Finland 2009-10Def

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Handball Statistics Feeds

Updated 08.17.18 Handball Statistics Feeds 2016 1 SPORTRADAR HANDBALL STATISTICS FEEDS Updated 08.17.18 Table of Contents Handball Statistics Feeds ........................................................................................................................... 3 Coverage Levels ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Language Support ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Category & Sport Information ................................................................................................................... 6 Tournament Information ............................................................................................................................. 8 Competitor Information .............................................................................................................................11 Player Information .......................................................................................................................................13 Venue Information .......................................................................................................................................14 Probability Information ..............................................................................................................................16 Sport Event Information ............................................................................................................................17 -

REPORT on the Free Movement of Workers in Finland in 2011-2012 Rapporteur: Eeva Nykänen University of Turku November 2012

REPORT on the Free Movement of Workers in Finland in 2011-2012 Rapporteur: Eeva Nykänen University of Turku November 2012 1 FINLAND Contents Introduction Chapter I The Worker: Entry, residence, departure and remedies Chapter II Members of the family Chapter III Access to employment Chapter IV Equality of treatment on the basis of nationality Chapter V Other obstacles to free movement of workers Chapter VI Specific issues Chapter VII Application of transitional measures Chapter VIII Miscellaneous 2 FINLAND Introduction The question of free movement of EU workers did not raise any substantial debate in Finland in 2011-2012 and no significant legislative amendments took place in this field. It seems that the general hardening of the attitudes towards foreigners has not had any major impact on the treatment and position of EU workers. Incidents of direct discrimination against EU workers come up only very rarely. There are, however, indications of that posted workers are more exposed to discrimination than directly employed persons. It is not un- common that posted workers are paid less than the directly employed employees; they are not paid supplementary payments such as overtime pay; they are not insured; and no occupa- tional health care is arranged. However, incidents of discrimination against posted workers proceed to courts only very rarely. Implementation of the legislation on free movement of workers covers the activities of several ministries and other bodies, whose work impacts on the rights of EU workers work- ing in Finland. The Ministry of Interior is responsible for the legislation concerning EU citi- zen’s entry, residence and removal. -

The Team Handball Game-Based Performance Test Is Better Than The

applied sciences Article The Team Handball Game-Based Performance Test Is Better than the Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test to Measure Match-Related Activities in Female Adult Top-Elite Field Team Handball Players Lars Bojsen Michalsik 1,*, Patrick Fuchs 2 and Herbert Wagner 2 1 Department of Sport Science and Clinical Biomechanics, Muscle Physiology and Biomechanics Research Unit, University of Southern Denmark, Campusvej 55, 5230 Odense M., Denmark 2 Department of Sport and Exercise Science, University of Salzburg, Schlossallee 49, Hallein-Rif, 5400 Salzburg, Austria; [email protected] (P.F.); [email protected] (H.W.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: In team handball, suitable tests determining the match-related physical performance are essential for the planning of optimal physical training regimens. Thus, the aims of the present study were (a) to determine the relationships between the physical and physiological test results from a team handball game-based performance test (GBPT), the Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test, level 1 (Yo-Yo IR1 test) and a separate linear 30-m single sprint performance test (SSPT) in female adult top-elite field team handball players, in order to establish the significance (validity) of tests for measuring relevant elements for team handball match-play; and (b) to compare and evaluate Citation: Michalsik, L.B.; Fuchs, P.; Wagner, H. The Team Handball the results from the aforementioned tests for the same players in relation to the different playing Game-Based Performance Test Is positions. Twenty-three female adult top-elite field team handball players from the Danish Premier Better than the Yo-Yo Intermittent Female Team Handball League performed the GBPT, the Yo-Yo IR1 test and the 30-m SSPT test on Recovery Test to Measure separate days. -

