 800L Out of My Mind Sharon Draper 700L My Side of the Mountain Jean Craighead George 810L Auggie & Me: Three Wonder Stories RJ Palacio 680L (Wonder is suggested before reading this book) The Phantom Tollbooth Norton Juster 1000L Pax Sara Pennypacker 760L Sticks & Stones Abby Cooper 750L Rules Cynthia Lord 670L Ms. Bixby’s Last Day John David Anderson 800L Nine, Ten: A September 11 Story Nora Raleigh Baskin 730L Tuck Everlasting Natalie Babbitt 770L Where the Red Fern Grows Wilson Rawls 700L Seventh Grade: Required reading: Flying Lessons and Other Short Stories edited by Ellen Oh Book of choice list: Classics that Mrs. McDaniel loves: 1. Walk Two Moons by Sharon Creech 2. The Westing Game by Ellen Raskin 3. A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle 4. Roll of Thunder Hear My Cry by Mildred D. Taylor 5. Hatchet by Gary Paulson 6. The Watsons go to Birmingham by Christopher Paul Curtis Modern YA books: 7. Holes by Lois Sachar 8. The Wednesday Wars by Gary D. Schmidt 9. Hoot by Carl Hiaasen 10. Code Talker by Joseph Bruchac 11. A Monster Calls by Patrick Ness Eighth Grade: Required reading: Brown Girl Dreaming by Jaqueline Woodson Book of choice list: Classics that Mrs. McDaniel loves: 1. Anne of Green Gables by L.M. Montgomery 2. The Hobbit by J.R.R. -

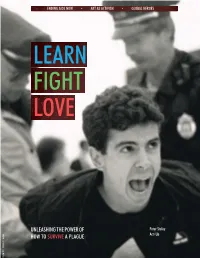

LFL MAG Medweb.Pdf

ENDING AIDS NOW * ART AS ACTIVISM * GLOBAL HEROES LEARNLEARN FIGHT LOVE FIGHT LOVE UNLEASHING THE POWER OF Peter Staley PHOTO: © William Lucas Walker PHOTO: HOW TO SURVIVE A PLAGUE Acts Up HTSAPxm_poster_ACADEMY_Jan_2013_v1 1/16/13 3:23 PM Page 1 PHOTO: © Karine Laval © Karine PHOTO: discipline removed from the real world A LETTER FROM of ordinary people. It took up to a dozen years for a new drug to be tested and THE FILMMAKER released. Even after the onset of the AIDS epidemic, with its grim prognosis of just How to Survive a Plague bears witness. 18 months, a hermetic sense of academic The film documents what I saw with my sluggishness prevailed. They knocked on own eyes in those first long dark days of doors at the NIH and FDA, then knocked the worst plague in America—it shows them down when their pleas were both the tragedy and the brilliance not answered. leading up to 1996 when effective That’s how the “inside” forces flooded medication finally made it possible to in and demanded a place at the table think of HIV/AIDS as a chronic condition, for patients and their advocates in every like diabetes. I witnessed all this in my role aspect of medicine and science. Their as a journalist, not an activist. Instead of a task was daunting. In order to become bullhorn or placard, I carried a notepad full partners in the research, they had to and pen. There I am in the background of become experts themselves. I watched these frames. You can see brief glimpses Peter, Mark, Garance, David, and the of me nearly hidden in those crowds of others turn to textbooks and teach activists, pressed against the walls of themselves the fundamentals of science— their meetings or counting their heads as quizzing one another on the basics police officers carted them off, trying to of immunology and virology, cellular stay out of their way. -

TRUE/FALSE FILM FEST 2020 FEATURE FILMS 45365 | Dir. Bill & Turner Ross; 2009; 94 Min (United States) Prod. Bil & Turner

