Financial Services Sector Assessment on Vanuatu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pol I T Ical Reviews • Melanesia 467 References Vanuatu

pol i t ical reviews • melanesia 467 References controlling prisoners. Issues of eco- nomic policy also created challenges Fraenkel, Jonathan, Anthony Reagan, and with Vanuatu’s financial services David Hegarty. 2008. The Dangers of sector coming under increasing pres- Political Party Strengthening Legislation in Solomon Islands. State Society and Society sure, the rising cost of living being felt in Melanesia Working Paper (ssgm) quite strongly, and a proposed increase 2008/2. Canberra: ssgm, The Australian to employment conditions creating National University. uncertainty within the private sector. Ham Lini’s National United Party ISN, Island Sun News. Daily newspaper, Honiara. (nup)–led coalition had taken over in December 2004, following a success- mehrd, Ministry of Education and ful vote of no confidence against the Human Resources Development. 2009. government coalition led by Serge Semi-annual Report, January–July. Vohor’s Union of Moderate Parties mehrd: Honiara. (ump), which had been elected only NEN, National Express News. Tri-weekly five months earlier. Although several newspaper, Honiara. reshuffles took place in the intervening sibc, Solomon Islands Broadcasting years, Lini’s ability to survive to the Corporation. Daily Internet news service, end of Parliament’s four-year term was Honiara. http://www.sibconline.com remarkable. The previous decade had SSN, Solomon Star News. Daily news - seen regular votes of no confidence paper, Honiara. Online at and numerous threats of such votes http://solomonstarnews.com / leading to nine different coalition sto, Solomon Times Online. Daily governments and two snap elections. Internet news service, Honiara. Lini was able to stay in power mainly http://www.solomontimes.com because he refused to take action (ie, hold accountable politicians who were members of the coalition accused of mismanagement, corruption, or misbehavior) or make decisions that Vanuatu could jeopardize the coalition. -

52031-001: Port Vila Integrated Urban Improvements Project

Resettlement Plan Project No.: 52031-001 Status: Final Draft Date: October 2020 VAN: Greater Port Vila Urban Resilience Project Prepared by the Ministry of Internal Affairs for the Asian Development Bank. This Resettlement Plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank CBD - central business district CCP - Communications and consultation plan (for the Project) CEMP - Construction environmental management plan (of the contractor) CSS - country safeguards system DEPC - Department of Environmental Protection and Conservation DLA - Department of Local Authorities (within MoIA) DSC - Design and supervision consultant ECPA - Environmental Protection and Conservation Act EIA - environmental impact assessment EIS - environmental impact statement EMP - environmental management plan EPCA - Environment Protection and Conservation Act 2010 GPV - Greater Port Vila GPVURP Greater Port Vila Urban Resilience Project GRM - grievance redress mechanism IEE - initial environmental examination MCC - Ministry of Climate -

Vanuatu C I T I Z E N S H I P P R O G R a M

VANUATU C I T I Z E N S H I P P R O G R A M WHAT IS VANUATU FAMOUS FOR? Vanuatu is famous for spectacular coral reefs and canyons take a backseat in Vanuatu, where WWII left a lasting legacy of shipwrecks. The Island of Santos is famous for Known for its phenomenal diving and snorkelling, turquoise freshwater blue holes, famous white beaches and caves to enjoy nature and pristine beauty. Efate island offers lot of adventure activities. Besides this, more than 100 languages are found in Vanuatu. DO YOU KNOW? I T T A K E S 1 0 Y E A R S O F L I V I N G T O N A T U R A L I Z E F O R V A N U A T U C I T I Z E N S H I P V A N A U T U C I T I Z E N S H I P I S H A R D E S T T O G E T I N T H E W O R L D V A N U A T U O F F E R S C I T I Z E N S H I P F O R I N V E S T M E N T S IN JUST 30 DAYS You dont have to WAIT for 10 years to become a Vanuatu citizen C I T I Z E N S H I P B Y I N V E S T M E N T HOW TO GET VANUATU CITIZENSHIP Development Support and Contribution Program Fastest CIP in the World Vanuatu becomes the most popular CIP in 2020 The Citizenship process for Vanuatu DSP is pretty straightforward. -

