IFF Report January 15, 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Certified School List MM-DD-YY.Xlsx

Updated SEVP Certified Schools January 26, 2017 SCHOOL NAME CAMPUS NAME F M CITY ST CAMPUS ID "I Am" School Inc. "I Am" School Inc. Y N Mount Shasta CA 41789 ‐ A ‐ A F International School of Languages Inc. Monroe County Community College Y N Monroe MI 135501 A F International School of Languages Inc. Monroe SH Y N North Hills CA 180718 A. T. Still University of Health Sciences Lipscomb Academy Y N Nashville TN 434743 Aaron School Southeastern Baptist Theological Y N Wake Forest NC 5594 Aaron School Southeastern Bible College Y N Birmingham AL 1110 ABC Beauty Academy, INC. South University ‐ Savannah Y N Savannah GA 10841 ABC Beauty Academy, LLC Glynn County School Administrative Y N Brunswick GA 61664 Abcott Institute Ivy Tech Community College ‐ Y Y Terre Haute IN 6050 Aberdeen School District 6‐1 WATSON SCHOOL OF BIOLOGICAL Y N COLD SPRING NY 8094 Abiding Savior Lutheran School Milford High School Y N Highland MI 23075 Abilene Christian Schools German International School Y N Allston MA 99359 Abilene Christian University Gesu (Catholic School) Y N Detroit MI 146200 Abington Friends School St. Bernard's Academy Y N Eureka CA 25239 Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College Airlink LLC N Y Waterville ME 1721944 Abraham Joshua Heschel School South‐Doyle High School Y N Knoxville TN 184190 ABT Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School South Georgia State College Y N Douglas GA 4016 Abundant Life Christian School ELS Language Centers Dallas Y N Richardson TX 190950 ABX Air, Inc. Frederick KC Price III Christian Y N Los Angeles CA 389244 Acaciawood School Mid‐State Technical College ‐ MF Y Y Marshfield WI 31309 Academe of the Oaks Argosy University/Twin Cities Y N Eagan MN 7169 Academia Language School Kaplan University Y Y Lincoln NE 7068 Academic High School Ogden‐Hinckley Airport Y Y Ogden UT 553646 Academic High School Ogeechee Technical College Y Y Statesboro GA 3367 Academy at Charlemont, Inc. -

From Starr to Santa, We've Loved a Parade

Product: OSBS PubDate: 12-23-2007 Zone: EST Edition: OR Page: ORSUFRT User: apinkston Time: 12-21-2007 13:43 Color: CMYK Inside: Book offers philosophy and side of laughs, J2 E SUNDAY ORANGE SECTION J SUNDAY Blog Former Knight, now Bronco in news DECEMBER 23, 2007 Extra One-time UCF great and current Bronco player Brandon Marshall gets attention at ESPN. OrlandoSentinel.com/ucfarea This Just In 1930s ‘Champs’ Ballot lawsuit needs spot on bands to judge’s docket fill streets Tim Adams, who has sued Orlando in an attempt to get his name on the ballot for the Jan. 29 Thursday mayor’s race, could be running out of time. By CHRISTOPHER SHERMAN There still hasn’t been a hear- SENTINEL STAFF WRITER ing in his case, and one scheduled for Friday was canceled. One Two clowns or a pair of floats problem is that Adams seems to might have trouble calling them- know several judges, who have selves a “parade,” but when two recused themselves as a result. university marching bands with a The game of musical judges has combined 600 students march now settled on Circuit Judge through downtown Winter Park on John Adams (no relation), but it Thursday, there will be no doubt. hasn’t been easy to find space on Michigan State University’s Adams’ calendar. Spartans and Boston College’s Tim Adams accuses Mayor Screaming Eagles will thunder Buddy Dyer’s administration of down Park Avenue the day before dirty politics in denying him the their respective football teams face right to have his name on the off in Orlando’s Champs Sports ballot. -

