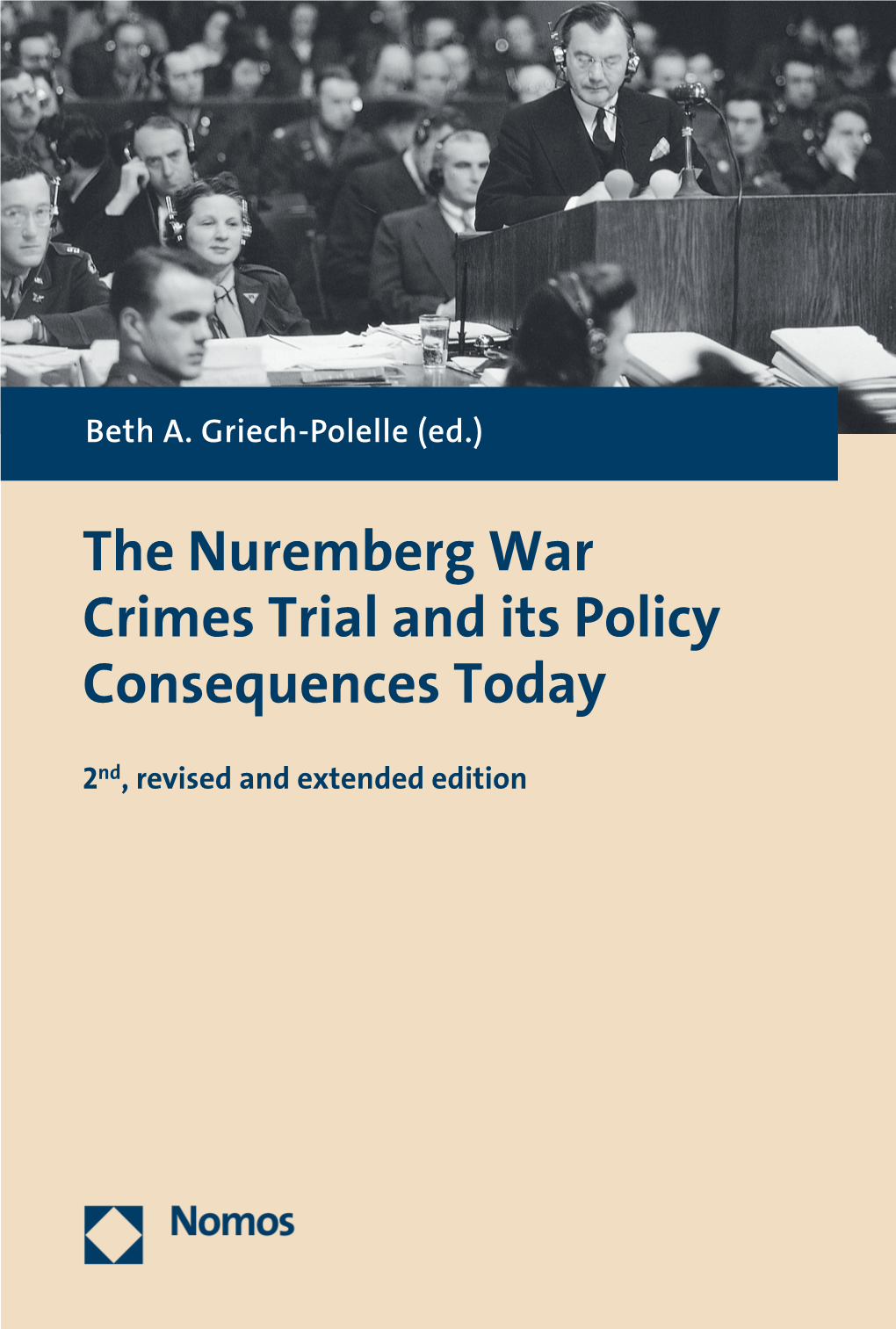

The Nuremberg War Crimes Trial and Its Policy Consequences Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landeszentrale Für Politische Bildung Baden-Württemberg, Director: Lothar Frick 6Th Fully Revised Edition, Stuttgart 2008

