Henry Jordan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collecting Lombardi's Dominating Packers

Collecting Lombardi’s Dominating Packers BY DAVID LEE ince Lombardi called Lambeau Field his “pride and joy.” Specifically, the ground itself—the grass and the dirt. V He loved that field because it was his. He controlled everything that happened there. It was the home where Lombardi built one of the greatest sports dynasties of all-time. Fittingly, Lambeau Field was the setting for the 1967 NFL Champion- ship, famously dubbed “The Ice Bowl” before the game even started. Tem- peratures plummeting to 12 degrees below zero blasted Lombardi’s field. Despite his best efforts using an elaborate underground heating system to keep it from freezing, the field provided the perfect rock-hard setting to cap Green Bay’s decade of dominance—a franchise that bullied the NFL for nine seasons. The messy game came down to a goal line play of inches with 16 seconds left, the Packers trailing the Cowboys 17-14. Running backs were slipping on the ice, and time was running out. So, quarterback Bart Starr called his last timeout, and ran to the sideline to tell Lombardi he wanted to run it in himself. It was a risky all-in gamble on third down. “Well then run it, and let’s get the hell out of here,” Starr said Lom- bardi told him. The famous lunge into the endzone gave the Packers their third-straight NFL title (their fifth in the decade) and a second-straight trip to the Super Bowl to face the AFL’s best. It was the end of Lombardi’s historic run as Green Bay’s coach. -

The Ice Bowl: the Cold Truth About Football's Most Unforgettable Game

SPORTS | FOOTBALL $16.95 GRUVER An insightful, bone-chilling replay of pro football’s greatest game. “ ” The Ice Bowl —Gordon Forbes, pro football editor, USA Today It was so cold... THE DAY OF THE ICE BOWL GAME WAS SO COLD, the referees’ whistles wouldn’t work; so cold, the reporters’ coffee froze in the press booth; so cold, fans built small fires in the concrete and metal stands; so cold, TV cables froze and photographers didn’t dare touch the metal of their equipment; so cold, the game was as much about survival as it was Most Unforgettable Game About Football’s The Cold Truth about skill and strategy. ON NEW YEAR’S EVE, 1967, the Dallas Cowboys and the Green Bay Packers met for a classic NFL championship game, played on a frozen field in sub-zero weather. The “Ice Bowl” challenged every skill of these two great teams. Here’s the whole story, based on dozens of interviews with people who were there—on the field and off—told by author Ed Gruver with passion, suspense, wit, and accuracy. The Ice Bowl also details the history of two legendary coaches, Tom Landry and Vince Lombardi, and the philosophies that made them the fiercest of football rivals. Here, too, are the players’ stories of endurance, drive, and strategy. Gruver puts the reader on the field in a game that ended with a play that surprised even those who executed it. Includes diagrams, photos, game and season statistics, and complete Ice Bowl play-by-play Cheers for The Ice Bowl A hundred myths and misconceptions about the Ice Bowl have been answered. -

College All-Star Football Classic, August 2, 1963 • All-Stars 20, Green Bay 17

College All-Star Football Classic, August 2, 1963 • All-Stars 20, Green Bay 17 This moment in pro football history has always captured my imagination. It was the last time the college underdogs ever defeated the pro champs in the long and storied history of the College All-Star Football Classic, previously known as the Chicago Charities College All-Star Game, a series which came to an abrupt end in 1976. As a kid, I remember eagerly awaiting this game, as it signaled the beginning of another pro football season—which somewhat offset the bittersweet knowledge that another summer vacation was quickly coming to an end. Alas, as the era of “big money” pro sports set in, the college all star game quietly became a quaint relic of a more innocent sporting past. Little by little, both the college stars and the teams which had shelled out guaranteed contracts to them began to have second thoughts about participation in an exhibition game in which an injury could slow or even terminate a player’s career development. The 1976 game was played in a torrential downpour, halted in the third quarter with Pittsburgh leading 24-0, and the game—and, indeed, the series—was never resumed. But on that sultry August evening in 1963, with a crowd of 65,000 packing the stands, the idea of athletes putting financial considerations ahead of “the game” wasn’t on anyone’s minds. Those who were in the stands or watching on televiosn were treated to one of the more memorable upsets in football history, as the “college Joes” knocked off the “football pros,” 20-17. -

