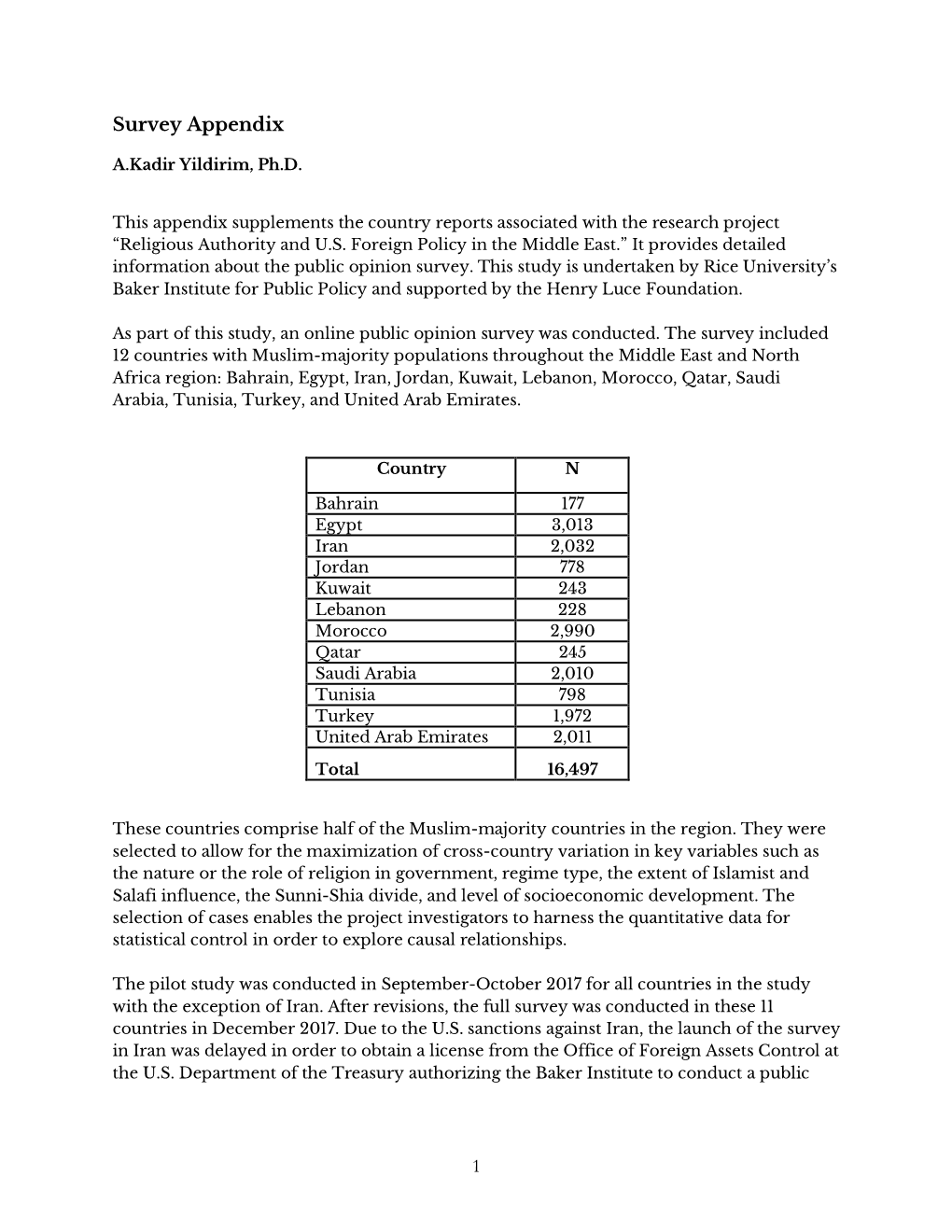

Islam and Authority in the Middle East — Survey Appendix

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dialogue the Only Way to Solve Region's Crises: Amir