BADEN-WÜRTTEMBERG A Portrait of the German Southwest 6th fully revised edition 2008 Publishing details Reinhold Weber and Iris Häuser (editors): Baden-Württemberg – A Portrait of the German Southwest, published by the Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Baden-Württemberg, Director: Lothar Frick 6th fully revised edition, Stuttgart 2008. Stafflenbergstraße 38 Co-authors: 70184 Stuttgart Hans-Georg Wehling www.lpb-bw.de Dorothea Urban Please send orders to: Konrad Pflug Fax: +49 (0)711 / 164099-77 Oliver Turecek [email protected] Editorial deadline: 1 July, 2008 Design: Studio für Mediendesign, Rottenburg am Neckar, Many thanks to: www.8421medien.de Printed by: PFITZER Druck und Medien e. K., Renningen, www.pfitzer.de Landesvermessungsamt Title photo: Manfred Grohe, Kirchentellinsfurt Baden-Württemberg Translation: proverb oHG, Stuttgart, www.proverb.de EDITORIAL Baden-Württemberg is an international state – The publication is intended for a broad pub- in many respects: it has mutual political, lic: schoolchildren, trainees and students, em- economic and cultural ties to various regions ployed persons, people involved in society and around the world. Millions of guests visit our politics, visitors and guests to our state – in state every year – schoolchildren, students, short, for anyone interested in Baden-Würt- businessmen, scientists, journalists and numer- temberg looking for concise, reliable informa- ous tourists. A key job of the State Agency for tion on the southwest of Germany. Civic Education (Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Baden-Württemberg, LpB) is to inform Our thanks go out to everyone who has made people about the history of as well as the poli- a special contribution to ensuring that this tics and society in Baden-Württemberg. -

Defending the Emergence of the Superior Orders Defense in the Contemporary Context

Goettingen Journal of International Law 2 (2010) 3, 871-892 Defending the Emergence of the Superior Orders Defense in the Contemporary Context Jessica Liang Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................ 872 A. Introduction .......................................................................................... 872 B. Superior Orders and the Soldier‘s Dilemma ........................................ 872 C. A Brief History of the Superior Orders Defense under International Law ............................................................................................. 874 D. Alternative Degrees of Attributing Criminal Responsibility: Finding the Right Solution to the Soldier‘s Dilemma ..................................... 878 I. Absolute Defense ................................................................................. 878 II. Absolute Liability................................................................................. 880 III.Conditional Liability ............................................................................ 881 1. Manifest Illegality ..................................................................... 881 2. A Reasonableness Standard ...................................................... 885 E. Frontiers of the Defense: Obedience to Civilian Orders? .................... 889 I. Operation under the Rome Statute ....................................................... 889 II. How far should the Defense of Superior Orders -

Genocide and Belonging: Processes of Imagining Communities

GENOCIDE AND BELONGING: PROCESSES OF IMAGINING COMMUNITIES ADENO ADDIS* ABSTRACT Genocide is often referred to as “the crime of crimes.” It is a crime that is very high on the nastiness scale. The purpose of the genocidaire is of course to destroy a community—a community that he regards as a threat to his own community, whether the threat is perceived as physical, economic or cultural. The way this takes place and the complicity of law in this process has been extensively explored by scholars. But the process of destroying a community is perversely often simultaneously an “exercise in community build- ing,” a process through which intra-communal bonds and belong- ing are sought to be strengthened. This aspect of genocide has been entirely neglected by scholars, especially the role of law in that pro- cess. This article makes and defends two claims about communities and belonging in relation to genocide. First, it argues that as per- verse as it sounds, genocide is in fact an exercise in community building and law is highly implicated in that process. It defends the thesis with arguments that are conceptual as well as empirical. The second, and more hopeful, claim is that the international response * W. R. Irby Chair and W. Ray Forrester Professor of Public and Constitutional Law, Tulane University School of Law. Previous drafts of the paper were presented at an international conference at the Guanghua Law School of Zhejiang University (China) and at Tulane Law School faculty symposium. I thank participants at those meetings for the many helpful questions and comments. -