Economic Impacts of Natural Hazards on Vulnerable Populations in VANUATU Contents

Economic Impacts of Natural Hazards on Vulnerable Populations in VANUATU Contents List of abbreviations ii Executive summary 1 Hazard and exposure 2 1 1.1. Overview of risks 2 1.2. Cyclones 5 1.3. Earthquakes and tsunamis 7 1.4. Volcanoes 7 1.5. Droughts 8 Vulnerability and impacts 9 2 2.1. Economic profile 9 2.2. Agriculture and fisheries 10 2.3. Tourism 11 2.4. Commerce and industry 12 2.5. Housing and settlements 12 2.6. Low-income and informal workers 13 2.7. Gender 15 2.8. Youth 19 Coping mechanisms 22 3 3.1. Types of coping mechanisms 22 3.2. Adaptive social protection 22 3.3. Remittances 24 3.4. Financial inclusion 26 3.5. Insurance 27 3.6. Migration and relocation 28 3.7. Community-based support 30 Conclusions 32 4 4.1. Hazard, exposure, and vulnerability 32 4.2. Coping mechanisms 33 References 36 i List of abbreviations ADB Asian Development Bank CRED Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters CSIRO Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation EM-DAT Emergency Events Database ESCAP Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific GDP Gross Domestic Product GFDRR Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery GIZ Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit IASC Inter-Agency Standing Committee Reference Group on Risk, Early Warning and Preparedness IDMC Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre IFRC International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies ILO International Labour Organization IMF International Monetary Fund INFORM Index for Risk Management MSME Micro-, small-, -

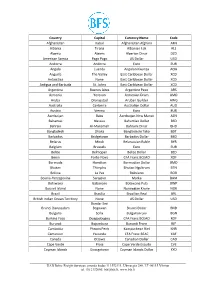

International Currency Codes

Country Capital Currency Name Code Afghanistan Kabul Afghanistan Afghani AFN Albania Tirana Albanian Lek ALL Algeria Algiers Algerian Dinar DZD American Samoa Pago Pago US Dollar USD Andorra Andorra Euro EUR Angola Luanda Angolan Kwanza AOA Anguilla The Valley East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antarctica None East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda St. Johns East Caribbean Dollar XCD Argentina Buenos Aires Argentine Peso ARS Armenia Yerevan Armenian Dram AMD Aruba Oranjestad Aruban Guilder AWG Australia Canberra Australian Dollar AUD Austria Vienna Euro EUR Azerbaijan Baku Azerbaijan New Manat AZN Bahamas Nassau Bahamian Dollar BSD Bahrain Al-Manamah Bahraini Dinar BHD Bangladesh Dhaka Bangladeshi Taka BDT Barbados Bridgetown Barbados Dollar BBD Belarus Minsk Belarussian Ruble BYR Belgium Brussels Euro EUR Belize Belmopan Belize Dollar BZD Benin Porto-Novo CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Bermuda Hamilton Bermudian Dollar BMD Bhutan Thimphu Bhutan Ngultrum BTN Bolivia La Paz Boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Sarajevo Marka BAM Botswana Gaborone Botswana Pula BWP Bouvet Island None Norwegian Krone NOK Brazil Brasilia Brazilian Real BRL British Indian Ocean Territory None US Dollar USD Bandar Seri Brunei Darussalam Begawan Brunei Dollar BND Bulgaria Sofia Bulgarian Lev BGN Burkina Faso Ouagadougou CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Burundi Bujumbura Burundi Franc BIF Cambodia Phnom Penh Kampuchean Riel KHR Cameroon Yaounde CFA Franc BEAC XAF Canada Ottawa Canadian Dollar CAD Cape Verde Praia Cape Verde Escudo CVE Cayman Islands Georgetown Cayman Islands Dollar KYD _____________________________________________________________________________________________ -

