Impacts of Terrorism-Related Safety and Security Measures at a Major Sport Event

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rugby World Cup Quiz

Rugby World Cup Quiz Round 1: Stats 1. The first eight World Cups were won by only four different nations. Which of the champions have only won it once? 2. Which team holds the record for the most points scored in a single match? 3. Bryan Habana and Jonah Lomu share the record for the most tries in the final stages of Rugby World Cup Tournaments. How many tries did they each score? 4. Which team holds the record for the most tries in a single match? 5. In 2011, Welsh youngster George North became the youngest try scorer during Wales vs Namibia. How old was he? 6. There have been eight Rugby World Cups so far, not including 2019. How many have New Zealand won? 7. In 2003, Australia beat Namibia and also broke the record for the largest margin of victory in a World Cup. What was the score? Round 2: History 8. In 1985, eight rugby nations met in Paris to discuss holding a global rugby competition. Which two countries voted against having a Rugby World Cup? 9. Which teams co-hosted the first ever Rugby World Cup in 1987? 10. What is the official name of the Rugby World Cup trophy? 11. In the 1995 England vs New Zealand semi-final, what 6ft 5in, 19 stone problem faced the English defence for the first time? 12. Which song was banned by the Australian Rugby Union for the 2003 World Cup, but ended up being sang rather loudly anyway? 13. In 2003, after South Africa defeated Samoa, the two teams did something which touched people’s hearts around the world. -

Notes About This Report

NRS Estimates of Average Issue Readership for latest 12 & 6 month periods Ending June 200 Media Release September 19th, 2005 For the first time, NRS is producing a set data for journalists and media commentators to help them identify and quantify changes in the survey’s readership estimates. These tables will now be updated every quarter, and will be available via email or via the NRS website (in the subscribers-only section) at www.nrs.co.uk. Notes About This Report This report shows NRS Average Issue Readership estimates sorted by publication group (daily newspapers, Sunday newspapers, general weekly magazines etc.) for two data periods, 12 months and 6 months. Virtually all publications are reported on the 12-month base*, but only those with a sufficient sample size are reported on the 6-month base. The first column is the estimate (in 000s) for the most recent data period, the second column the estimate for the equivalent period a year ago. The third and fourth columns show the difference in the estimates between those periods, expressed in 000s and as a plus or minus percentage change. It is important to note that – as with any other sample-based survey - NRS estimates are subject to sampling variation. If two independent samples of the population are interviewed – which is what NRS is doing each year – the estimates obtained from these samples may be different, but if the differences are relatively small, they may be due simply to sampling variation. Therefore, when making any period-on-period comparison, it is important to express it as a change in the readership estimate, rather than a change in the actual readership. -

Legacy – the All Blacks

LEGACY WHAT THE ALL BLACKS CAN TEACH US ABOUT THE BUSINESS OF LIFE LEGACY 15 LESSONS IN LEADERSHIP JAMES KERR Constable • London Constable & Robinson Ltd 55-56 Russell Square London WC1B 4HP www.constablerobinson.com First published in the UK by Constable, an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd., 2013 Copyright © James Kerr, 2013 Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologise for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition. The right of James Kerr to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in Publication data is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-47210-353-6 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-47210-490-8 (ebook) Printed and bound in the UK 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Cover design: www.aesopagency.com The Challenge When the opposition line up against the New Zealand national rugby team – the All Blacks – they face the haka, the highly ritualized challenge thrown down by one group of warriors to another. -