TRUE/FALSE FILM FEST 2020 FEATURE FILMS 45365 | Dir. Bill & Turner Ross; 2009; 94 min (United States) Prod. Bil & Turner Ross It’s 69 degrees and sunny at the Shelby County Fair. Long-haul trucks whiz by, a solo trumpeter takes the stage, and downtown Sidney’s tree-lined main street disappears into the rearview mirror in a stunning opening sequence. Dazzling and earnest, this debut film by Bill and Turner Ross uses the sounds of public radio, marching bands, and police scanners to cleverly collapse time and space, taking us from the weekend weather to a live interview with the 4-H queen first runner-up. Here, in the heart of the Ohio valley, spotted horses prance in their stables, teenage boys race in junk derbies and local politicians canvass door-to-door for their reelections. Filmed over the course of nine months, the camera moves deftly between flirting, freak shows, and football, reminding us that the everyday is extraordinary and “it’s always fun to watch little kids run around with their hogs.” (JA) Aswang | Dir. Alyx Ayn Arumpac; 2019; 85 min (Philippines) Prod. Armi Rae Cacanindin Blood stains the sidewalks as President Duerte undertakes what he calls the “neutralization of illegal drug personalities,” but what citizens of Manilla have come to know as nothing less than a killing spree. In her feature-length debut, Director Alyx Arympac sensitively approaches the trauma that has befallen her subjects: a journalist who fights the government’s lawlessness; a restrained coroner; a brave missionary’s brother who tries to comfort the bereaved families of the dead; and Jomari, who lives on the streets after his parents were jailed. -

GORE VIDAL the United States of Amnesia

Amnesia Productions Presents GORE VIDAL The United States of Amnesia Film info: http://www.tribecafilm.com/filmguide/513a8382c07f5d4713000294-gore-vidal-the-united-sta U.S., 2013 89 minutes / Color / HD World Premiere - 2013 Tribeca Film Festival, Spotlight Section Screening: Thursday 4/18/2013 8:30pm - 1st Screening, AMC Loews Village 7 - 3 Friday 4/19/2013 12:15pm – P&I Screening, Chelsea Clearview Cinemas 6 Saturday 4/20/2013 2:30pm - 2nd Screening, AMC Loews Village 7 - 3 Friday 4/26/2013 5:30pm - 3rd Screening, Chelsea Clearview Cinemas 4 Publicity Contact Sales Contact Matt Johnstone Publicity Preferred Content Matt Johnstone Kevin Iwashina 323 938-7880 c. office +1 323 7829193 [email protected] mobile +1 310 993 7465 [email protected] LOG LINE Anchored by intimate, one-on-one interviews with the man himself, GORE VIDAL: THE UNITED STATS OF AMNESIA is a fascinating and wholly entertaining tribute to the iconic Gore Vidal. Commentary by those who knew him best—including filmmaker/nephew Burr Steers and the late Christopher Hitchens—blends with footage from Vidal’s legendary on-air career to remind us why he will forever stand as one of the most brilliant and fearless critics of our time. SYNOPSIS No twentieth-century figure has had a more profound effect on the worlds of literature, film, politics, historical debate, and the culture wars than Gore Vidal. Anchored by intimate one-on-one interviews with the man himself, Nicholas Wrathall’s new documentary is a fascinating and wholly entertaining portrait of the last lion of the age of American liberalism. -

Ratti AP Lang Summer Assignments 2020-2021

Ratti AP Lang Summer Assignments 2020-2021 May 1, 2020 Dear Future Student, Hello, and welcome! I’m so excited that you have chosen to take one of the most stimulating and rewarding classes offered at MCHS. As I’m sure you know, it’s going to be a challenge, but I’ll be with you every step of the way. When we challenge ourselves, we grow. AP Language and Composition is going to help you grow as a reader and a writer, and, I suspect, even as a person. I can say that teaching this class has been a joy as well as a tremendous growth opportunity for me. We are in it together. The summer of 2020 looks like it is going to be challenging, but I have provided these assignments in hopes that you will be able to continue your education in enjoyable and productive ways while you are stuck at home. I have made an effort to include resources and suggestions so that students at all levels of income and technology access can complete the assignments successfully. If you have any difficulty or concern, please contact me as soon as possible. You may reach me by email, Remind, by posting on Teams, or by calling the school at (423) 745-4142. I will make every effort to make sure any student who wants to participate is able to. The biggest part of your work for me will be the Knowledge Builders assignment, a fact-gathering, critical thinking challenge to broaden your knowledge of the world around you. -