UP School Accounts

Alachua Account Value Owner Name Reporting Entity ‐‐ Source of Funds Type of Account 105916441 $32.45 OCHWILLA ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PTO, QSP INC ACCOUNTS PAYABLE 115227409 $5.07 LITTLE PIONEERS PRESCHOOL, COCA COLA REFRESHMENTS USA INC ACCOUNTS PAYABLE 115227410 $10.76 LITTLE PIONEERS PRESCHOOL, COCA COLA REFRESHMENTS USA INC ACCOUNTS PAYABLE 108967892 $27.15 POT OF GOLD HIGH SPRINGS FL, COCA COLA REFRESHMENTS USA INC ACCOUNTS PAYABLE 102962446 $120.00 LADY RAIDER BASKETBALL‐SANTA FE HIGH S, ALACHUA UTILITY CITY OF ACCOUNTS PAYABLE 113684402 $563.43 SANTA FE HIGH SCHOOL, COCA COLA REFRESHMENTS USA INC ACCOUNTS PAYABLE 120116250 $12.83 WALDO COMMUNITY SCHOOL, COCA COLA REFRESHMENTS USA INC CREDIT BALANCES ON ACCOUNTS 113684650 $24.75 WALDO COMMUNITY SCHOOL, COCA COLA REFRESHMENTS USA INC ACCOUNTS PAYABLE 111036494 $98.74 TRILOGY SCHOOL, COMPASS GROUP USA INC ACCOUNTS PAYABLE 104238730 $12.46 TRILOGY SCHOOL, BELLSOUTH TELECOMMUNICATIONS INC UTILITY DEPOSITS 6707767 $25.88 SUWANNEE CO BD OF PUB INST, AFLAC OF COLUMBUS 121223784 $53.79 SUCCESSFUL KIDS ACADEMY, PRIME RATE PREMIUM FINANCE CORPORATION REFUNDS 112909067 $175.00 ARCHER COMMUNITY SCHOOL, TIME INC SHARED SERVICES CREDIT BALANCES ON ACCOUNTS 122494000 $177.94 ARCHER COMMUNITY SCHOOL, DRUMMOND COMMUNITY BANK CASHIERS CHECKS 120115254 $18.34 ARCHER COMMUNTIY SCHOOL, COCA COLA REFRESHMENTS USA INC CREDIT BALANCES ON ACCOUNTS 122294130 $24.25 ARCHER COMMUNTIY SCHOOL, COCA COLA REFRESHMENTS USA INC CREDIT BALANCES ON ACCOUNTS 100388385 $51.60 FLOWERS MONTESSORI ACADEMY, LIFETOUCH NATIONAL -

Joseph L. Brechner Research Center Genealogy Resources

Joseph L. Brechner Research Center Genealogy Resources Hours: Monday – Friday, 10 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., Appointments are preferred Staff: Whitney Broadaway, Collections Manager [email protected], 407-836-8587 Garret B. Kremer-Wright , Archivist [email protected] , 407-836-8584 Adam Ware, Phd, Research Librarian [email protected] , 407-836-8541 1 Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………2 Archival Collections……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 Abstracts of Title……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Harold M. Beardall Collection…………………………………………………………………………………………………..3 City of Orlando Mayor’s Court Docket Ledgers………………………………………………………………………….3 City of Orlando Municipal Court Ledgers………………………………………………………………………………….3 City of Orlando Register of Births and Deaths…………………………………………………………………………...3 City of Orlando Voter Registration Ledgers………………………………………………………………………………3 Orange County Automobile Tag Ledger……………………………………………………………………………………3 Orange County Sheriff’s Department Collection………………………………………………………………………..3 Orange County Tax Collector Collection……………………………………………………………………………………3 Orange County Voter Registration Ledgers……………………………………………………………………………….4 Orlando High School Commencement Programs……………………………………………………………………….4 Photographic Collections……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………5 Biography……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….5 Business…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………18 Research Collections………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….21 -