BUSINESS | Page 1 Salem Khalaf al-Mannai appointed group CEO of Qatar Insurance Group published in QATAR since 1978 MONDAY Vol. XXXX No. 11426 January 13, 2020 Jumada I 18, 1441 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Dialogue the only way to Amir off ers condolences solve region’s crises: Amir to Sultan Haitham on the death of Sultan Qaboos zAmir holds talks with senior Iranian leaders including Khamenei and Rouhani zQatar, Iran agree to enhance trade and tourism exchange His Highness the Amir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani meeting the Supreme Leader of Iran, Ali Khamenei, in Tehran yesterday. is Highness the Amir Sheikh Tamim bin Earlier in the day, His Highness the Amir arrived Hamad al-Thani off ered condolences in Muscat, accompanied by an offi cial delegation. QNA ciating Iran’s position after the between the two countries. ther escalation and peacefully Hto Sultan Haitham bin Tariq al-Said of He was welcomed at the Private Sultani Airport by Tehran blockade of Qatar and thanked The Iranian president empha- settling differences in a way Oman on the death of Sultan Qaboos bin Said bin Minister of State Sayyid Fatik bin Fahar al-Said, Iran for providing all the facilities sised the importance of the secu- that contributes to achieving Taimur, at Al Alam Palace in Muscat yesterday Governor of Muscat Sayyid Saud bin Hilal al-Bu- to Qatar and the Qatari people by rity of the region, especially the security, peace and stability in morning. saidi, Qatar’s ambassador to Oman Sheikh Jassim ialogue is the only way to immediately opening its airspace security of waterways in the Gulf, the region and the world. -

Shia-Islamist Political Actors in Iraq Who Are They and What Do They Want? Søren Schmidt DIIS REPORT 2008:3 DIIS REPORT

DIIS REPORT 2008:3 SHIA-IsLAMIST POLITICAL ACTORS IN IRAQ WHO Are THEY AND WHAT do THEY WANT? Søren Schmidt DIIS REPORT 2008:3 DIIS REPORT DIIS · DANISH INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES 1 DIIS REPORT 2008:3 © Copenhagen 2008 Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS Strandgade 56, DK -1401 Copenhagen, Denmark Ph: +45 32 69 87 87 Fax: +45 32 69 87 00 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.diis.dk Cover Design: Carsten Schiøler Layout: mgc design, Jens Landorph Printed in Denmark by Vesterkopi AS ISBN: 978-87-7605-247-8 Price: DKK 50.00 (VAT included) DIIS publications can be downloaded free of charge from www.diis.dk Hardcopies can be ordered at www.diis.dk. 2 DIIS REPORT 2008:3 Contents Abstract 4 1. Introduction 5 2. The Politicisation of Shia-Islam 7 2.1 Introduction 7 2.2 The History of Shia-Islamism in Iraq 8 3. Contemporary Shia-Islamist political actors 15 3.1 Ali Husseini Sistani 15 3.2 The Da’wa Party 21 3.3 SCIRI 24 3.4 Moqtada al-Sadr 29 4. Conclusion: Conflict or Cooperation? 33 Bibliography 35 3 DIIS REPORT 2008:3 Abstract The demise of the regime of Saddam Hussein in Iraq in 2003 was an important wa- tershed in Iraqi political history. Iraq had been governed by groups which belonged to the Arab Sunni minority since the Iraqi state emerged out of the former Otto- man Empire in 1921. More recently, new political actors are in the ascendancy, rep- resenting the Kurdish minority and the Shia majority in Iraq. -

The Migration of Indians to Eastern Africa: a Case Study of the Ismaili Community, 1866-1966

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2019 The Migration of Indians to Eastern Africa: A Case Study of the Ismaili Community, 1866-1966 Azizeddin Tejpar University of Central Florida Part of the African History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Tejpar, Azizeddin, "The Migration of Indians to Eastern Africa: A Case Study of the Ismaili Community, 1866-1966" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 6324. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/6324 THE MIGRATION OF INDIANS TO EASTERN AFRICA: A CASE STUDY OF THE ISMAILI COMMUNITY, 1866-1966 by AZIZEDDIN TEJPAR B.A. Binghamton University 1971 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2019 Major Professor: Yovanna Pineda © 2019 Azizeddin Tejpar ii ABSTRACT Much of the Ismaili settlement in Eastern Africa, together with several other immigrant communities of Indian origin, took place in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth centuries. This thesis argues that the primary mover of the migration were the edicts, or Farmans, of the Ismaili spiritual leader. They were instrumental in motivating Ismailis to go to East Africa. -