Documentary Movies

Libraries DOCUMENTARY MOVIES The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 10 Days that Unexpectedly Changed America DVD-2043 56 Up DVD-8322 180 DVD-3999 60's DVD-0410 1-800-India: Importing a White-Collar Economy DVD-3263 7 Up/7 Plus Seven DVD-1056 1930s (Discs 1-3) DVD-5348 Discs 1 70 Acres in Chicago: Cabrini Green DVD-8778 1930s (Discs 4-5) DVD-5348 Discs 4 70 Acres in Chicago: Cabrini Green c.2 DVD-8778 c.2 1964 DVD-7724 9/11 c.2 DVD-0056 c.2 1968 with Tom Brokaw DVD-5235 9500 Liberty DVD-8572 1983 Riegelman's Closing/2008 Update DVD-7715 Abandoned: The Betrayal of America's Immigrants DVD-5835 20 Years Old in the Middle East DVD-6111 Abolitionists DVD-7362 DVD-4941 Aboriginal Architecture: Living Architecture DVD-3261 21 Up DVD-1061 Abraham and Mary Lincoln: A House Divided DVD-0001 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 Absent from the Academy DVD-8351 24 City DVD-9072 Absolutely Positive DVD-8796 24 Hours 24 Million Meals: Feeding New York DVD-8157 Absolutely Positive c.2 DVD-8796 c.2 28 Up DVD-1066 Accidental Hero: Room 408 DVD-5980 3 Times Divorced DVD-5100 Act of Killing DVD-4434 30 Days Season 3 DVD-3708 Addicted to Plastic DVD-8168 35 Up DVD-1072 Addiction DVD-2884 4 Little Girls DVD-0051 Address DVD-8002 42 Up DVD-1079 Adonis Factor DVD-2607 49 Up DVD-1913 Adventure of English DVD-5957 500 Nations DVD-0778 Advertising and the End of the World DVD-1460 -

LGBTQA+ History Resource Guide

LGBTQA+ History Resource Guide CW: The following resources contain discussions of Videos homophobia, transphobia, White Supremacy, “LGBT History: What’s The Point?” – Novara racism, colonialism, hate crimes, violence, policing Media and police violence, and sexual assault. “Black History Month: Gay Edition” – NoMoreDownLow Looking for more information or resources about LGBTQA+ history? “Pioneering Icon Paris Dupree Explaining the History of the Harlem Drag Ball Scene” Note: These resources are primarily focused on LGBTQA+ history in the United States. “Mexico’s Dance of the 41 Is a Lesson in Queer History” – Hornet Articles “Introduction to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, “Being Two Spirit: A Brief History of Queer Transgender, and Queer History (LGBTQ Native Culture” – Splinter Video History) in the United States” – Leisa Meyer and Helis Sikk “LGBT History by the Decades: The Roaring Twenties” – AreTheyGay “LGBTQ History” – GLSEN “LGBT History by the Decades: The World At “The History of Queer History: One Hundred War” – AreTheyGay Years of the Search for Shared Heritage” – Gerard Koskovich “LGBT History By The Decades: Age of Conformity” – AreTheyGay “Breathing Fire: Remembering Asian Pacific American Activism in Queer History” – Amy “LGBT History By The Decades: The Golden Sueyoshi Age” – AreTheyGay “Timeline of Asian and Pacific Islander diasporic “LGBT History By The Decades: Before LGBT history” – Wikipedia Stonewall” – AreTheyGay “A Forgotten Latina Trailblazer: LGBT Activist Sylvia Rivera” – Raul A. Reyes Sylvia Rivera and “Black LGBT -

