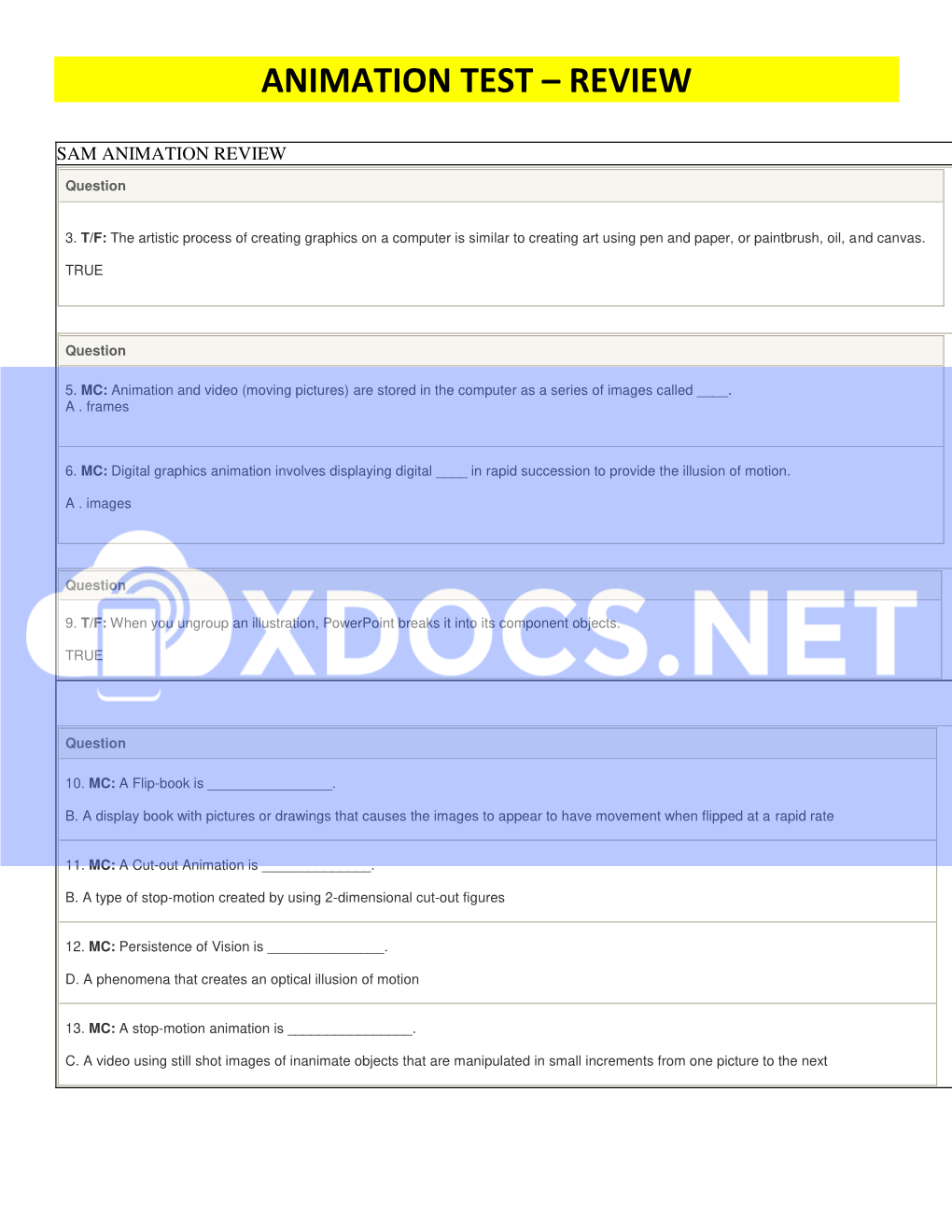

Animation Test – Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animation 1 Animation

Animation 1 Animation The bouncing ball animation (below) consists of these six frames. This animation moves at 10 frames per second. Animation is the rapid display of a sequence of static images and/or objects to create an illusion of movement. The most common method of presenting animation is as a motion picture or video program, although there are other methods. This type of presentation is usually accomplished with a camera and a projector or a computer viewing screen which can rapidly cycle through images in a sequence. Animation can be made with either hand rendered art, computer generated imagery, or three-dimensional objects, e.g., puppets or clay figures, or a combination of techniques. The position of each object in any particular image relates to the position of that object in the previous and following images so that the objects each appear to fluidly move independently of one another. The viewing device displays these images in rapid succession, usually 24, 25, or 30 frames per second. Etymology From Latin animātiō, "the act of bringing to life"; from animō ("to animate" or "give life to") and -ātiō ("the act of").[citation needed] History Early examples of attempts to capture the phenomenon of motion drawing can be found in paleolithic cave paintings, where animals are depicted with multiple legs in superimposed positions, clearly attempting Five images sequence from a vase found in Iran to convey the perception of motion. A 5,000 year old earthen bowl found in Iran in Shahr-i Sokhta has five images of a goat painted along the sides. -