Granby Mother Kills Her 2 Small Children

r"T ' ' j •'.v> ■ I SATUBDAY, DECEMBER 24, 1960 V‘‘‘ iOanrtifBter E w ttins $?raUt Ifii'J •• t Not (me of the men MW anything funny In the process. No Herald Social Worker About To>m Heard Along Main Street! Just like a woman 7 Some of the men fall in the know-how Pepart- OnMdhday Sought by Town WATBS wlU meet And on Some o) Manehe$ter*§ Side SlreeU,Too ment, too, when it. comes to freeing l^iesdey evening nt the Italian mechanical horses from Ice traps. The town is accepting appUca- The Manchester Evening tiona through Wednesday to fill Amertean ' Chib on Sldrltlge St. <^been a. luncheon guest at the inn. 1 0 :' Welgbtog In win be from 7 to 8 What Are You Gonna Do? It ' So Reverse It a social work^ post with sn an One Herald aubacriber is very Lt. Leander, who is stationed at Herald will-not publish Mon 'Words of advice wer^ voiced nual salary range of 84,004 to YOL. LXXX, NO. 7S (SIXTEEN PAGES) MANCHESTER, CONN„ TUESDAY. DECEMBER 27, 1960 (ChuwUtsg AgvsrttalBg m Fag» 14) PRICE PIVB V-*A red-faced becauee her 10-year-oM the U.S. Navy atatipn .gt Orange, irom one local youngster to an day, the day after Christmas, 14,914 and an allowance for use son got carried away with the Tex., had spent the afterhiibh vla- other as they walked along the Merty Christmas to all. of the worker's own car. Handd S. Crozler will show Christmas spirit. Iting a state park, San Jacinto street in the ijear zero weather. -

GREEN BAY PACKERS EDITION Green Bay Packers Team History

TEACHER ACTIVITY GUIDE GREEN BAY PACKERS EDITION Green Bay Packers Team History The incredible saga of the Green Bay Packers began in August 1919, when the Indian Packing Com- pany agreed to sponsor a local pro football team under the direction of Earl (Curly) Lambeau. In 1921, the Packers were granted a membership in the new National Football League. Today, they rank as the third oldest team in pro football. The long and storied history of the Green Bay team is one of struggle, until comparatively recent, for fi nancial survival off the fi eld and playing stabil- ity on the fi eld. The Packers’ record has been punctuated with periods of both the highest success and the deepest depths of defeat. Many great football players have performed for the Green Bay team but two coaches, Lambeau and Vince Lombardi, rank as the most dominant fi gures in the Packers’ epic. Between the two, Lambeau and Lombardi brought the Packers 11 NFL championships, including two record strings of three straight titles, the fi rst in 1929, 1930 and 1931 and the second in 1965, 1966 and 1967. Those last three championships completed the Packers’ dynasty years in the 1960s, which began with Green Bay also winning NFL championships in 1961 and 1962. During the late 1930s and early 1940s, the Lam- beau-led Packers were annual championship contenders. They won four divisional crowns and NFL titles in 1936, 1939 and 1944. Individually, Lambeau, Lombardi and 20 long-time Packers players are enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Hall of Fame players from the early years include Don Hutson, history’s fi rst great pass receiver, Arnie Herber, Clarke Hinkle, Cal Hubbard, John (Blood) McNally, Mike Michalske and Tony Canadeo. -