How to Survive a Plague Discussion Guide

www.influencefilmforum.com How to Survive a Plague Discussion Guide Director: David France Year: 2012 Time: 110 min You might know this director from: HOW TO SURVIVE A PLAGUE is David France’s first feature-length documentary film. FILM SUMMARY HOW TO SURVIVE A PLAGUE addresses the pandemic death associated with HIV and AIDS in 1980’s America. Without any explanation or assistance, victims were never offered a real diagnosis. Finding themselves in the midst of a biased and unhelpful community, senators, mayors, even the U.S. President claimed that sufficient action was being taken. Meanwhile, victims went blind and withered away until a group of self-made activists, many who were victims themselves, took matters into their hands to instigate real change. Using amateur videography from a 30-year span, HOW TO SURVIVE A PLAGUE chronicles their trials and successes. When North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms stood before lawmakers and stated, “There is nothing gay about these people, engaging in incredibly offensive and revolting conduct that has led to the proliferation of AIDS,” homophobia and its nasty effects had fatal implications. Hospitals were given incentives not to diagnose AIDS patients, and scientists were not pressed to find a cure. Thus, ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) and later TAG (Treatment Action Group) were formed, making the impossible possible, demanding more research and drug availability for victims of this horrendously virulent disease. Incredibly moving and thorough, HOW TO SURVIVE A PLAGUE follows brave activists as they tirelessly present their case across the U.S. and Europe. This film presents a living example of the power of political activism, which in this case has arguably saved over 6,000,000 lives. -

35 Years of Nominees and Winners 36

3635 Years of Nominees and Winners 2021 Nominees (Winners in bold) BEST FEATURE JOHN CASSAVETES AWARD BEST MALE LEAD (Award given to the producer) (Award given to the best feature made for under *RIZ AHMED - Sound of Metal $500,000; award given to the writer, director, *NOMADLAND and producer) CHADWICK BOSEMAN - Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom PRODUCERS: Mollye Asher, Dan Janvey, ADARSH GOURAV - The White Tiger Frances McDormand, Peter Spears, Chloé Zhao *RESIDUE WRITER/DIRECTOR: Merawi Gerima ROB MORGAN - Bull FIRST COW PRODUCERS: Neil Kopp, Vincent Savino, THE KILLING OF TWO LOVERS STEVEN YEUN - Minari Anish Savjani WRITER/DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Robert Machoian PRODUCERS: Scott Christopherson, BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE MA RAINEY’S BLACK BOTTOM Clayne Crawford PRODUCERS: Todd Black, Denzel Washington, *YUH-JUNG YOUN - Minari Dany Wolf LA LEYENDA NEGRA ALEXIS CHIKAEZE - Miss Juneteenth WRITER/DIRECTOR: Patricia Vidal Delgado MINARI YERI HAN - Minari PRODUCERS: Alicia Herder, Marcel Perez PRODUCERS: Dede Gardner, Jeremy Kleiner, VALERIE MAHAFFEY - French Exit Christina Oh LINGUA FRANCA WRITER/DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Isabel Sandoval TALIA RYDER - Never Rarely Sometimes Always NEVER RARELY SOMETIMES ALWAYS PRODUCERS: Darlene Catly Malimas, Jhett Tolentino, PRODUCERS: Sara Murphy, Adele Romanski Carlo Velayo BEST SUPPORTING MALE BEST FIRST FEATURE SAINT FRANCES *PAUL RACI - Sound of Metal (Award given to the director and producer) DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Alex Thompson COLMAN DOMINGO - Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom WRITER: Kelly O’Sullivan *SOUND OF METAL ORION LEE - First -