2021 Major Sports Events Calendar Last Update: January 2021

2021 Major Sports Events Calendar Last update: January 2021 AMERICAN FOOTBALL Throughout 2021 National Football League - - Throughout 2021 NCAA Men's Football - - 7 Feb Super Bowl LV - TBC NFL International Series - - ATHLETICS Throughout 2021 IAAF Diamond League - - 5-7 Mar European Athletics Indoor Championship - - - 26 Sep Berlin Marathon 3 Oct London Marathon TBC 10 Oct Chicago Marathon TBC TBC 17 Oct Paris Marathon - 17 Oct Tokyo Marathon TBC 7 Nov New York Marathon TBC TBC Boston Marathon TBC TBC BASEBALL Throughout 2021 MLB regular season - - 20-30 Aug Little League World Series - - - October MLB World Series TBC BASKETBALL Throughout 2021 NBA regular season - Throughout 2021 NCAA Men's Basketball - - TBD NCAA Women’s Basketball Postseason - - 28-30 May EuroLeague Final Four - - May-July NBA Playoffs - COMBAT Throughout 2021 MMA and UFC Title Fights - Throughout 2021 Boxing World Title Fights - This calendar is for editorial planning purposes only and subject to change For a real-time calendar of coverage, visit reutersconnect.com/planning CRICKET Throughout 2021 Test matches - - Aug-Sep Test matches - England v India Throughout 2021 ODI matches - - TBC Throughout 2021 T20 matches - - - Oct-Nov ICC Men's T20 Cricket World Cup TBC CYCLING 8-30 May Giro D'Italia TBC 26 Jun - 18 Jul Tour de France 14 Aug - 5 Sep La Vuelta 19-26 Sep UCI Road Cycling World Championships - TBC TBC 13-17 Oct UCI Track Cycling World Championships - TBC TBC Throughout 2021 Top international races - ESPORTS Throughout 2021 Call of Duty League - - - Throughout 2021 DOTA 2 - - - TBC DOTA 2 - The International 10 TBC - - Throughout 2021 ESL One & IEM Tournaments TBC - - TBC FIFAe major competitions TBC - - Throughout 2021 League of Legends - - - TBC League of Legends World Championship TBC - - Throughout 2021 NBA2K League - - - Throughout 2021 Overwatch League - - - GOLF Throughout 2021 PGA TOUR Throughout 2021 European Tour - - - Throughout 2021 LPGA Tour TBC TBC - 8-11 April Masters - TBC 20-23 May PGA Championship - TBC 17-20 Jun U.S. -

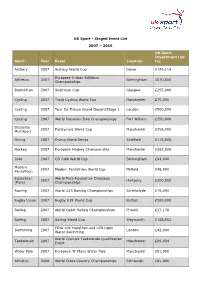

Staged Event List 2007 – 2019 Sport Year Event Location UK

UK Sport - Staged Event List 2007 – 2019 UK Sport Investment (up Sport Year Event Location to) Archery 2007 Archery World Cup Dover £199,114 European Indoor Athletics Athletics 2007 Birmingham £570,000 Championships Badminton 2007 Sudirman Cup Glasgow £255,000 Cycling 2007 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £75,000 Cycling 2007 Tour De France Grand Depart/Stage 1 London £500,000 Cycling 2007 World Mountain Bike Championships Fort William £250,000 Disability 2007 Paralympic World Cup Manchester £358,000 Multisport Diving 2007 Diving World Series Sheffield £115,000 Hockey 2007 European Hockey Championship Manchester £262,000 Judo 2007 GB Judo World Cup Birmingham £94,000 Modern 2007 Modern Pentathlon World Cup Milfield £48,000 Pentathlon Equestrian World Para-Equestrian Dressage 2007 Hartpury £200,000 (Para) Championships Rowing 2007 World U23 Rowing Championships Strathclyde £75,000 Rugby Union 2007 Rugby U19 World Cup Belfast £289,000 Sailing 2007 World Cadet Sailing Championships Phwelli £37,178 Sailing 2007 Sailing World Cup Weymouth £168,962 FINA 10K Marathon and LEN Open Swimming 2007 London £42,000 Water Swimming World Olympic Taekwondo Qualification Taekwondo 2007 Manchester £99,034 Event Water Polo 2007 European 'B' Mens Water Polo Manchester £81,000 Athletics 2008 World Cross Country Championships Edinburgh £81,000 Boxing 2008 European Boxing Championships Liverpool £181,038 Cycling 2008 World Track Cycling Championships Manchester £275,000 Cycling 2008 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £111,000 Disability 2008 Paralympic World -

