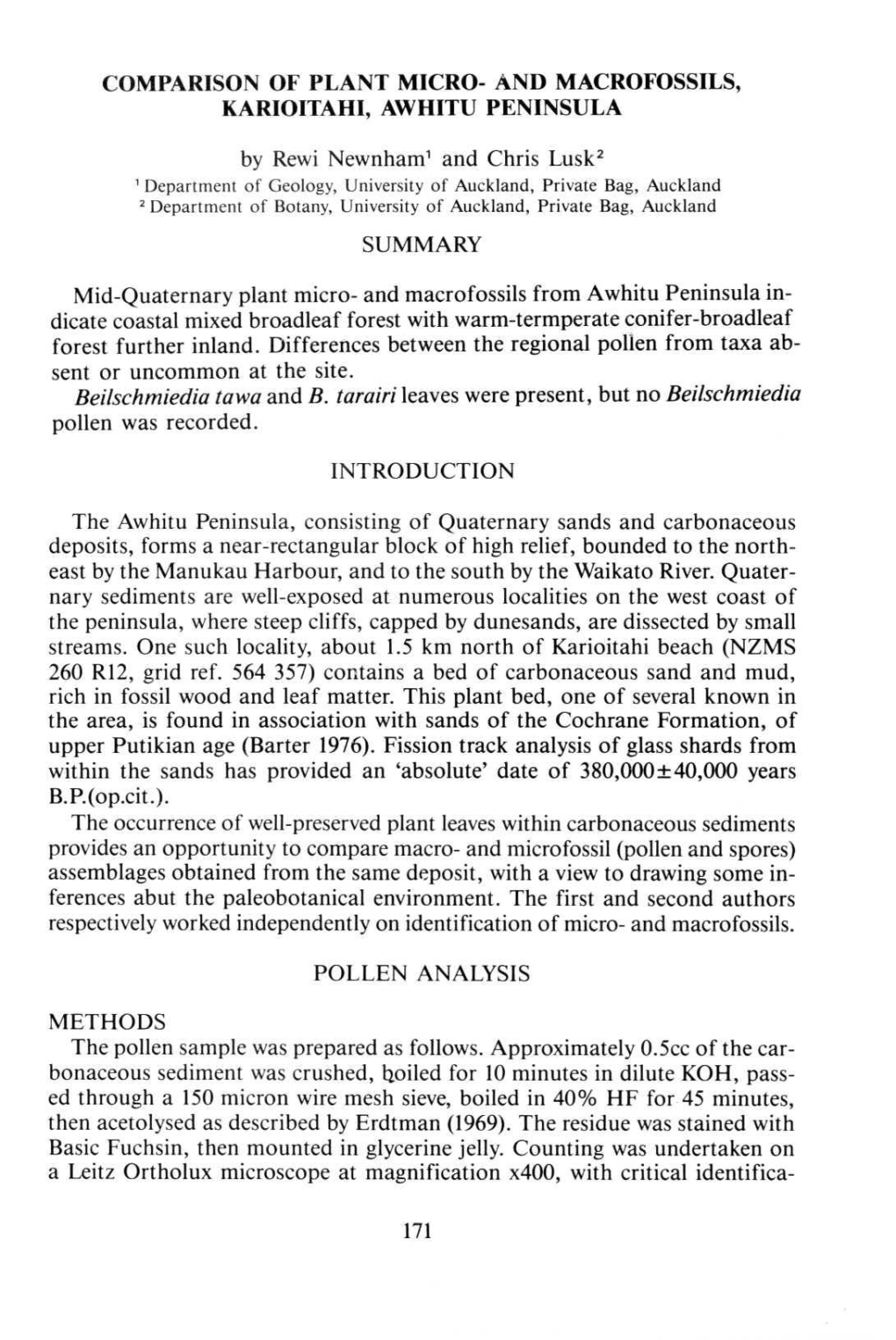

Comparison of Plant Micro- and Macrofossils, Karioitahi, Awhitu Peninsula

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plant Macrofossil Evidence for an Early Onset of the Holocene Summer Thermal Maximum in Northernmost Europe