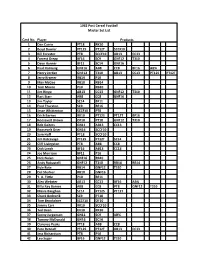

Master Set List

1962 Post Cereal Football Master Set List Card No. Player Products 1 Dan Currie PT18 RK10 2 Boyd Dowler PT12S PT12T SCCF10 3 Bill Forester PT8 SCCF10 AB13 CC13 4 Forrest Gregg BF16 SC9 GNF12 T310 5 Dave Hanner BF11 SC14 GNF16 6 Paul Hornung GNF16 AB8 CC8 BF16 AB¾ 7 Henry Jordan GNF12 T310 AB13 CC13 PT12S PT12T 8 Jerry Kramer RB14 P10 9 Max McGee RB10 RB14 10 Tom Moore P10 RB10 11 Jim Ringo AB13 CC13 GNF12 T310 12 Bart Starr AB8 CC8 GNF16 13 Jim Taylor SC14 BF11 14 Fred Thurston SC9 BF16 15 Jesse Whittenton SCCF10 PT8 16 Erich Barnes RK10 PT12S PT12T BF16 17 Roosevelt Brown OF10 PT18 GNF12 T310 18 Bob Gaiters GN11 AB13 CC13 19 Roosevelt Grier GN16 SCCF10 20 Sam Huff PT18 SCCF10 21 Jim Katcavage PT12S PT12T SC14 22 Cliff Livingston PT8 AB8 CC8 23 Dick Lynch BF16 AB13 CC13 24 Joe Morrison BF11 P10 25 Dick Nolan GNF16 RB10 26 Andy Robustelli GNF12 T310 RB14 RB14 27 Kyle Rote RB14 GNF12 T310 28 Del Shofner RB10 GNF16 29 Y. A. Tittle P10 BF11 30 Alex Webster AB13 CC13 BF16 AB¾ 31 Billy Ray Barnes AB8 CC8 PT8 GNF12 T310 32 Maxie Baughan SC14 PT12S PT12T 33 Chuck Bednarik SC9 PT18 34 Tom Brookshier SCCF10 OF10 35 Jimmy Carr RK10 SCCF10 36 Ted Dean OF10 RK10 37 Sonny Jurgenson GN11 SC9 AB¾ 38 Tommy McDonald GN16 SC14 39 Clarence Peaks PT18 AB8 CC8 40 Pete Retzlaff PT12S PT12T AB13 CC13 41 Jess Richardson PT8 P10 42 Leo Sugar BF16 GNF12 T310 43 Bobby Walston BF11 GNF16 44 Chuck Weber GNF16 RB10 45 Ed Khayat GNF12 T310 RB14 46 Howard Cassady RB14 BF11 47 Gail Cogdill RB10 BF16 48 Jim Gibbons P10 PT8 49 Bill Glass AB13 CC13 PT12S PT12T 50 Alex Karras -

The Packer Fullbacks

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 21, No. 6 (1999) THE PACKER FULLBACKS By Stan Grosshandler To the long time NFL fan, the word fullback conjures up the picture of a powerfully built man crashing into the line head down and knees up. On defense he backed up the line like a stone wall. The name Bronko Nagurski immediately comes to mind as the prototype fullback. The term fullback is about to go the way of the terms as end, blocking back, halfback, and wingback. The usual NFL fullback today is the up man in a two man backfield used as a blocker and occasional pass receiver. The Green Bay Packers have had their share of “real fullbacks”. Their first one of note was Bo Molenda, who played a total of 13 years in the NFL. He started with the Packers in 1928, and then was a member of the three straight championship teams of ‘29,'30, and ‘31. In the Lambeau system the FB stood beside and to the right of the LH or tailback in the Notre Dame box. In a position to receive the ball directly from the center he had to be able to run wide, plunge, spin and hand off, plus pass and receive. Ideal for this job was Clarke Hinkle, who joined the team in 1932 out of Bucknell. Clarke did it all, run, pass, receive, kick both extra points and field goals, and backed up the line. He topped the league in scoring in 1938 (58 points) and led twice in field goals. Hinkle is now in both the Professional and College Halls of Fame. -