Documentary Movies

Libraries DOCUMENTARY MOVIES The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 10 Days that Unexpectedly Changed America DVD-2043 500 Nations DVD-0778 10 Days to D-Day DVD-0690 500 Years Later DVD-5438 180 DVD-3999 56 Up DVD-8322 1-800-India: Importing a White-Collar Economy DVD-3263 60's DVD-0410 1930s (Discs 1-3) DVD-5348 Discs 7 Up/7 Plus Seven DVD-1056 1930s (Discs 4-5) DVD-5348 Discs 7 Years DVD-4399 1964 DVD-7724 70 Acres in Chicago: Cabrini Green DVD-8778 1968 with Tom Brokaw DVD-5235 70 Acres in Chicago: Cabrini Green c.2 DVD-8778 c.2 1983 Riegelman's Closing/2008 Update DVD-7715 70's Dimension DVD-1568 1993 World Trade Center Bombing DVD-1891 9/11 c.2 DVD-0056 c.2 20 Years Old in the Middle East DVD-6111 900 Women DVD-2068 DVD-4941 9500 Liberty DVD-8572 21 Up DVD-1061 Abandoned: The Betrayal of America's Immigrants DVD-5835 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 Abolitionists DVD-7362 24 City DVD-9072 Aboriginal Architecture: Living Architecture DVD-3261 24 Hours 24 Million Meals: Feeding New York DVD-8157 Abraham and Mary Lincoln: A House Divided DVD-0001 28 Up DVD-1066 Absent from the Academy DVD-8351 3 Times Divorced DVD-5100 Absolutely Positive DVD-8796 30 Days Season 3 DVD-3708 Absolutely Positive c.2 DVD-8796 c.2 35 Up DVD-1072 Accidental Hero: Room 408 DVD-5980 4 Little Girls DVD-0051 Act of Killing DVD-4434 42 Up DVD-1079 Addicted to Plastic DVD-8168 -

IB FILM SL & HL Year 1 Mr. London SUMMER READING

IB FILM SL & HL year 1 Mr. London SUMMER READING & VIEWING WHAT YOU WILL NEED: ● Either a public library card (FREE)/a Netflix, Hulu, or FilmStruck account ($7.99 - $11 month - but usually these services offer a free trial!) ● Internet access ● A journal/notebook for jotting down observations ● Mr. London’s email: o [email protected] REQUIREMENTS (to be completed by the first day of class in August): 1) Select 10 films from the list provided (though watch as many as you can!). You MUST watch 1 film from each of the categories, and the rest is your choice. 2) Write a response (1-2 pages each) for each film. a. If you have access to a computer/laptop, you may type up your responses in a continuing Google document, 12 point Open Sans, and double-spaced (to be shared with me by the first day of class). b. Each film’s response should be in paragraph form and should be about your observations, insights, comments, and connections that you are making between the readings and the films you watch. c. Also, your responses will be much richer if you research information about the films you watch before you write – simply stating your opinion will not give you much material to write about, and you will not be able to go beyond your own opinion – for example, read online articles/reviews about each film by scholars/critics (New York Times, The Guardian, rogerebert.com, IMDB.com, filmsite.org, etc). You can also watch awesome video essays on YouTube. Click HERE for a great list of YouTube Channels. -

Seeing What the Patrimony Didn't Save

4 SEEING WHAT THE PATRIMONY DIDN’T SAVE Alternative Stewardship of the Activist Media Archive—A Conversation between Alexandra Juhasz and Theodore Kerr Alexandra Juhasz Theodore Kerr ou know how it is when people die? Folks always be putting words in “Yyour mouth. This way, if I don’t say it on tape, I ain’t say it, baby.” These words are spoken by an actress who is playing an expectant grandmother living with HIV in a video. The tape is most likely from the mid-1980s and was created by Bebashi, an AIDS Service Organization in Philadelphia.1 The actress speaks in the final chapter from a series of short vignettes that focus on the linked impact of domestic violence, poverty, drugs, and HIV/AIDS on black women. In this section, a pregnant daughter is recording her mother’s life story for “the sake of posterity.” The soon-to-be grandmother does not believe that she will live long enough to share her life story with her grand- child. We see the grandmother through the camera, the eye of her daughter. Occasionally—often when the grandmother expresses doubt about telling her story on tape—we get a shot from a different, more distant perspective: of the two women sitting across from each other, the camera now acting as bridge between them, and between their story and our witness. Titled Grandma’s Legacy, the vignette is one example of the numerous activist videos made in the United States during the early response to HIV. 88 | InsUrgent Media from the Front Figure 4.1.