ARTICLE Received 19 Aug 2014 | Accepted 27 Feb 2015 | Published 10 Apr 2015 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms7809 OPEN Plant macrofossil evidence for an early onset of the Holocene summer thermal maximum in northernmost Europe M. Va¨liranta1, J.S. Salonen2, M. Heikkila¨1, L. Amon3, K. Helmens4, A. Klimaschewski5, P. Kuhry4, S. Kultti2, A. Poska3,6, S. Shala4, S. Veski3 & H.H. Birks7 Holocene summer temperature reconstructions from northern Europe based on sedimentary pollen records suggest an onset of peak summer warmth around 9,000 years ago. However, pollen-based temperature reconstructions are largely driven by changes in the proportions of tree taxa, and thus the early-Holocene warming signal may be delayed due to the geographical disequilibrium between climate and tree populations. Here we show that quantitative summer-temperature estimates in northern Europe based on macrofossils of aquatic plants are in many cases ca.2°C warmer in the early Holocene (11,700–7,500 years ago) than reconstructions based on pollen data. When the lag in potential tree establishment becomes imperceptible in the mid-Holocene (7,500 years ago), the reconstructed temperatures converge at all study sites. We demonstrate that aquatic plant macrofossil records can provide additional and informative insights into early-Holocene temperature evolution in northernmost Europe and suggest further validation of early post-glacial climate development based on multi-proxy data syntheses. 1 Department of Environmental Sciences, ECRU, University of Helsinki, P.O. Box 65, Helsinki FI-00014, Finland. 2 Department of Geosciences and Geography, University of Helsinki, P.O. Box 65, Helsinki FI-00014, Finland. -

NEWSLETTER NUMBER 84 JUNE 2006 New Zealand Botanical Society

NEW ZEALAND BOTANICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER NUMBER 84 JUNE 2006 New Zealand Botanical Society President: Anthony Wright Secretary/Treasurer: Ewen Cameron Committee: Bruce Clarkson, Colin Webb, Carol West Address: c/- Canterbury Museum Rolleston Avenue CHRISTCHURCH 8001 Subscriptions The 2006 ordinary and institutional subscriptions are $25 (reduced to $18 if paid by the due date on the subscription invoice). The 2006 student subscription, available to full-time students, is $9 (reduced to $7 if paid by the due date on the subscription invoice). Back issues of the Newsletter are available at $2.50 each from Number 1 (August 1985) to Number 46 (December 1996), $3.00 each from Number 47 (March 1997) to Number 50 (December 1997), and $3.75 each from Number 51 (March 1998) onwards. Since 1986 the Newsletter has appeared quarterly in March, June, September and December. New subscriptions are always welcome and these, together with back issue orders, should be sent to the Secretary/Treasurer (address above). Subscriptions are due by 28th February each year for that calendar year. Existing subscribers are sent an invoice with the December Newsletter for the next years subscription which offers a reduction if this is paid by the due date. If you are in arrears with your subscription a reminder notice comes attached to each issue of the Newsletter. Deadline for next issue The deadline for the September 2006 issue is 25 August 2006 Please post contributions to: Joy Talbot 17 Ford Road Christchurch 8002 Send email contributions to [email protected] or [email protected]. Files are preferably in MS Word (Word XP or earlier) or saved as RTF or ASCII. -

Standard Procedures for the Assessment and Mitigation of Adverse Impacts to Paleontological Resources

Standard Procedures for the Assessment and Mitigation of Adverse Impacts to Paleontological Resources Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Impact Mitigation Guidelines Revision Committee Abstract Fossils are nonrenewable paleontological resources that are subject to impacts from land development. Procedures are presented for evaluating the potential for impacts of a proposed action on paleontological resources and for mitigating those impacts. Impact mitigation includes pre-project survey and salvage, monitoring and screen washing during excavation to salvage fossils, conservation and inventory, and final reports and specimen curation. The objective of these procedures is to offer standard methods for assessing potential impacts to fossils and mitigating these impacts. Introduction Fossils are nonrenewable paleontological resources that are afforded protection by federal, state, and local environmental laws and regulations. The Paleontological Resources Preservation Act (PRPA) of 2009 calls for uniform policies and standards that apply to fossils on all federal public lands. All federal land management agencies are required to develop regulations that satisfy the stipulations of the PRPA. Section 6302 of the PRPA mandates that federal agencies "shall manage and protect paleontological resources on Federal land using scientific principles and expertise." Thus, federal agencies need the help of the professional paleontological community in the formulation and implementation of these PRPA- mandated policies and regulations. The potential for destruction or degradation of paleontological resources on both public and private lands selected for development under the jurisdiction of various governmental planning agencies is recognized. The standard procedures below are intended to be applicable to both private and public lands under the jurisdiction of local, city, county, regional, state, and federal agencies. -