The Walt Disney Silly Symphony Cartoons and American Animation in the 1930S

Exploration in Imagination: The Walt Disney Silly Symphony Cartoons and American Animation in the 1930s By Kendall Wagner In the 1930s, Americans experienced major changes in their lifestyles when the Great Depression took hold. A feeling of malaise gripped the country, as unemployment rose, and money became scarce. However, despite the economic situation, movie attendance remained strong during the decade.1 Americans attended films to escape from their everyday lives. While many notable live-action feature-length films like The Public Enemy (1931) and It Happened One Night (1934) delighted Depression-era audiences, animated cartoon shorts also grew in popularity. The most important contributor to the evolution of animated cartoons in this era was Walt Disney, who innovated and perfected ideas that drastically changed cartoon production.2 Disney expanded on the simple gag-based cartoon by implementing film technologies like synchronized sound and music, full-spectrum color, and the multiplane camera. With his contributions, cartoons sharply advanced in maturity and professionalism. The ultimate proof came with the release of 1937’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, the culmination of the technical and talent development that had taken place at the studio. The massive success of Snow White showed that animation could not only hold feature-length attention but tell a captivating story backed by impressive imagery that could rival any live-action film. However, it would take nearly a decade of experimentation at the Disney Studios before a project of this size and scope could be feasibly produced. While Mickey Mouse is often solely associated with 1930s-era Disney animation, many are unaware that alongside Mickey, ran another popular series of shorts, the Silly Symphony cartoons. -

Employment, Autonomy and Alienation in US Film Animation

Western University Scholarship@Western FIMS Publications Information & Media Studies (FIMS) Faculty 7-22-2010 Cultural Labor’s “Democratic Deficits”: Employment, Autonomy and Alienation in US Film Animation Matt Stahl The University of Western Ontario Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/fimspub Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Citation of this paper: Stahl, Matt, "Cultural Labor’s “Democratic Deficits”: Employment, Autonomy and Alienation in US Film Animation" (2010). FIMS Publications. 333. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/fimspub/333 RCUV_A_479671.fm Page 271 Saturday, April 17, 2010 12:41 PM JOURNAL FOR CULTURAL RESEARCH VOLUME 14 NUMBER 3 (JULY 2010) Cultural Labor’s “Democratic Deficits”: Employment, Autonomy and Alienation in US 5 Film Animation Matt Stahl TaylorRCUV_A_479671.sgm10.1080/14797581003791495Journal1479-7585Original20101430000002010MattStahlmstahl@uwo.ca and& for Article Francis (print)/1740-1666FrancisCultural Research (online) 10 Cultural industries’ reliance on streams of novel cultural material requires grant- ing creative employees significant degrees of autonomy within firms. In Bill 15 Ryan’s formulation, “capitalists cannot manage artists like they can other cate- AQ1 gories of worker” (1992, p. 34). This article expands on these findings by focusing on key moments in the early history of cinematic animation and aspects of contemporary animation production. Drawing on political-theoretical analyses of employment to limn substantive limits to the autonomy of artists integrated into Hollywood production, it shows that the institution of employment enables 20 cultural industry employers not only to dispossess artists of their creative work(s), but also, when they deem it expedient, to manage artists like other kinds of workers. -

And in Computer Animation?