13 May 2021, Rome to His Majesty King Hamad Bin Isa Al Khalifa Of

13 May 2021, Rome To His Majesty King Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa of Bahrain, We, Members of the Italian Parliament, are writing to you today to express our deep concerns over the fate of the prisoners of conscience and the human rights defenders currently held in the prisons of the Kingdom of Bahrain. We are aware that not only are these prisoners subjected to unjust punishment and ill-treatment, but that they are also experiencing a disproportionately high risk of illness, as they are deprived of medical attention and personal protective equipment necessary to protect against COVID-19. This situation is great cause for concern, since it violates the values of freedom, dignity, and respect that Italy and the rest of the international community hold dear. Moreover, it does not respect the many international treaties that the Kingdom of Bahrain has signed which aim to defend human freedom, dignity, and safety. These treaties further safeguard an individual’s right to freedom of expression and freedom of speech, and include the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), the Convention Against Torture (CAT), and the Arab Charter on Human Rights (ACHR). As you are certainly aware, on 11th March 2021, the EU Parliament passed a resolution that addresses the cases of the prisoners of conscience and human rights defenders who are currently serving their prison sentences. For example, Hassan Mushaima, the leader of the political opposition, the former Secretary-General of the al-Haq Movement for Liberty and Democracy, and co-Founder and former Vice President of al-Wefaq National Islamic Society, has been imprisoned since 2011 because of his political opposition. -

The UK's Relations with Saudi Arabia and Bahrain

House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee The UK’s relations with Saudi Arabia and Bahrain Fifth Report of Session 2013–14 Volume II Additional written evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be published 12 November 2013 Published on 22 November 2013 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited The Foreign Affairs Committee The Foreign Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and its associated agencies. Current membership Rt Hon Richard Ottaway (Conservative, Croydon South) (Chair) Mr John Baron (Conservative, Basildon and Billericay) Rt Hon Sir Menzies Campbell (Liberal Democrat, North East Fife) Rt Hon Ann Clwyd (Labour, Cynon Valley) Mike Gapes (Labour/Co-op, Ilford South) Mark Hendrick (Labour/Co-op, Preston) Sandra Osborne (Ayr, Carrick and Cumnock) Andrew Rosindell (Conservative, Romford) Mr Frank Roy (Labour, Motherwell and Wishaw) Rt Hon Sir John Stanley (Conservative, Tonbridge and Malling) Rory Stewart (Conservative, Penrith and The Border) The following Members were also members of the Committee during the parliament: Rt Hon Bob Ainsworth (Labour, Coventry North East) Emma Reynolds (Labour, Wolverhampton North East) Mr Dave Watts (Labour, St Helens North) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including news items) are on the internet at www.parliament.uk/facom. -

Political Repression in Sudan

Sudan Page 1 of 243 BEHIND THE RED LINE Political Repression in Sudan Human Rights Watch/Africa Human Rights Watch Copyright © May 1996 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 96-75962 ISBN 1-56432-164-9 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report was researched and written by Human Rights Watch Counsel Jemera Rone. Human Rights Watch Leonard H. Sandler Fellow Brian Owsley also conducted research with Ms. Rone during a mission to Khartoum, Sudan, from May 1-June 13, 1995, at the invitation of the Sudanese government. Interviews in Khartoum with nongovernment people and agencies were conducted in private, as agreed with the government before the mission began. Private individuals and groups requested anonymity because of fear of government reprisals. Interviews in Juba, the largest town in the south, were not private and were controlled by Sudan Security, which terminated the visit prematurely. Other interviews were conducted in the United States, Cairo, London and elsewhere after the end of the mission. Ms. Rone conducted further research in Kenya and southern Sudan from March 5-20, 1995. The report was edited by Deputy Program Director Michael McClintock and Human Rights Watch/Africa Executive Director Peter Takirambudde. Acting Counsel Dinah PoKempner reviewed sections of the manuscript and Associate Kerry McArthur provided production assistance. This report could not have been written without the assistance of many Sudanese whose names cannot be disclosed. CONTENTS -

Shiism: What Students Need to Know - FPRI Page 1 of 4

Shiism: What Students Need to Know - FPRI Page 1 of 4 Footnotes Search The Newsletter of FPRI’s Wachman Center Shiism: What Students Need to Know By John Calvert May 2010 Vol. 15, No. 2 John Calvert is Fr. Henry W. Casper SJ associate professor of history at Creighton University in Omaha, Nebraska. This essay is excerpted from his book “Divisions within Islam,” part of a 10-volume series for middle and high school students on the World of Islam, put out by Mason Crest Publishers in cooperation with FPRI. Also see his “Sunni Islam: What Students Need to Know.” For information about the series, or to order, visit: http://www.masoncrest.com/series_view.php?seriesID=90 Shiism is the second-largest denomination of Islam, after Sunni Islam. Today, the Shia comprise about 10 percent of the total population of Muslims in the world. The most important group within the Shia is the “Twelvers,” so called for the 12 Imams, or leaders, they venerate. The largest concentrations of Shia Muslims are found in the Islamic Republic of Iran, where they make up 89 percent of the country’s total population; Iraq, where they comprise 63 percent of the country’s total; and Lebanon, where they are 41 percent of the total population. Numerically significant Twelver Shia communities also exist in the Arab Gulf (Bahrain, Kuwait, and northeastern Saudi Arabia), Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India. Subgroups within the Shia include the Zaydis, who exist mostly in Yemen; and the Ismailis, who live mainly in India, in East Africa and in scattered communities in North America and Western Europe. -