Open Slate Thesis.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENTS OF GERMANIC AND SLAVIC LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES AND GLOBAL AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES In Vielfalt geeint: The foundations of modern Europe through the example of post-war Freiburg, 1945-1951 ABIGAIL SLATE SPRING 2021 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in German, French and Francophone Studies, Global and International Studies, and Linguistics with interdisciplinary honors in German and Global and International Studies Reviewed and approved* by the following: Bettina Brandt Teaching Professor of German and Jewish Studies Thesis Supervisor and Honors Advisor in German Jonathan Abel Associate Professor of Comparative Literature and Asian Studies Honors Advisor in Global and International Studies Samuel Frederick Associate Professor of German Faculty Reader in German * Electronic approvals are on file. i ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis, “In Vielfalt geeint: The foundations of modern Europe through the example of post-war Freiburg, 1945-1951,” is twofold. First, after introducing the southwestern German city of Freiburg im Breisgau, I will examine some of the reconstruction activities that occurred there within the six-year period following the end of World War II. Specifically, I will discuss the work of the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC, a faith- based Quaker service organization) and of the French military government in occupied Freiburg, with special attention to efforts that promoted cultural reconciliation. Second, using Freiburg as a case study of the larger-scale post-war changes that were occurring across Europe, I will explain how the exchange of ideologies, languages, and cultural practices within this period helped to lay the foundations for the modern, peaceful, and unified Europe we know today. -

THE WESTERN ALLIES' RECONSTRUCTION of GERMANY THROUGH SPORT, 1944-1952 by Heather L. Dichter a Thesis Subm

SPORTING DEMOCRACY: THE WESTERN ALLIES’ RECONSTRUCTION OF GERMANY THROUGH SPORT, 1944-1952 by Heather L. Dichter A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Department of History, University of Toronto © Copyright by Heather L. Dichter, 2008 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-57981-7 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-57981-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Excerpt from Elizabeth Borgwardt, the Nuremberg Idea: “Thinking Humanity” in History, Law & Politics, Under Contract with Alfred A

Excerpt from Elizabeth Borgwardt, The Nuremberg Idea: “Thinking Humanity” in History, Law & Politics, under contract with Alfred A. Knopf. DRAFT of 10/24/16; please do not cite or quote without author’s permission Human Rights Workshop, Schell Center for International Human Rights, Yale Law School November 3, 2016, 12:10 to 1:45 pm, Faculty Lounge Author’s Note: Thank you in advance for any attention you may be able to offer to this chapter in progress, which is approximately 44 double-spaced pages of text. If time is short I recommend starting with the final section, pp. 30-42. I look forward to learning from your reactions and suggestions. Chapter Abstract: This history aims to show how the 1945-49 series of trials in the Nuremberg Palace of Justice distilled the modern idea of “crimes against humanity,” and in the process established the groundwork for the modern international human rights regime. Over the course of the World War II era, a 19th century version of crimes against humanity, which might be rendered more precisely in German as Verbrechen gegen die Menschlichkeit (crimes against “humane-ness”), competed with and was ultimately co-opted by a mid-20th- century conception, translated as Verbrechen gegen die Menschheit (crimes against “human- kind”). Crimes against humaneness – which Hannah Arendt dismissed as “crimes against kindness” – were in effect transgressions against traditional ideas of knightly chivalry, that is, transgressions against the humanity of the perpetrators. Crimes against humankind – the Menschheit version -- by contrast, focused equally on the humanity of victims. Such extreme atrocities most notably denied and attacked the humanity of individual victims (by denying their human rights, or in Arendt’s iconic phrasing, their “right to have rights”). -

The Relationship Between International Humanitarian Law and the International Criminal Tribunals Hortensia D

Volume 88 Number 861 March 2006 The relationship between international humanitarian law and the international criminal tribunals Hortensia D. T. Gutierrez Posse Hortensia D. T. Gutierrez Posse is Professor of Public International Law, University of Buenos Aires Abstract International humanitarian law is the branch of customary and treaty-based international positive law whose purposes are to limit the methods and means of warfare and to protect the victims of armed conflicts. Grave breaches of its rules constitute war crimes for which individuals may be held directly accountable and which it is up to sovereign states to prosecute. However, should a state not wish to, or not be in a position to, prosecute, the crimes can be tried by international criminal tribunals instituted by treaty or by binding decision of the United Nations Security Council. This brief description of the current legal and political situation reflects the state of the law at the dawn of the twenty-first century. It does not, however, describe the work of a single day or the fruit of a single endeavour. Quite the contrary, it is the outcome of the international community’s growing awareness, in the face of the horrors of war and the indescribable suffering inflicted on humanity throughout the ages, that there must be limits to violence and that those limits must be established by the law and those responsible punished so as to discourage future perpetrators from exceeding them. Short historical overview International humanitarian law has played a decisive role in this development, as both the laws and customs of war and the rules for the protection of victims fall 65 H. -