Sport, Recreation and Green Space in the European City

Sport, Recreation and Green Space in the European City Edited by Peter Clark, Marjaana Niemi and Jari Niemelä Studia Fennica Historica The Finnish Literature Society (SKS) was founded in 1831 and has, from the very beginning, engaged in publishing operations. It nowadays publishes literature in the fields of ethnology and folkloristics, linguistics, literary research and cultural history. The first volume of the Studia Fennica series appeared in 1933. Since 1992, the series has been divided into three thematic subseries: Ethnologica, Folkloristica and Linguistica. Two additional subseries were formed in 2002, Historica and Litteraria. The subseries Anthropologica was formed in 2007. In addition to its publishing activities, the Finnish Literature Society maintains research activities and infrastructures, an archive containing folklore and literary collections, a research library and promotes Finnish literature abroad. Studia fennica editorial board Markku Haakana Timo Kaartinen Pauli Kettunen Leena Kirstinä Teppo Korhonen Hanna Snellman Kati Lampela Editorial Office SKS P.O. Box 259 FI-00171 Helsinki www.finlit.fi Sport, Recreation and Green Space in the European City Edited by Peter Clark, Marjaana Niemi & Jari Niemelä Finnish Literature Society · Helsinki Studia Fennica Historica 16 The publication has undergone a peer review. The open access publication of this volume has received part funding via a Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation grant. © 2009 Peter Clark, Marjaana Niemi, Jari Niemelä and SKS License CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International A digital edition of a printed book first published in 2009 by the Finnish Literature Society. Cover Design: Timo Numminen EPUB Conversion: Tero Salmén ISBN 978-952-222-162-9 (Print) ISBN 978-952-222-791-1 (PDF) ISBN 978-952-222-790-4 (EPUB) ISSN 0085-6835 (Studia Fennica) ISSN 1458-526X (Studia Fennica Historica) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21435/sfh.16 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License. -

Source : Bibliothèque Du CIO / IOC Library BASKETBALL COMMITTEE

In the semi-finals competition stiffened. In the same group were now the U.S.A. and the U.S.S.R., neither of whom had so far been fully extended. But first the other group. Here only one match was won by a handsome margin; in none of the others was the winner more than 9 points ahead. Uruguay played two heated, furious matches, losing by two The basketball matches were played in two different arenas: the eliminating matches and points to France with only three Uruguayans on the court when the match ended. The the opening round of the tournament in the Tennis Palace in the heart of the city, where referee had to be carried to a dressing room after a regrettable scene. The other ended in two courts had been available for practice, and the semi-finals and finals in Messuhalli II, Uruguay's favour, Argentine, who had played the best basketball in the first round, losing adjacent to the Olympic Stadium. by one point. Bulgaria's awkward style seemed to keep France puzzled, with the result Dressing rooms, showers and the practice courts made the Tennis Palace a very good that she failed to make the top final group. The French players were curiously slack in venue, but unfortunately there was little space for the public. In Messuhalli II, again, the this match. Argentine defeated France by nine goals and Uruguay Bulgaria by eight. In barriers of the spectator stands at the two ends were perilously close to the play-area. The her match with Bulgaria Argentine piled up 100 goals. -

Study on the Sharing of Information and Reporting of Suspicious Sports

Study on the sharing of information and reporting of suspicious sports betting activity in the EU 28 A study for DIRECTORATE‐GENERAL EDUCATION AND CULTURE, Directorate Youth and Sport, Unit Sport FINAL REPORT Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you). More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2014 ISBN 978-92-79-39389-1 doi: 10.2766/8026 © European Union, 2014 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Study on the sharing of information and reporting of suspicious sports betting activity in the EU 28 HOW TO OBTAIN EU PUBLICATIONS Free publications: • one copy: via EU Bookshop (http://bookshop.europa.eu); • more than one copy or posters/maps: from the European Union’s representations (http://ec.europa.eu/represent_en.htm); from the delegations in non-EU countries (http://eeas.europa.eu/delegations/index_en.htm); by contacting the Europe Direct service (http://europa.eu/europedirect/index_en.htm) or calling 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (freephone number from anywhere in the EU) (*). (*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you). Priced publications: • via EU Bookshop (http://bookshop.europa.eu). Priced subscriptions: • via one of the sales agents of the Publications Office of the European Union (http://publications.europa.eu/others/agents/index_en.htm). -