Ascarina Lucida Var. Lanceolata

Ascarina lucida var. lanceolata COMMON NAME Kermadec Islands Hutu SYNONYMS Ascarina lanceolata Hook.f. FAMILY Chloranthaceae AUTHORITY Ascarina lucida var. lanceolata (Hook.f.) Allan FLORA CATEGORY Vascular – Native ENDEMIC TAXON Yes ENDEMIC GENUS No Hutu. Photographer: Bec Stanley ENDEMIC FAMILY No STRUCTURAL CLASS Trees & Shrubs - Dicotyledons NVS CODE ASCLVL CHROMOSOME NUMBER 2n = 26 CURRENT CONSERVATION STATUS Hutu. Photographer: Bec Stanley 2012 | At Risk – Naturally Uncommon | Qualifiers: IE, OL PREVIOUS CONSERVATION STATUSES 2009 | At Risk – Naturally Uncommon | Qualifiers: IE, OL 2004 | Not Threatened BRIEF DESCRIPTION Small bushy tree of upland Kermadec Islands. Leaves narrow and tapering to a narrow tip and with coarse black- tipped teeth on margins. Flowers in clusters of spikes. Fruit small, white. DISTRIBUTION Endemic. Kermadec Islands, Raoul Island only. HABITAT One of the characteristic trees of the wet forests of Raoul Island which are mostly found above 245m. However, in the ravines this tree may extend down to almost sea level. In the wet forest it is mostly a subcanopy tree which co- associates with Coprosma acutifolia, Pseudopanax kermadecensis, Melicytus aff. ramiflorus and on occasion Boehmeria australis subsp. dealbata. Occasionally, such as on the ridge lines and crater rim it may form part of the forest canopy. FEATURES Glabrous gynodioecious tree up to 15 m tall. Trunk up to 500 mm diameter. Bark greyish-white. Branchlets slender, striate, initially pale green maturing dark green to emerald green. Interpetiolar stipules conspicuous, comprising 3 1.2-2.6 mm long pale pink to red, filaments; these connate near base, behind which are 3-6 smaller hyaline filaments. Petioles up to 15-20 mm long, lamina subcoriacous, somewhat fleshy, 50-100 × 10-30 mm, green, emerald green to dark green above, paler beneath, serrations weakly pigmented, pink to pale maroon often fading into pale pink spotting, narrowly lanceolate, lanceolate, lanceolate- oblong to narrowly elliptic, acuminate to acute. -

PAL-3, Paleontological Resources Mitigation And

DOCKETED Docket Number: 16-AFC-01C Project Title: Stanton Energy Reliability Center - Compliance TN #: 226417 PAL-3, Paleontological Resources Mitigation and Monitoring Program Document Title: (PRMMP) Description: N/A Filer: Marichka Haws Organization: California Energy Commission Submitter Role: Commission Staff Submission Date: 1/31/2019 11:24:15 AM Docketed Date: 1/31/2019 STATE OF CALIFORNIA – NATURAL RESOURCES AGENCY GAVIN NEWSOM, Governor CALIFORNIA ENERGY COMMISSION 1516 NINTH STREET SACRAMENTO, CA 95814-5512 www.energy.ca.gov January 14, 2019 Greg Lamberg Compliance Manager W Power 650 Bercut Drive, Suite A Sacramento, CA 95811 SUBJECT: Stanton Energy Reliability Center (16-AFC-01C), PAL-3, Paleontological Resources Mitigation and Monitoring Program (PRMMP) Dear Mr. Lamberg, In accordance with PAL-3, the CPM has reviewed and approved the Paleontological Resources Mitigation and Monitoring Plan (PRMMP). If you have any questions or concerns, please contact John Heiser, Compliance Project Manager, at (916) 653-8236, or by fax to (916) 654-3882, or via e-mail at [email protected]. Sincerely, John Heiser Compliance Office Manager Siting, Transmission, & Environmental Protection Division CONDITION OF CERTIFICATION PAL- 3 Stanton Energy Reliability Center (16-AFC-01) Paleontological Resources Mitigation and Monitoring Plan Prepared for California Energy Commission November 2018 Orange County Office 27001 La Paz Road, Suite 230 Mission Viejo, CA 92691 The undersigned is the primary author of this document: Dr. W. Geoffrey Spaulding -

Grand Canyon National Park Centennial Paleontological Resource Inventory (Non-Sensitive Version)