Nuremberg and Group Prosecution

Washington University Law Review Volume 1951 Issue 3 1951 Nuremberg and Group Prosecution Richard Arens University of Buffalo Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Legal History Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation Richard Arens, Nuremberg and Group Prosecution, 1951 WASH. U. L. Q. 329 (1951). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol1951/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NUREMBERG AND GROUP PROSECUTION* RICHARD ARENSt INTRODUCTION The trial of the Nazi war criminals at Nuremberg for crimes against peace, war crimes and crimes against humanity involved not only the indictment of individual defendants but also the indictment of the major Nazi organizations. 1 An aspect almost completely ignored in the welter of allega- gations concerning the ex post facto basis of the Nuremberg prosecutions2 is that concerning the infliction of collective or group sanctions through adjudication of group criminality. The question touching on the use of such sanctions for the maintenance of public order has become particularly acute in recent years in democratic society faced with the threat of global violence. An ominous resort to group or collective deprivations was highlighted in the Western world during World War II by deportation of West Coast Japanese-Americans to "relocation centers" in the name of security? A subsequent resort to the infliction of such deprivations has become apparent in the * This is the second of two studies on war crimes prosecutions prepared for the Quarterly by Professor Arens. -

Nuremberg Academy Annual Report 2018

Annual Report International Nuremberg Principles Academy 1 Imprint The Annual Report 2018 has been Executive Board: published by the International Klaus Rackwitz (Director), Nuremberg Principles Academy. Dr. Viviane Dittrich (Deputy Director) It is available in English, German Edited by: and French and can be ordered Evelyn Müller at [email protected] Layout: or be downloaded on the website Martin Küchle Kommunikationsdesign www.nurembergacademy.org. Photos: Egidienplatz 23 International Nuremberg Principles Academy 90403 Nuremberg, Germany p. 9 Strathmore University, p. 20 Wayamo T + 49 (0) 911.231.10379 Foundation F + 49 (0) 911.231.14020 Printed by: [email protected] Druckwerk oHG Table of Contents 2 Foreword 5 The International Nuremberg Principles Academy 7 A Forum for Dialogue 8 • Events 14 • Network and Cooperation 19 Capacity Building 25 Research 29 Publications and Resources 32 Communications 34 Organization 37 Partners and Sponsors We proudly present the second edition of the Annual Report of the International Nuremberg Principles Academy. It reflects the activities and the achieve ments of the Nuremberg Academy throughout the year of 2018. It was another year of growth for the Nu Foreword remberg Academy with an increased num ber of events and activities at a peak level. Important anniversaries such as the 70th anniversary of the judgment of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in Tokyo and the 20th anniversary of the adoption of the Rome Statute have been reflected in the Academy’s work and activities. Major international conferences – as far as we can see the largest of their kind, dedicated to these important dates worldwide – were held in Nuremberg in May and in October. -