OCPS District Directory

OCPS District Directory Florida Relay 7-1-1 Florida Telecommunications Relay, Inc., referred to as Florida Relay 7-1-1, is a communications link for people who are deaf, hard of hearing, deaf/blind, or speech impaired. For example, this service can be used when school staff members need to talk to a deaf parent or when the parent calls the school. Here is how it works: Hearing callers trying to reach deaf or hard-of-hearing callers dial 7-1-1 and give the operator the 10-digit telephone number of the person they are trying to reach. The operator will ask them if they have used the relay service before and give a short narrative if not. They will then ask the person to hold while the call is connected. The operator will type everything said by the hearing person and read back the responses from the D/HH caller. Once connected, the hearing person should speak at a slow-moderate rate and say “go ahead” when it is the caller’s turn to talk. This process is similar to two-way radios needing to say “over” as the conversation proceeds back and forth. The OCPS Telephone Directory is produced by the District Information Office. Please notify Wanda Cocco at 407-317-3237 or [email protected] of any changes or corrections. To order additional copies of the OCPS Telephone Directory, contact Printing Services at 407.850.5110, or e-mail your request to: [email protected]. OCPS EEO Non-Discrimination Statement The School Board of Orange County, Florida, does not discriminate in admission or access to, or treatment or employment in its programs and activities, on the basis of race, color, religion, age, sex, national origin, marital status, disability, genetic information, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, or any other reason prohibited by law. -

2018 Hoop Exchange Player Showdown Newsletter

First Name Last Name School Class Isaiah Adams Paxon School 2020 Latrell Aikens Evans High School 2020 Donovyn Akoon-Purcell Saints Academy 2018 Rodwens Albert Atlantic HS 2018 Brandon Alcide Triple Threat Prep 2018 Dino Alimanovic King High School 2018 Marlon Allen Boone HS 2019 Andre Alonzo Saint Brendan High School 2018 Nick Alves Melbourne Central Catholic 2018 Jashaun Amaker Atlantic Community High School 2020 James Ametepe Westwood Christian School 2018 Zachary Anderson Apopka HS 2020 Malik Anderson Triple Threat Prep 2018 Alston Andrews Ocoee High School 2020 Alex Andrews Ocoee High School 2020 Andy Antoine Evans High School 2019 Gim Atilus Post Grad - Bahamas 2018 Herbison Augustin Village Academy 2019 Oshea Baker Sanford Seminole HS 2020 Jaelen Bartlett Tabernacle Baptist 2019 Yussif Basa-Ama Westlake Prep 2020 Jose Luis Benitez Canelo School House Preparatory 2020 Murad Berrien Superior Collegiate Academy 2019 Carl Bigord School House Preparatory 2020 Anthony Bittar Oldsmar Christian 2021 Sadeem Blake Ocoee High School 2020 Joshua Blazquez Osceola HS 2021 Gabriel Borges The Rock School 2021 Troy Boynton Westminster Academy 2021 Marlon Bradley Deltona High School 2019 Tyrick Brascom Tampa Bay Technical 2018 Kirt Bromley Saint John Paul 2020 Terry Brown Gainesville High School 2020 Eric Brown Avon Park High 2020 Kamari Brown Triple Threat Prep 2018 Derrick Brown Vanguard HS 2019 Camaren Brown Olympia HS 2019 Cardinal Brown Miami Norland High School 2018 Matthew Brown University High School 2018 Dusan Bubanja Florida Elite Prep -

Coronavirus (COVID-19) Th on March 17 , Governor Desantis Announced All Schools Will Remain Closed Until April 15Th Due to COVID-19

Coronavirus (COVID-19) th On March 17 , Governor DeSantis announced all schools will remain closed until April 15th due to COVID-19. Distance learning instruction will begin on March 30th with instructions posted on the school website. During this time, free grab and go meals will rd be provided for children 18 and under at various locations beginning March 23 . This information will also be provided on the school website. Bridge to Independence is in constant communication with the Department of Health and the Department of Education regarding responses to COVID-19. As of March 22, there have been 830 cases confirmed in Florida and 13 residents have died. Bridge to Independence is following appropriate protocols to protect staff and students. The school has been disinfected and cleaned with this virus specifically in mind. We have contracted to provide a "deep cleaning" of the premises and removed unnecessary clutter to optimize cleaning efficiency. All of these services will be provided over spring break. When any person exhibits any of the symptoms listed below, he or she will be asked to stay home. Isolation limits the spread of the virus and will protect the overall health and wellness of others. Anyone with symptoms should call a medical provider for guidance on what to do. Medical providers will ask questions to screen people for COVID-19 or other illnesses, including the flu which is also prevalent this time of year. What is the Coronavirus (COVID-19)? * A virus that causes diseases of varying severities, ranging from the common -