The Future of Rugby: an HSBC Report

The Future of Rugby: An HSBC Report #futureofrugby HSBC World Rugby Sevens Series 2015/16 VANCOUVER 12-13 March 2016 LONDON PARIS LANGFORD 21-22 May 2016 14-15 May 2016 16-17 April 2016 CLERMONT-FERRAND 28-29 May 2016 ATLANTA DUBAI 9-10 April 2016 LAS VEGAS 4-5 December 2016 4-6 March 2016 HONG KONG 8-10 April 2016 DUBAI 4-5 December 2016 SINGAPORE 16-17 April 2016 SÃO PAULO CAPE TOWN SYDNEY 20-21 February 2016 12-13 December 2016 6-7 February 2016 WELLINGTON KEY 29-30 January 2016 HSBC Men’s World Rugby Sevens Series HSBC Women’s World Rugby Sevens Series Catch all the latest from the HSBC World Rugby Sevens Series 2015/16 HSBC Sport 1985 1987 1993 1998 1999 2004 2009 2011 2016 International First Rugby First Rugby Rugby is World Rugby sevens The IOC Pan Rugby Rugby Board World Cup World Cup added to Sevens added to votes to American returns votes to set is hosted Sevens Common- Series World add rugby Games to the up Rugby jointly by wealth launched University to the includes Olympics World Cup Australia Games and Championships Olympics rugby and New Asian Games sevens Zealand The 30- year road to Rio 1991 1997 2004 2009 2010 2011 2015 2016 First First Women’s First Women’s First Women’s Women’s women’s women’s sevens at Women’s sevens Women’s sevens at sevens Rugby sevens World Sevens at Asian Sevens the Pan at the World Cup tournament University World Cup Games World American Olympics (fifteens) at Hong Championships Series Games Kong “The IOC [International Olympic Committee] is looking for sports that will attract a new fan base, new -

ABC Consumer Magazine Concurrent Release - Dec 2007 This Page Is Intentionally Blank Section 1

December 2007 Industry agreed measurement CONSUMER MAGAZINES CONCURRENT RELEASE This page is intentionally blank Contents Section Contents Page No 01 ABC Top 100 Actively Purchased Magazines (UK/RoI) 05 02 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Total Average Net Circulation/Distribution 09 03 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Total Average Net Circulation/Distribution (UK/RoI) 13 04 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Circulation/Distribution Increases/Decreases (UK/RoI) 17 05 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Actively Purchased Increases/Decreases (UK/RoI) 21 06 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Newstrade and Single Copy Sales (UK/RoI) 25 07 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Single Copy Subscription Sales (UK/RoI) 29 08 ABC Market Sectors - Total Average Net Circulation/Distribution 33 09 ABC Market Sectors - Percentage Change 37 10 ABC Trend Data - Total Average Net Circulation/Distribution by title within Market Sector 41 11 ABC Market Sector Circulation/Distribution Analysis 61 12 ABC Publishers and their Publications 93 13 ABC Alphabetical Title Listing 115 14 ABC Group Certificates Ranked by Total Average Net Circulation/Distribution 131 15 ABC Group Certificates and their Components 133 16 ABC Debut Titles 139 17 ABC Issue Variance Report 143 Notes Magazines Included in this Report Inclusion in this report is optional and includes those magazines which have submitted their circulation/distribution figures by the deadline. Circulation/Distribution In this report no distinction is made between Circulation and Distribution in tables which include a Total Average Net figure. Where the Monitored Free Distribution element of a title’s claimed certified copies is more than 80% of the Total Average Net, a Certificate of Distribution has been issued. -

The Culture of Alcohol Promotion and Consumption at Major Sports Events in New Zealand