Patterns of Torture in Bahrain: Perpetrators Must Face Justice

Patterns of Torture in Bahrain: Perpetrators must Face Justice A Report by the Gulf Centre for Human Rights (GCHR) March 2021 Patterns of Torture in Bahrain: Perpetrators must Face Justice I. Executive Summary 3 II. Methodology 4 III. Introduction 5 1. Patterns of Torture 6 1.1 The Prevalence of Torture in the Bahraini Justice System and Extraction of Confessions by Torture 6 1.2 Gross Violations of Fair Trial Rights and Due Process: The Admissibility of Confessions Extracted by Torture in Criminal Proceedings 10 1.3 The Use of Torture and its Chilling Effect on Exercising the Rights to Freedom of Expression, Assembly and Association 11 1.4 Torture and Travel Bans in Reprisal against Human Rights Defenders who Interact with International Human Rights Mechanisms 12 2. Ending the Culture of Impunity: Ensuring that Perpetrators of Torture are Held Accountable 14 2.1 Tackling the Culture of Impunity within Bahrain 14 2.2 Ensuring International Accountability by Moving Away from a Culture of Complicity in the International Community 15 3. Conclusion 20 4. Recommendations 21 4.1 Recommendations to the Government of Bahrain 21 4.2 Recommendations to the International Community 21 2 Patterns of Torture in Bahrain: Perpetrators must Face Justice I. Executive Summary This report provides a comprehensive overview of the specific ways and means by which torture is perpetrated in Bahrain, with a particular focus on the period since the 2011 popular movement and the violent crackdown that followed. The report documents the widespread use of forms of -

Report on Bahrain's Attorney General

Report on Bahrain’s Attorney General Dr. Ali bin Fadhel Al‐ Buainain and his position in the International Association of Prosecutors . Report on Bahrain’s Attorney General Dr. Ali bin Fadhel Al‐ Buainain and his position in the International Association of Prosecutors Copyright © 2012 Ceartas All rights reserved Publication date: April 2013 Ceartas 7 Red Cow Lane, Smithfield, Dublin 7, Ireland Company registration number No: 521220 Ceartas‐Irish Lawyers for Human Rights is an independent non‐profit organisation that seeks to promote and realise human rights standards internationally through innovative legal actions. We provide a platform to explore existing and alternative legal strategies by bringing together a range of legal professionals through our pro‐bono register and expert groups. Ceartas primarily aims to effect human rights change in other countries through the use of Irish, regional and international mechanisms with the view to promoting accountability on international human rights issues. For more information visit www.ceartaslaw.org T A B L E O F C O N T E N TS . Executive summary 1. Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………………….1 2. Background to recent changes in the criminal justice system of Bahrain...................2 3. Overview of the International Association of Prosecutors…….....……..…………………3 4. Prosecution for the rights of expression and assembly…………...………..……………….4 5. Adherence to fair procedures and due process………….…………...…………………….…10 6. Investigating and prosecuting on matters of torture…........……..…..…………………....13 7. Findings……………………..….……………….……………………………………………………………..17 8. Recommendations……………………………………………………………………………………….....22 Annexes . E X E C U T I V E SU M M A R Y This report, using evidence widely available, examines the role of Dr. Ali bin Fadhel Al‐ Buainain, Attorney General of Bahrain, and his suitability as an Executive Committee member of the International Association of Prosecutors. -