WPHS Basketball Wins State Championship Sixth Annual Winter

The Park Press APRIL 2014 ~ Positive news that matters ~ FREE Winter Park | Baldwin Park | College Park | Audubon Park | Maitland SunRail Stamp Out In The Soft Hunger Garden Opening 4 11 17 ForFor updated updated news, news, events events and and more, more, visit visit www.TheParkPress.com www.TheParkPress.com WPHS Basketball Wins State Championship A promise made is a promise kept and that is what Coach Black- mon and the Wildcat basketball team are all about. The team carried an aura of confidence despite the odds against them this year. Coach Blackmon, who prior to this year was the assistant coach, took over the team this summer. He credits his predecessor, Coach Bailey, for laying the ground work for the team’s success this year. Coach Blackmon challenged his team to go beyond their limits and they did. Coach even offered to let the team shave off his salt and pepper locks if they won the state championships. Week after week his players played with heart and teamwork. The Wildcats clawed their way to the top of the heap and eventually landed themselves in the state champion- ship game against Evans High School. As district rivals this game was shaping up to be a battle between the titans of high school basket- ball. As time was running out in this epic matchup, Winter Park High trailed Evans 53-47. The Wildcats fought back with some clutch shots and closed the game for a Wildcat OT win 66-64. As promised, during our Spring Pep Rally, Coach Blackmon strolled out to the middle of the basketball court to meet his players- ready and waiting with clip- pers in hand. -

2007-2008 ALACHUA County

M E M O R A N D U M TO: District School Superintendents Music Supervisors and District Contacts FROM: David Lewis President, Florida School Music Association DATE: December 8, 2008 SUBJECT: 2007-08 State Music Performance Assessment Report Enclosed you will find the 2007-08 State Music Performance Assessment (MPA) Report for all the schools in your district that participated in the MPA activities, and a page that explains the various codes that appear in the report. If you wish to compare your district to other districts or the state, please visit our website at www.flmusiced.org where a complete copy of the State report is available (choose the FSMA logo on the home page). The Florida School Music Association (FSMA) coordinates and oversees all interscholastic music activities in the state of Florida. FSMA membership is required for schools that wish to participate in state sanctioned interscholastic music activities. FSMA sanctions the Florida Bandmaster’s Association (FBA), the Florida Orchestra Association (FOA), and the Florida Vocal Association (FVA) to sponsor District and State Music Performance Assessments for bands, orchestras, and choruses in Florida high schools, junior high schools, and middle schools. FSMA also sanctions student participation in the All-State performing ensembles sponsored by the Florida Music Educators’ Association (FMEA). The mission of FSMA is to ensure that member schools have safe, consistent, high-quality, educationally challenging and fiscally sound music events to expand the musicianship and skills -

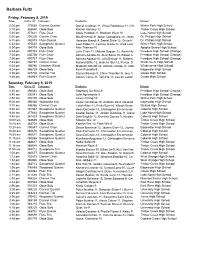

Barbara Fultz

Barbara Fultz Friday, February 8, 2019 Time Entry ID Category Students School 5:00 pm 375665 Clarinet Quartet Daniel Lindauer-11, Oliver Rodriguez-11, Chr Winter Park High School 5:10 pm 388640 Oboe Solo Rachel Ramsey-12 Timber Creek High School 5:30 pm 377621 Flute Duet Adele Haddad-11, Madison West-10 Lake Nona High School 5:50 pm 395226 Clarinet Choir Mia Benenati-9, Jodan Costagliola-10, Joshu Dr. Phillips High School 6:10 pm 392873 Flute Quartet Vanessa Brandt-9, Daniel Disla-12, Greta H Dr. Phillips High School 6:22 pm 375602 Saxophone Quartet Leon Edge-11, Corinne Guido-12, Kaia Leav Winter Park High School 6:34 pm 394774 Oboe Solo Alex Thomas-10 Apopka Senior High School 6:44 pm 400704 Flute Choir Leila Chair-11, Malena Dogaer-12, Alexa Hu Freedom High School (Orange) 7:04 pm 400706 Flute Choir Adriana Agosto-10, Alvin Bang-10, Edison C Freedom High School (Orange) 7:24 pm 400707 Flute Choir Adriana Agosto-10, Julia Biskup-11, Malena Freedom High School (Orange) 7:44 pm 396787 Clarinet Choir Holland Bittle-12, Isabella Bui-12, Renzo D Windermere High School 8:04 pm 396786 Chamber Winds Madison Bobroff-12, Anthony Borda-12, Isab Windermere High School 8:24 pm 396709 Oboe Solo Evan Psarakis-9 Edgewater High School 8:36 pm 397720 Clarinet Trio Saniya Ramjas-9, Chloe Thornton-9, Joey V Ocoee High School 8:46 pm 384948 Flute Quartet Ashtyn Cantu-11, Tam Ha-11, Lauren Lambi Ocoee High School Saturday, February 9, 2019 Time Entry ID Category Students School 8:30 am 396044 Oboe Solo Stephany Da Silva-9 Freedom High School (Orange) 8:40 -