European Team Championships 1St League • Biographical Entrylist

Lane Age (Days) Year SB PB 100m European Team Championships CR 11.11 Ivet Lalova-Collio BUL 2015 1st League • Biographical Entrylist, Women TSIMANOUSKAYA Krystsina BLR 24y 212d 1996 11.22 11.04 -18 100m European U23 Silver 2017 / 200m Universiade Champion 2019 / 17 National Titles (5x 100 outdoors 2016/2017/2018/2019/2020) (5x 200 outdoors 2016/2017/2018/2019/2020) (3x 200 indoors 2017/2019/2020) (4x 60 indoors 2017/2018/2020/2021) 100m pb 11.04 NU23R Minsk -18 150 17.57 Pliezhausen -16 200 22.78 Minsk -19 6 EJ 100 2015 (h 200, h 4x1); sf EICh 60 2017; 2 U23 ECh 100 2017 (4 200); sf ECH 100 2018 (sf 200); h WICh 60 2018; 7 EICh 60 2019; h WCH 200 2019; 6 WSG 100 2019 (1 200); DQ EICh 60 2021 Born in Klimavichy. In 2021: 1 Mogilyov 60 ind; 3 Mondeville 60 ind; 8 Liévin 60 ind; 1 indoor 60 ind; 1 St. Pölten Prokop 100 (11.22); 1 Eisenstadt 100 (11.20w); 2 Athína 100 (11.79) KORA Salomé SUI 27y 11d 1994 11.12 11.12 -21 4 x 100m 4th at World Ch 2019 / 4 x 100m 5th at World Ch 2017 / 4 x 100m Universiade Champion 2019 / 4 x 100m Universiade Champion 2017 / 100m Universiade Bronze 2017 100m pb 11.12 Genève -21 150 17.29 Basel -16 200 23.92 St. Gallen -16 h U23 ECh 100 2015; 4 ECH 4x1 2016 (sf 100); h OLY 4x1 2016; 5 WCH 4x1 2017 (sf 100); 3 WSG 100 2017 (1 4x1); 4 ECH 4x1 2018 (sf 100); 4 WCH 4x1 2019 (h 100); 4 WSG 100 2019 (1 4x1); sf EICh 60 2021 Born in St. -

Livebetting in Sportlife Page 1

LIVEbetting in SportLife kickoff_time sport competition_name home_name away_name 2017-06-03 11:30:00 FOOTBALL Australia NPL South Australian Campbelltown City West Adelaide 2017-06-03 11:30:00 BASKETBALL Australia SEABL Dandenong Rangers Kilsyth Cobras 2017-06-03 11:30:00 BASKETBALL Australia SEABL Nunawading Spectres Geelong Supercats 2017-06-03 12:00:00 FOOTBALL Poland III Liga Legia Warsaw II LKS Lodz 2017-06-03 12:00:00 FOOTBALL Vietnamese Cup Sanna Khanh Hoa Ho Chi Minh City 2017-06-03 12:00:00 FOOTBALL Kazakhstan Premier League FC Tobol Kostanay Kaisar Kyzylorda 2017-06-03 12:00:00 BASKETBALL Australia SEABL Bendigo Braves Melbourne Tigers 2017-06-03 12:00:00 FOOTBALL India U19 IFA Shield Minerva Punjab U19 Pune FC U19 2017-06-03 12:00:00 BASKETBALL Australia SEABL Albury Wodonga Bandits Canberra Gunners 2017-06-03 12:00:00 FOOTBALL Vietnamese Cup Da Nang Thanh Hoa 2017-06-03 12:00:00 FOOTBALL India U19 IFA Shield Mohun Bagan U19 Tata U19 2017-06-03 12:00:00 FOOTBALL Japan J-League Fagiano Okayama JEF Utd Chiba 2017-06-03 12:00:00 FOOTBALL Japan J-League 2 Thespa Kusatsu Tokushima Vortis 2017-06-03 12:00:00 FOOTBALL Estonia Meistriliiga Paide Linnameeskond JK Nomme Kalju 2017-06-03 12:00:00 FOOTBALL South Korea K-League Challenge Seongnam FC Ansan Greeners FC 2017-06-03 12:00:00 FOOTBALL South Korea K-League Challenge FC Anyang Suwon City 2017-06-03 12:30:00 TENNIS French Open Hyeon Chung Kei Nishikori 2017-06-03 12:30:00 TENNIS French Open Andy Murray Juan Martin Del Potro 2017-06-03 12:30:00 TENNIS French Open Fernando Verdasco -