Grand Canyon National Park Centennial Paleontological Resource Inventory (Non-Sensitive Version) Natural Resource Report NPS/GRCA/NRR—2020/2103 Vincent L. Santucci1 and Justin S. Tweet,2 editors 1National Park Service Geologic Resources Division 1849 “C” Street, NW Washington, D.C. 20240 2National Park Service 9149 79th St. S. Cottage Grove, Minnesota 55016 March 2020 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado Chapter 1. Introduction and Summary: The Paleontological Heritage of Grand Canyon National Park By Vincent L. Santucci1 1National Park Service Geologic Resources Division 1849 “C” Street, NW Washington, D.C. 20240 Throughout my life I have been bestowed the privilege of experiencing the world-renowned landscape and resources of the Grand Canyon from many perspectives and viewsheds (Figure 1-1). My first views were standing and taking photos from the many vantage points and overlooks along the North and South rims. I have enjoyed many hikes into the canyon with colleagues from the National Park Service (NPS) or with academic geologists and paleontologists. On a few occasions I ventured down and then back up the trails of the canyon with my children Sarah, Bethany, Luke, Jacob, Brianna and Abigail, often carrying one or more in my arms on the climb against gravity. I traversed by foot to the base of the canyon at Phantom Ranch and gained a greater appreciation for the geologic story preserved in the park strata. I have gazed intensely out the window of many commercial aircraft from above this geologic wonder of Earth, contemplating the geomorphic “grandeur” created over "Deep Time" and the artistry of processes perfected by “Mother Nature.” I pinch myself when I recall the opportunity when my friend Justin Tweet and I were granted permission to fly into the western portion of the Grand Canyon on a small NPS plane operated by a pilot from Lake Mead National Recreation Area. -

71St Annual Meeting Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Paris Las Vegas Las Vegas, Nevada, USA November 2 – 5, 2011 SESSION CONCURRENT SESSION CONCURRENT

ISSN 1937-2809 online Journal of Supplement to the November 2011 Vertebrate Paleontology Vertebrate Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Society of Vertebrate 71st Annual Meeting Paleontology Society of Vertebrate Las Vegas Paris Nevada, USA Las Vegas, November 2 – 5, 2011 Program and Abstracts Society of Vertebrate Paleontology 71st Annual Meeting Program and Abstracts COMMITTEE MEETING ROOM POSTER SESSION/ CONCURRENT CONCURRENT SESSION EXHIBITS SESSION COMMITTEE MEETING ROOMS AUCTION EVENT REGISTRATION, CONCURRENT MERCHANDISE SESSION LOUNGE, EDUCATION & OUTREACH SPEAKER READY COMMITTEE MEETING POSTER SESSION ROOM ROOM SOCIETY OF VERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS SEVENTY-FIRST ANNUAL MEETING PARIS LAS VEGAS HOTEL LAS VEGAS, NV, USA NOVEMBER 2–5, 2011 HOST COMMITTEE Stephen Rowland, Co-Chair; Aubrey Bonde, Co-Chair; Joshua Bonde; David Elliott; Lee Hall; Jerry Harris; Andrew Milner; Eric Roberts EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Philip Currie, President; Blaire Van Valkenburgh, Past President; Catherine Forster, Vice President; Christopher Bell, Secretary; Ted Vlamis, Treasurer; Julia Clarke, Member at Large; Kristina Curry Rogers, Member at Large; Lars Werdelin, Member at Large SYMPOSIUM CONVENORS Roger B.J. Benson, Richard J. Butler, Nadia B. Fröbisch, Hans C.E. Larsson, Mark A. Loewen, Philip D. Mannion, Jim I. Mead, Eric M. Roberts, Scott D. Sampson, Eric D. Scott, Kathleen Springer PROGRAM COMMITTEE Jonathan Bloch, Co-Chair; Anjali Goswami, Co-Chair; Jason Anderson; Paul Barrett; Brian Beatty; Kerin Claeson; Kristina Curry Rogers; Ted Daeschler; David Evans; David Fox; Nadia B. Fröbisch; Christian Kammerer; Johannes Müller; Emily Rayfield; William Sanders; Bruce Shockey; Mary Silcox; Michelle Stocker; Rebecca Terry November 2011—PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS 1 Members and Friends of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, The Host Committee cordially welcomes you to the 71st Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Las Vegas. -