High School Programs for High Ability Students. Program Evaluation Report. INSTITUTION Orange County Public Schools, Orlando, Fla

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 357 529 EC 302 071 AUTHOR Thomas, Roberta Rodriguez TITLE High School Programs for High Ability Students. Program Evaluation Report. INSTITUTION Orange County Public Schools, Orlando, Fla. PUB DATE Jun 92 NOTE 45p. PUB TYPE Reports Evaluative/Feasibility (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Ability Identification; *Academically Gifted; *Advanced Courses; Advanced Placement; *Curriculum Evaluation; Educational Needs; Financial Exigency; High Schools; High School Students; Honors Curriculum; Magnet Schools; *Program ':valuation; School Demography; Student Attitudes; Student Placement IDENTIFIERS *Orange County Public Schools FL ABSTRACT This evaluation report examines high schoolprograms for high ability students in Orange County, California. The evaluation study used interviews, surveys, anda review of records. It was found that: (1) all high schools have developeda course of study for high ability students, including Advanced Placement, honors, and four magnet programs;(2) all schools have a process for identifying high ability students and directing them tomore rigorous academic courses; (3) those schools with course/program analysis systems in place were found to be more fully meeting student needs; (4) most students felt that courseswere preparing them adequately for the next level courses;(5) major concerns expressed by administrators and practitioners focused on threats to theseprograms as a result of reduced funding;(6) almost all schools utilized district-level incentive funds in program development; and (7)the implications of changing demographics have not been fully incorporated into program planning. The report briefly presentsthe purpose of the evaluation, related district goals, the program description, evaluation questions, and procedures. Most of thereport is given to analysis of findings and recommendations for eachschool. -

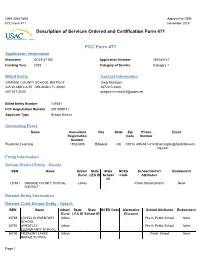

Description of Services Ordered and Certification Form 471 FCC Form

OMB 3060-0806 Approval by OMB FCC Form 471 November 2015 Description of Services Ordered and Certification Form 471 FCC Form 471 Application Information Nickname OC18-47103 Application Number 181042141 Funding Year 2018 Category of Service Category 1 Billed Entity Contact Information ORANGE COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT Greg McIntosh 445 W AMELIA ST ORLANDO FL 32801 407-317-3200 407-317-3200 [email protected] Billed Entity Number 127681 FCC Registration Number 0011598141 Applicant Type School District Consulting Firms Name Consultant City State Zip Phone Email Registration Code Number Number Funds for Learning 16024808 Edmond OK 73013 405-341-4140 jharrington@fundsforlearn ing.com Entity Information School District Entity - Details BEN Name Urban/ State State NCES School District Endowment Rural LEA ID School Code Attributes ID 127681 ORANGE COUNTY SCHOOL Urban Public School District None DISTRICT Related Entity Information Related Child School Entity - Details BEN Name Urban/ State State NCES Code Alternative School Attributes Endowment Rural LEA ID School ID Discount 35788 LOVELL ELEMENTARY Urban Pre-K; Public School None SCHOOL 35794 WHEATLEY Urban Pre-K; Public School None ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 35795 PIEDMONT LAKES Urban Public School None MIDDLE SCHOOL Page 1 BEN Name Urban/ State State NCES Code Alternative School Attributes Endowment Rural LEA ID School ID Discount 35796 PRAIRIE LAKE Urban None Pre-K; Public School None ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 35809 APOPKA ELEMENTARY Urban None Pre-K; Public School None SCHOOL 35811 DREAM LAKE Urban None