The culture of alcohol promotion and consumption at major sports events in New Zealand Research report commissioned by the Health Promotion Agency Authors: Dr Sarah Gee Professor Steve J. Jackson Dr Michael Sam August 2013 ISBN: 978-1-927224-58-8 (online) Citation: Gee, S., Jackson, S. J. & Sam, M. (2013). The culture of alcohol promotion and consumption at major sports events in New Zealand: Research report commissioned by the Health Promotion Agency. Wellington: Health Promotion Agency. This document is available at: www.hpa.org.nz Any queries regarding this report should be directed to HPA at the following address: Health Promotion Agency Level 4, ASB House 101 The Terrace Wellington 6011 PO Box 2142 Wellington 6140 New Zealand August 2013 COMMISSIONING CONTACTS COMMENTS: The Health Promotion Agency (HPA) commission was managed by Mark Lyne, Principal Advisor Drinking Environments. In order to support effective event planning and management, HPA sought to commission research to explore the relationship between sport, alcohol and the sponsorship of alcohol at large events. Dr Sarah Gee of Massey University, a specialist in the associations between alcohol and sport, was commissioned in 2011 to undertake the research. The report presents findings from four case studies, each of a large alcohol-sponsored sporting event in New Zealand. Data was collected via ethnographic observation, in situ surveys and broadcast content analysis. The analysis provides a critical reflection of the role of alcohol-sponsorship in the culture of large sporting events in New Zealand. Those with interest in an increasingly complex nexus between sport, alcohol and culture, as well as those interested in the use of mixed method approaches for social inquiry, will find the report highly valuable. -

UK Sport - Staged Event List

UK Sport - Staged Event List 2007 – 2019 UK Sport Investment (up Sport Year Event Location to) Archery 2007 Archery World Cup Dover £199,114 European Indoor Athletics Athletics 2007 Birmingham £570,000 Championships Badminton 2007 Sudirman Cup Glasgow £255,000 Cycling 2007 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £75,000 Cycling 2007 Tour De France Grand Depart/Stage 1 London £500,000 Cycling 2007 World Mountain Bike Championships Fort William £250,000 Disability 2007 Paralympic World Cup Manchester £358,000 Multisport Diving 2007 Diving World Series Sheffield £115,000 Hockey 2007 European Hockey Championship Manchester £262,000 Judo 2007 GB Judo World Cup Birmingham £94,000 Modern 2007 Modern Pentathlon World Cup Milfield £48,000 Pentathlon Equestrian World Para-Equestrian Dressage 2007 Hartpury £200,000 (Para) Championships Rowing 2007 World U23 Rowing Championships Strathclyde £75,000 Rugby Union 2007 Rugby U19 World Cup Belfast £289,000 Sailing 2007 World Cadet Sailing Championships Phwelli £37,178 Sailing 2007 Sailing World Cup Weymouth £168,962 FINA 10K Marathon and LEN Open Swimming 2007 London £42,000 Water Swimming World Olympic Taekwondo Qualification Taekwondo 2007 Manchester £99,034 Event Water Polo 2007 European 'B' Mens Water Polo Manchester £81,000 Athletics 2008 World Cross Country Championships Edinburgh £81,000 Boxing 2008 European Boxing Championships Liverpool £181,038 Cycling 2008 World Track Cycling Championships Manchester £275,000 Cycling 2008 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £111,000 Disability 2008 Paralympic World -

The Super Yacht

BRINGS The Super Yacht TO LONDON FOR THE RUGBY WORLD CUP 30TH SEPTEMBER - 31ST OCTOBER At Lillingston we don’t just arrange We have a global reach and we can WHY events. We create unforgettable take you anywhere in the world in experiences. sheer luxury. Our team are hugely LILLINGSTON experienced professionals who can Whether you’d like us to escort you make the impossible happen, down to and your guests to one of the world’s the last tiny detail. most dazzling prestige occasions or to create a bespoke adventure unlike Our aim is simple. Utter perfection. anything you’ve experienced, this goes far beyond standard corporate or VIP entertaining. Every occasion we organise is lit up by beautiful personal touches and given an extra dimension of glamour and excitement. Whatever you envisage, we can make it even more brilliant and original than you hoped. LILLINGSTON International Event Creators 3 — SPORT MISCHIEF - RUGBY WORLD CUP WORLD MISCHIEF - RUGBY OUR SUPER YACHT LILLINGSTON International Event Creators 4 — THE SUPERYACHT MISCHIEF - RUGBY WORLD CUP WORLD MISCHIEF - RUGBY MISCHIEF 30TH SEPTEMBER - 31ST OCTOBER 2015 Lillingston are proud to announce the arrival of MISCHIEF the 54 metre Super Yacht for the 2015 Rugby World Cup in London. The yacht will be moored on the River Thames and will host a series of very unique and special events integrating the true Spirit of Rugby. Hop aboard MISCHIEF and enjoy the company of high profile Rugby Legends and sensational cuisine prepared by world renowned Super Chefs, whilst afloat on the River -