Computer Animation 0-Introduction SS 15 Prof. Dr. Charles A. Wüthrich, Fakultät Medien, Medieninformatik Bauhaus-Universität Weimar caw AT medien.uni-weimar.de Overview • Specifying motion [5 W] • Passive motion (physics-based and – History of animation, computer procedural methods) [4 W] animation – Particle systems – Review splines – Rigid bodies – Keyframing parameterized – Contact and collision models – Mass-spring systems – Freeform deformations – Noise and turbulence – Morphing • Active motion (controller and data- driven methods) [3 W] – Review quaternions – Flocking behaviour – Rigid bodies – Motion optimization – Inverse kinematics – Motion capture – Character skinning • 2D motion [2 W] – Interpolated motion Aim of the course • To present techniques used in animations, i.e. “moving objects” – Algorithms – Mathematical methods – Movement studies – Not for the faint of heart – Lots of math, but also fun Exercitations • Final grades • 40% exercitations • 60% final exam. • Exercitations: – Aline.Helmke[at]uni-weimar.de and Bernhard.Bittorf[at]uni-weimar.de April 15 Charles A. Wüthrich 4 Literature • Rick Parent: „Computer Animation. Algorithms and Techniques“, Morgan Kaufman 2002 • http://www.blender.org • http://www.uni-weimar.de/medien/cg Computer Animation 1-History SS 13 Prof. Dr. Charles A. Wüthrich, Fakultät Medien, Medieninformatik Bauhaus-Universität Weimar caw AT medien.uni-weimar.de Early animation devices • First experiments with persistence of vision done early 1800 • Animation existed before the camera • Perhaps simplest device: thaumatrope – Flipping circle with two drawings Charles A. Wüthrich Early animation devices • Flipbook – Very common, and survived till today • Motion through page flipping Charles A. Wüthrich Early animation devices • Zoetrope: wheel of light • Cylinder – Inside: drawings – Slits cut between frames on cylinder – Allow viewer to see only one frame – Illusion of movement Charles A. -

Animated Television: the Narrative Cartoon” Was Originally Published in the Third Edition of Jeremy G

“Animated Television: The Narrative Cartoon” was originally published in the third edition of Jeremy G. Butler, Television: Critical Methods and Applications (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 2007), 325-361. It was not included in subsequent editions of Television and consequently it was placed online, although not in the public domain. All © copyrights are still reserved. If citing this chapter, please use the original publication information (above). Questions? Contact Jeremy Butler at [email protected] or via TVCrit.com. ch11_8050_Butler_LEA 8/11/06 8:46 PM Page 325 CHAPTER 11 Animated Television: The Narrative Cartoon Beginnings The Aesthetics of the 1930s Sound Cartoon: Disney’s Domination UPA Abstraction: The Challenge to Disney Naturalism Television’s Arrival: Economic Realignment TV Cartooning Since the 1980s Summary edition FurtherTELEVISION Readings 3rd nimation has had a rather erratic presence on television. A A mainstay of Saturday morning children’s programming, small snippets of it appear regularly in commercials,TVCrit.com credit sequences, music videos, news and sports, but there have been long stretches when there were no prime-time cartoon shows. After The Flintstones ended its original run in 1966 there wasn’t another successful prime-time show until 23 years later, when The Simpsons debuted. Since 1989 there has been something of a Renaissance in television animation. Numerous prime-time cartoon pro- grams have appeared and at least three cable channels have arisen that fea- ture cartoons—the Cartoon Network, Nickleodeon, and Toon Disney. And, of course, cartoons continue to dominate the TV ghettos of Saturday morn- ing and weekday afternoons. Although numerous new animated programs are now being created, many of the cartoons regularly telecast today were produced fifty, sixty, or even seventy years ago. -

Animation Fandom in North America and East Asia from 1906–2010 By

Animating Transcultural Communities: Animation Fandom in North America and East Asia from 1906–2010 By Sandra Annett A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of English, Film, and Theatre University of Manitoba Winnipeg © 2011 Sandra Annett Abstract This dissertation examines the role that animation plays in the formation of transcultural fan communities. A ―transcultural fan community‖ is defined as a group in which members from many national, cultural, and ethnic backgrounds find a sense of connection across difference, engaging with each other through a mutual interest in animation while negotiating the frictions that result from their differing social and historical contexts. The transcultural model acts as an intervention into polarized academic discourses on media globalization which frame animation as either structural neo-imperial domination or as a wellspring of active, resistant readings. Rather than focusing on top-down oppression or bottom-up resistance, this dissertation demonstrates that it is in the intersections and conflicts between different uses of texts that transcultural fan communities are born. The methodologies of this dissertations are drawn from film/media studies, cultural studies, and ethnography. The first two parts employ textual close reading and historical research to show how film animation in the early twentieth century (mainly works by the Fleischer Brothers, Ōfuji Noburō, Walt Disney, and Seo Mitsuyo) and television animation in the late twentieth century (such as The Jetsons, Astro Boy and Cowboy Bebop) depicted and generated nationally and ethnically diverse audiences. -