Active Research Grants

Linda C. Ivany Professor Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences Heroy Geology Laboratory,Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY 13244 phone: (315) 443-3626 / fax: (315) 443-3363 / email: [email protected] http://thecollege.syr.edu/people/faculty/pages/ear/Ivany-Linda.html https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4692-3455 Education Ph.D. in Earth and Planetary Sciences, 1997, Harvard University Advisor: Stephen Jay Gould M.S. in Geology, minor in Zoology, 1990, University of Florida-Gainesville Advisor: Douglas S. Jones B.S. in Geology, minor in Zoology, 1988, Syracuse University Advisor: Cathryn R. Newton Academic Positions 2012-present Professor of Earth Sciences, Syracuse University 2005-2012 Associate Professor of Earth Sciences, Syracuse University 2001-2005 Assistant Professor of Earth Sciences, Syracuse University 2000-2001 Visiting Assistant Professor of Earth Sciences, Syracuse University 1997-2000 Michigan Society Fellow and Visiting Assistant Professor of Geological Sciences, University of Michigan General Research Interests Evolutionary Paleoecology, Paleoclimatology, Stable Isotopes in Paleobiology I am a marine paleoecologist and paleoclimatologist. My interests lie broadly in the evolution of the Earth-life system and how ecosystems and their component taxa evolve and respond to changes in the physical environment. Specific areas of interest include biotic and climatic change during the Paleogene (~65-24 million years ago); use of geochemical data, particularly stable isotopes, derived from accretionary biogenic materials for inference -

Paleontology and Stratigraphy of Eocene Rocks at Pulali Point, Jefferson County, Eastern Olympic Peninsula, Washington

PALEONTOLOGY AND STRATIGRAPHY OF EOCENE ROCKS AT PULALI POINT, JEFFERSON COUNTY, EASTERN OLYMPIC PENINSULA, WASHINGTON by RICHARD L. SQUIRES, JAMES L. GOEDERT, and KEITH L. KALER WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES REPORT OF INVESTIGATIONS 31 1992 ., WASHINGTON STATE DEPARTMENT OF Natural Resources Brian Boyle • Commhstoner of Public Lands An Steo_r0$ - Superv1sor Division ol Geology and Earth Resources Raymond Lcmnanls. State Geologlsl PALEONTOLOGY AND STRATIGRAPHY OF EOCENE ROCKS AT PULALI POINT, JEFFERSON COUNTY, EASTERN OLYMPIC PENINSULA, WASHINGTON by RICHARD L. SQUIRES, JAMES L. GOEDERT, AND KEITH L. KALER WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES REPORT OF INVESTIGATIONS 31 1992 W>.SHING'TON STAT1r OEPARTMDIT or Natural Resources 8ncll) Bov,. · COmmmioner ot Pu!xk: tancb M $i.atni; S\lp$1'WOJ' DtY!llcn 01 Gtology ahCS £artti ~ Raymond l.mlMn.:I ~Geologist Cover: From left, ?Falsifusus marysvillensis; Pachycrommium clarki; large bivalve, Veneri cardia hornii s.s.; Delectopecten cf. D. vancouverensis sanjuanensis; Turritella uvasana hendoni. These specimens are shown at 150 percent of the dimensions on Plates 1 and 3. Use of trade, product, or firm names in this report is for descriptive purposes only and does not consitute endorsement by the Washington Division of Geology and Earth Resources. This report is available from: Publications Washington Department of Natural Resources Division of Geology and Earth Resources P.O. Box 47007 Olympia, WA 98504-7007 Price $ 1.85 Tax (Stale residenl.t only) .15 Total $ 2.00 Mail orders must be prepaid; please add $1.00 to each order for postage and handling. Make checks payable to the Department of Natural Resources. -

PALEONTOLOGY Editor David S Berman Managing Editor Mary Ann Schmidt, ELS Coordinating Editors: International -