CV Catalog of the Fulbright Finland Foundation Grantees to the U.S

The Fulbright Finland Foundation is an independent not-for-profit organization based in Helsinki, Finland. Its purpose is to promote a wider exchange of knowledge and professional talents through educational contacts between Finland and the United States. The Foundation collaborates with a range of government, foundation, university, and corporate partners on both sides of the Atlantic to design and manage study and research scholarships, leadership development programs, and internationalization services. The Foundation supports the internationalization of education and research in Finland, and helps U.S. and Finnish institutions create linkages. Under its Internationalization Services the Foundation organizes themed study tours to the United States for Finnish higher education experts, runs the highly popular Fulbright Speaker Program, the Fulbright Dialogues series, and the Transatlantic Roundtables, as well as organizes two national Fulbright Seminars every year. The Foundation is funded by the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture, the U.S. Department of State, the Finland-America Educational Trust Fund, private foundations, Finnish and U.S. higher education institutions, alumni of the Fulbright Finland Foundation programs, and private donors. Over 70% of the Foundation’s core funding originates from Finland, and advancement, fundraising, and sponsored grants are a central part of the operation. Please contact the Fulbright Finland Foundation if you wish to contact Since 1949, over 5 900 students, scholars, teachers, artists, and a Fulbright Finland grantee or invite a professionals have participated in our exchange programs – over 3 900 grantee to lecture at your institution. from Finland and 2 000 from the U.S. Representing all fields in the arts, sciences, and the society at large, grantees and alumni are vital to the Fulbright Finland Foundation Foundation’s vision: empowering minds to find global solutions to Hakaniemenranta 6 tomorrow’s challenges. -

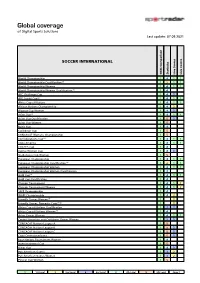

Sportradar Coverage List

Global coverage of Digital Sports Solutions Last update: 07.09.2021 SOCCER INTERNATIONAL Odds Comparison Statistics Live Scores Live Centre World Championship 1 4 1 1 World Championship Qualification (1) 1 2 1 1 World Championship Women 1 4 1 1 World Championship Women Qualification (1) 1 4 AFC Challenge Cup 1 4 3 AFF Suzuki Cup (6) 1 4 1 1 Africa Cup of Nations 1 4 1 1 African Nations Championship 1 4 2 Algarve Cup Women 1 4 3 Asian Cup (6) 1 4 1 1 Asian Cup Qualification 1 5 3 Asian Cup Women 1 5 Baltic Cup 1 4 Caribbean Cup 1 5 CONCACAF Womens Championship 1 5 Confederations Cup (1) 1 4 1 1 Copa America 1 4 1 1 COSAFA Cup 1 4 Cyprus Women Cup 1 4 3 SheBelieves Cup Women 1 5 European Championship 1 4 1 1 European Championship Qualification (1) 1 2 1 1 European Championship Women 1 4 1 1 European Championship Women Qualification 1 4 Gold Cup (6) 1 4 1 1 Gold Cup Qualification 1 4 Olympic Tournament 1 4 1 2 Olympic Tournament Women 1 4 1 2 SAFF Championship 1 4 WAFF Championship 1 4 2 Friendly Games Women (1) 1 2 Friendly Games, Domestic Cups (1) (2) 1 2 Africa Cup of Nations Qualification 1 3 3 Africa Cup of Nations Women (1) 1 4 Asian Games Women 1 4 1 1 Central American and Caribbean Games Women 1 3 3 CONCACAF Nations League A 1 5 CONCACAF Nations League B 1 5 3 CONCACAF Nations League C 1 5 3 Copa Centroamericana 1 5 3 Four Nations Tournament Women 1 4 Intercontinental Cup 1 5 Kings Cup 1 4 3 Pan American Games 1 3 2 Pan American Games Women 1 3 2 Pinatar Cup Women 1 5 1 1st Level 2 2nd Level 3 3rd Level 4 4th Level 5 5th Level Page: -