Capa Até Sumario

UNIVERSIDADE PRESBITERIANA MACKENZIE ! THAIS FERNANDA MARTINS HAYEK ! ! ! ! ! ENTRE O NOVO E O ATEMPORAL: A SONORIDADE PLÁSTICA DE FANTASIA ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! SÃO PAULO 2014 ! "1 THAIS FERNANDA MARTINS HAYEK ! ! ! ! ENTRE O NOVO E O ATEMPORAL: A SONORIDADE PLÁSTICA DE FANTASIA ! ! ! ! Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós graduação em Educação, Arte e História da Cultura, da Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie, como requisito parcial á obtenção do título de doutor em Educação, Arte e História da Cultura. ! Profª. Drª. Regina Célia Faria Amaro Giora ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! SÃO PAULO 2014 ! "2 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! !H417e Hayek, Thais Fernanda Martins. ! Entre o novo e o atemporal : a sonoridade plástica de Fantasia / ! Thais Fernanda Martins Hayek. – 2014. !! 216 f. : il. ; 30 cm. Tese (Doutorado em Educação, Arte e História da Cultura) - ! Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie, São Paulo, 2014. !! Referências bibliográficas: f. 205-215. 1. Animação. 2. Música. 3. Fantasia. 4. Disney, Walt, ! 1901-1966. 5. Arquétipos. 6.! Mitos. I. Título. THAIS FERNANDA MARTINS HAYEKCDD 791.436 ! "3 ENTRE O NOVO E O ATEMPORAL: A SONORIDADE PLÁSTICA DE FANTASIA ! Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós graduação em Educação, Arte e História da Cultura, da Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie, como requisito parcial á obtenção do título de doutor em Educação, Arte e História da Cultura. ! Aprovada em: ! BANCA EXAMINADORA __________________________________________ Prof. Drª Regina Célia Faria Amaro Giora – orientadora _________________________________________________________ -

John Randolph Bray, the Motion Picture Pioneer Who Transformed Animation from A

NO. 69 FOB "he Museum of Modern Art IMMEDIATE RELEASE [1 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modernart FATHER OF ANIMATION TO BE HONORED BY MUSEUM ON 96th BIRTHDAY John Randolph Bray, the motion picture pioneer who transformed animation from a crude experiment into an art and an industry, will be honored by The Museum of Modern Art on his 96th birthday, August 25, 1975. Two different programs of his cartoons will be shown, at 2-.00 and 5:30, and Bray will attend the earlier showing to introduce the program. The two programs will be shown again on Sunday, August 31, at 12:30 and 3:00. Born in Addison, Michigan, in 1879, John Randolph Bray began his career in 1900 as a staff artist for the Detroit Evening News. In 1910 he started working seriously on a method of producing motion picture cartoons efficiently, and his "The Daschund and the Sausage" (1910) was the first animated film made with the cell process. This process, which he later patented, put the stationary elements of the cartoon frame on a translucent sheet which was placed over each drawing of the moving elements. This eliminated the need to redraw the static parts of each frame, a process so tedious it had effectively prevented animation from developing. By 1913, Bray was releasing cartoons through The Pathe Exchange, and he began his first series, featuring Colonel Heeza Liar, the same year. In 1914, he organized the second animation studio in existence and took out the first of his many patents. -

Funny Stuff: Silent Comedies and Cartoons

Funny Stuff Silent Comedies and Cartoons Saturday, July 16, 2011 Grand Ilusion Cinema The Sprocket Society Seattle, WA About Two-Reeler Comedies In the 20 years before 1914, shorts were the show. And even decades after the feature film came along, shorts were a standard – and expected – part of every movie screening. At first movies were limited to the very short lengths of film that would fit in the camera, less than 1 or 2 minutes. Folks quickly figured out you could glue different shots together, and that you could then string those along to tell a longer story. But it would be some years before movies became more than a series of theatrically-staged tableaux and slice-of-life “actualities,” all filmed proscenium style. In the earliest days, exhibitors bought film prints outright and would craft programs from them. They’d often go on the road, touring their movie shows with accompanying lectures and music. There were even traveling tent shows. Soon the vaudeville houses also started showing shorts, which fit perfectly into their variety programming format. By 1905, the Nickelodeon era was in full swing in the US, made possible by moving to a rental distribution model instead of outright sales. Thousands of storefront screening rooms proliferated like mayflies all over the country, and in some cities they lined both sides of whole blocks. Your nickel got you about 30 minutes of mixed reels, with a new show usually every day. Folks would often go from one theater to another, right down the row. The profit was made in the high turnover, and audiences loved it. -