OFFICERS President - William A. Clemens, Jr. Vice President - David W. Krause Past President - C. S. Churcher Members-at-Large - Annalisa Berta OF Brent H. Breithaupt SOCIETY Kathleen M. Scott Secretary - John J. Flynn VERTEBRATE Treasurer - John R. Bolt NEWS BULLETIN EDITORS PALEONTOLOGY Editor David S Berman Managing Editor Mary Ann Schmidt, ELS Coordinating Editors: International - -. Miao Desui Canada Kevin Seymour Northeast USA Judy A. Massare Southeast Editor William P. Wall Midwest USA Russell W. Graham Rocky Mountain Region USA Brent H. Breithaupt Southwest USA Nicholas Czaplewski Pacific Coast USA George Callison Mexico Shelton P. Applegate COPY DEADLINES January 1, May 1, September 1 Send members' news to coordinating editors Send notices directly to Editor Published in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Subscription rate: $25.00 per year SOCIETY OF VERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY 401 N. Michigan Avenue Non-Protit Org. Chicago, IL 6061 1-4267 USA U.S. Postage Paid Pittsburgh, PA Pem~tNo. 307 I I 4 '. , r' ' NUMBER 163 JANUARY 1995 University of California - Berkeley 20874820 (JVP) 1734640X (NB) Main Library 01 - Periodicals NEWS BULLETIN Division BERKELEY CA 94720 USA It is extremely important to distinguish betwen archaeological and paleontological (=fossil) resource sites when defining the sensitivity of rock units. The boundaries of archaeological sites define the areal extent of the resource. Paleontologic sites, however, indicab that the containing sedimentary rock unit or formation is Conformable Impact Mitigation Guidelines Committee fossili8rous. The limik of the entire rock formation, both areal and stratigraphic, therefore detine the scope of The Committee for Conformable Impact Mitigation Guidelines has been active for five the paleontologic potential in each case. -

Geologic, Climatic, and Vegetation History of California

GEOLOGIC, CLIMATIC, AND VEGETATION HISTORY OF CALIFORNIA Constance I. Millar I ntroduction The dawning of the “Anthropocene,” the era of human-induced climate change, exposes what paleoscientists have documented for decades: earth’s environment—land, sea, air, and the organisms that inhabit these—is in a state of continual flux. Change is part of global reality, as is the relatively new and disruptive role humans superimpose on environmental and climatic flux. Historic dynamism is central to understanding how plant lineages exist in the present—their journey through time illuminates plant ecology and diversity, niche preferences, range distributions, and life-history characteristics, and is essential grounding for successful conservation planning. The editors of the current Manual recognize that the geologic, climatic, and vegetation history of California belong together as a single story, reflecting their interweaving nature. Advances in the sci- ences of geology, climatology, and paleobotany have shaken earlier interpretations of earth’s history and promoted integrated understanding of the origins of land, climate, and biota of western North America. In unraveling mysteries about the “what, where, and when” of California history, the respec- tive sciences have also clarified the “how” of processes responsible for geologic, climatic, and vegeta- tion change. This narrative of California’s prehistory emphasizes process and scale while also portraying pic- tures of the past. The goal is to foster a deeper understanding of landscape dynamics of California that will help toward preparing for changes coming in the future. This in turn will inform meaningful and effective conservation decisions to protect the remarkable diversity of rock, sky, and life that is our California heritage. -

Clear Felling Atop Aucklands Highest Peak: the Destruction of Submontane Shrubland on Kohukohunui Hunua Range T

Autumn is a time for fruiting of the shrubs and many Botanical Gardens). colourful red or orange fruits were evident especially Other particularly prominent families are Asteraceae on Berberis Cotoneaster Rosa and Lonicera Rosaceae and Fabaceae. Artemisia is exceptionally ManyGentianaceae were in flower and two species of common on the Loess Plateau and in ruderal great beauty were Swertia dichotoma and Gentianavegetation . There are dozens of species all of which lawrencei var. farreri. Gentianceae is an important are highly aromatic (wormwood or sagebush). family here (Comastoma Gentiana Gentianopsis Potentilla abounds with shrubby as well as creeping Ha Ien ia Lomatogonium Swertia) and I met Dr Chen herbaceous species (e.g. P. anserina) in the steppe Shilong of the Northwest Plateau Institute of Biology and meadow vegetation. Of the legumes Astragalus who with his colleagues is "doing" the Gentianaceae Caragana Hedysarum Oxytropis and Thermopsis for the new Flora of China series in English (Missouri widely occur. Acknowledgements Plants were identified with the help of three local experts Wei Zhengduo retired Qinghai Forestry Bureau engineer; Lu Xuefeng Northwest Plateau Institute of Biology; and Zhang Zhihe retired Grassland Institute scientist. I sincerely thank Marta Treskonova for her ecological observations in the field. References Liu Shangwu (Chief ed.) 1999: Flora Qinghalca. 4 volumes. Qinghai Peoples Publishing House Xining. Ren Jizhou; Zhu Tingcheng; Guo Benzhao (advisors); Cai Zhaoguang; Lan Baining; Lei Gengxing (compilers) 1986: An atlas of rangeland and its main plant resources on the Qi nghai Tibet Plateau. Volume: Qinghai. Agricultural Publishing House Xining. Wu Yuhu; Mei Lijuan (eds.) 2001: The plant resources in the source area of the Yellow River and its environment.