Jeffrey Archer Charity Sale Realises £402,100 / $640,143 / €452,765

For Immediate Release 27 June 2011 Contact: Matthew Paton [email protected] +44 207 389 2664 JEFFREY ARCHER CHARITY SALE REALISES £402,100 / $640,143 / €452,765 Jeffrey Archer takes to the rostrum for his evening charity auction which sells 18 objects - with all proceeds to benefit charitable causes Top price paid for the chief timekeeper’s stopwatch that recorded Roger Bannister’s first four minute mile - £97,250 / $154,822 / 109,504 A handbag donated by Lady Thatcher sells for £25,000 / $39,800 / €28,150 London – The Jeffrey Archer Charity Sale realized £402,100 / $640,143 / €452,765. The gala auction saw Jeffrey Archer act as auctioneer and sell 18 lots including mementos, collectible relics and items, both from Lord Archer’s personal collection, together with additional donations from several famous public figures including The Rt Hon the Baroness Thatcher, Eric Clapton, Bernie Ecclestone, Lawrence Dallaglio, Sir Michael Parkinson and Ian Botham. All proceeds will benefit charitable causes. Highlights: - Sold for £97,250 / $154,822 / €109,504 - The senior timekeeper’s stopwatch that recorded Roger Bannister’s first four minute mile at Iffley Road on 6 May 1954, which was donated by Lord Archer with proceeds to benefit Oxford University Athletics Club. - Sold for £25,000 / $39,800 / €28,150 - a handbag donated by The Rt Hon the Baroness Thatcher, owned by her for over thirty years and famously pictured with the former Prime Minister alongside US President Ronald Reagan during her famous visit to the United States in 1985. Proceeds to benefit Combat Stress, The British Forces Foundation and Debra. -

OCTOBER 2019 TIME TABLE 10 2019.10.1 ▶ 10.31 J SPORTS 2 ★ First on Air

OCTOBER 2019 TIME TABLE 10 2019.10.1 ▶ 10.31 J SPORTS 2 ★ First On Air Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun Mon 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 4.00 Blank 4.00 Blank 4.00 Blank 4.00 Blank 4.00 Cycle* Warera World #5 10.30 Rugby World Cup Daily News 4.00 Blank 6.00 Rugby World Cup Daily News 6.00 Rugby World Cup Daily News 6.00 Rugby World Cup Daily News◇World Rugby #39 6.00 Rugby World Cup Daily News 4.30 Documentary -The REAL- 11.00 WWE RAW #1374 HL 6.00 Rugby World Cup Daily News 6.30 Mobil 1 The Grid #17 6.30 Rugby World Cup #2 Weekly HL 7.00 Foot!◇J SPORTS HOOP! #10 6.30 Cycle* Warera World #5 5.30 Rugby World Cup Daily News 0.00 Documentary -The REAL- 6.30 Daily Soccer News Foot! 7.00 Foot!◇World Rugby #39 7.30 Daily Soccer News Foot! 8.00 Kanto University Basketball Rookies' Tornament 7.00 Foot!◇FIBA 3x3 World Tour HL 6.00★MLB Post Season 1.00 MLB Players #6 7.30 Documentary -The REAL- 8.00 Nippon Sport Science Basketball 8.00 The 68th Kanto Collegiate Basketball Semifinal-1「Tokai Univ. vs. 8.00 Kanto University Basketball Rookies' Division Series 1.10★Rugby World Cup 8.30★MLB Post Season Selection Ranking match Tournament 5th place decision Nippon Sport Science Univ.」 Tornament 3rd place decision NLDS-A Game2(10/04) Japan Report Pool B Division Series 「Nippon Sport Science Univ vs.