History of Animation & Animation

History of Animation & Animation Art In 1999, Michael Crandol entered this essay into a contest sponsored by Joe & Vicki Tracy's Animation History Website where he won first place and a limited edition signed copy of The Illusion of Life. 6 years on, this essay is just as fabulous and still has the same impact. If you haven’t read it before, you’re in for a treat. Enjoy! From the beginning, animation has been an important part of film history. Even before the invention of the motion picture camera, photographer Eadweard Muybridge used sequential photographs to analyze animal and human movement. Early 19th-century devices such as the thaumatrope, praxinoscope and zoetrope anticipated motion picture animation by making still images appear to move. Quickly flashing a series of still pictures past the viewer, these devices took advantage of a phenomenon called "persistence of vision." Because the human eye briefly retains an impression of an image after it has disappeared, the brain will read a rapid series of images as an unbroken movement. Animated films work on the same principle. Each frame of an animated film is a separate still picture, individually exposed. Drawings or props are moved slightly between exposures, creating an illusion of movement when the film is projected. In 1892, Emile Reynaud opened his popular Théâtre Optique in Paris, where he projected films that had been drawn directly on transparent celluloid, a technique that would not be used again until the 1930s. The ‘trick-films’ of Parisian magician Georges Méliès mixed stop-motion and single-frame photography with live-action film for magical effect. -

Conference Paper (SLIDE – WALT DISNEY) Americans in the 1930S Experienced Major Changes in Their Lifestyles When the Great

Conference Paper (SLIDE – WALT DISNEY) Americans in the 1930s experienced major changes in their lifestyles when the Great Depression took hold. Despite the economic situation, movie attendance remained strong during the decade.1 Americans attended films as a way to escape from their everyday lives. While many notable live-action feature-length films like The Public Enemy (1931), It Happened One Night (1934), and The Wizard of Oz (1939) delighted Depression-era audiences, animated cartoon shorts were also growing in popularity. The most important contributor to the evolution of animated cartoons in this era was Walt Disney, who innovated and perfected ideas that drastically changed cartoon production.2 Disney implemented new and experimental film technologies like synchronized sound and music, full-spectrum color, and the multiplane camera. With his contributions, cartoons sharply advanced in maturity and professionalism during the 1930s. The ultimate proof came with the release of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in 1937. The massive success of Snow White showed that animation could not only hold feature-length attention but tell a captivating story backed by impressive imagery that could rival any live- action film. However, it would take nearly a decade of experimentation at the Disney Studios before a project of this size and scope could be feasibly produced. While Mickey Mouse is often solely associated with 1930s-era Disney animation, many are unaware that alongside Mickey ran another popular series of shorts, the Silly Symphony cartoons. (SLIDE – SILLY SYMPHONY COLLAGE) The series ran from 1929-1940 and the subject matter covered everything from fables to original stories and even conceptual mood pieces. -

Winsor Mccay’S Dreams of a Rarebit

Anything Can Happen in a Cartoon: Comic Strip Adaptations in the Early and Transitional Periods Alex Kupfer [email protected] ARSC Research Award 1 Comic strips and motion pictures have had a symbiotic relationship from virtually their beginnings in the late nineteenth century. “As early as 1897, Frederick Burr Opper’s Happy Hooligan was adapted into a (live) movie series in which J. Stuart Blackton played the tramp.”1 The list of comic strips made into films during the silent era is extensive, and includes, but is not limited to: Winsor McCay’s Dreams of a Rarebit Fiend and Little Nemo in Slumberland, George McManus’ Bringing Up Father, Bud Fisher’s Mutt and Jeff, Fontaine Fox’s Toonerville Folks, Sidney Smith’s The Gumps, Rudolph Dirk’s Katzenjammer Kids, George Herriman’s Krazy Kat, and R.F. Outcault’s Hogan’s Alley and Buster Brown.2 With the rising popularity of animated cartoons beginning around 1908, comic strips became an even more popular source for motion picture producers to draw from. At the same time that animated films were becoming a regular part of exhibition, another important transformation in the development of the American film industry was occurring- the rise of the self-contained narrative film and the classical style filmmaking. Animated comic strip adaptations continued to be based on a model of filmmaking derived from vaudeville, emphasizing spectacle over narrative, well into the Classical Hollywood period. The films based on the strips by influential artists Winsor McCay and George Herriman are particularly noteworthy in this regard, since the cartoon versions based on their work are closer to the representational style of vaudeville than the comic strip medium.