Shia-Muslims-Published-By-IMAM.Pdf

Shia Muslims Shia Muslims Our Identity, Our Vision, and the Way Forward Sayyid M. B. Kashmiri Imam Mahdi Association of Marjaeya, Dearborn, MI 48124, www.imam-us.org © 2017, 2018. by Imam Mahdi Association of Marjaeya All rights reserved. Published 2018. Printed in the United States of America ISBN-13: 978-0-9982544-9-4 Second Edition No part of this publication may be reproduced without permission from I.M.A.M., except in cases of fair use. Brief quotations, especially for the purpose of propagating Islamic teachings, are allowed. Contents Preface ............................................................................... vii Our Identity ......................................................................... 1 3 .................................. (التوحيد :Monotheism (Tawhid, Arabic 4 .................................... (المعاد :The Hereafter (Ma’ad, Arabic 7 ....................................................... (العدل :Justice (Adl, Arabic 11 ........................... ( النبوة :Prophethood (Nubuwwah, Arabic 15 ................................. (اﻹمامة :Leadership (Imamate, Arabic Our Vision ......................................................................... 25 Acquiring Moral Attributes ................................................. 27 The Age of Justice ................................................................. 29 The Way Forward .................................................................. 33 Leadership in the Absence of Imam al-Mahdi ........................ 35 Preparation for the Age of the Return -

The Prospects of Political Islam in a Troubled Region Islamists and Post-Arab Spring Challenges

The Prospects of Political Islam in a Troubled Region Islamists and Post-Arab Spring Challenges Editor Dr. Mohammed Abu Rumman The Prospects of Political Islam in a Troubled Region Islamists and Post-Arab Spring Challenges Editor Dr. Mohammed Abu Rumman 1 The Hashemite Kingdom Of Jordan The Deposit Number at The National Library (2018/2/529) 277 AbuRumman, Mohammad Suliman The Prospects Of Political Islam In A Troubled Region / Moham- mad Suliman Abu Rumman; Translated by William Joseph Ward. – Am- man: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, 2018 (178) p. Deposit No.: 2018/2/529 Descriptors: /Politics//Islam/ يتحمل المؤلف كامل المسؤولية القانونية عن محتوى مصنفه وﻻ ّيعبر هذا المصنف عن رأي دائرة المكتبة الوطنية أو أي جهة حكومية أخرى. Published in 2018 by Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Jordan & Iraq FES Jordan & Iraq P.O. Box 941876 Amman 11194 Jordan Email: [email protected] Website:www.fes-jordan.org Not for sale © FES Jordan & Iraq All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted, reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means without prior written permission from the publishers. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are solely those of the original author. They do not necessarily represent those of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung or the editor. Translation: William Joseph Ward Cover and Lay-out: Mua’th Al Saied Printing: Economic Press ISBN: 978-9957-484-80-4 2 The Prospects of Political Islam in a Troubled Region Islamists and Post-Arab Spring Challenges Contributed Authors Dr. Mohammed Abu Rumman Dr. Khalil Anani Dr. Neven Bondokji Hassan Abu Hanieh Dr. -

Public Opinion on the Religious Authority of the Moroccan King

ISSUE BRIEF 05.14.19 Public Opinion on the Religious Authority of the Moroccan King Annelle Sheline, Ph.D., Zwan Postdoctoral Fellow, Rice University’s Baker Institute rationalism, and the Sufi tradition of Imam INTRODUCTION Junayd.1 According to the government Morocco has worked to establish itself as narrative, these constitute a specifically a bulwark against religious extremism Moroccan form of Islam that inoculates the in recent years: the government trains kingdom against extremism. One of the women to serve as religious guides, or most significant components of Moroccan “mourchidates,” to counteract violent Islam is the figure of the Commander of the messaging; since launching in 2015, the Faithful or “Amir al-Mu’mineen,” a status Imam Training Center has received hundreds held by the Moroccan king, who claims of imams from Europe and Africa to study descent from the Prophet Mohammad. The Moroccan Islam; in 2016, in response to figure of the Commander of the Faithful is ISIS atrocities against Yazidis, the king of unique to Morocco; no other contemporary 2 Morocco gathered esteemed Muslim leaders Muslim head of state holds a similar title. to release The Marrakesh Declaration on Morocco’s efforts to counteract the rights that Islam guarantees to non- extremist forms of Islam, and military Muslims. Such initiatives have contributed partnership with the U.S. and EU, have to Morocco’s international reputation as a cemented the kingdom’s reputation as a bastion of religious tolerance under state key ally in combatting terrorism. Yet while stewardship of religion. Mohammed VI’s role as a religious figure But to what extent do Moroccans view is frequently noted in media coverage, such state leadership in religion favorably, few studies have sought to evaluate or see head of state King Mohammed VI as whether Moroccan citizens trust their king To what extent do 3 a source of religious authority? According as an authority on religious matters.