Nuremberg Icj Timeline 1474-1868

NUREMBERG ICJ TIMELINE 1474-1868 1474 Trial of Peter von Hagenbach In connection with offenses committed while governing ter- ritory in the Upper Alsace region on behalf of the Duke of 1625 Hugo Grotius Publishes On the Law of Burgundy, Peter von Hagenbach is tried and sentenced to death War and Peace by an ad hoc tribunal of twenty-eight judges representing differ- ent local polities. The crimes charged, including murder, mass Dutch jurist and philosopher Hugo Grotius, one of the principal rape and the planned extermination of the citizens of Breisach, founders of international law with such works as Mare Liberum are characterized by the prosecution as “trampling under foot (On the Freedom of the Seas), publishes De Jure Belli ac Pacis the laws of God and man.” Considered history’s first interna- (On the Law of War and Peace). Considered his masterpiece, tional war crimes trial, it is noted for rejecting the defense of the book elucidates and secularizes the topic of just war, includ- superior orders and introducing an embryonic version of crimes ing analysis of belligerent status, adequate grounds for initiating against humanity. war and procedures to be followed in the inception, conduct, and conclusion of war. 1758 Emerich de Vattel Lays Foundation for Formulating Crime of Aggression In his seminal treatise The Law of Nations, Swiss jurist Emerich de Vattel alludes to the great guilt of a sovereign who under- 1815 Declaration Relative to the Universal takes an “unjust war” because he is “chargeable with all the Abolition of the Slave Trade evils, all the horrors of the war: all the effusion of blood, the The first international instrument to condemn slavery, the desolation of families, the rapine, the acts of violence, the rav- Declaration Relative to the Universal Abolition of the Slave ages, the conflagrations, are his works and his crimes . -

1. Outline the Scope of the 'Nuremberg Principles'. What Is

NALSAR PROXIMATE EDUCATION NALSAR UNIVERSITY OF LAW, HYDERABAD P.G.DIPLOMA IN INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW 2012-13 PAPER IV – IMPLEMENTATION OF INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW Time: 3 hours Marks: 100 INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES 1. The questions must be interpreted as given and no clarification can be sought from the invigilator. 2. Students may be permitted to carry the bare text of the instruments and the codes. 3. Marks are indicated against each question. 4. Clearly indicate the Question numbers. 5. ANSWER ANY FIVE QUESTIONS including Question No. 8 1. Outline the scope of the ‘Nuremberg Principles’. What is their influence on the development of International Humanitarian Law relating to protection of Civilians during armed conflict? Specifically, examine their influence in the light of the Additional Protocols, 1977 to the Geneva Conventions, 1949. Substantiate your answer with suitable examples. (Marks 20) 2. Outline the importance of ‘Individual Criminal Responsibility’ in the implementation of International Humanitarian Law. How far the International Ad-hoc Criminal Tribunals have successfully resorted to this Principle in dealing with the Accused of Crimes against Humanity? Illustrate your answer with suitable examples. (Marks 20) 3. What is the role of the International Committee of Red Cross in the development of the International Humanitarian Law? Explain its role with reference to the development of safeguards to an accused during the Criminal Trial. (Marks 20) 4. What is the scope of protection to environment during armed conflict? How far, the provisions of IHL in association with the ENMOD Convention are adequate to safeguard the environment? Provide suitable illustration to support your answer. -

1. Examine the Impact of the 'Nuremberg Principles' on The

NALSAR PROXIMATE EDUCATION NALSAR UNIVERSITY OF LAW, HYDERABAD P.G.DIPLOMA IN INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW 2009-10 PAPER IV – Implementation of International Humanitarian Law Time: 2 hours and 30 minutes Marks: 75 INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES 1. The questions to be interpreted as given and no clarification can be sought from the invigilator 2. Students may be permitted to carry the bare text of the instruments and the codes. 3. All questions carry equal marks (15 marks each) 4. Clearly indicate the Question numbers ANSWER ANY FIVE QUESTIONS 1. Examine the impact of the ‘Nuremberg Principles’ on the development of IHL in the post Geneva Conventions phase. How far, the Nuremberg Principles have facilitated the implementation of the IHL? Substantiate your answer with suitable examples. 2. Examine the scope of ‘Individual Criminal Responsibility’ as an important principle of International humanitarian law. How far this principle has been invoked at the International Plane for the effective implementation of IHL? Support your answer with suitable examples. 3. Write Short Notes on any three of the following a. Importance of Marten’s Clause b. Principle of Complimentarity c. Protections to witnesses during criminal trial d. Scope of War Crimes in the Statute of International Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia e. Scope of Crimes against in the Statute of International Tribunal for Rwanda 4. Examine the scope of ‘Rape’ as interpreted by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda committed during the course of Non International Armed Conflict. Refer to leading case laws. 5. What is the role of the International Committee of Red Cross in the development of the International Humanitarian Law? Explain its role with reference to the development of safeguards to an accused during the Criminal Trial.