SG Flensburg- Handewitt, GER

OFFICIAL PROGRAMME VELUX EHF Champions League 2018/2019 Title sponsor Premium sponsor Regional premium sponsors Partners Charity partner 1 2 TEAMWORK, FAIRNESS & RESPECT Nord Stream 2 is a European project that contributes to a secure energy supply for all European countries. Our excellence is the result of effi cient cooperation among a large team of experts from more than 20 countries. Respect for the environment and team spirit are at the core of our values, fuelling our delivery of a sustainable solution to help the EU meet future energy needs and achieve climate goals. powered by Proud supporter of the VELUX EHF Champions League ©EHF/Walch www.nord-stream2.com 3 Table of contents Table of contents Foreword 6 Media contacts 7 Map of participating clubs 8-9 Playing system diagram 10-11 Official informations 13 List of TV stations 15 MOTW - increasing engagement 16 VELUX EHF FINAL4 countdown/anniversary 18-19 VELUX EHF FINAL4 facts & figures 20 Important regulations 23 Facts & Figures 24-27 GROUP A Preview 30-31 Head-to-heads in the EC 32-35 HC Vadar 36-41 PGE Vive Kielce 42-47 Barça Lassa 48-53 HC Meshkov Brest 54-59 Telekom Veszprém HC 60-65 Montpellier HB 66-71 IFK Kristianstad 72-77 Rhein-Neckar Löwen 78-83 GROUP B Preview 84-85 Head-to-heads in the EC 86-89 Paris Saint-Germain Handball 90-95 MOL-Pick Szeged 96-101 SG Flensburg-Handewitt 102-107 Skjern Handbold 108-113 4 Table of contents HC PPD Zagreb 114-119 HC Motor Zaporozhye 120-125 RK Celje Pivovarna Lasko 126-131 HBC Nantes 132-137 GROUP C Preview 138-139 Head-to-heads in the -

Ponuda Za LIVE 02.09.2017

Sheet1 kickoff_time event_id sport competition_name home_name away_name 2017-09-02 10:00:00 1006972 FOOTBALL Hungary U19 League Puskas Academy U19 Videoton FC U19 2017-09-02 10:00:00 1006973 FOOTBALL Hungary U19 League MTK Budapest U19 Ferencvarosi U19 2017-09-02 10:15:00 1006974 FOOTBALL Czech 3. Ligy FC Pisek Benatky Nad Jizerou 2017-09-02 10:15:00 1006975 FOOTBALL Czech 3. Ligy MFK Chrudim Jiskra Domazlice 2017-09-02 10:30:00 1006976 FOOTBALL Czech 3. Ligy FK Litomericko FK Loko Vltavin 2017-09-02 10:30:00 1006979 FOOTBALL Czech U19 League Slovacko U19 Banik Ostrava U19 2017-09-02 11:00:00 1006977 FOOTBALL Czech U19 League Teplice U19 FK Pribram U19 2017-09-02 11:00:00 1006978 FOOTBALL Czech U19 League Slavia Prague U19 Bohemians 1905 U19 2017-09-02 11:00:00 1006980 FOOTBALL Slovakia Youth League AS Trencin U19 FC Spartak Trnava U19 2017-09-02 11:00:00 1006981 FOOTBALL Slovakia Youth League Dunajska Streda U19 Partizan Bardejov U19 2017-09-02 11:00:00 1006982 FOOTBALL Slovakia Youth League MFK Ruzomberok U19 FC Nitra U19 2017-09-02 11:00:00 1006983 FOOTBALL Slovakia Youth League Slovan Bratislava U19 MFK Zemplin Michalovce U19 2017-09-02 11:00:00 1006984 FOOTBALL Slovakia Youth League FC Tatran Presov U19 FK Senica U19 2017-09-02 11:00:00 1006985 FOOTBALL Slovakia Youth League AS Trencin U19 Spartak Trnava U19 2017-09-02 09:30:00 1006986 TENNIS ITF France Florent Bax Lucas Bouquet 2017-09-02 09:30:00 1006987 TENNIS ITF France Yanais Laurent Arthur Reymond 2017-09-02 10:00:00 1006988 TENNIS ITF France Adrian Gabison Hugo Pontico 2017-09-02