The Performance of Melanesian Central Banks

The Performance of Melanesian Central89 Banks 89 Journal of Central Banking Theory and Practice, 2013, 1, pp. 89-110 UDC: 336.711(595) Received: 10 September 2012; accepted: 9 October 2012. Michael Turner* & Alistair Brown** * Lecturer Financial Accounting, School of Accounting, Curtin The Performance of Melanesian University, Western Australia Central Banks E-mail: [email protected] ** Professor, School of Abstract: Since independence, the Melanesian central banks of the Accounting, Curtin Reserve Bank of Fiji, Bank of Papua New Guinea, Central Bank of University, Western Solomon Islands and Reserve Bank of Vanuatu have operated au- Australia tonomously in their respective domestic economies through trouble- some times. In one form or another, they have had to endure inter- E-mail: [email protected] national condemnation, coups, corruption and crises. Using classic modernization theory and combination reporting analysis, this pa- per considers possible operational central bank efficiencies from the construction of a joint Melanesian central bank. Annual reports for the year ending 2008 from the cities of Suva, Port Moresby, Honiara and Port Vila were gathered to conduct textual analysis of the an- nual reporting of the Melanesian central banks, both individually and collectively through combination reporting analysis. The results of the analysis of the performance of the individual Melanesian cen- tral banks identify huge net losses resulting from speculative foreign currency trading, substantial risks from holding extensive foreign assets, and worrying governance issues through unusual dividend practices and balance sheet reserve manipulation. In light of the results, there appears a case for using combination reporting as an instrument for examining potential performance of emerging cen- tral bank problems and for considering a united Melanesian central bank to help rectify some of these problems. -

Healthy Islands: Best Practices in Health Promotion in the Pacific

Healthy Islands: Best Practices in Health Promotion in the Pacific Healthy Islands: Best Practices in Health Promotion in the Pacific a a Healthy Islands: Best Practices in Health Promotion in the Pacific © World Health Organization 2017 ISBN-13 978 92 9061 827 0 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization (http://www.wipo.int/amc/en/mediation/rules). Suggested citation. Healthy islands: best practices in health promotion in the Pacific. 2017. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) data. -

Pacific Economic Monitor – December 2019

Pacific Economic Monitor December 2019 www.adb.org/pacmonitor The Monitor provides an update of developments in Pacific economies and DEVELOPMENT CHALLENGES IN explores topical policy issues. SMALL ISLAND DEVELOPING STATES of ADB's developing member Contents countries classified as SIDS are in the Pacifica Highlights 1 of the Pacific SIDS are further International and regional developments 3 classified as fragile and conflict-aected Country economic issues 5 situations (FCAS), reflecting thin capacities for public service delivery Policy briefs: and broader governance Addressing the needs of small island developing states . FCAS cuto score (on a scale of 24 to ) in ADB's country performance Mapping fragility in the Pacific 28 assessments Atoll nations: Key takeaways from the frontlines of climate change 34 Poverty reduction challenges: Insights from Papua New Guinea 36 Elevated cost structures: Heightened Economic indicators 40 High costs of living and vulnerability: service delivery wipe out per On a scale of to , capita incomes that are SIDS average . nominally high in most SIDS on the United Nations’ Economic Vulnerability % lower average per capita incomes for the Index, almost double SIDS vs. non-SIDS that for non-SIDS (.) ADB developing member Highlights countries (adjusted for y Trade conflict continues to weigh down purchasing power parity) on the global economy. Prospects for global growth continue to weaken as the ongoing trade conflict slows growth in major economies, including the People’s Republic of China. The weak external environment translates into a softer 2019–2020 outlook for the Pacific through subdued exports, Key elements of a dierentiated approach to SIDS: including from Fiji. -