News, East Lansing, Michigan I

MICHIGAN STATE t a t e n e w s UNIVERSITY Sunday, November 14, 1965 East Lansing, Michigan WINBYWIN STANDINGS W L MSU13 UCLA 3 MICH. ST. 7 0 Ohio State 5 1 MSU 23 Penn St. 0 Minnesota 4 2 MSU 22 Illinois 12 Purdue 4 2 MSU 24 Michigan 7 Wisconsin 3 3 MSU 32 Ohio State 7 Illinois 3 3 MSU 14 Purdue 10 N ’western 2 4 jbmk -1 m m *mt m MSU 49 N’western 7 Michigan 2 4 MSU 35 Iow a 0 Indiana 1 5 Indiana 13 Io w a 0 7 MSU 27 A-2 Sunday, November 14, 1965 BIG TEN CHAMPIONS Unbeaten ! First Outright r all afternoon by an agj!gravated knee injury, ran for 47 yards and fumbled once. Indiana Throws Scare, This sloppy ball handling was partially due to the cold 39-degrcc weather. , , The Spartans ground out 194 yards rushing to Indiana s 65. Quarterback Frank Stavroff completed 14 of 27 attempted passes But State Rallies,27-13 for 173 yards. End Bill Malinchak haunted Slate’ s defensive lacks all after By RICK PI AN IN noon, catching five passes for 89 yards and one TD. Malinchak State News Staff W riter hauled in a beautiful 46-yard pass late in the second quarter and caught a 10-yard touchdown pass on the next play, with only 46 The Spartan football team claimed its seconds remaining. first undisputed Big Ten championship’here This cut State's early lead to 1 0 -7 and sparked Indiana to go ahead in the third quarter. -

15 Finalists for Hall of Fame Election

For Immediate Release For More Information, Contact January 11, 2006 Joe Horrigan at (330) 456-8207 15 FINALISTS FOR HALL OF FAME ELECTION Troy Aikman, Warren Moon, Thurman Thomas, and Reggie White, four first-year eligible candidates, are among the 15 finalists who will be considered for election to the Pro Football Hall of Fame when the Hall’s Board of Selectors meets in Detroit, Michigan on Saturday, February 4, 2006. Joining the first-year eligible players as finalists, are nine other modern-era players and a coach and player nominated earlier by the Hall of Fame’s Seniors Committee. The Seniors Committee nominees, announced in August 2005, are John Madden and Rayfield Wright. The other modern-era player finalists include defensive ends L.C. Greenwood and Claude Humphrey; linebackers Harry Carson and Derrick Thomas; offensive linemen Russ Grimm, Bob Kuechenberg and Gary Zimmerman; and wide receivers Michael Irvin and Art Monk. To be elected, a finalist must receive a minimum positive vote of 80 percent. Listed alphabetically, the 15 finalists with their positions, teams, and years follow: Troy Aikman – Quarterback – 1989–2000 Dallas Cowboys Harry Carson – Linebacker – 1976-1988 New York Giants L.C. Greenwood – Defensive End – 1969-1981 Pittsburgh Steelers Russ Grimm – Guard – 1981-1991 Washington Redskins Claude Humphrey – Defensive End – 1968-1978 Atlanta Falcons, 1979-1981 Philadelphia Eagles (injured reserve – 1975) Michael Irvin – Wide Receiver – 1988-1999 Dallas Cowboys Bob Kuechenberg – Guard – 1970-1984 Miami Dolphins -