National Fishery Sector Overview Vanuatu

FISHERY AND AQUACULTURE Food and Agriculture FID/CP/VUT COUNTRY PROFILE Organization of the United Nations PROFIL DE LA PÊCHE ET DE Organisation des Nations Unies L’AQUACULTURE PAR PAYS pour l'alimentation et l'agriculture May 2010 RESUMEN INFORMATIVO SOBRE Organización de las Naciones LA PESCA Y LA ACUICULTURA POR Unidas para la Agricultura y la PAÍSES Alimentación NATIONAL FISHERY SECTOR OVERVIEW VANUATU 1. GENERAL GEOGRAPHIC AND ECONOMIC DATA Area: 12 190 km² Water area: 680 000 km² Shelf area: [no continental shelf] Length of continental coastline: 1 920 km (length of the coast of islands) Population (2007): 228 000 GDP at purchaser's value (2007) 512 977 000 USD1 GDP per head (2007): 2 242 USD Agricultural GDP (2007): 73 818 000 USD2 Fisheries GDP (2007): 3 883 000 USD3 2. FISHERIES DATA Total Per Caput 2007 Production Imports Exports Supply Supply tonnes liveweight kg/year Fish for direct human 78 187 3 035 73 565 7 657 33.6 consumption4 Fish for animal 7 200 --- --- --- --- 1 2007 average exchange rate: US$1 = Vanuatu vatu 104.0; GDP source: unpublished data kindly provided by the Vanuatu National Statistics Office 2 This is the contribution of “total agriculture” in an unpublished document kindly provided by the Vanuatu National Statistics Office. “Total agriculture” includes commercial and subsistence fishing. 3 This is the official fishing contribution to GDP. A recalculation shows the total fishing contribution to be USD$6.7 million: Gillett (2009). The Contribution of Fisheries to the Economies of Pacific Island Countries and Territories. Pacific Studies Series, Asian Development Bank, Manila 4 Data from FAO food balance sheet of fish and fishery products. -

12082038 01.Pdf

MINISTRY OF FINANCE AND ECONOMIC MANAGEMENT MINISTRY OF INFRASTRUCTURE AND PUBLIC UTILITIES THE REPUBLIC OF VANUATU PREPARATORY STUDY FOR THE PROJECT ON INTERNATIONAL MULTI MODAL PORT AT STAR WHARF IN PORT VILA IN THE REPUBLIC OF VANUATU (ENVIRONMENTAL STUDY) FINAL REPORT JANUARY 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY IDEA CONSULTANTS, INC. IDES INC. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (AS OF JANUARY 2012) 1 Vanuatu Vatu = 0.84 Japanese Yen Efate Island Location of Efate Island, Republic of Vanuatu Port Vila Port Vila Bay Location of Port Vila N Vatumaru Bay Port Vila Bay Iririki I. Paray Bay Pontoon Bay Main Wharf Star Wharf 0 500 1000 Meters Study Area Star Wharf Overlay of the Chart of Port Vila on IKONOS Satellite Image Dredging Reclamation Pier Existing Yard Existing Wharf Container Yard Layout Plan of Star Wharf Summary 1. OUTLINE OF THE STUDY 1.1 Study Objectives Although EIA of Star Terminal Development had been prepared in the feasibility study by AusAID and the report had been approved by the Department of Environment of the Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources of the Government of Vanuatu in August 2010, JICA Fact Finding Survey Team, in response to the financing request by Government of Vanuatu, surveyed the project area and concluded that further data collection was needed to upgrade the impact assessment on coral reef ecosystems and water current of Port Vila Bay. Under those circumstances, this study was conducted aiming to collect supplemental data on coral reef conditions and water current of the bay as well as to develop mitigation measures and monitoring plans after the construction work in order to realize the project with the loan assistance by the Government of Japan. -

Currencies Operating Under New Wire Payment Process

Currencies currently operating under the new wire payment process Curr en cy Bank Name Africa Code Kenyan Shilling KES Stanbic Bank, Nairobi Namibian Dollar NAD Standard Bank Namibia, Ltd, Windhoek South African Rand ZAR Standard Bank of South Africa, Johannesburg Curr en cy Bank Name Asia Code Hong Kong Dollar HKD Standard Chartered Bank, Hong Kong Indian Rupee** INR ICICI Bank, Local Western Union Agent Locations Japanese Yen JPY Standard Chartered Bank, Tokyo Singapore Dollar SGD The Bank of New York Mellon Thai Bhat THB HSBC Bank, Bangkok Curr en cy Australia / Oceania Code Bank Name Australian Dollar AUD HSBC Bank, Sydney Fiji Dollar FJD Westpac Banking Corporation, Suva New Zealand Dollar NZD Westpac Banking Corporation, Wellington Samoan Tala WST Westpac Bank Samoa Limited, Apia Tahitian (Central Polynesian) Franc XPF Banque de Polynesie, Papeete Vanuatu Vatu VUV Westpac Banking Corporation, Port Vila Curr en cy Bank Name Europe Code British Pound GBP HSBC Bank PLC, London Czech Republic Koruna CZK Ceskoslovenska Obchodni Banka Danish Krone DKK Danske Bank, Copenhagen Euro (Main)*** EUR HSBC Bank PLC, London Hungarian Forint HUF HSBC Bank PLC, London Latvian Lats LVL HSBC Bank PLC, London Lithuanian Litas LTL HSBC Bank PLC, London Norwegian Krone NOK Den Norske Bank, Oslo Polish Zloty PLN ING Bank, Poland Swedish Krona SEK Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken (SEB), Stockholm Swiss Fran c CHF Credit Suisse, Zurich Curr en cy Bank Name Middle East Code Bahrain Dinar BHD HSBC Bank PLC, London Israeli Shekel ILS HSBC Bank PLC, London Jordanian JOD HSBC Bank PLC, London Dinar Kuwaiti KWD HSBC Bank PLC, London Dinar Omani OMR HSBC Bank PLC, London Rial Qatari Rial QAR HSBC Bank PLC, London Turkish Lira TRY HSBC Bank PLC, London United Arab Emirates Dirham AED HSBC Bank PLC, London Curr en cy Bank Name North America Code Canadian Dollar CAD Royal Bank of Canada, Montreal Mexican Peso MXN HSBC Bank, Mexico United States Dollar (Main) USD Bank of New York Mellon, New York * Students in the Guangdong Province can utlize CITIC Bank in person. -

Vanuatu Services Sector Analysis

VANUATU SERVICES SECTOR ANALYSIS Vanuatu Snapshot Capital: Port Vila Population: 245,619 (WB 2011) Currency: Vanuatu Vatu GDP (constant 2000 US$): 367,897,412.7 (WB 2011) GDP per capita: $3866.6 at PPP (WB 2011) GDP Growth: 1.4% (WB 2011) External Debt: 25.3% of GNI (WB 2011) Ease of Doing Business: 80/185 (WB 2012) Corruption Index: 73/176 (TI, 2012) 1. Overview of the Vanuatu Economy This South Pacific island economy is based on the primary sectors agriculture, forestry and fishing, which provide a living for the majority of Vanuatu's population. Offshore financial services and tourism are other mainstays of the economy. The development of Vanuatu is constrained by its relatively narrow export base. Services, in particular tourism, account for 40% of the GDP and represent the most important source of income, together with real estate and wholesale and retail trade. Much of the growth in recent years has been driven by these sectors. Vanuatu heavily invests in social services, especially education. Mineral deposits are negligible. A small light industry sector caters to the local market. Tax revenues come mainly from import duties. Economic development is also hindered by the vulnerability to natural disasters, and long distances from main markets and between constituent islands. In response to foreign concerns, the government has promised to tighten regulation of its offshore financial center. In mid-2002, the government stepped up efforts to boost tourism through improved air connections, resort development, and cruise ship facilities. Australia and New Zealand are the main suppliers of tourists and foreign aid.