Gophers Drub Northwestern

THE SUNDAY STAR, Washington, D. C,** SUNDAY. OCTOBER 11, 19*3 C-3 Gophers Drub Northwestern; Indiana Shades Marquette, 21-20 Giel and McNamara Score in Last Minute Brigman Leads Georgia Tech I illi * Hb Set Terrific Pace Wm i .wa hi jb bos Ends Hoosier Streak To 27-13 Victory Oyer Tulane By the Associated Press 6-0, on Fullback Ronnie Kent's ji\jbß Kill NEW ORLEANS. Oct. 10.—j l»yard scoring buck in the open- In Minnesota Win Os Seven Defeats Quarterback Bill Brigman re- ! ing quarter. •yth* Associated Press By tha Associated Press turned today from one-platoon Brigman, Tech’s regular quar- / BLOOMINGTON, Ind.. Oct. obscurity to throw two touch- terback last season, played sec- EVANSTON, 111., Oct. 10.— S , '9P JM seven-game down passes and lead unbeaten string to Mitchell Minnesota, with Paul Giel and 10.—Indiana broke a ond Wade this losing streak today with a 21-20 Georgia Tech to a 27-13 victory season, although drawing the Bob McNamara providing a ter- victory over Marquette which over a gallant but out-manned i token starting role. rific one-two punch, jarred came in the las* 40 seconds on Tulane team. Brigman Takes Over. Northwestern into a 30-13 Big Hr 'MM nBS WKtBKHBBBMk «L r Dave Rogers’ touchdown plunge After a slow, fumbling start, I Brigman took over after Tech Ten football defeat today. It ¦ and Florian Helsinki’s third ex- Tech gathered speed under the scored its first touchdown on tra-point kick. | lash of Brigman’s accurate Fullback Glenn Turner’s diving was the Wildcats’ first loss in throwing '9Hk| i, v^^^^^hhhh||^^^hphhhhh^jhh^^^^h^hhh9^m% The Hoosiers. -

2020 Packers Activity Guide

PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME TEACHER ACTIVITY GUIDE 2020-2021 EDITIOn quarterback Brett Favre - Hall of fame class of 2016 GREEn BAY PACKERS Team History The incredible saga of the Green Bay Packers began in August 1919, when the Indian Packing Company agreed to sponsor a local pro football team under the direction of Earl (Curly) Lambeau. In 1921, the Packers were granted a membership in the new National Football League. Today, they rank as the third oldest team in pro football. The long and storied history of the Green Bay team is one of struggle, until comparatively recent, for financial survival off the field and playing stability on the field. The Packers’ record has been punctuated with periods of both the highest success and the deepest depths of defeat. Many great football players have performed for the Green Bay team but two coaches, Lambeau and Vince Lombardi, rank as the most dominant figures in the Packers’ epic. Between the two, Lambeau and Lombardi brought the Packers 11 NFL championships, including two record strings of three straight titles, the first in 1929, 1930 and 1931 and the second in 1965, 1966 and 1967. Those last three championships completed the Packers’ dynasty years in the 1960s, which began with Green Bay also winning NFL championships in 1961 and 1962. During the late 1930s and early 1940s, the Lambeau-led Packers were annual championship contenders. They won four divisional crowns and 3 NFL titles. Individually, Lambeau, Lombardi and 24 long-time Packers greats are enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. -

Pro Football Hall of Fame

PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME The Professional Football Hall Between four and seven new MARCUS ALLEN CLIFF BATTLES of Fame is located in Canton, members are elected each Running back. 6-2, 210. Born Halfback. 6-1, 195. Born in Ohio, site of the organizational year. An affirmative vote of in San Diego, California, Akron, Ohio, May 1, 1910. meeting on September 17, approximately 80 percent is March 26, 1960. Southern Died April 28, 1981. West Vir- 1920, from which the National needed for election. California. Inducted in 2003. ginia Wesleyan. Inducted in Football League evolved. The Any fan may nominate any 1982-1992 Los Angeles 1968. 1932 Boston Braves, NFL recognized Canton as the eligible player or contributor Raiders, 1993-1997 Kansas 1933-36 Boston Redskins, Hall of Fame site on April 27, simply by writing to the Pro City Chiefs. Highlights: First 1937 Washington Redskins. 1961. Canton area individuals, Football Hall of Fame. Players player in NFL history to tally High lights: NFL rushing foundations, and companies and coaches must have last 10,000 rushing yards and champion 1932, 1937. First to donated almost $400,000 in played or coached at least five 5,000 receiving yards. MVP, gain more than 200 yards in a cash and services to provide years before he is eligible. Super Bowl XVIII. game, 1933. funds for the construction of Contributors (administrators, the original two-building com- owners, et al.) may be elected LANCE ALWORTH SAMMY BAUGH plex, which was dedicated on while they are still active. Wide receiver. 6-0, 184. Born Quarterback.